|

|

Through scenic tea mountains, down a simple village road and tucked away in a small garden studio lives one of Taiwan's greatest treasures, a potter that has contributed so much to the culture of tea here and abroad that it's difficult to find the words to express his influences. For authors there are always some topics and people that we long to write about yet falter since we hold the topic in such high esteem that we're worried we won't do it justice. As a tea lover and author living in Taiwan, Deng Ding Sou is just such a topic, and not just because of his awards or fame, but because he truly is an important and amazing person. I always knew that one day, I would write this article, approaching it now as ever with excitement and trepidation both. I don't want to just list his achievements or put forth his biography, which has been done in countless other articles - I hope to capture a bit of his distinct personality and the effect it has had on modern tea culture here. If I succeed, this tour through his life will leave you with as much respect as I have for him - as a friend, tutor, fellow tea lover and artist.

Deng Ding Sou was born in Jiayi County in 1959. From an early age his artistic talent was recognized. He grew up painting, practicing calligraphy and dabbling in other art forms. He started working in clay at a very early age, and fell in love almost immediately. He also fell in love with Tea at an early age. He studied ceramics with different teachers around Taiwan for many years. In 1981, he started an apprenticeship under Master Chen Jing Liang to learn ceramic art. His teacher taught him more than just the technical skills of molding teapots, using a potter's wheel and kiln, or even the unique knowledge of stones and ores that his tradition passed on - his master also encouraged a spirit of independence in Master Deng, suggesting that he utilize tradition as but a stepping stone for his own creative endeavors.

It wasn't long before the student was shining brightly on his own, and his unique approach to tea culture and teaware in particular started to make him famous. There are two aspects of Master Deng's character that separate him from other artists in the tea world. As I contemplated and realized why he was so special, it dawned on me that perhaps these are the very traits that have always pushed the brightest artists of the tea world to the front of the crowd, now as in ages past: Firstly, Master Deng doesn't create out of any financial motivation. If having passed through his years of the cliché 'artistic suffering' isn't enough, one need only follow his career. His compassion for the people of Taiwan and his courage to experiment with new trends and ideas - to come to know that he is someone who creates for the love of clay, and would do so alone on a mountain with nothing but homegrown herbs and vegetables as he would appreciated and awarded, as he is. In fact, his fame has done little to change his personality or way of life: he still lives in the mountains in his simple studio, still teaches for free, and his shelves are filled with pots and good teas, not the many awards he's received. And those teas bring us to the second factor that makes a great artist of teaware: Master Deng is as true a tea lover as ever there was. Far too many artists that create teaware do so because it is lucrative.

Many sculptors and potters in China and Taiwan get involved in making teaware because it sells. They bring their skills in painting, glazing or design to teapots and often make very beautiful teapots, cups, pitchers, etc., but the problem is that much of this teaware doesn't function well. Destined to sit on shelves and look nice, much like the ceramics in the traditions many of these artists migrated from, such teaware is dulled by the fact that it won't ever embrace Tea or bring joy through sharing. The best teaware has always been used, and antique pots and cups glow with life because they have made so much tea, and brought so much joy to tea lovers over time. The true tea lover is saddened by the cup that is behind glass, knowing that it is dying. Even priceless antiques are preserved and cared for in the tea world - because they are alive; they are handled with care and respected as they participate in our tea sessions. That life is much of their elegance and the true measure of their craftsmanship.

Master Deng always puts function first and aesthetics second. He says, "If you can't use the teaware I have created, I might as well make a vase or pot for you to display. I could do that as well. I chose to make teaware because tea is my greatest passion in life. I myself drink tea every day, so I know what it is like to buy a pot that you thought was so beautiful only to get home and find that it doesn't pour well or leaks. There is one pot like that which sits on my shelf there." He sighs and points to an elegant pot, "it sits there collecting dust and still disappoints me when I pass it, glancing at what could have been." Not only is Master Deng's teaware inspired by a true love for tea, it also is based upon decades of mastery over the art. In other words, he is also a tea master. Learning about the deepest intricacies of gongfu tea and practicing every day for decades with the eye of an artist has given him countless ideas. "I watch the tea ceremony with an artist's eye: when a pot breaks or doesn't function well, when a lid stand doesn't hold the lid well or when a pitcher pours improperly or decreases the temperature of the water too quickly, I always think 'How could I fix that?', and then I experiment." Looking around his studio, I realized that this was the understatement of the decade! There are broken bits everywhere, failed attempts and countless sketchbooks filled with inventions and designs.

