|

|

Right before the solar term, guyu,1 new tea buds, each but one leaf alone, are plucked to be ground into powder. They are then pressed to remove the moisture inside, ground into powder and finally pressed into round cakes. Some people dry tea leaves with other herbs that overpower their essential aroma and flavor. In general, tea that tastes light and sweet, with a fine, long-lasting aftertaste that awakens the Qi is the best kind of tea. The Bamboo Shoot tea from Mount Meng of Shandong Province is so unique that it is Heavenly.2 Even though tea is essential in life, due to its coolness,3 it is not recommended for people with certain aliments to drink too much tea.4

It is best to pick the young buds on a warm, dry day, storing them in a similar climate rather than a cold and humid place. The leaves are placed on a wooden rack with fire burning below to slowly roast them dry. Roast the tea every two or three days5 to keep the leaves at body temperature and humidity won't corrupt the tea. If the fire is too harsh, then the leaves will be burned. The tea leaves that are not being roasted should be sealed in an envelope and placed in a high place. If the flavor and taste became stale after some time, then boil them, rather than whisking or steeping, to improve the flavor. To create a tea with Heavenly Fragrance, one shall collect the petals of a newly-blossomed osmanthus.6 It is crucial that one only gathers these precious blossoms during a sunny noontide, so they will not overcome the fragrance of the tea.

Before whisking tea, one should warm the bowls first.8 If the bowls are cool, then the tea will sink to the bottom. If there is not sufficient tea, then the white froth will not rise. The more tea there is, the easier it is for a white cream to ascend. Put one scoop of tea into the tea bowl and then pour a little hot water to dissolve the powder. Immediately after the powder is dissolved, add an adequate amount of hot water, filling the bowl in two of three thirds while whisking the liquor in graceful circular motions. A bowl that shows no mark where the water was is the best. People nowadays like to trade the fragrance of tea for that of flowers;9 among them plum blossoms, osmanthus and jasmine are the best. Put several flowers into tea cups and cover them immediately with hot water. In a matter of seconds, the dried flowers will blossom inside of the cup, opening to the heat and moisture, and one will smell the floral perfume long before the cup touches one's lips.

Any kind of fragrant flowers is suitable to make scented tea, the best of which exudes but a hint of some favorable aroma. Pick the flowers when they are in bloom. Make a two-tiered bamboo lantern and place the flowers into the lower section while the tea leaves rest on the upper section. Seal the lantern tightly and let it sit overnight. On the following day, open the lantern and replenish the bottom with freshly-picked flowers. Repeat this procedure for several days, until the tea leaves absorb the lovely fragrance of the flowers. It is also possible to employ this technique with borneol instead of flowers.10

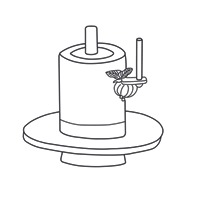

The cauldrons for making tea are the same as those used by Daoist alchemists. The size of them is seven cun high and four cun in diameter, with three-cun-high feet and a one-cun opening for air flow.11 The inside of the cauldron is gilded with copper, which is extremely rare nowadays. Mine is a ceramic crucible inlaid with silver, which is even better. The height of the handle rungs is seventeen-and-a-half-cun, with woven rattan handles. There are hooks along the sides to hang utensils such as an ash brush, ladles, a sieve for water and a bellows.

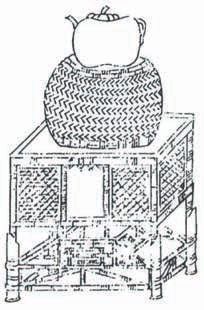

In antiquity, stoves of this construction did not exist. I installed mine in the forest. Because it is earthenware, it looks like a stove for cooking, except the top is one-and-a-half-chi high, with another layer above, which is nine cun high, one-and-a-half-chi long and one chi wide.12 I've decorated it with poems and odes to Tea. There are two vents on the lower part for adding coal or wood and the stove has two round openings to place water kettles. I positioned a fair-sized rock in the front as a seat for the tea master. I've found an eccentric octogenarian, a man without a name, who is childlike and simpleminded like a child. I have no idea where he is from, either. His attire is also otherworldly, in that he wears crane robes13 closed with a hemp belt and a pair of straw shoes. He is slightly hunched by age and his face is covered with countless wrinkles, even onto his neck. He has a pair of topknots on his head. Overall, he is shaped like the character for "chrysanthemum," so I've come to call him "Elder Mums."14 Each time he prepares tea at this stove, his purity multiplies the virtues of the tea.15

It is best to use qingmeng stone,16 as it breaks up phlegm that builds up in the lungs and throat according to Chinese medicine. Other materials are not as beneficial to the tea leaves.

Traditionally, tea grinders are made of gold, silver, copper or iron. All of these are prone to corruption,17 so I favor qingmeng stone.

