|

|

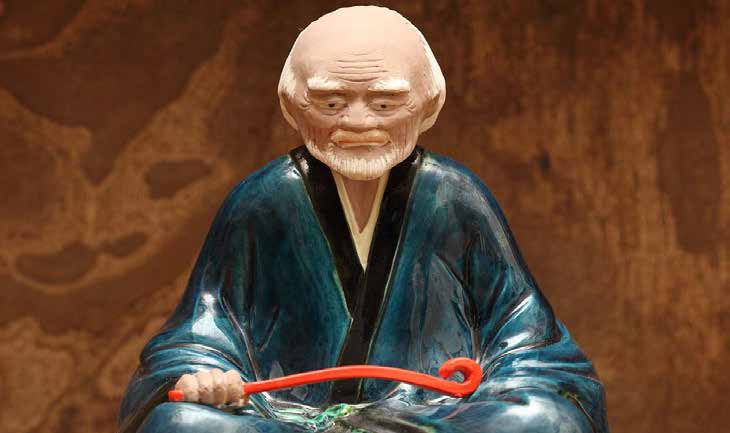

A couple of months ago, we left Baisao, our old tea-seller friend, in his 'Snail's Dwelling' shop on Fushimi bridge and wandered, slightly tea-giddy, through the bustling streets of eighteenth century Kyoto. He had entertained us with stories of his early life as we supped, his kind face beaming across the table.

His demeanor had turned earnest and a little pensive as he spoke about his decision to sell Tea whilst still a member of the Buddhist clergy. It was violating an important Buddhist precept that prohibited priests from earning a living. His eyes had moistened a little. He was supposed to live from begging food and donations, but he had found the latter too much of a compromise. He spoke of the priests he had seen "seeking greedily in every way and at every opportunity to obtain donations from lay followers." His head had shaken: "When they are successful they toady to their new benefactors, wagging their tails and showing more respect and devotion than they do their teachers or their parents." Often too, the lay-people's donations came with subtle (or unsubtle!) pressures. It had not been an easy decision to go against his tradition. He had even tried accepting no donations for many years, but had nearly starved to death on several occasions. So, in the end, Baisao had decided that it was more tainted to receive impure donations than to handle the meager money that he earned himself from Tea.

We remembered the conversation vividly. Baisao had turned to us like a child with his toothless grin: "Now, with the money customers leave me, I am able to purchase small amounts of rice that keep me alive and enable me to pursue a way of life that satisfies my deepest longings." He had laughed: "People regard tea selling as one of the meanest occupations on earth. What they despise, I value immensely. It is a life that gives me great joy." Inspired, he had spontaneously burst into a poem as he poured another bowl of Tea for us:

Set out to transmit the teachings of Zen revive the spirit of the old masters settled instead for a tea-selling life. Honor, disgrace don't concern me the coins that gather in the bamboo tube will stop Poverty from finishing me off.

Baisao had certainly come to the right place to immerse himself in Tea and Nature. The Jesuit priest, Joāo Rodrigues, who had spent nearly four decades in the capital just before Baisao was born, wrote:

The people of Kyoto take much pleasure in lonely and nostalgic spots, woods and shady groves, cliffs and rocky places, solitary birds, torrents of fresh water flowing down from rocks, and in every kind of solitary thing which is imbued with Nature and freedom from all artificiality . . . On going out of the city one sees everywhere the loveliest and most delightful countryside of all Japan... Many people go and recreate in the woods and groves of the outskirts... every day crowds of people from the city enjoy themselves there.

Over the years, Baisao moved his base a lot. Before long, he began setting up shop near temples and scenic spots. He transported his tea gear, including a heavy brazier, in two large bamboo baskets at the end of a balancing pole on his shoulder. Once at his destination, he would spread out a thick paper mat toughened by persimmon juice tanning, and put up a banner adorned with the words "Pure Breeze". He would then make Tea for other Nature-seekers and often compose poems with them to commemorate the occasion. He would continue selling Tea only until the tiny sum of twenty sen had accumulated in his offertory tube, then the Tea was free for all. A typical encounter is described in Opening up Shop in a Grove Before Hoju-ji:

In a grove of tall bamboo, by an ancient temple steam rolls from the brazier in fragrant white clouds; I show you a path that leads you straight to Sagehood can any of you understand the lasting taste of spring?

Often too, Baisao would seek out beautiful spots to be alone, as in Going to Make Tea at Shin Hasedera:

Footing it eastward over Duck River urged along by the autumn wind I sit alone with my bamboo baskets feeding the fire with autumn leaves. Pines thresh up at the summit shrilling quietly inside the brazier gentle voice of the Great Being resonating deep within my heart.

Baisao's Tea furnishings must have been viewed with great curiosity by his customers. Among the teapots, cups, braziers and other utensils were articles of great rarity, presumably obtained from Chinese priests and laymen residing in Japan. At the time, the word 'Tea' meant powdered matcha for most Japanese. Baisao, however, mainly served a new loose leaf variety that came to be known as sencha, a word that translates as "simmered tea" since most teas of this variety were boiled. This kind of tea was introduced by Chinese Buddhist priests in the late seventeenth century. (In more recent times, sencha has come to mean Japanese loose leaf tea.)

