|

|

In Taiwan, many cities and towns are known for their specialties, both quotidian and sublime. One town is known for roasted sweet potatoes, while another is known for its handcrafted woodcarvings, and a third is famed for its roasted oolongs. As Chajin, one of our favorite towns to visit is the pottery town, Yingge. And in Yingge, our favorite potter is Peter (Kuo Shih Qian) at Da Qian.

Peter's side-handle pots are sculptural forms with wooden handles and ash glazes. Their speckled surfaces are comprised of a muted color palate - white, powder blue, moss green, French grey, hematite, ochre - yet their subtle color and texture variations dazzle the eyes. Some portions are matte; others crystalline, iridescent, glimmering. Some are smooth; others scratchy and nubby. But beyond their appealing surfaces, they are consistently brewer-friendly and tea-centric, which says more about their function and feel than their form. You might guess that their maker spent decades perfecting his craft. And you'd be wrong.

Peter is only 30 years old, which makes him about 20 years younger than your typical shop-owning artisan in Taiwan. But his success at such a young age makes sense in the context of such a pottery-centric life. Peter was born and raised in Yingge, and spent many hours of his childhood playing in his uncle's ceramics factory. But it wasn't until he was 18 years old, rapidly approaching graduation from Taiwan's most prestigious arts high school with a major in sculpture, that he first began to work in clay.

A chance meeting with a local pottery teacher got him hooked on the medium, and he spent the next few years earning money to pay for ceramics classes and further his studies. By age 23, he was working with ceramics full time. He taught ceramics classes to tourists in Yingge as his main source of income, but continued to actively experiment with forms and techniques all along. Over the years, his experience, resources and skills grew. In 2006, he rented an old teaware factory, renovating it extensively to make it into a ceramics classroom and studio, where his own work only occupied a small shelf. And in 2008, a major shift occurred - he started drinking tea with a local Chajin and began to produce teaware borne out of the practice of drinking and "feeling" tea. That same year, he began to study under a famous wood-fired ceramics teacher, and learned to use this firing method to produce ash-speckled wares akin to those discussed in the January issue of Global Tea Hut. He fell in love with the technique, and by 2011 he had built his own woodfiring kiln, where he continues to fire ceramics every two months. Then, in 2013, he turned his classroom into a showroom, shifting his focus from teaching ceramics to producing and selling teaware.

In the short time since Peter opened his gallery, he has produced several collections of teaware. Each collection is marked with its own small, stamp-like "button". Though each has its own distinctive look, there is a continuity of some essential quality behind the pots, so that each group fits cohesively into Peter's larger body of work. He said the differences in each collection are there because he prefers not to produce large quantities of a particular style for money. Rather, he prefers to make things slowly, creating each piece as a unique expression of the feeling he wants to share. And perhaps this is where the continuity within his body of works arises. Peter said this has to do with the work being genuine: "The feeling cannot be fake. The art cannot be fake. You can feel the connection with the pot every day when you use it."

Indeed, just as with serving tea, creating pots which truly express something meaningful cannot be faked. And the meaningful expression behind Peter's pots is one of peace - the peace that he finds in drinking tea. He said the main reason he started to craft teapots was because he started to really drink tea, and to feel calm and peaceful while drinking tea.

Furthermore, Peter said that when he does not have peace in his heart, he cannot perform his craft. Without peace, his pots get skewed on the wheel. With peace, even when he is firing teapots for four days straight without any sleep, he can do well.

Over cups of Taiwanese oolong tea, Peter said his ideal teapots communicate the peace of tea and work harmoniously with the overall chaxi to create tea sessions that are smooth throughout the entire process of serving tea. He said there is no one perfect pot, because there is no one perfect way to have a tea session. He added, "Each is a unique expression, and a single teapot cannot express all of a person's spirit."

Peter spends his days (and many of his nights) mixing clay, building pots by hand, drying wood for the kiln, firing his wares, adding final touches, and selling his pieces. When I asked about his favorite part of the process, he closed his eyes for a few moments, swaying his body back and forth a bit as he considered each step. Then, his eyelids flew open and a wide smile spread across his face. Animated, he answered, "Each part is different, and each part is good. But there are two moments when I am especially happy. When I am driving to the kiln to fire and when I open the kiln and see my artwork, I feel very excited."

These two moments seem to capture much of what Peter's life work is about: a strong drive to create and a relishing of the results, always with an eye on what can be done differently next time. There's a sense of play behind it all, a sense that Peter is creating these pots for the joy of creating them, and making them better each time around because that's simply what makes him tick. And that same sense is threaded through each step of his work, from clay to the tea table.

