|

|

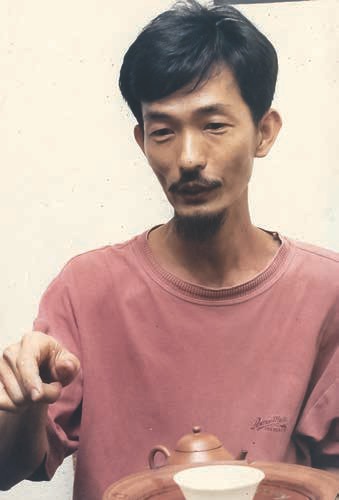

Holding up an old Ming Dynasty tea jar, a sparkle glimmers in his eyes. "Still in love after all these years!" he exclaims. The old jar is simple earthenware that nine out of ten people would probably pass by without remark - warbled and asymmetrical, it has a simplicity that belies hidden beauties beyond or within what some would call defects. But a true love sees through the flaws, finding endearment in the imperfections. Just as some widowers find that what they miss most about their departed companion is all the quirks and foibles that distinguished their character, Master Lin has with every passing year grown fonder and fonder of his old jar and all that surrounds the Leaf it contains. And in the moment when he held up that old vase, the shimmer in his eyes was a window into a lifetime devoted to Tea.

Looking back on all the precious time I have spent with this living master, Lin Ping Xiang, I see in it the apprenticeship and transmission of a kind of Zen spirit, as it's told in so many of the tales that have inspired my journey. They say that Zen began when the Buddha and his students were sitting for evening discourse on Vulture's Peak. After some silence, crackling with expectation, he held up a single lotus. That was his sermon. And one monk, Mahakasyapa, understood the lesson. From that unspoken transmission, the spirit of Zen was handed down. This wordless way is always steeping in and pouring out around Master Lin, waiting to be drunk by those who come with empty cups. And yet, he is like that Ming vase: outwardly simple and unremarkable. You'd pass him by on a street, unless your eyes were tuned to that something else - those hidden beauties resting just beyond and within the ordinary. You can talk to him for hours about the most banal things - how's so and so, or this tea and that - and yet find yourself leaving the conversation transformed, with a new perspective on life, especially as seen through the lens of the so-called "commonplace".

There is a story of a young monk that ordained long ago in Japan. He was one of only three apprentices at a small temple. Day in and day out, the monks worked and meditated in relative quiet. The young monk felt frustrated that his master didn't teach more. There was the occasional lecture, but it wasn't enough. After some time, he asked permission to leave and travel, which was granted. As he traveled the length of Japan, seeking other temples and masters, each abbot would ask him where he'd come from and who he'd ordained under. When he'd tell them his master's name, in every place north to south, they'd exclaim that his master was the most enlightened teacher in Japan - congratulating him on how lucky he was to study with such a one. This baffled the young monk. Everywhere he was met with laudatory compliments for his master, the very same teacher he’d found wanting. After enough of this, he realized he’d missed something and decided to head back to his master’s temple. When he arrived, he asked his old teacher, “Master, I studied here for two years and you never taught me your Zen. Everywhere I traveled, I was met with renown for your understanding of Zen. Was I unworthy? Why didn’t you teach me?” The old master smiled, “Never taught you my Zen? Did I not wash my bowl after meals? Did I not lay the coals for tea while you gathered water?”

Like the young monk, I see many people pass by Master Lin without noticing the way he sees, the way he walks or the way he unpacks his bag full of tea and teaware. At first it feels like a shame, but then I remember that he wants it that way, and of course he does. Master Lin is more of a Daoist sage. The Zen filters are mine. But in this case, the treasure in the common cup is an insight they both share. There are also plenty of Daoist tales of seekers who head up into the mountains looking for the sage. On the way, they stop and ask a woodcutter or fisherman for directions. He points them along… They never find the immortal, and return home dejected. Later, they tell the friend who met the sage—the one who sent them on their trip—that they couldn’t find any immortals in the mountains, “only a simple woodcutter.” The surprise in such stories always comes when they describe the woodcutter to their friend, only to find out that he was the sage! Master Lin is that woodcutter-sage: a simple, down-to-earth guy you share some tea and a chat with. And if you ask him for directions, he’ll steer you away from himself to some other empty spot in the woods. Then, you’ll return dejected, only to find out the simple Tea master was the sage!

