|

|

Long ago, in the days before the art of tea, before people shared it as hospitality in homes throughout the kingdom, it was a medicine to aboriginal shamans and healers, who used its leaves to foster meditation and to connect with Nature's guidance and wisdom. In those lost days, when the sky was clear and Nature wasn't a place people went to if they had an interest in the "outdoors," but rather was life itself, tea was all simple, wild and pure. Undomesticated trees deep in the forest were sought and harvested according to the life cycle of the tree, and with a reverence expressed in prayers and offerings of thanks to the wise old trees for their gifts. There was no processing to speak of: the tea was plucked and dried, carried in bundles amongst other healing herbs.

The preparation of tea was also very simple in those ancient times before we measured time - when Nature measured it for us in the moons and seasons that followed her. Leaves were simply withered and dried, and then steeped in bowls or boiled in cauldrons and ladled into bowls of warmth. The tribes used tea to welcome guests, though the rest of the kingdom was millennia away from knowing the joys of the Leaf. But they did so sparingly, as the old trees were precious, hard to find, deep in the mountains and didn't produce but a handful of leaves when She saw fit - when a worthy shaman made offerings. All of the origin stories of tea in aboriginal cultures pay tribute to this distant time in the past, as do the altars beneath old trees, which even today hold similar prayers.

The Ku Chong tell a story of lost hunters who elected one of their number to climb a foreign tree and see if he could find his bearings. They were worried about an approaching storm and being stranded in the jungle. When the brave climbed the old tree, he saw a sea of green stretching to the ominous, stormy sky. He still had no idea where he was. Then he noticed the strange, fairy-like tree once more and casually plucked a leaf to chew on. As soon as the powerful juices that had flowed down from the sky and mountains through the Earth and roots came into his veins, he saw clearly the road home.

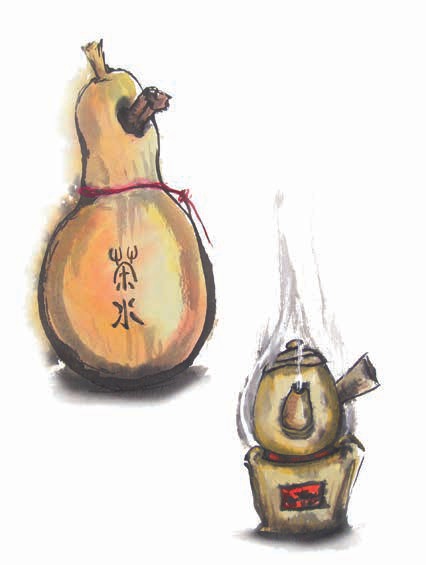

Imagine, if you can, sitting in the chorus of a pristine jungle, sharing bowls of the brightest tea you have ever tasted, boiled in clear and clean spring water, and shared among people who love you, who would die for you - people who were you, and you them. Imagine the old shaman's hands as he scoops ladles full of the rich liquor with a pierced gourd attached to bamboo, the thin end of the spout now caked brown with years of boiled tea. The liquor is earthy, astringent and bitter, but it is also sweet, very sweet - a sweetness that lasts long on the breath and reminds you of the love of the one sitting next to you. As you sip, bowl by bowl, the silence becomes noisier: the birdsong clearer and the cicadas a rhythm that resonates in your chest. You begin to understand the trees and birds, wind and sky. It talks to you of your road home. It shows you visions that answer the tribe's worries. And the old shaman grins, his weathered face now as jungly as the trees, for he knows that look on your face all too well. He knows the road home.

I recently watched an old interview in which Jerry Garcia said, "Music is holy, and the business and industry we have built up around it can prevent music from doing what it was intended to do." That approach to music is why I am a fan of his, and I think that what he said is just as true of tea, if you restate it using the word "tea" instead of "music." Sometimes, I feel compelled to defend a more spiritual approach to tea, as if the thousands of years that people have used tea to cultivate themselves never happened. Alas, I am not opposed to some simple kitchen tea drinking, welcoming guests and enjoying the hobbyist aspects of tea. But tea is much more than that, and you cannot approach Her depths with the intellect alone.

There is a story about a botanist who travels to the jungles of South America. He hires a local guide to show him through the forest. As they walk, the young man points out all the local plants, naming them to the botanist. After an hour of this, the botanist exclaims, "Wow! You know a lot about plants. You've named every one we have passed!" The young boy looks down at his feet, ashamed. "No, actually I have so much more to learn. I mean, I do know their names, but I haven't yet learned their songs." This story can teach us a lot about tea and teaware. There are a lot of people who know the names of teas, but I, personally, will always be more interested in their songs...

