|

|

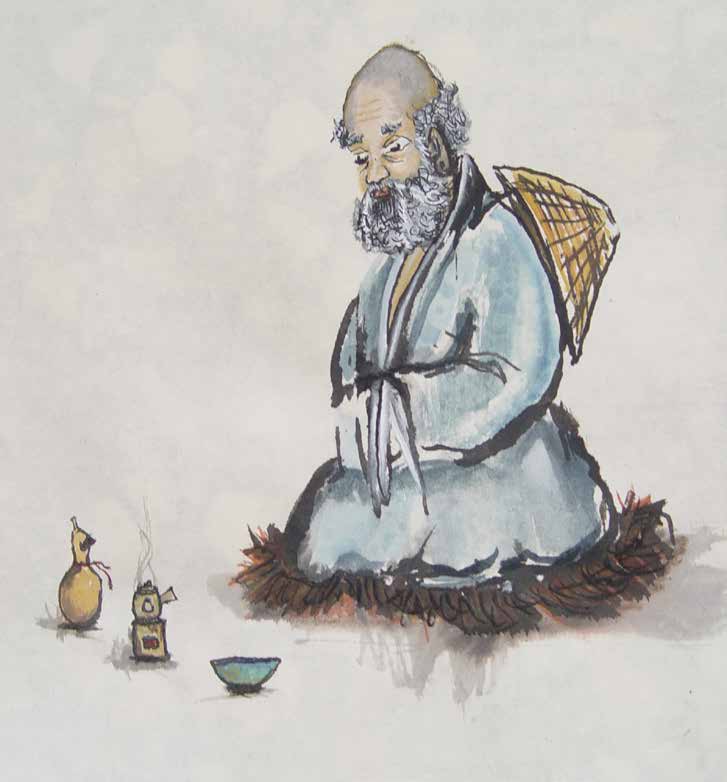

Imagine yourself a pilgrim in the early 18th century, strolling through Japan's cosmopolitan city of Kyoto. All around you pink and red plum blossoms fall like snow. Scholars sit around small tables drinking tea whilst debating Confucian literature. An exquisite array of small artisan shops greets you as you amble by. You join the myriad locals heading across the beautiful Fushumi Bridge on the eastern bank of the Kamo River. It's the weekend and an exodus of bright, expectant faces are departing to visit a waterfall or the Shingon temple or to tarry a while in a cool forest grove. Imagine your surprise as you pass a tiny shop no larger than a snail's dwelling. Above, in beautiful calligraphy, is etched: "The Shop that Conveys You to Sagehood". But it's the proprietor who really makes you stop in your tracks as you squint through the doorway. Dressed in a white garment bordered in black, a "Crane Robe" favored by Daoist recluses in China, he's the thinnest person you've ever seen. He must be about sixty or so. You immediately feel sorry for him. When he notices you, he greets you with the brightest smile and the warmest eyes that you've ever encountered.

Brewing tea in a cluster of pines customers one after another imbibing for a single sen one cupful of the spring; Friends, please don't smile at my humble existence being poor doesn't hurt you, you do that on your own.

Captivated, you go inside and sit down. His face lights up further as he begins to brew some tea in exquisitely exotic bowls you have never seen before. They must be from faraway lands. The brewing method is like the other street vendors, but this man has a loose-leaf tea that smells like the essence of Nature Herself. He smiles again, showing the three teeth that haven't deserted him. To your left, you notice painted on a bamboo tube the following words:

The price for this tea is anything From a hundred in gold to half a sen. If you want to drink for free, that's all right too. I'm only sorry I can't let you have it for less.

Poet, tea-master and calligrapher of bygone days, Baisao exists today not only in our imagination, but as one of the tea heroes who inspires and guides our tradition. For instance, every month the community here travels to an organic market in neighboring Taichung to offer tea Baisao-style to curious wayfarers (for zero sen!). And any of you who left a donation at the Tea Sage Hut will remember the rustic wooden box by the front door. Here we pass on money to the next guests, so that they may enjoy some days in Baisao's shop too. If we could read Chinese, we would see inscribed on that box the same verse as Baisao's tube.

Baisao's integrity, austere Zen practice, love of Nature and generous tea spirit are an inspiration to us all. Over the next three months, we will chart his life, and we'll start by following the first half of Baisao's journey and all that led up to his decision to abandon the traditional monastic life in favor of becoming a tea seller.

Baisao was born in 1675 in a castle town in the smallest province of Kyushu, Japan. He became a novice Zen monk at eleven, entering a monastery of the newly formed Obaku sect. This school was heavily influenced by Chinese Zen, so young Baisao immersed himself in traditional Chinese literature. He was well versed in Confusion classics and ethics, and also rigorously trained in calligraphy and etiquette. Under the abbot, Kerin Doryu, he took on the religious name Gekkai Gensho. The main practices of his tradition were sitting in zazen, studying sutras and precepts, and repeating the mantra of Pure Land Buddhism: "Namu Amida Butsu (Homage to Amida Buddha)".