If you come to Master Lin looking for spiritual teachings you won’t find any. But that’s only because he is a spiritual teaching. He doesn’t talk about how to live, he lives it. He talks about Tea. And if you want to learn about Tea, you won’t find a more knowledgeable source! He is an encyclopedia of forty years of Tea knowledge. He can tell you firsthand how each tea is made, where it comes from, how to store it, brew it and appreciate its dry and wet leaves, liquor, fragrance and mouthfeel. He’ll articulate sensations in your mouth that you never even noticed were there until he named them, drawing your attention to aspects of a tea you were missing out on— aspects that you now enjoy so much you wonder how you ever lived without them. He truly loves Tea. Whenever I ask him why he makes such great Tea, he always answers, “I just love Tea!” And that isn’t just a witty response. The insight is an appreciation of the fact that real mastery has to come out of love. Nowadays, it’s a rare thing to meet a master who has thrown himself so completely into his passion and Way. It takes a deep and lasting love to appreciate something so profoundly for decades, devoting your life to it. Master Lin’s love of Tea is contagious. Every time I return home from some time with him, I brew more tea and with more verve and a love rekindled. He inspires me. And, oh God, with moist eyes, I can’t help but write that I love him for it. With all of my being.

If you leave more informed about tea and inspired to brew more, he’ll be happiest. But from him, you can also learn the deepest of spiritual lessons, just not in the words you are used to hearing. To do that, you have to shift. You have to see the Ming Dynasty jar the way he does. You have to notice the way he walks, the way he sits down; the way he looks at you approvingly or disapprovingly depending on your mind. You have to really see through the woodcutter to see the immortal. And then, many more and deeper lessons are transmitted. From him, I have learned how to live Tea— not just brew it, but really live it. I’ve learned to love simplicity, and to guard my life from clutter. His teachings on how many teapots you should have apply to all material things. You may not notice that he doesn’t have a cell phone, and never has, but I’ve noticed. The way he navigates life in a modern, complicated world, and does so with grace and wisdom, is a teaching of the highest order. All too often, we pass by the common things—the rocks and trees, shafts of sunlight through a window, etc.—looking for so-called “higher” states, places or teachers. But the best teachers are often right under our noses. Master Lin and the Tea spirit he embodies have taught me to find the spiritual in the world, and to cultivate a love for the ordinary. As I walk that journey, I realize more and more that there is no “ordinary”, only glory and magic. The so-called “spiritual” life is this life, if it is anything at all!

The true master doesn’t have disciples because he wants to lead them, but because he has so much to share he is overflowing. He doesn’t have any private ambitions for his students. He is not a master of them, but of himself. His every gesture is a teaching. And in his eyes, the student finds their own truth mirrored. In his presence, they feel more present themselves. As the inner stillness increases, the student comes to understand that the power was never "outside"; it was always in the self. And that is when the transmission happens. The master was being himself, and that radiance helped create a sun-field in which the student's inner seeds could sprout. Then, the student realizes that the master they've always sought looks just like them!

Master Lin is that woodcutter-sage: a simple, down-to-earth guy you share some tea and a chat with. And if you ask him for directions, he’ll steer you away from himself to some other empty spot in the woods. Then, you’ll return dejected, only to find out the simple Tea master was the sage!

Lin Ping Xiang was born in the Year of the Horse 1954, in the small town of Kuala Pilah. His father was a rubber estate foreman who migrated to Malaysia at the age of fourteen from Meizhou, Guang Dong, China. He came along with his brothers to start a new life. Master Lin never met his grandparents, since they stayed behind in China. His mother was Malaysian Chinese. As he grew up, Tea was always around, a part of the everyday life of simple Chinese working class people. Master Lin's family was poor, but it didn't matter because there wasn't another side of the fence to look across. Everyone lived meagerly. It was another time, one that seems softer and harder at the same time, at least from the photos of his generation.

He was a good, well-behaved child - the youngest and favorite of the family. "Even my sister loved me so; what to say of my mother and father!" He was obedient, keeping to himself. When he was in the fourth grade, the family moved to Bahau, a small town near where he was born. They stayed there until Master Lin was in middle school. Then they moved again, this time to Kuantan, on the east coast of Malaysia. Master Lin was a great student. Even today, he has one of the sharpest memories of anyone I know, especially when it comes to Tea information. He remembers data, quotes, poems and numbers in great detail, and sometimes you're left in awe, wishing you had your notebook as he lists the chemical composition of porcelain glazes, the degrees of firing and other minute details of their production, and then recites word for word three ancient Chinese poems about them in the stride of a single paragraph! You can see the lifelong destiny of a great teacher echoing back through his years as a brilliant student, for great teachers are always great students. A teacher has a lot to teach because he's learned a lot. When he was a young man, Master Lin's Chinese was excellent compared to most of the ethnic Chinese in Malaysia. And since much of Master Lin's professional life was devoted to language, it's worth discussing further.