Traditional Chinese Medicine is among the oldest and most refined healing modalities on earth. The ancients developed comprehensive systems of understanding human health and longevity that are unrivaled. They accumulated a vast library of herbal remedies and learned to use needles to move the body's energy for healing. Their concept of health transcended mere physical well-being to include the mind and spirit in harmony with an equally deep cosmology. They were more shamans than doctors.

The early Daoist sages, who form the now-legendary beginning of Chinese medicine, saw health in terms of physical well-being and longevity, mental serenity and spiritual cultivation towards a harmony with Nature and the cosmos. They were mystics. Their great body of herbal lore was accumulated over centuries, handed down from the tribal peoples who preceded them. They refined this nature wisdom, finding more herbs and learning how to prepare them better. They did this through trial and error, innovation and exploration, as well as honing their spirit to Nature, and using insight to guide them towards the herbs that aid in human fulfillment - holistic success, in terms of one system of body, mind and spirit.

Shennong, the father of Chinese medicine, is said to have exclaimed that tea was "the king of all medicinal herbs (藥中之王)," for tea was certainly amongst the herbal tonics of these ancient "Cloudwalkers," called thus because they wandered the mountains and mists above the valley cities below. My favorite poem highlights the lifestyle of these early sages:

I asked the boy beneath the pines. He said, "The master's gone alone, Herb-picking somewhere on the mount, Cloud-hidden, whereabouts unknown."

Until the modern age, Chinese doctors were supposed to be much more than just healers: They often were martial arts masters, artists and calligraphers, well read in the classics and sages in their own right, who had meditated and self-cultivated to a high degree. The best doctors could diagnose just by seeing a patient. And it is a well-known fact, even now, that the Qi of the one placing a needle is as important as finding the right location to place it. This is, of course, akin to tea, as the brewer is the most important element in a session. Even modern master TCM doctors, like Zheng Man Qing (鄭曼青), were well known to be talented in all these fields. He was a renowned calligrapher and painter, one of the best tai chi teachers of the modern era, an excellent Chajin and one of the founders of the modern Traditional Medicine Association in Taiwan and China, influencing all these fields around the globe. His commentary on the Dao De Jing and other classics also proves that he was not only incredibly learned as a scholar, but had a deep and penetrating eye, which only comes from years of self-cultivation.

It is in this lost lore of myth and legend, where sages bigger than life cloudwalk, that we must start our journey towards understanding the sidehandle pot. Though lost in legend, beyond what history's lens can resolve, we must use some poetry and mythic imagery, as we have done here, since most of the journey of sidehandle pots, historical or otherwise, is surrounded by spiritual aspirants and religious lore. After the "ding (鼎)," which was essentially a cauldron, it became popular to boil herbs on smaller stoves with a sidehandle pot. The beginnings of this humble vessel are shrouded beyond our reach, but one might assume that this began as a way for solitary hermits to make smaller batches of herbs for their own experimentation and consumption. The sages knew that fire is the teacher of herbs, as it is of tea. It is heat that draws the essence from the plant, and heat that moves that same medicine through the channels of our bodies. Powders and raw herbs did exist back in ancient times, but were rarely used. If you have ever taken boiled Chinese herbs, you will know how much more efficacious such a brew is than capsules, powders or tinctures - much like whole food is better for us.

Sages used herbs on a daily basis. Not all herbs were remedies for ailments. Many, like tea, were spiritual herbs, meant to harmonize the energy they call "shen (神)," which is the cosmic, Heavenly energy that connects us to Nature, and ultimately, to the stars. Tea is one such shen tonic that can be used every day to promote meditation, relaxation and overall well-being, and unlock insights necessary in spiritual growth. One of the first Chinese materia medica to mention tea said that it was "to brighten the eyes (明目)." In Chinese wisdom, it is said that when the cosmic energy, the shen, descends to the heart, the eyes light up - which is why Buddhist and Daoist sages were typically depicted with glowing eyes. Meditation and Qigong could also help one achieve this, but so can herbs like tea. Many of us, no doubt, have experienced the illumination of the heart and eyes through a powerful tea session.

Small clay stoves and sidehandle pots conserve wood and/or charcoal and could be made easily in small sizes that were suitable to a hermitic life, allowing the monk to boil just the amount of herbs he needed. At some point, these vessels became more popular than cauldrons, especially in areas where clay was readily available and such vessels easily made. These small stoves and sidehandle pots were made with handles that jut up at an angle, to prevent the handle from getting too hot. Decanting the boiled herbs in this way is also easier to use than a cauldron, as it is much easier to get the last of the boiled tonic out, as opposed to using a ladle with a cauldron. Maybe they also liked the way the clay would absorb the herbs over time, becoming seasoned and glowing with its own power. Though we don't know all the reasons why sidehandle stove and pot sets came into vogue amongst sages, we can trace the roots of the sidehandle pot back to these ancient sages and their herbal brews. And we can be certain that some sessions, especially near Yunnan and Sichuan, involved the boiling of tea leaves as one of the prominent herbs they used towards longevity and self-cultivation. I often portray such sessions in my artwork.

