|

|

This is one of the most exciting teas we've ever shared with you, because many of you have probably never tried a Liu Bao tea. It is one of our favorite genres of tea, especially in the winter. Also, this tea is special because it was donated by our tea brother Henry Yiow, which means it connects all of you to our lineage of gongfu tea. Henry is one of Master Lin's oldest and brightest students. He is generous and kind, and provided this wonderful tea with an open heart. Through it, may you find the sentiment of heritage it expresses from us; and may it be a newfound love at first sip, promising many more amazing cups of Liu Bao in the future!

Before we start discussing Liu Bao, we must once again drive home the difference between red tea and black tea. What is called "black tea" in the West is actually red tea (hong cha). Red tea is oxidized completely during production, whereas black tea is characterized by post-production artificial fermentation. Its liquor is actually red - remember last month's tea, for example. Ordinarily, the mistake wouldn't be worth correcting, as it doesn't really matter what we call something. However, in this case calling red tea "black tea" is confusing, because there is another genre of tea called "black tea" in Chinese. So, if you call red tea "black tea" then what do you call the real black tea? The mistake began when Europeans first started trading with China and weren't allowed very far beyond the docks, learning most of what they knew about tea in broken Pidgin English from the dockside merchants. In those days, they also called oolong "black tea". (We know some of you are tired of hearing this, but repetition will help us correct the mistake, and there are many newcomers reading this as well.)

Liu Bao is a real black tea produced in Cangwu, Guangxi. The name "Liu Bao" literally translates to "Six Castles", which may refer to forts that existed in the area at some time in the distant past. The local mountains are full of canyons, streams and waterfalls that are misty year-round. The loose, fertile soil, humidity and proper sunshine make it an excellent region for growing tea. The tea trees here are neither big nor small leaf varietals, which we have discussed extensively in past issues. To briefly summarize: the origin tea trees are all what has become known as Camellia sinensis var. Assamica. They can grow bigger leaves, and generally have a single trunk with roots that grow more downward. As tea moved northward, naturally or carried by people, it evolved into a small leaf varietal, known as Camellia sinensis var. Sinensis. These trees can't grow as large of leaves, are more bush-like with many trunks and roots that grow more outwards. Liu Bao is a bigger leaf tea, but not as big as puerh. Neither is it as small as small leaf tea - you could say that Liu Bao is "medium leaf ", if you're willing to have a new category; otherwise, it's big leaf. Like puerh, the best quality Liu Bao tea is made from older tea trees.

Liu Bao tea is processed similar to shou puerh. In fact, when puerh manufacturers were developing the process of artificial fermentation used to create shou puerh in the 1960's and early 70's (officially licensed production began in 1973) they studied Liu Bao production, amongst other kinds of black tea. Ultimately, shou puerh production methodology is based on such teas, and owes its existence to them.

There are some variations in Liu Bao production, like all tea, so formulas can be a bit misleading, as they ignore the adaptations farmers make to suit the weather - different amounts of rainfall lead to different schedules and moisture content in the leaves, for example. Also, different factories/farmers have different recipes, even internally at different times or for variety.

Liu Bao was traditionally harvested in bud-sets of one bud and two leaves, though in modern times more leaves are sometimes picked to increase yield - a problematic trend in many tea-growing areas. There have been four general processing methods of Liu Bao tea throughout history. Though some scholars debate the dates and some of the details, we will present them as Master Lin taught us:

Since very ancient times, people in Guangxi have made very simple tea to drink. Long before tea looked like it does today, the villagers would cook the leaves in a wok with a tiny bit of water and then hang them up to dry from the rafters above their oven in the kitchen. The pinewood fires they cooked with would give the tea a smokey flavor. They would then boil this tea or serve it in bowls. Such tea is rare, but can still be found in some houses even today.

