|

|

From a very early age the noble Lin's third son Chung Chi was inclined towards the religious life, and it was therefore no surprise when he came of age and asked his father for permission to leave the household, casting off the Red Dust of the World. His father assented and blessed him for the last time.

Chung Chi spent ten years living in a monastery at the foot of the mountains. He was a devoted monk and walked with reverence. He was humble before his master, the abbot, though often distant. His heart lay deeper into the forest, higher in the mountains. The comings and goings of lay people and all the rituals, as well as work, distracted him. He felt his answers were in the heavier waters at the bottom of the lake.

Like any master should, the old abbot saw this sorrow in Chung Chi's eyes. One day, as they were drinking tea, the master told him: "Near here, deep in the mountains, past the oldest tree and Dragon Falls, there is a monk like you. He was once my dharma brother. We shared the same master - the previous abbot. When our master passed away, we agreed that I would stay here and run the monastery and he would retreat to the mountains to find enlightenment. He promised that if he found the Shadowy Portal he would leave me a sign, to comfort me in my old age. One morning, I found this at my door..." He handed Chung Chi a shiny, black stone. It seemed otherworldly, humming with power. It was translucent and glassy, and he could see himself reflected wavy and distorted in its depths. "Take it," continued the old monk, "and go find him. He knows all about that which you seek."

Chung Chi thanked his master and headed off into the mountains. He searched for days all around the Dragon Falls, but found nothing. After two weeks he gave up and returned to the monastery. He wasn't crestfallen, though. He had permission to wander, which put his heart at ease. Once every fortnight, he would leave before dawn and spend a few days roaming the mountains - an occasional, reassuring touch to the stone in his pocket, encouraging him to hope. Just knowing that enlightenment was possible for him was solace enough.

After a year or so, Chung Chi finally stumbled upon a small clearing, and there beneath some very old tea trees was a small hut. He waited there a few days, but no one came. Having a destination made the walk into the mountains all the more enjoyable, as did the warm hut to sleep in. The master was never there, but Chung Chi began to care less and less as time passed. He started finding great joy in the walk - the mountain air, clean water and quiet hut. He was in no hurry. He had the stone and knew where the hut was. Over the years, Chung Chi's trips to the mountain hut changed him. Even his duties at the monastery weren't so bad. He began to accept them, sometimes even enjoying the rituals and chanting. The mountain seclusion and communal life in the monastery began to be stitched into the robes of a single life, the distinction fading away over time.

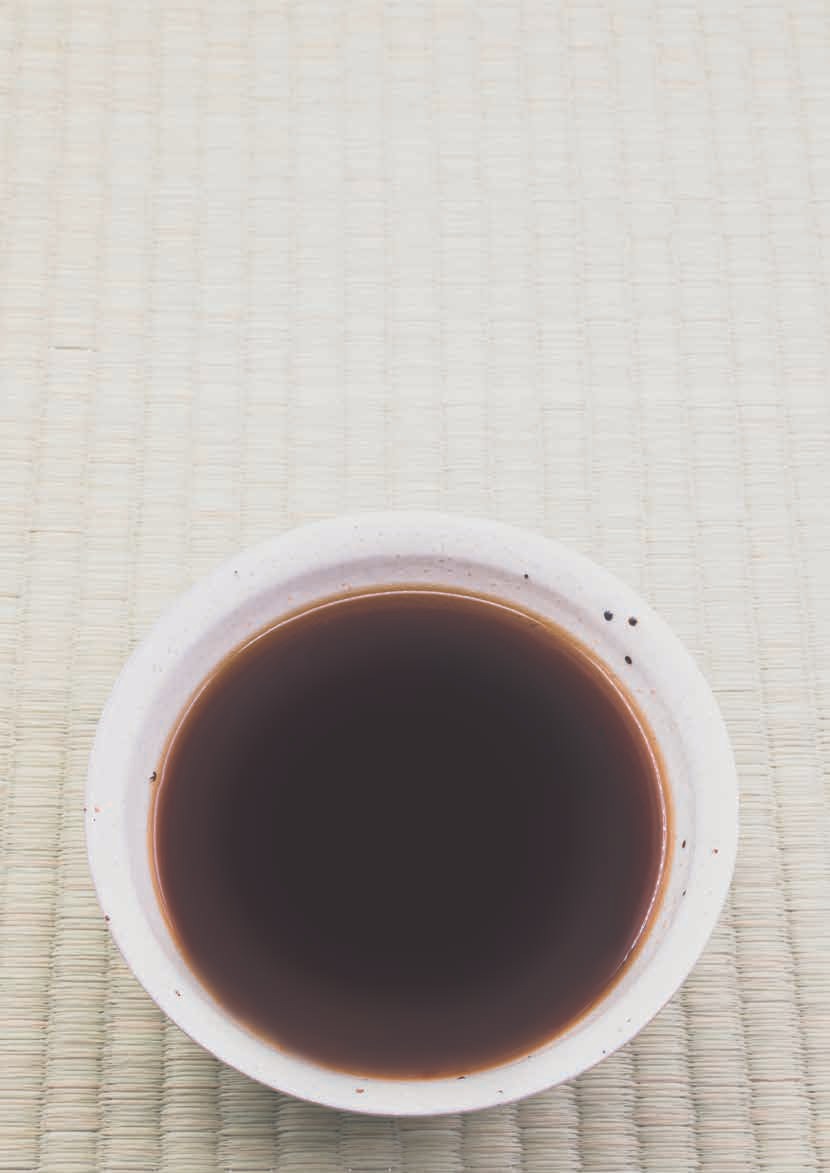

Around that time, Chung Chi returned to the hut one day and to his great surprise found that the fire was still burning, the coals still alight under a thin layer of ash. And there on the table was a tea bowl and some leaves from the nearby trees. He was radiant, thinking the hermit had surely left these for him - which meant he knew he was there. He drank the tea and sat enjoying the quiet of the hut. This continued, and each time Chung Chi arrived the tea, bowl, fire and water would be waiting for him.