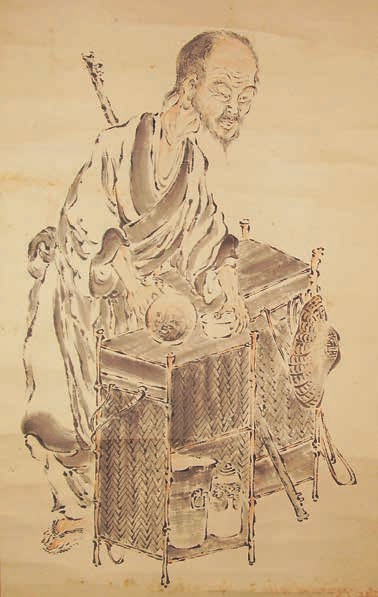

Baisao is a hero to our tradition, and a shining constellation in the sky of tea sages who inform all Chajin throughout the ages. "Baisao (老賣茶翁)" literally means the "old tea-seller." Baisao lived from 1675 to 1763, in the Edo era of Japan. He was ordained at the early age of nine, practicing earnestly in meditation. He was recognized for his devotion and wisdom by his teacher, Kerin Doryo, early on. Baisao traveled extensively starting in 1696, studying under several teachers and exploring many scriptures. His teacher asked him to be abbot of the Ryushinji, an Obaku temple. He declined the offer, instead stewarding the temple until Daicho Genko became abbot in 1724. Baisao felt that the Buddhist temples of the time had lost their way, cultivating relations with wealthy patrons to build and maintain temples, rather than creating monasteries that were genuine refuges for those seeking spaces of self-cultivation.

The English word "Zen" is derived from Japanese, which was a transliteration of the Chinese word "Chan (禪)," which is pronounced "Tsan" in the South, where many of the early Japanese monks who traveled to China went to study and bring Buddhism back to Japan. To introduce the essence of Zen and why Baisao left his order, however, we have to trace the etymology back one more step, for "Chan" is also a transliteration of the Sanskrit word "dhyana." "Dhyana" is a profound word, with many and vast meanings, but in its simplest form, it means the "meditative mind," the mind cultivated in a meditation practice, in other words. Consequently, Zen is meditation. It is a mind, a way of seeing. And since its birth, Zen has sought to transmit this mind from teacher to student, understanding that the method is not as important as the seeing. This is in concordance with the Buddha's teachings as well, since he often compared his method of practice to a raft, suggesting that once one had reached the other shore, the raft would no longer be needed. "Buddhism," we must remember, is a Western word, and very modern compared to the thousands of years Buddhist practices have survived. Zen is a mind, a way of seeing, and one that must be transmitted and cultivated.

Baisao "saw," penetrating the Zen mind to "see things as they are," which is called "kensho" in Japanese. He saw that the current temple life was not conducive to the transmission of a pure Zen, as he saw it, and decided to disrobe - but not to become a layperson, but rather to live a life that he felt was in greater harmony with the teachings of Zen. Out of time and place, with deep insight into ancient Chinese Daoist hermits that he could not have plumbed through literature, he donned the black-and-white robes of an ancient Cloudwalker. He moved to Kyoto and set up a small stall by the side of the road, offering bowls of tea for donations. At that time, selling such bowl tea was amongst the simplest, low-class jobs available, which suited the humble monk well.

Baisao had spent most of his life in Nagasaki, which was at that time the only port open to Chinese trade and even had a small Chinese community. Probably through the temple, Baisao had made some Chinese connections, granting him access to Chinese teas, including some Wuyi Cliff Tea. This made his tea very special. Prepared with a cultivated mind, and like all great tea, poured from a heart of stillness, Baisao offered his teas to passersby. Unlike the other vendors, he didn't charge a penny for a bowl, but offered it freely, leaving out a donation box for grateful patrons. This meant he often went hungry, writing of how he was saved from starvation one winter by an old friend who visited with food. But he suffered for his art, for his tea.

Where he learned of the ancient Daoist ways, we don't know. Perhaps he did catch glimpses of them in the classics or in poems, but no matter where his introduction came from, he penetrated the depths through tea - a practice we try to continue today. He commissioned local friends to make him teaware that captured the essence of the tea he prepared, echoing the great Daoist sages who brewed herbs in the mountains. Of course, this means he used a sidehandle pot and stove to boil his tea. It is likely that he also steeped tea as well, as some of the teas he served, especially the rarer Chinese ones, would have been much better prepared in this way.