In the early days, before 1958, Liu Bao tea was steamed three times - once for de-enzyming (sa qing), then for piling and finally for compression. At that time, they didn't wither (oxidize) the tea. It was picked and directly sent to the "kill green (sa qing)" stage, which arrests oxidation and de-enzymes the tea, making it less bitter. In those days, the sa qing was done by steaming the tea as opposed to wok-firing, as with most teas. Then it was left overnight to be finished the next day. Master Lin thinks that leaving the tea over night is maybe how they discovered piling, and the improvement it makes on this kind of tea. The next day, they would roll the tea and steam it once more for piling. In some cases, cultures from previous batches would have been introduced to promote fermentation. It was then dried in big bamboo baskets over pine-wood fires, which is one of the defining characteristics of Liu Bao processing in all times. After that, the tea was once again steamed in order to compress it into the large baskets, as we will discuss in a bit.

After 1958, the farmers stopped using steam to de-enzyme the tea (sa qing) and started firing it in woks like other tea. They also stopped using steam to pile/ferment the tea. Instead, they began spraying the tea with water and piling it, like the way shou puerh is fermented. Consequently, Liu Bao went from being processed with three stages of steaming to just one, the final steam for compression. In the vintage era, Liu Bao was: picked, fired/de-enzymed, left overnight, rolled, sprayed and piled, dried over pine-wood fire, steamed and compressed.

In the 1980's there was another slight shift in Liu Bao production that was most likely influenced by the prominence of shou puerh: the piling process was extended longer and the piles themselves formed deeper to increase fermentation. This often gives the Liu Bao from this era a camphor flavor, as well as a wetter profile.

In the last ten to fifteen years, factories have also started producing green, sheng Liu Bao to rival sheng puerh. This tea is often harsh and strange, and it is difficult to know how it will age, if at all.

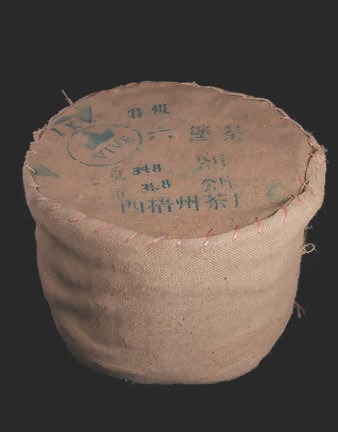

After fermentation (piling) and sorting, the leaves are steamed to re-moisten them and then pressed into large, bamboo baskets. The tea is packed down into these wicker baskets, pressed in tightly around the edges and more loosely in the middle, to facilitate the next phase of air-drying. The drying takes a few months, after which the tea is often aged.

In previous times, Liu Bao was only sold in large baskets weighing 40 to 50 kilograms. These large bundles were sometimes wrapped in huge bags for transportation, called "gunnies (Bao Lan 宝篮)" by Malaysian Chinese who spoke fluent English. In more recent times, Liu Bao has often been re-packaged after aging into smaller amounts. Modern Liu Bao is also produced in one-kilogram baskets, or into other amounts in boxes, bags, or even compressed into other shapes to hitch a ride on the bandwagon of puerh, as its neighbor has soared to great popularity and wealth.

When Liu Bao wasn't as famous, the baskets were aged for one to three years before even being sent to market. They were first put in air raid tunnels that are common in the area. These cool and moist wind tunnels were perfect for aging/fermenting the tea. After some period in the tunnels, the tea was then transported to wooden storage warehouses that had wet and dry rooms. They would be alternated between a drier space right after coming out of the moist tunnels, then to a wetter room. Drier spaces were often higher up, since humidity can differ a lot from the floor to the ceiling. This oscillation from wet to dry would continue until the masters felt the tea was fermented enough.

As we mentioned above, a lot of Liu Bao made these days is green and raw/sheng, so it doesn't have any piling or aging in the tunnels/ warehouses. And even the tea that is aged, is only done so for a very short time.