We know from his poems that Baisao brewed more than one kind of Tea. His writings include mention of brewing Chinese loose leaf Tea sent from his home in Hizen. And on many occasions he writes about using a loose-leaf Tea from Shiga. There are even allusions to a superior Chinese brick tea, flower-scented tea as well as Wuyi Cliff Tea. However, though he may have used imported leaves from China on occasion, he probably relied most heavily on the early versions of sencha that Japanese farmers were starting to produce at the that time. When this process was perfected later in Baisao's life, the results were a beautiful jade-green colored Tea with a wonderfully sweet flavor that could easily be brewed in a teapot. It is this Japanese Green Tea that Baisao is credited with introducing to the capital.

At sixty-six, Baisao returned to his native province, Hizen, to obtain a special permit for all who roamed outside its borders. Whilst there, he officially resigned his position in the priesthood and returned to lay status. He took on the name, Ko Yugai, a combination of his family name, Ko meaning 'high' or 'lofty' in the sense of a person of lofty pursuits, and Yugai meaning 'roaming beyond the world'. Around this time, he composed the following verse from Three Verses on a Tea-Selling Life:

I'm not Buddhist or Taoist not a Confucianist either I'm a brown-faced white-haired old man. People think I just prowl the streets selling tea, I've got the whole universe in this tea caddy of mine.

As Baisao approached the last decade of his life, there is evidence in his poems that his austere Zen practice was beginning to reap rewards. As he comments in Composed in a Dream:

Pain and poverty Poverty and pain life stripped to the bone absolute nothingness only one thing left a bright cold moon in the midnight window illumining a Zen mind on its homeward way.

Such utterances of a Zen nature begin now to appear more frequently in Baisao's poetry. In fact, at some point in his seventies, the man who had said he was not cut out to be a Zen teacher had a change of heart and started taking on a handful of students. His poems now become full of references that the Insights of Zen were becoming his own. In Admonitions for Myself he states:

Your life is a shadow lived inside a dream, Once realized 'self ' and 'other' vanish. Pursue fame, the glory of a prince won't suffice; Take a step or two back a gourd dipper's all you need. No matters in the mind passions quiet themselves Mind freed from matter means suchness everywhere. The moment these truths are grasped as your own the mind opens and clears like the empty void above.

And in Written for the Wall of Master Shinsan's Study he reminisces:

There are times sitting idly at the open window I reach the hidden depths of the immortal sages, times, rambling free, beyond the floating world I ascend to the heights of the wise men of old.

At the advanced age of eighty, the combination of declining physical strength and recurring back pain made it impossible for Baisao to continue selling Tea outdoors. Poignantly, he took his favorite carrying basket, Senka, ("Lair of Sages"), two of his bamboo offertory tubes, and a small flat piece of bamboo root he had carved into a tray for his teapot, and burnt them in a fire outside his dwelling. The eulogy he composed serves as a great example of how we could value our own precious teaware:

Senka is the name of the bamboo basket in which I put my tea equipment when I carry it from place to place. I've been solitary and poor ever since I can remember. Never had a place of my own, not even space enough to stick an awl into. Senka, you have been helping me out a long time now. We've been together to the spring hills, beside the autumn streams, selling tea under the pine trees and in the deep shade of the bamboo groves. Thanks to you, I have been able to eke out the few grains of rice to keep me going past the age of eighty. But I've grown so old and feeble I no longer have the strength to make use of you... I shall go off... and wait for the end. After I die, I don't think you'd want the indignation of falling into worldly hands, so I am eulogizing you and then I will commit you to the Fire Samadhi.

From then on, Baisao could only sell a little Tea in his shop. But, because of his growing fame, his calligraphy became sought after, and he was able to earn a little supplementary money selling inscriptions, some of which still exist today. Having said that, there were periods where he nearly starved, and at times he was only able to survive through the gifts of friends. Indeed, his back incapacitated him for the whole of his eighty-first year. But it wasn't all doom and gloom. Resilient to the end, he still apparently enjoyed excursions with friends viewing maple trees, climbing the small hills behind his dwelling, brewing Tea in distant Arashiyama, and moon-viewing until after midnight with a poet friend. As he says in a poem of the time:

Trudging eastward long ago callow youth of twenty-two I see I've come full circle now a sheep-ox year once more. Eighty-three springs on me moving in a timeless realm sauntering the Way at leisure a goosefoot staff in hand.

Baisao finally passed away at eighty-eight. In a scene straight out of a movie, apparently his friends were able to hurriedly print a collection of his writings and press the book into his hands as he lay dying. The volume is the now famous Baisao Gego (Verses and Prose by the Old Tea Seller). Many of the dying man's friends had become leading figures in the cultural flowering of this period in Kyoto.

One of his final calligraphy inscriptions still exists today. On it, Baisao's insight and humor are as clear as ever:

Going far away to China to seek the sacred shoots Old Esai brought them back sowed them in our land. Uji tea has a taste infused with Nature's own essence a pity folks only prattle about its color and scent.

Next month, in the final of my three pieces on the Tea-sage from Kyoto, I have the good fortune to be interviewing Wu De about Baisao's connection with our own Tea tradition.