Over decades, Baisao started attracting students who, with keen eyes that also "saw," realized that this simple, scraggly-haired old man was actually quite wise. They started assembling as much for the teachings as for the powerful brews he served. In one of his poems, he cheekily suggests that the great tea sage Lu Tong needed "Seven Bowls," referencing Lu Tong's famous poem, while Baisao himself only needed the one to stir enlightenment in the drinker. By the time he passed away at the ripe old age of eighty-eight, Baisao had quite the following. He had seen the way practitioners of the whisked tea ceremony, called "Chanoyu," copied and revered their tea saint, Rikyu, and in typical Zen-rascallyness decided that this would betray the humble spirit of tea and Zen, so he burned his teaware before dying so others would find their own way. But Zen and history have a sense of humor, and his students had already copied most of his poems, which thankfully still exist, as well as drawings of all his teaware.

Some time after Baisao joined the tea steeping in the sky, many Japanese Chajin started to become resistant to all the formality of the whisked tea ceremony. They felt that practitioners of Chanoyu were too strict and tight in their tea preparation, and too fussy over expensive teaware, which they felt betrayed the essence and spirit of tea. Without a doubt, these stereotypes were partly unfounded, as there were most certainly great Chajin amongst those practicing whisked tea. These new Chajin used Baisao as their saint and started practicing a new form of tea ceremony called "Senchado." They retreated to the mountains, building simple hermitages and living lives with nostalgia for the ancient Daoist Cloudwalkers they admired. They wrote poems, painted, practiced calligraphy, meditation, and sometimes, martial arts. They meditated and sought to commune with Nature, as all Chajin try. This wistfulness for lost times in a mythical and ancient Dao of the mountains of China was encouraged by tea. Tea has always inspired the heart to turn towards myth: to the timeless place where "clouds and mist" and "temple bell mind" are adumbrated by the passing of a dragon through the overhead clouds. These sentiments continue today - tea still inspires us to look beyond the mundane.

The practitioners of Senchado all designed teaware based on drawings of Baisao's teaware. The word "sencha" actually literally means "simmered tea." Though we steep sencha nowadays, it was more often boiled at that time. (This is something worth trying. You may be surprised by how great it is, when simmered at low temperatures with a bit of care and attention.) These tea sages saw tea as a kind of alchemy, through which the practitioner harmonized the elements within and without. And so, once again, the sidehandle kettles and stoves thrived, inspiring ceramicists in Japan to make all new styles, mostly designed to be simple, rustic and "wabi." The sidehandle crossed the sea, and continued its journey through many mountain sessions and roadside enlightenments.

Set up the tea hut On the bank of the Kamo River. Passersby idly sit down, Forgetting host and guest, And drink a bowl of tea, Ending their long slumber. Awakened, they now realize They're the same as before.

The sidehandle pot was traversing a different evolution in China. Sometime after it had crossed the sea to Japan, gongfu tea was born in southern China. "Gongfu (功夫)" literally means "mastery through self-discipline," and refers to any art or craft that can be mastered with focus and practice as a way of life, including martial arts, which is what the word is more often associated with in the West. Though "gongfu tea (功夫茶)" has become a generic term in the last few decades, coming to mean any style of brewing anywhere in Asia (so long as Chinese people are making tea, they call it "gongfu tea"), this brewing style began as a local method in Chaozhou.

Gongfu tea was created in the early Qing Dynasty (1644 - 1911) by martial artists. They sought to embody their practice - living and breathing the teachings they aspired to become. They made tea the way they lived: in harmony with the grace and flow of the "Watercourse Way (水道方式)." This means preparing the tea in the way it wants to be prepared. They saw tea as a vehicle to self-cultivation, practicing graceful movements and careful attention to the tea, so as to bring out the best in each cup.

Gongfu tea, like all human action, was also, in part, economically motivated. At that time, most people in China brewed tea in large pots, with large cups, steeped for long periods, while they meditated or chatted. This is when the West started a tea trade with China, which is why Western people also started preparing tea in this way, which continues in the West even today. But larger teaware and more leaves is also more expensive, and to the Southern martial artists, wasteful. Martial arts are often formed on a philosophy of frugality - conservation of energy. The ideal is to dodge, and not be where the opponent strikes. Second best is to deflect, using the opponent's own force and momentum against them. A distant last is to block, harming oneself in the process. (These are deep life lessons for dealing with challenges as well!) In his epic Tea Sutra, which we translated for the September 2015 issue, Lu Yu also said "the essence of tea is frugality." The creators of gongfu tea wished to use fewer leaves in small pots and cups to conserve money, time and energy.