Chinese immigrants first started coming to Malaysia when the British controlled the peninsula to work in the tin mines and other estates there. Master Lin's father actually worked as foremen under British management. At that time, their children and grandchildren started studying in English schools, though there were always Mandarin schools as well. Parents often chose English-medium schools to give their children an advantage. Mandarin students like Master Lin, who studied at Chinese-medium schools until the sixth grade, had to take an extra year of English before they could go on to middle school. I've always found Malaysians to be the most amazing polyglots. It is not uncommon to meet people who can speak six or seven languages proficiently. Master Lin is one such example: his parents are ethnically Hakka people, so Hakkanese is his mother tongue. He's also very proficient in Mandarin, of course, and has learned fluent Cantonese, which is the language the majority of Malaysian Chinese speak. Like most Malaysians, he also studied in English schools and therefore is fluent in English as well. And, of course, all Malaysians learn some Bahasa Melayu in school. Usually, the Chinese people are modest and say their English "isn't good" or that they only speak a "little" Bahasa, but their English is amongst the best I've encountered in my travels, and from the conversations I have seen Master Lin and others have with native Malays over the years, I'd say they are as proficient in that language as well.

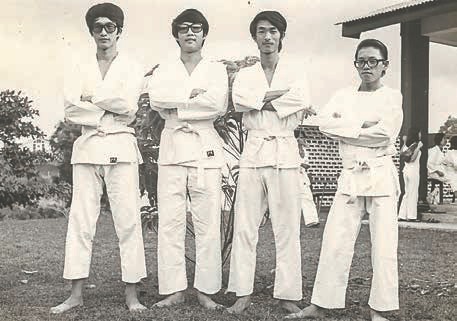

Though most Malaysian Chinese speak an incredible amount of languages, and do so well, they often can't read or write Chinese since they attended British schools. For that reason, a lot of them have tutors. Master Lin started tutoring those in grades beneath him at the age of seventeen. He says he drank tea every day during that time, and loved it as a beverage. He left home at the age of nineteen to take what Malaysians call "pre-university" classes in Kuala Lumpur, studying for two years. The tutoring, often over tea, had helped him decide that he wanted to be a teacher. Instead of university, Master Lin moved to Johor Bahru, the southernmost state in Malaysia. During that time, he started his first martial art, Tae Kwon Do. Students had to choose between Tai Chi, Tae Kwon Do or football for physical education. He jokes that only girls took Tai Chi and Chinese were terrible at football, so there was really only one choice left. After completing his training to become a Mandarin teacher, he says he was luckily posted to a junior high school outside Kuantan, which he considers to be his hometown.

In the 1970's, a young Master Lin started to notice Tea more and more. He fell in love with the Black Dragon, oolong, from his very first soar. He tried some amazing Dong Ding teas from Taiwan, which were expensive, at the homes of some of the wealthier classmates he tutored in high school. He said it struck him like love at first sight. Otherwise, he drank the more available teas from the now famous Sea Dyke Company of Xiamen, which exported Tie Guan Yin from Anxi and Cliff Tea from Wuyi. During his teacher training, he and his classmates started to actively seek out different teas. If you have a Tea conversation of any duration with Master Lin, you'll soon see that many sentences start with "In those days..." I can never get enough of hearing about "those days". In fact, I usually lean forward when I hear that, knowing that what follows will be interesting or important... "In those days, there were different grades of tea, and it was easy to learn about tea because they wouldn't cheat you." As we've discussed regularly in these pages, the quality/grade/price was much more honest than the market nowadays. "Sea Dyke had the grades AT104 and AT204 for their Tie Guan Yin teas. The 'AT' standed for "Amoi Tea" - Amoi is Xiamen. The former cost 7.50 Ringgit (US 2$) and the latter 2.40 Ringgit (US 65 cents). Most tea merchants survived selling red teas, which were popular due to British influence, with a few oolongs as well. Actually, most all teas were good in the early 1970's - even the supermarket had Wuyi teas!" The more expensive tea cost a lot in terms of a middle school teacher's modest income. But what baffled Master Lin was that he actually enjoyed the lower grades more. And he says that the question of why the higher-grade teas were better is what launched his Tea journey in earnest.