These days, Master Deng actually does more inventing than he does artwork. His own handmade pots, pitchers, cups, etc. are often made as templates that are then produced in limited quantities by factories throughout Asia. He showed me one of his sketchbooks and I was amazed to see five corrections, in so many pages, to problems I myself have encountered in my own tea preparation, including a new design for a tetsubin he is developing with a Japanese company that will prevent the spout from dripping or leaking and has a gorgeous wooden - rather than metal - knob, so you can remove the lid without tongs. I asked him about it and he led me to a shelf filled with about ten such tetsubins that he had rejected, adjusting things before sending them back to the producer. His clever smile in such moments is unforgettable.

"If the inspiration for artistic creation derives from life and from culture, then each of the ceramics that I create is a portion of my soul - a hyperactive soul that is constantly bounding around, never at rest. If the works that I have produced have helped to make people's lives better in any way, then that is only an accidental reflection of the good side of my personality."

For ages, it has been known that stoneware is ideal for tea. The two most famous kinds of teaware, Yixing and porcelain, are both stoneware. There are many reasons for this: on the most subtle level the spiritual master would say stoneware is elemental, and its use related to the Earth and the Qi such teaware imparts to the tea liquor. The scientist would perhaps argue that the porous quality of stoneware, at least in unglazed pots, allows it to absorb the oils in tea and enhance future brewings; the potter would say that stoneware has less reduction which makes it easier to fit lids to pots, hand-mold handles, etc.; the tea lover would reply that stoneware has a simple aesthetic that fits well with tea preparation. The truth is that all of these reasons, and many more, courted the marriage between stoneware and tea culture over time.

Master Deng learned ceramics in a tradition that blends various kinds of stones with clay to produce unique and innovative textures and styles of pottery. With his love for tea and childlike brilliance and inquisitiveness, it wasn't long before he began to explore the possibilities that certain kinds of stones were suitable to certain aspects of tea preparation, rather than just decorative addition. Again, it's always function first with Master Deng. "After all, everyone who loves tea knows that Yixing teapots are so great because the stone ore that they are derived from is so special. I realized that the Earth is filled with many kinds of stone and ore. Why not experiment? Perhaps some of them would end up making great tea." Master Deng spent decades exploring the relationship between various teas and stones like volcanic basalt, andesite, turquoise, and many, many others. "Some stones enhance water or keep the heat in the pot, while others are purely decorative", he said. When I asked for more details, Master Deng smiled and said that much of that information was secret. It is traditional for Chinese master artists to be copied, and the more famous they are, the more this holds true. And Master Deng is very famous! Nevertheless, he told me that he does pass all of this on to his students freely.

Master Deng said that such stoneware was a powerful expression of elemental wisdom. The Earth element in the tea ceremony is represented by the teaware, and such stones are deep statements of this. He allowed me to drink some mountain water from a few of his cups and I was amazed to find that each cup changed the texture, smell and/or flavor of the water dramatically. When we later sat down for tea, he brewed the same tea in an average porcelain pot and then in a stoneware pot designed for that kind of tea. I was again astonished at the improvement it made. He smiled and poured the tea from the earlier, porcelain pot into a stoneware pitcher of the same kind as the second pot. To my surprise, even a minute in the pitcher had almost the same effect as the stoneware pot itself on the tea: the tea was smoother, moister in the throat and tasted cleaner and brighter.

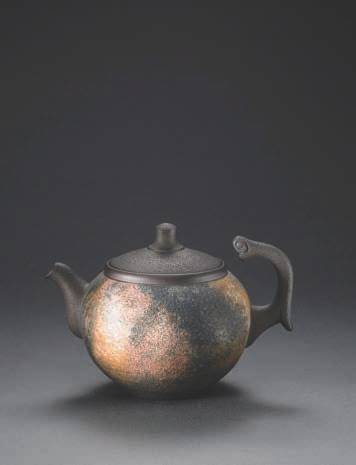

"In a 'rock teapot', the pot becomes a canvas on which the ceramicist can express himself. Employing a wide range of different stone materials, the teapot maker uses the firing process to create textures and patterns that combine the beauty of traditional brush painting with the elegance of oil painting. These pots have the simple beauty of earth and stone, and the radiance of metal. They may be speckled with spots of light, like scattered stars in the heavens, or they may display the warm luster of ancient bronze or gold vessels; bold wild patterns are complemented by exquisite attention to detail. In these pieces, the beautiful aesthetic qualities of ceramics and metals are united as one in a new way. The multiple strata of visual effects, from the dark and subdued through to the shiningly radiant, create a form of self-expression that is based around natural elements, and over which the human artist can never hope to exercise complete control. Each piece has its own unique character, and no individual piece can ever be replicated exactly; this is where the special charm of rock teapot creation lies."