Gongfu tea was also born because oolong tea was born at the same time, also in the South. Gongfu tea traditions and oolong tea grew up together, fitting hand in glove. This powerful, semi-oxidized tea was perfect for drinking in small cups, which encourage smaller sips. Oolong enters the subtle body through and over the head, unlike darker teas like puerh or black tea, which enter the Qi through the stomach and chest. Smaller sips encourage a greater dispersion of the wonderful fragrance of such teas, as well as more movement in the Qi. (Try experimenting with as small of sips as you can possibly take, seeing how this affects your oolong tea. Smaller cups demand small sips and are, therefore, ideal for this.)

These early gongfu tea creators used sidehandle pots and stoves to bowl their water. These sets are one of the "Four Treasures" of gongfu tea, along with porcelain cups, Yixing pots and a "tea boat (茶船)." The sidehandle pots were in keeping with their own Daoist sentiments, hearkening back to the Cloudwalkers and their herbs, whom they, like the Japanese who practiced Senchado, also greatly admired. But all aspects of gongfu tea are spiritual and practical, as improving the tea is always paramount. These Chajin also used small sidehandle pots and stoves because they made better tea. The early gongfu tea men realized that overboiled water discourages the fragrance and Qi of the tea from rising. As the water boils, it breaks up and loses its structure. This is especially important if one has hiked kilometers into the mountains to gather precious spring water from famed locals, as tea lovers then and nowadays are wont to do. Small sidehandle kettles allowed them to boil one or two steepings at a time, so that the water was always fresh and always at the perfect temperature - and heat is principle in gongfu tea.

In this way, sidehandle pots had found their way from the boiled herbs of Daoist sages to the new nostalgic traditions of Japan based on Baisao, and then down a separate road to the gongfu tea of martial artists in the south of China, finding a home in all these teas for unique reasons, but always based on its simple, rustic roots amongst the literal roots these pots had boiled in the mountains, literal and mythic, of ancient China.

For most of the few centuries that the Japanese practiced Senchado, they actually boiled tea. At some point in that journey, however, the influence of Chinese steeped tea started to change them (starting with the seeds Baisao had planted, as he also steeped some Chinese tea), and they more and more started steeping their tea. Influenced by gongfu tea, many practitioners in Japan started using Yixing teaware, which was extremely precious in Japan due to high customs tariffs on imported goods. They started using cooler temperatures to steep their greener and greener teas, often using two Yixing pots: one as the teapot and one as the "yuzamashi," which was used to cool water before steeping and then (sometimes) acted as a pitcher to decant the tea liquor.

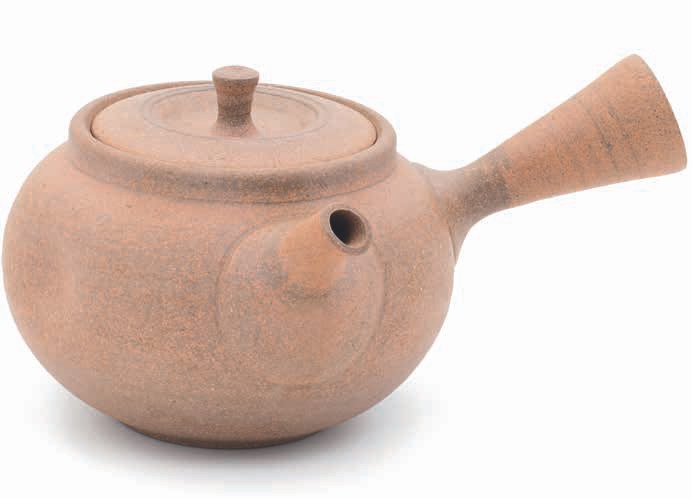

As these new brewing methods became popular, the sidehandle pot did not vanish. After all, not everyone could afford to use imported Yixingware. At some unknown time, sidehandle pots started to move from stoves to boil water or tea to actual vessels for brewing, and the "kyusu" was born in Japan. Up until the Second Great War, Japanese kyusu were mostly designed in the same fashion as all sidehandle pots had been for centuries: with an upward-flared handle, not abutting the spout, but not at a right angle either - somewhere in between. They were often small and dainty, and a shortened handle was favored so that it could be held against the palm or deftly between two fingers. However, as the art of steeping green tea evolved, so did the kyusu. Over time, craftsmen and Chajin working together innovated the pots to be flat and open so that they would not preserve heat and steam/cook the tea in between steepings. They also began moving the handle more towards a right angle to the spout and pointing directly and straight out, as opposed to up at an angle that hearkens to the days when these pots sat on stoves and the angle helped prevent the handle from getting hot. Then, slowly, sieves in the spout were invented - with more and finer holes than any other teapot in the world - to block the needle-like leaves of sencha. (As you may remember, tea leaves got smaller and smaller as the trees moved north, naturally or carried by people, resulting in the very small leaves in Japan, which are a response to the cold weather.)