A few more years passed and Chung Chi forgot all about the master and his quest. He still went to the hut, but it was for the tea, fresh air and quietude. He'd meditate and drink tea there for a few days and return to the monastery when his food ran out. One autumn afternoon Chung Chi was sitting in the hut. He had just finished his tea and was meditating contentedly, noticing how marvelously the trees changed colors. He was very surprised to hear some footsteps approaching. A shadow filled the doorway. When the figure stepped in out of the light, Chung Chi was amazed to see the abbot, his own master, standing there. Chung Chi understood everything. He prostrated himself. Then, rising up, he opened the old man's hand and placed the worn stone in his palm. He didn't need it anymore.

In all the vast volumes of sutras the Buddha taught over forty-seven years the word "nibbana" is barely mentioned at all. He never spoke of enlightenment, and dismissed inquiries when it did come up - usually by witty scholars or monks trying to intellectualize. Instead, he taught about this life: our own winding way across this earth. You can't practice what is taught anyway, and there is no need to discuss the things that should be lived.

When you get rid of ideas of enlightenment and delusion a lot of mind-made complications also dissolve. The idea that Truth is only living in remote mountains is one such distinction. The Dao is the movement of this universe, in all places and even through humanity and all its creations. It is difficult sometimes to recognize that the side of human existence we label "negative" is also a part of this vast and perfect universe. We want to envision imaginary worlds where such things as human greed and violence don't exist, but those worlds aren't real. We live in this one; and in this world human nature is thus - as it is. "Ya ta bhu ta" were words the Buddha did repeat often - unlike "enlightenment" - and they mean precisely that: "as it is, not as you would like it to be." Only when the sacred and profane have unified can you see what the Buddha meant by "suchness" and why he called himself "Tathagata" - "the one who has walked thus."

In ancient China, before the dawn of civilization, sages were seeking to communicate with the universe by retreating to the mountains where they could look deeper into themselves. With great insight, they chose to call the great movement of this cosmos "Dao," which means the "way" or "path." It is of course impossible to capture the universe and condense its meaning into a word, but in reference to that movement why not choose a word like this, which already corresponds with the road we all travel - making the journey of our life itself a reference point towards ultimate Truth.

When you are searching for something and working towards something, you lose sight of the path, focusing instead on some imaginary goal. And the path is the Path, which means that your own silly game is stopping you from seeing that which you yourself are looking for. Instead, seek out the universal in the particular: find the Dao of Cha, and you'll have found the Dao.

When you are bent towards the goal of a new and better you, the focus is still on the ego - albeit a bright, shiny and golden ego. Only when the monk in this cup-story stopped looking and started enjoying the mountain paths for their own sake did the master start leaving him some warm tea to refresh the end of his journey. And only when the journey and goal had both been forgotten, merging into non-duality, did the master himself appear to verify his student's awakening - though he had actually been there all along. Everything becomes alright when we stop seeking - the answers just fall into our laps.

In the annals of Zen, masters often use the metaphor of "strolling through the mountains" to refer to an existential freedom from logic and discriminative thought patterns, wandering free of all attachments, as the monk began to do in this cup-story. Thus in the famous koan, the student asks the great master Chang Sha exactly where he'd gone on his "stroll." "First, I followed the aroma of fragrant grasses, then I returned trailing scattered blossoms," he rejoins.

The true master works from a distance, until the student is ready to recognize how ordinary a master is. Then the game of master and student is seen for what it is: more drama. In drinking the tea and walking to and from the hut, the monk found the insight himself. This cannot be taught, because it's already here. You just need to discover that you are what you seek, and then all seeking ceases. Then you can have a cup of tea.

My master can teach of Zen and meditation, or even answer philosophical questions; but all that is too often confused with ego stuff: isms and schisms, arguments about points of logic, traditions, opinions and beliefs. He can fulfill that role, but it isn't the one he shines in. If you instead ask him with earnestness how to clean a teapot, his eyes light up and everyone around becomes transfixed in Presence - here and now focused on this teapot and its cleaning. Could there be a better discourse on Zen?

The greatest truths aren't just in the forest or mountains. Even if you move to the mountains, won't you bring your mind? Would you be seeking states you thought were higher or better? And would your mind think you had achieved something through your renunciation?

Maybe it's better to let go of enlightenments and delusions and just see how alive you are. Isn't it marvelous that the universe evolved from stars to minerals, minerals to life - and then after eons transformed into these very eyes and mouth?

If it helps, rub the Zen stone - knowing that the masters and buddhas of before have left us sutras to show that enlightened living is possible. But try to drink as much tea as you can, living here in your only life. Then maybe one day you will also find you can return the stone, sure that there is always another empty pot waiting to be filled with leaf.

Leaves and water Crafted by the heart, Not the hand. Prepare tea without preparing, In the stillness at the center of Being.