Early in the morning of September 20th, 1991, Taiwan was hit with a massive earthquake of 7.7MS. The prone island often suffers major and minor trembles, though nothing like this one. When the day dawned, the rest of the world sadly watched the news: thousands had been killed or injured, while a huge crowd of others were left homeless. The earthquake's epicenter was in central Taiwan, near the city of Taichung, but most of the loss occurred in Nantou and Yunlin counties, which are central to the tea industry and culture of Taiwan.

Of course, all Taiwanese were affected by the news and relief efforts were begun domestically and abroad. Having so many friends whose farms or businesses had been directly affected by the earthquake, Master Deng also decided to get involved. He moved to Nantou County and started to help at some of the farms. Together with his students, he purchased large quantities of the volcanic ore and stone that had been uprooted during the quake and used it to produce teapots. He started using his name and art to hold shows around Taiwan and abroad, generating relief and awareness through art.

While this was already more than what most were doing, Master Deng realized as he lived in Nantou longer that it wouldn't be enough. "I thought of the old proverb that if you give a man a fish, you feed him for a day; but teach him to fish and you feed him for a lifetime", he says. Master Deng opened his studio and with it most of the secret knowledge he had inherited and developed over the years to the citizens of Nantou. Anyone affected by the earthquake was free to come and learn pottery, use his kilns and develop a new trade for him or herself.

Immediately, students were eager to learn from Master Deng. Today, their stoneware pottery is found all over Nantou and has not only provided a financial basis for rebuilding much of what was lost, it has also helped to attract valuable tourism to this part of the island, allowing for the creation of other forms of industry as well. Some of his students have gone on to fame of their own. I met one who had lost his home in the earthquake. He said his life had lost all meaning and he had turned to drinking day and night. He needed direction, which he found in clay. "It was easy. Most of them love tea, and every tea person loves good teaware - so it wasn't as if they were uninterested. It was the clay that really healed them", says Master Deng modestly.

Most of the tea farms are rebuilt now. Master Deng still stays in Nantou teaching pottery to this day. We traveled to a few local tea farms and plantations and it was obvious that everyone, even the next generation, respected him, knowing the contribution he has made to Taiwanese tea and tea culture over the years, and especially through troubled times.

Of Master Deng's many contributions and innovations to tea culture, none is as famous as his legendary Guyi teapots. I asked Master Deng about them and he said, "About twenty five years or so ago I started drinking tea avidly. I delved into the process of extracting the best liquor from tea leaves. After I acquired some skill at brewing tea, I started to think about how I could design a teapot that would meet my tea-making needs and would be uniquely my own." Like any lover of tea, Master Deng began to collect antique zisha teapots from the legendary "Pottery City", Yixing. One day when he was pouring tea for himself and his teacher the lid fell off one of his favorite teapots and cracked on the table. Most all people who drink tea seriously for some time must pass through the loss of some treasured teaware, broken or cracked by our clumsiness as we learn the process of gongfu tea. At first, Master Deng was also distraught, looking down at his loss in awe (which funny enough is just how I reacted when I broke one of my Yixing some years ago); but then, as is its wont, inspiration capriciously struck, flashing through the clouds of loss. We can only imagine Master Deng's gaping mouth slowly sculpting into a grin.