From the question of the higher and lower grade oolongs - a story I have heard from him many times, and could relish many times more - we always segue to one of his favorite topics: gross and subtle, and their relationship to quality. He says that eventually, after years of gongfu tea, he learned that the higher-grade teas were subtler and that he was mis-brewing them. "The lower-grade teas were neither this nor that. They just had a thicker, stronger liquor, which confused me. I knew the difference was in me. I had to hone my skills. Now it is easy. Something to give a kick or a punch, more on the surface, was what I wanted then. I couldn't capture something so subtle or fine." The journey of learning any art is always from the gross to the subtle. When we are less sensitive, the stronger more potent versions stimulate us more, but as we move deeper into nuances it's the subtler, refined aspects that allow us to explore deeper and richer worlds. In perfume or incense, for example, low-quality fragrances are strong and in the front. Highgrade fragrances are subtle, felt more in the back of the nasal cavity, and often not smelled until after you calm down. But that subtlety allows for much more smooth and lasting experiences, as well as room for many middle and undertones that provide a richer experience. And that is as true for Tea as it is for fragrances. The best teas are subtle and delicate. They aren't so forgiving; they require skill to brew. When you do taste a fine tea, though, it's life-changing. One of Master Lin's most famous quotes is: "Tasting is believing. If and until you try a fine tea, it's too hard to tell!" And understanding that Tea rewards those who brew Her well entices many a Tea lover into her arms. A lot of us began our journeys with just such an invitation.

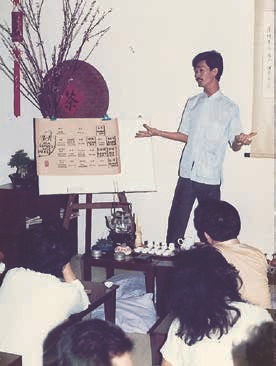

By the early 1980's, Master Lin was already brewing fine gongfu tea. In 1983, he met his teacher; a Taiwanese who would often visit Malaysia named Wu Guo Zhong. Master Wu was a student of one of China's greatest modern masters: Cheng Man Ching. Knowing that we are connected to that great lineage honors us all. Master Lin had moved to Kuala Lumpur doing various odd jobs. Alongside his tutoring, which he continued until 2001, Master Lin worked in insurance and even timber construction. In the mid and late-eighties, he also began traveling to lecture freely on Tea and tea preparation. "Many guests would think they were going to hear an old man lecture, but I was still young then. That surprised them... Aged Old Bush Xue Shian (Water Fairy) was my favorite tea then. Of course, in seeking out aged Wuyi tea, we also found a lot of aged Liu Bao and puerh. But Cliff Tea was my true love. She still is now!" At that same time, Master Lin began reading Tea literature, including the English book by John Blofeld, which he says was very influential on his journey. His newfound Tai Chi practice and Mandarin teaching experience helped make him a great Tea guide as well. By then, he was already a Chajin, with a deep passion for Tea and the same generous spirit we all admire today. You could say that such kindness defines a man of Tea.

Cheng Man Ching (鄭 曼 青) was the last of a dying breed said to be widespread in ancient China: he was a scholar, a sage, a traditional Chinese doctor and a master martial artist. They say that such men were common in dynastic China. Whether or not that is true, few survived into the modern era, and none as influential as this great master. Of course, it goes without saying, Master Cheng was also a Chajin. He loved brewing oolong tea gongfu.

Master Cheng was born in rural Chekiang Province, present day Wen Chou, in 1901. His father died at a very young age. He was said to be an exceptionally bright young boy, and the whole village had ambitions for him. But at the age of nine, a brick fell on his head, knocking the young boy into a coma. A Daoist master wandering by took notice and revived him with herbs. When he came to, he had lost all his memory. Later, his mother apprenticed him to a local artist to sweep, clean up and grind ink. One day, the artist's wife asked the boy to paint something. He demurred, saying that he'd never tried. After she insisted, he grabbed the brush and put it to paper. Out flowed a glorious wisteria in a single stroke. His teacher was amazed. When young Cheng arrived to the studio the next morning, he found an inscription from his master on his painting declaring him an artist in his own right.

Master Cheng went on to become one of the most famous painters, poets and calligraphers in China. In his mid twenties he began teaching at university. He also developed a severe and seemingly incurable case of tuberculosis. At that time, a friend introduced him to the famous Tai Chi teacher Yang Cheng Pu. After a year of herbs and Tai Chi, the tuberculosis was cured and he never had symptoms again. This spurred an interest in the young artist to study Tai Chi and Traditional Chinese Medicine, both of which he later mastered enough to teach.