Thus, trough the innovations in tea production and preparation that were happening in Japan in the later half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, sidehandle pots took the third of the four roads we will discuss in this introduction, becoming the world of kyusu - a flourishing art that continues today. There are still powerful traditions of preparing sencha in kyusu, as well as ceramicists in Japan who are creating beautiful examples of this teaware. The Tokoname region of Japan is the most famed for its tradition of making kyusu, dating back centuries when they were still used for boiling tea and water for tea. A study of those traditions would be very worthwhile, and though too far afield from this introduction, which is, of course, winding its way to my own tradition, kyusu and Senchado are both topics we hope to cover in future issues of Global Tea Hut.

The road to our own bowl tea ceremony invariably leads through Taiwan. As we have discussed before, Japan controlled Taiwan from 1895 to 1945, and though the Taiwanese don't always like to admit it, Japanese culture has impacted Taiwanese culture and aesthetic, and continues to do so even now. It is evident in the art, architecture, flower arranging, teaware and tea brewing of Taiwan. But the synthesis of Taiwanese art and aesthetic with Japanese is by no means a mere copy - the Taiwanese are incredibly creative people and have, over time, innovated their own cultural blend of traditional Chinese, Japanese and even Western culture (probably listed in that order of influence).

In the 1970s, Taiwan passed through a great economic boom. I can remember longing to visit Taiwan as a child (even finding it on maps) because all my Star Wars figurines and ships said "Made in Taiwan" on the bottom (the way everything is "Made in China" nowadays). In April of 2016, we translated the Emperor Song Huizhong's Treatise on Tea. In the introduction, he highlights that the flourishing of arts, like tea, was in large part due to the peace and prosperity of the Song government (a peace which sadly didn't last, as the dynasty ended during his reign). There is truth in this, since people focused on the basics of life, like food and shelter, don't have the time or energy to focus on art and culture. Once Taiwan began to grow and develop in every way, the arts and culture there also flourished. Of course, tea and tea arts surfed the crest of this wave, making Taiwan, for a time, the tea culture capital of the world. Teahouses grew like new buds on a spring field after the rains, new books and magazines were published and the modern scholarship of tea, including topics like puerh and Yixingware, was born (directly influencing the creation of this magazine in your hands).

For some time, Yixingware dominated the Taiwanese tea world. Modern teapot makers in Yixing remember the times when literally all of their pots were sent to Taiwan. There were even many Taiwanese potters who imported ore and clay from Yixing, to learn the craft, like Luo Shi (羅石), whom we shall discuss later in this issue. Some of this craft still continues, though most of these potters have since discovered local Taiwanese clays that they can blend with various powders to create Yixing-like colors. As we discussed in the September Extended Edition, this same trend has affected Yixing itself, since the mines were closed in the late nineties and the ore/clay has become scarcer and more expensive.

At some point in the growth of tea culture in Taiwan, local potters began to turn their attention more and more to the growing market for teaware. A new age of uniquely Taiwanese teaware was born. Many of these potters came from other backgrounds, attracted by the flourishing demand for unique teaware that had a Taiwanese flare, as opposed to the Yixing market, which had bubbled to beyond what many could afford and then popped in the late eighties, costing many shop owners who couldn't adapt to other tea and teaware their livelihoods. In the vacuum left behind by the hundreds of Yixingware shops that closed after the market collapsed stepped local Taiwanese potters with new designs and ideas.

Looking to set themselves apart from the many potters creating teaware, many ceramicists started redeveloping classical pottery and glazing techniques like celadon and "tian mu (天目)," and, of course, the Japanese influence shone throughout this development. These new kinds of teaware started to have an impact on Taiwanese tea brewing styles as well, as Chajin and ceramicists worked together to create many new and innovative ways to prepare tea, as well as to create new teaware that facilitated the evolving Taiwanese aesthetic.

At some point in the late nineties or early part of this millennium, some Taiwanese potters started making sidehandle pots that were modeled after the kyusu, but also distinctly Taiwanese. A return to natural, simple and rustic teaware was becoming popular in Taiwan, as was a growing influence from traditional Japanese tea culture, including tetsubin (cast iron) and ginbin (silver) kettles and the art of making chaxi for tea, which have roots in ancient China, but were, at that time, being imported into Taiwan via Japan - and with Japanese flavor, not ancient Chinese. The new sidehandle pots being made were assimilated into Taiwanese "gongfu tea," a term that, as we said earlier, has become a generic reference for any Chinese tea. They used sidehandle pots as they would Yixing, pouring from them into a pitcher and then decanting into small cups.