Each collection of pots starts with Peter geeking out about clay, and delighting in doing so. Studying under a wood-firing master, Peter learned how to mix his own clay for wood-firing. He didn't know how to mix clay for teaware, but he did know how to enjoy tea, so he set about learning to evaluate clay mixes for teaware. Now, he has a process for doing so: First, he mixes a batch of clay using raw materials from all over Taiwan and sometimes also from America. Then, he tests the mix out with a firing. He sees what a pot made of the clay does to water and, if the result is positive, he tries it out for tea. Finally, he hones in on the mixture he wants before he begins making and firing pots.

After the clay body is ready, Peter begins to build teapots. His education in sculpture helps him create innovative three-dimensional forms, but he doesn't favor the usual "art pots" you'd expect from a former sculpture major. Instead, Peter prefers to fashion relatively simple side-handle pots instead of more unconventional forms. He said this is because side-handle pots allow him to experiment more, and because they enable tea brewers to do the same. He said he loves to play with form and that he continually experiments to improve function, and it would seem that he wants to allow those using his pots to do the same in their tea serving.

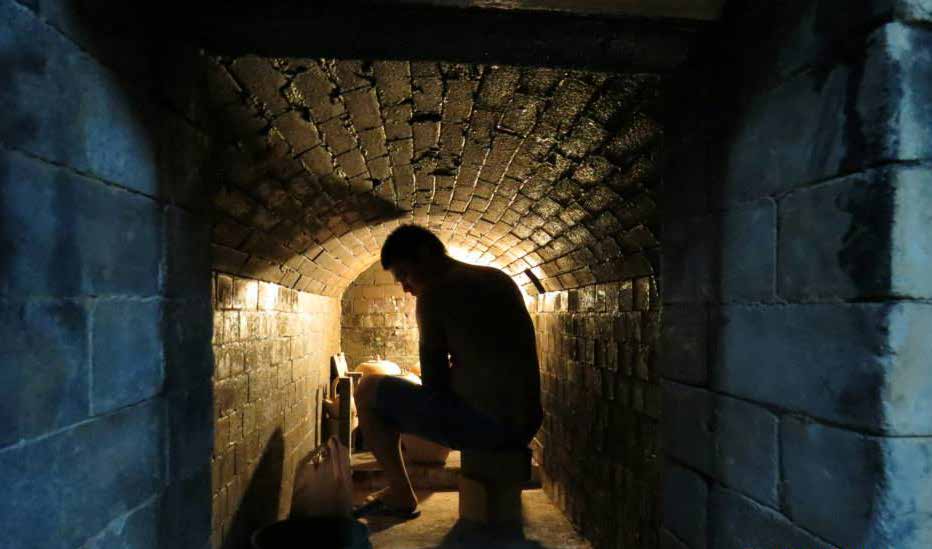

After Peter has constructed his teapots, he turns to the local lumber factory for scraps. Then, he dries these odds and ends thoroughly in preparation for the firing. (He was, in fact, doing just this until 6 AM on the day of our interview.) Next, he stacks his works in a three-square-meter kiln. The kiln can hold as many as 20 large pieces (such as tea jars) along with many more small pieces. And once the kiln is loaded, Peter is ready to start firing.

The active portion of wood-firing takes four days, and aside from the occasional nap, Peter doesn't stop to sleep during the process. Fueling the fire with the wood he has dried, he works the kiln up to a heat of around 1400 degrees Celsius (a blazing 2250 Fahrenheit). As the kiln gets hotter and hotter, he watches for visual signs of its progress, relying on these indicators rather than a thermometer to see when it's time to coat the ceramics with ash. He said the ash starts melting at around 1200 degrees, but he waits for the reflective, blue-green glow of the pottery that appears around 1400 degrees. It is then, on the fourth day, that he adds a batch of firewood through a special side-door in the kiln, directly into the pottery chamber of the kiln. Under the extreme heat, the firewood is instantly transformed into ash. The ash scatters down over the ceramics below. As it touches down on their blue-hot surfaces, it melts, spreading outward over horizontal surfaces and downward over vertical ones to form fantastically organic and un-plan-able colors and shapes as it expands. But Peter won't see the results of the ash's dispersal until a week later, when the kiln has cooled to a manageable temperature and he can open it safely.

After Peter has removed the works from the kiln and inspected them to see what makes each one special, he works on some final touches. These include cleaning and smoothing their surfaces and adding wooden handles to pots. Peter said he usually uses charred bamboo roots for handles. This is in part because of bamboo's poetic associations in Chinese culture. (Virtuous people are called "bamboo" in some old Chinese stories.) But more importantly, it's because the nodes in the bamboo root make the handle easy to hold, and because the oils in your hands will change the color of the handle with use over the years, so the pot evolves with you and your brewing.

When his works are complete, he is ready to sell them at his shop, Da Qian. He runs Da Qian with his partner of five years, CiCi. The couple greets guests as most pottery shops in Yingge do - with tea. Next time you make the trip to share tea with us here in Taiwan, set aside a day to take a jaunt in Yingge and to pay a visit to this talented local teaware artisan. Like many visiting Chajin before you, you may just find your new favorite teapot in his shop!