The sieve for tea is made out of gauze and is five cun in diameter.18 If the gaps in the gauze are too small, then not enough tea powder will pass through the sieve. On the other hand, if the holes are too large, then the sieve won't sift out unfavorable impurities.

Most people use wooden racks with intricate and complicated decorations - not me. I use spotted bamboo or purple bamboo, which is the loftiest material for making a rack.

Since the purpose of spoon is stirring, it needs to be powerful. In antiquity, people favored golden spoons, though there are many silver and bronze ones nowadays. Bamboo spoons are lightweight. I once had a spoon made of a coconut shell, and it is my favorite. After I had the coconut shell spoon made, I met a man who was blind in both eyes. Amazingly, he made hundreds of bamboo spoons of exactly the same size. Bamboo is suitable for making spoons that are different from the ordinary ones. Even though gold is very expensive, it is not any better than a bamboo spoon.

The whisk is made out of bamboo, and those from southern places such as Guangdong and Jiangxi provinces are the best quality. The whisk is usually about five cun19 long. After scooping some tea powder into the bowl and then adding hot water, it is time to start whisking. When the white froth starts to form in clouds, a heavy rain falls in trails. Then it is time to stop whisking.

Traditionally, people used tea bowls from Jian'an.20 Those that are decorated with fine pine needles or rabbit's fur are the most sought-after. Nowadays, tea bowls from the Gan Kiln21 look like those from Jian'an. However, after hot water is poured into the bowls, the hue of the tea liquor as viewed in Gan ware is not as bright as that in Jian ware. I prefer Rao ceramics,22 which offer a gorgeous, pale celadon color when the tea liquor is in them.

When the kettle is small, the time spent waiting for the water to boil is shorter. Furthermore, smaller kettles are easier to maneuver when pouring into tea bowls. Traditionally, kettles are made of iron and are called "ying."23 During the Song Dynasty, people shied away from iron to avoid the inevitable rust in favor of ewers made of gold or pure silver. My kettle is ceramic and is five cun high with a two-cun neck and a seven-cun spout.24 It is important to boil the water to the perfect point. If the water is not brought to such a boiling point, then a layer of dregs will float on the surface of the tea liquor. On the other hand, if the water is over-boiled, the tea will sink to the bottom of the bowl.

It is crucial to boil one's water with flaming coal, which is termed "live fire," so that the water will not be heated in vain. In the beginning, the bubbles appear haphazardly like fish eyes. Then, more air emerges, and the bubbles are like spring water or a string of pearls. At the last stage, the bubbles grow larger and the water boils violently like the high tide. At this point, all the vapor in the water vanishes into the air. This is the so-called "three boiling" method that can only be achieved with lively, flaming coals.

The tea immortal Qu25 ranks water sources for tea as follows: the Qi spring at the Elder's Village in Qingcheng Mountain26 is the best, Eight Virtue Water from Mt. Zhong27 is the second best, Vermilion Pond at Red Cliff28 is the third best, while the water from Bamboo Root Spring29 is the fourth best. Others might conclude that the water from mountains is superior to that from a river, which is in turn superior to the water from wells. However, Bochu30 commented that the water from the middle of the Yangtze River is the best, while the Stone Spring at Hui Mountain31 ranks second. He claims that the Stone Spring at Tiger Hill32 is the third best, while the Danyang Well33 is the fourth. Daming Well34 is the fifth, Song River35 is the sixth and Hui River36 is the seventh. Others might argue that the water from Kangwang Cave on Mount Lu37 is the best and the Stone Spring at Hui Mountain38 is the second best. The water from under the rocks at Lan Brook in Qizhou39 is the third best and the water from the Lower Caves at Shanzixia, Xiazhou40 is the fourth best. The water from Tiger Hill in Suzhou is the fifth best and the Stone Bridge Pond on Mount Lu is the sixth best. The cold water from the middle of the Yangtze River ranks the seventh best while the Xishan waterfall at Hongzhou41 is the eighth best. The water from upstream of the Hui River, at Botong Mountain in Tangzhou,42 is the ninth best and the water from Dingtiandi on Mount Lu is the tenth best. The water from Danyang Well in Runzhou is the eleventh best and the water from Daming Well in Yangzhou ranks the twelfth. The cold water from upstream of the Han River43 in Jinzhou is the thirteenth and the water from Fragrance Brook at Yuxu Cave in Guizhou44 is the fourteenth. The water from West Valley, Wuguan at Shangzhou45 is the fifteenth and the Song River in Suzhou is the sixteenth. The waterfall in the southwestern slope of Tiantai Mountain46 is seventeenth, while the Yuan Spring at Chenzhou47 is the eighteenth. The tributary water of the Yanling area of the Tonglu River48 in Yanzhou is the nineteenth while the snow-melted river water there ranks twentieth.49