The first great influencer we know of, who may be responsible for bringing sidehandle pots to shine again in Taiwan, would be Chen Qi Nan (陳啟南), whom you can read all about in the March 2014 issue of Global Tea Hut. He was the first we came across, though there may be other influencers as well. He was also the first to popularize using wooden handles attached to kettles and sidehandle pots, a trend that has influenced the work of many potters we admire, like Peter Kuo (郭詩謙) and Luo Shi, who are discussed at length in this issue.

Though the resurgence of sidehandle pots in Taiwan is a great addition to our tradition, we have found that much of the innovation in teaware over the last few decades has been based on a growing market of tea drinkers, coupled with a desire to create unique looks and styles that set a potter apart and make him/her successful as a potter. All too often, teaware makers don't drink enough tea. They aren't grounded in tea-brewing traditions and rarely understand the history and makeup of the wares they create. Without the spirit of a love for tea and tea drinking, a potter will never capture the essence and spirit of tea in a way that really, truly inspires Chajin and brings the greater joys that teaware can provide to a tea session, and, ultimately, to a life of tea. There are wonderful exceptions to this, of course, like the three potters featured in this issue (including the amazing and talented Petr Novak, who has a deep connection to tea and stands out as a great Chajin, and, as a result, one of the most esteemed teaware makers of this generation). As a result, the sidehandle pots being made in Taiwan come in a variety of styles, often with more of a focus on how they look, rather than how they will be used and in what way. There are, therefore, a huge array of sidehandle pots, including flat kyusu-like ones, pots created to be held in the modern method of using the thumb on the button/pearl (which we will discuss in the sidehandle ceremony manual later in this issue) and many other styles. Many of the Chajin who favor using sidehandles strive for simplicity in tea, so wood-firing and simple, unadorned styles and glazes, like wooden handles, appeal to this kind of tea lover. Though they are often beautiful, if we wish to practice sidehandle tea in the tradition of the Hut, we must also pay attention to the function of the pot as well, as not all the modern varieties are suitable for our purposes.

Later in this issue, we will offer you a manual for sidehandle bowl tea ceremonies, much like we did for leaves in a bowl ceremonies in the February 2017 issue. We consider the creation of the sidehandle bowl tea ceremony to be the greatest innovation of our generation of this lineage. We are very proud of this development. Every tradition must evolve to suit the times. If it does not, it will live in old buildings and books rather than in the hearts of those who practice it. But we must also be careful with adaptation, as it can corrupt the power and intention of a tradition. In order to adapt and grow teachings and ways, one must first understand them. I would actually take this a step further and say that one must become them. It was seventeen years before I made any adaptations in this practice. Once you practice to a depth at which you become the method, then your adaptations are not imposed from the outside - such change is an evolution from the inside out. This kind of development is the tradition changing and growing itself, in other words.

It is important to remember that one can have the form and shape of a practice, but not its spirit. You can take the form home, but it will be hollow without the soul that informs it. Only humility, respect and transmission can fill the bowl with more than tea; only in honoring the source of our practice can it grow and flourish into the future. Looking around the world, the myopia of the modern age, forgetting our common indigenous heritage (we all come from indigenous peoples) and losing touch with all the old-growth cultures of the world has polluted the earth and the human heart. This is not to say that I feel it would be intelligent to go back to older, more primitive lifeways, or that doing so would even honor our ancestors. But if we do not understand where we have come from and learn to build upon the foundations of our ancestors and their culture, spirituality and relationship to the Earth, we flounder in a cultureless, spiritually vacant dystopia of consumerism and concrete. In other words, we have to know and honor where we have come from in order to build the world we all deserve, not to mention a world in which our descendants can once again walk the Earth with dignity and pride, as opposed to the shame the modern landscape inspires.

Without reverence and deep understanding of where a method comes from, it will not really thrive and flourish in one's life. My Zen master always used to say that there are students and there are thieves. Students come to humble themselves, creating vessels in their hearts to receive, consume, digest and ultimately become the teachings and tradition. These students then go on to become teachers, adapting and growing the tradition to new forms that better suit the new times, places and people it is serving, but they do so with a reverence for their teachers and the teachings, and with a permission granted by years of training and deep understanding of the methods, as much as that granted by their teachers themselves. Thieves want to take from the lineage and use the teachings in whatever way they see fit, often to adorn themselves, like badges or medals. Without training though, they change the teachings in ways that they themselves don't even see as detrimental, let alone out of a deep understanding. When we would ask my teacher about what to do with thieves, he always said, "Let them come. You cannot steal from a stall where everything is free! And maybe what they take will open their hearts, and then they will return as students, ready to learn and become the teachings."