He told his teacher he had to go and quickly raced home to do some drawings. What resulted was the first ever Guyi teapot. The Guyi teapot is unique because the spout is on the bottom of the pot, rather than the side, which allows gravity to pour out the tea. As Master Deng began to experiment with this new teapot, new innovations followed over the years. He improved the rest that the pot sits in, perfected the seal to trap the air by holding one's finger over the button, and started designing new ways of decorating and even adding his knowledge of stoneware to create some Guyi of that variety. From his own description of Guyi teapots:

"As with traditional teapots, the Guyi pot exploits the power of air pressure. By covering or uncovering the air holes, you can control the flow of water within the teapot. With the Guyi pot, however, the tea flows out from an opening near the bottom of the pot. Because water naturally tends to flow downwards, the flow is smoother, and it is much easier to ensure that all of the water has been removed from the pot. (At the same time, because the teapot is always in a horizontal position, there is no need to worry about the lid falling off)."

The Guyi teapot was an immediate success in Taiwan, and even though Master Deng invented it so that we wouldn't break the lid of our favorite pot, I think its success was more because of the effect it has on tea preparation, especially when brewing the tight ball-shaped oolong tea that is so common in Taiwan. When brewing ball-shaped oolong tea, the key to making great tea is to have the balls all open at the same time, uniformly, so that each releases its essence together in a symphony of flavor and aroma. In the first few steepings, as the balls are still opening, this can be difficult to do with a normal teapot because the balls often shift to the side when we are pouring, which sometimes traps some of them and prevents them from opening at the same time as the others. This problem can also be solved by skillful pouring of the water over the tea and teapot, but I have found that a nice, round Guyi teapot really does the job excellently. Because the ballshaped leaves never shift, and the steeping pours out through the bottom, every steeping - including the initial ones - are all even and pure representations of that tea. I especially like the designs he has made that are rounder, allowing for more space for such oolong tea to unfurl.

As Master Deng mentioned above, the Guyi pot also helps to ensure that all the water drains from the pot. If, like me, you enjoy having your tea over long periods of time and enjoying it slowly, this can be important with certain kinds of tea. If the water isn't all removed, the leaves will stew in the pot and detract from future steepings and/or reduce the amount of steepings one gets from a tea. In that way, a Guyi teapot can help increase a tea's patience. This just furthers Master Deng's trend of putting function before form. Guyi teapots can be exemplary of all great teaware because they are aesthetically pleasing and function well in equal measure.

Because of its popularity, in the late 90's Master Deng started designing series of Guyi pots to be made from molds. He has made one series per year, creating only about 500-600 pieces, which are then shipped to different regions of Taiwan and abroad. The pieces are numbered and the molds are destroyed after the process so that they can never be replicated. Even these production pieces are often worth money these days.

As mentioned earlier, it is often the mark of a master in the Chinese arts if he or she is copied, and of course Master Deng's success, coupled with the fact that he has so freely passed on his wisdom to so many students, has resulted in the creation of many kinds of Guyi teapots in Taiwan and abroad. Some of them mimic his style and design, while others are even made of plastic or glass and meant to provide convenience. When I traveled to America for the World Tea Expo in the summer of 2007, I was surprised to see many devices for steeping tea that were (probably unknowingly) based on Master Deng's invention. I told him about that and he was happy. He said, "The idea is a good one and it should be shared and used." I think that more than just copying him, many ceramicists and other artists have also been inspired to try new things and innovate because of the success Master Deng has achieved with his inventions. Master Deng's Guyi teapots have shown other artists that tradition should be a guide rather than a master, and when it is possible and rewarding, creative ingenuity can create great teaware.

Master Deng and I sat down for tea after our interviews, glad to have the formal stuff over with so that we could go back to being friends and brothers in tea. As an author and student of Tea I find that my taste in friends is much like my taste in tea and teaware. The artists, producers and tea drinkers that attract me the most are the ones who truly love Tea. Without knowledge of tea brewing, teaware never really reaches the level of mastery; and the same can be said about the teaware that is made commercially, without a deep passion for Tea and Nature. Nowadays, many tea businesses are using the "we love tea culture" ideal as a marketing philosophy, suggesting to customers that they sell out of love for tea rather than for money. Master Deng is way above all such vulgarization. He is unpretentious, warm, friendly and humble. As soon as you sit down for tea with him and see his childlike joy as he opens a homemade tea canister inscribed with the words "Crappiest stuff on Earth", which he assures you is to mislead potential thieves from the fact that this jar actually holds the "good stuff" - when you see that smile, you cannot doubt his passion for tea. Master Deng's carefree and unimposing personality, innovative and inventive mind and his skill with stone and clay have merged, like leaves and water, with his love for tea, and like his pots made a lasting brew that stays in the throat and returns to the memory long afterwards.