Gekkai quickly bonded with Kerin and became his attendant on travels around Japan. In his twelfth year, he toured famous sites and temples in Kyoto, giving him his first experience of the city he would grow to love so much. Throughout his teens he furthered his travels. Then at twenty-one, he set out on a Zen pilgrimage to train with other teachers around the country. When he returned six years later, it seemed like Gekkai was an ardent young monk. Regularly seeking out isolated spots in cloud-hidden mountains, he strove to achieve the decisive breakthrough. However, in a letter to a friend after a ninety-day session his progress was still "not to his satisfaction". He must have been doing well enough, though, because at thirty-two he became Tenzo (cook) of a monastery nearby, a position of extreme importance in the Zen life.

At forty-five, his Master became incapacitated and was confined to his bed. Apparently, Gekkai never left his side, showing great devotion to the old priest until the master quietly passed away. Instructions were left for a younger student, Daicho, to be the old master's successor. However, he was on a pilgrimage, so Gekkai became acting abbot - a position which he did not relish. In fact, evidence seems to suggest that he had turned down the role before Daicho was asked. Humble to the end, Gekkai lived by the ethos of the following humorous Japanese verse about self-effacement:

Don't beat the drum Don't blow the flute Don't be the front Be the lion's rear!

Gekkai seems to have been desperate to leave, and wrote to Daicho twice that year reminding him to return quickly to his duties. The second time he even sent the absentee his Kesa (the symbol of transmission) with the letter! Finally, to commemorate the anniversary of his teacher's death, Daicho came home. Once the new abbot was installed, Gekkai was free to begin his new life. At the age of forty-nine, he headed off in the direction of his beloved Kyoto.

At that time, much of Japan's social structure was extremely rigid and repressive, but in the old capital, Kyoto, a more lenient attitude towards individual freedom of expression prevailed. Kyoto, therefore, was the destination for many young writers, artists, and scholars. As was fashionable at the time, many shared an infatuation for all things Chinese. There is little doubt that Baisao (as we shall now call him), with his profound knowledge of Chinese literature, skills as a poet and calligrapher, and unconventional lifestyle, had a strong influence on these young men. But perhaps the most important factor was his way of life. In a time when the average monk would do anything to fill their belly, Baisao's strength of character and austere Zen were seen as a denunciation of the decaying religious and social values. As Norman Waddell points out in his excellent biography, Baisao: The Old Tea Seller:

"In a society characterized by lockstep conformity, many citizens respected and deeply sympathized with the genuine nonconformity of a man like Baisao, who had chosen to take a different path to fulfilling his Buddhist vows. His depth of attainment was clearly reflected in his face and demeanor, and his cheerful and seemingly carefree way of life penetrated all his activities, including his tea selling. Given the esteem in which he was held by the young scholars and artists at the core of Kyoto's intellectual community, it is not surprising...that so many attempted in various ways to emulate his example."

This austerity is clearly seen in this extract from Baisao's Opening up Shop at Rengeo-in:

Life stripped to the bone I'm often out of food and drink yet I offer an elixir will change your very marrow

Originally, when Baisao set off from the monastery, he had planned to lead a wandering life as a mendicant priest, subsisting on donations. But as we shall see later, Baisao became increasingly reluctant to accept donations, so after ten years of increasing hardship, he decided to settle in Kyoto and sell tea for a living. Baisao was now sixty, and it is around this time that he adopted the name we all know, which means 'old tea seller'. This sobriquet was commonly applied to tea peddlers who roamed Kyoto's streets selling an inferior grade of green tea. This was typical self-deprecation from Baisao, who liked nothing more than to poke fun at himself, as this extract from Three Verses of Self-Praise shows:

Ahh! This stone-blind jackass with a strange kink in his brain he turned monk early in life served his master, practiced, wandering from place to place seeking the Essential Crossing. Deafened by shouts beaten with sticks he had a hard time of it weathering all that snow and frost still couldn't save himself. Growing old he found his place became an old tea seller begged pennies for his rice.

In reality, Baisao knew he was an accomplished tea master. His tiny shop was called "Tsusen-tei (The Hut which Conveys You to Sagehood)", which is also the name of our center, so he knew his tea was special. We can see his confidence in several of his poems, including the following extract from Twelve Impromptu Poems (Wu De's favorite):

Set up shop this time on the banks of the Kamo customers sitting idly forget host and guest they drink a cup of tea their long sleep ends awakened, they realize they're the same as before.

So, we'll thank Baisao for the tea, maybe drop a sen or two in the bamboo tube, and leave our friend to his new shop for now. Next month we'll backtrack a bit and examine his monumental decision to start earning his own livelihood, actually a serious breach of the monastic precepts. We'll also follow him round Kyoto and his travels across Japan as more and more of his Zen and tea became one flavor.