As we have discussed in past issues, the bowl tea tradition we practice was designed to be simple and unadorned. We practice bowl tea to make tea accessible to more people around the world, and to reduce tea to its simplest form: leaves, water and heat. This facilitates a more direct communication with Nature and Tea, which then goes on to inform all the tea one learns and practices as one develops in tea. Learning to receive Tea, Her messages and spirit is the foundation of a good tea practice. All of the human culture and brewing methods are second to that. Music played on great instruments to catchy melodies is poppy, but vacuous. Music with soul, on the other hand, is powerful. One of my heroes, Jerry Garcia, said: "The purpose of music has always been sacred. The music industry can prevent music from doing what it was intended to." The same can be said of tea, or any other art.

Bowl tea steps into this to remind us of ceremony, of our love for the Nature that makes tea. Bowl tea is, in its simplest form, about creating meditative and ceremonial space. Ceremonies teach us to remember to remember. Tea ceremonies cleanse the participants in compassion, to heal the body and spirit. Ceremonies turn attention into intention, which is powerful. A ceremony focuses our attention towards a Way of life, a Dao, and the unseen is then seen: the road to follow.

Bowl tea is not about making the finest cup of tea possible, which is what gongfu tea facilitates. Bowl tea is to let go of the evaluative mind of "better" and "worse," which have no absolute truth. Ten grams of the most expensive tea on earth and ten grams of the lowest quality when placed in a forest become twenty grams of dirt. And the bugs, frogs, sun, rain and trees don't care which we think is "better." Bowl tea helps wash away the pretensions of cultivating a tea practice. It brings balance to our tea, allowing us to just sit with tea however it is, and there is no "too hot," "too bitter," "too this" or "too that." There are just leaves, heat and water. There is just Nature and us, without aim or method. There is method in the conducting of the ceremony, but none in the reception of the bowl - the drinking of a bowl in a bowl tea ceremony is without teaching or method, just pure Nature unadorned. There are the clouds the water was in the last fortnight, the sun and rain, mountain and wind that made the tea, and a human to feel and celebrate it all with gratitude and love. That is a bowl tea ceremony in so many words, but all the poets on earth, writing for centuries, couldn't capture the essence of a single bowl drunk in this way!

Long ago, all tea was processed very simply: It was picked, often withered and then sun-dried. This tea was all boiled or steeped leaves in a bowl, which is suitable to simple, rustic tea. In the last few centuries, however, there has been an explosion of processing techniques, creating a vast array of tea spanning Asia. And many of the kinds of tea available today are no longer suitable to be prepared leaves in a bowl or boiled. Compressed teas, for example, would come apart, leaving bits that would be in the way of drinking. Some teas would brew up too astringently if you just put the leaves in a bowl. In the beginning, when we only had gongfu tea and leaves in a bowl, we asked new students to stick to simple, striped teas, like Elevation or maocha from Yunnan. This is nice, but we wanted a way to carry the simplicity and ceremonial meditativeness of bowl tea to more kinds of tea, allowing us to use this style of brewing in more settings and with a greater variety of tea. For that, we'd need a vessel.

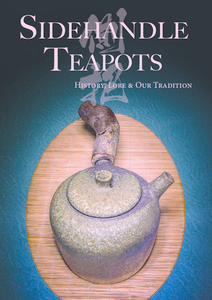

When searching for a vessel to create bowl tea ceremonies with the same spirit of leaves in a bowl, it was only natural to choose the vessel so many Chajin throughout the ages used, from the Cloudwalkers to Baisao: the sidehandle pot. We chose to start commissioning sidehandle pots in the most traditional style, with upward-angled handles, commemorative of the days when these vessels were used to boil herbs, including tea. This brought connection and depth to the ceremony, and provided a much-needed element in bowl tea ceremonies, allowing us to use many kinds of tea that were previously only brewable gongfu. It used to be that we used simple, striped teas for leaves in a bowl ceremonies and brewed everything else gongfu. Nowadays, we still save the best teas for gongfu brewing, which brings out their greatest potential, but we can prepare bowl tea ceremonies with compressed puerh, all-bud teas and much more.

Developing a sidehandle pot ceremony was not an attempt to complicate bowl tea. It shouldn't be regarded as a movement upwards towards "higher" or more skillful brewing. The sidehandle pot is, instead, a tool to expand the places, times and types of tea we can brew in the same spirit of leaves, heat and water that informs a leaves in a bowl ceremony. Our ceremony connects us to all the Chajin throughout time who have used these simple vessels to share tea spirit, commune with Nature and find the stillness inside. The sidehandle pot has been on an amazing journey, serving rivers of tea filled with heart, hospitality, kindness, ceremony, meditation and bliss. In our tradition, a new bowl tea ceremony has been created and slowly refined and honed into something that we hope will last long into the future, providing the next generations of Chajin a way to connect to ancient tea wisdom and share this spirit with others.