Traditionally, Liu Bao tea was exported to Cantonese tea drinkers in Malaysia and Hong Kong. In Malaysia, it was often served to tin/ pewter miners during their breaks. In mainstream Chinese culture in Malaysia, senior citizens refer to it simply as "big leaf (Da Ye)". It always had a reputation for being cheaper tea, often boiled, dried and re-boiled in restaurants. A lot of famous old Liu Bao teas have survived in Malaysia - mostly left over from the large stocks that the mines had when they closed. Some of the most famous, most coveted vintages of Liu Bao Tea are:

Master Lin ranks the five best Liu Bao teas in this order: 1930's Pu Tian Gong Qing, 1950's Zhong Cha, 1960's LLLL367 (which came from Hong Kong and has four "L's" as grades from one to four. The "L" represents "orchid" - "lan" in Chinese - because this tea is Orchid brand, and "four orchids" was their highest grade), 1950's Da Xing Hang, and finally 1950's Fu Hua.

It used to be that Liu Bao was a cheap alternative to aged puerh, often providing the same warming, deep and fragrant brews that settle the soul and aid in digestion. However, nowadays the more famous vintages of Liu Bao are also expensive. Aged Liu Bao is said to offer a dark red cup with mellow, thick liquor that tastes of betel nut. It is often regarded as the highest quality when covered with the spores of a certain yellow mold, which you will read about later on in this issue. In Traditional Chinese Medicine it is cooling or warming when needed, which is very unique, and also refreshing and good for dispelling dampness as well as detoxification.

Our tea of the month, "Old Grove", is a 2008 Liu Bao. It was aged by Henry in Malaysia, the most famous and best place to age Liu Bao tea. It is deep, dark and mellow and settles the soul. Our tea was produced in the traditional way, including one to three years aging in tunnels and warehouses, which makes it actually a slightly older tea.

Since Liu Bao is a black tea, characterized by post-production fermentation, storage plays a huge role in developing the character of the tea. When you drink a black tea, you are always drinking its storage as well. This tea was stored in Malaysia since 2008, which means it also carries a bit of the magic, history and heritage of our teachers there.

Liu Bao is one of our favorite teas, combining the power of big leaf, old-growth trees with the processing of man, the fermentation of Nature and the work of all the microorganisms that change the tea so magically over time. The Qi is deep and Yin, moving towards the center, carrying you inward as you drink. We hope it keeps you warm and brings joy to you and your loved ones this holiday season!

We opened A basket of history, Kept by a friend In some forgotten corner Of a world moved on. The treasure inside opened the years; Sipping Time Wobbled sideways And fell over the brink Of the Timeless...

Try brewing this tea gongfu if you can. Liu Bao is much better when prepared in this way. If you do not have a gongfu set, go with a side-handle pot or a teapot, as this tea may not be that nice directly in the bowl since many of the leaves are small from the compression and subsequent breaking up of the tea.

Like shou puerh or aged puerh, aged Liu Bao is often better when it is a bit darker. Try adding a bit more leaf than you are used to, or steep the tea a bit longer. You want the liquor to be dark red or even black (like the name of the genre). When the steam swirls around the dark liquor, with shades that fade from black to browns, and then into maroons and reds with a gold ring around the edge, you will know you have got the perfect cup of aged tea. We have given you enough tea to have one very strong session or two moderate ones. It will be up to you to decide what the occasion calls for.

Liu Bao tea needs a higher temperature, as with all darker teas: aged or roasted oolongs, shou or aged puerh. The ideal is, of course, charcoal, but make sure your water is at a higher temperature no matter what kind of heat source you are using.

For this month, practice pouring the water into the teapot faster and with a greater force. Aged puerh or Liu Bao will be better this way. The quicker you fill up the pot the better. Also, make sure you shower the pot both before and after steeping in order to preserve the heat. These two steps will have great impact on the quality of the final cup.

This month's tea is very "patient", which means that you can get many steepings from it. Preserving the temperature in this way helps to make any tea more patient. Teas that are kept at a constant temperature release their essence slowly over time, allowing them to last longer. They are also steadier and more pleasant this way.