In 1949, Master Cheng moved with other literati to Taiwan to escape communist persecution. Throughout the rest of his life he organized several poetry, art, medicine and martial art societies. He also co-founded the National Chinese Medical Association. He lectured extensively in Taiwan, Asia and even the West on the classics of Daoism, Tai Chi and Chinese Medicine. He had a deep spiritual practice, an artistic talent and was a gifted healer and martial artist. The grand master passed away on March 26, 1975 in Taipei, leaving behind many students around the world.

In 1988, Master Lin and his friends opened the Tea Art Tea House in Kuala Lumpur, starting a full-time life of Tea. "Sometimes I would brew tea for some guests and then when they'd leave I would think about going out to get a bite to eat or take rest. After locking up, I would head down the stairs only to find another group of people dropping in for tea. They'd turn me around and we'd head back up for more tea... And students would come to me with their life problems, as well. Being a teacher was a joy, but also hard work. Sometimes I had to sacrifice all my private time." Many Tea lovers came to that tea house to learn Tea from him, noticing already the mastery in his brewing. Around that time, he was also asked to be an advisor to one of the largest tea companies in Malaysia called "Purple Cane."

After his tea house closed in 1993, Master Lin went back to tutoring Chinese and making tea at home. He continued teaching Tea, traveling and acting as advisor to several tea houses around Malaysia. "Over the years, I officiated the opening of so many tea houses. And sadly, I've watched many close, too. In Taiwan, people live in small apartments so a tea house culture can thrive. But in Malaysia, people feel they can drink tea at home and the ambience will be better than at a tea house." A year later, in 1994, he met his closest friend and a bright "rising star" of a student, Henry Yiow. Henry was at that time, and still is, a great chéf with a passion for Tea. Henry is also from Kuantan, where he would later return to open a tea shop. (We plan to devote a whole article to Henry in a future issue, so we won't spoil too much.) Suffice it to say, the two have been working, teaching, traveling, giving and sharing tea for the last twenty years since. And Henry's a great student, exemplifying his teacher's grace in his own life. He knows a lot about Tea, brews a great cup and shares Master Lin's love for kindness and generosity. He's also one of my best friends.

Master Lin has taught in England four times, starting in 1996 when he lectured in Bristol. He went again two times in 2000, giving lectures and workshops at the Victoria & Albert Museum. He was then invited back at the end of that same year by Lipton to come teach about Chinese tea, as they were launching three Chinese teas there. He gave lectures and brewed gongfu tea in nine cities around the kingdom. He says that Lipton was kind to him, leaving him free to talk on the topics he wished and to promote the art of Chinese Tea. "In those days, we would teach about Tea anywhere and everywhere we were invited to, sometimes to political parties in Malaysia, even though we didn't really know anything about their politics."

Master Lin is full of amazing one-liners that pour out of him in the exact same tone and phrasing every time, like the measured, graceful - because they are so practiced - movements of his tea brewing. In fact, he can even say them in Chinese and English, and often does so at the same time. I adore his smile when he recites one of his quotes, like a Chinese orator from the Qing Dynasty, floating back and forth from Chinese to English. And you can always feel the way such pithy sayings affect the listeners in the room, in the way people turn inward smilingly when they hear beautiful music. Whenever he talks about his trips to England, he says things like: "Tea is the Eastern antidote to Western stress." Like others in his generation, Master Lin was technically born in the British Empire, since Malaysia achieved independence in 1957. He was therefore honored to travel there and teach, which he did again in 2012, giving lectures in London and Cornwall. He often says, "Tea is given by Nature to Mankind, not just to the Chinese or any other people."

Last year, Master Lin turned sixty. At that time, he quoted Confucius to me, who at that same age said: "Sixty years, sixty changes (六十歲六十化)." That means we always continue learning, even in our old age. He has retired from teaching now, though he fills a room with Tea spirit and wisdom everywhere he goes. He and Henry often travel to China to visit students, explore tea mountains and share tea with friends there. He has been sourcing tea and teaching Cha Dao for more than thirty years now, and mastering the art of gongfu tea for going on forty. Though he isn't formally teaching lessons or accepting students as he once was, preferring the modern version of a reclusive life, he still pops into his students' shops and gives informal teachings. He says that now meeting him for a lesson is up to Destiny. He doesn't have a phone, so when I asked about how his old students contact him, he replied: "If we meet, we meet. A Tea practice has taught me to live this way. Tea is about slowing down and living simply. The more you understand it, the simpler you long to be." In fact, when I asked him if he'd like to add any words of wisdom to this article, advice for all of you, he said: "We are living in a fast-moving world, so find an excuse to drink tea. Drinking tea is a short retreat, taking a rest to go for a longer journey."

Master Lin has never married, except to Tea. He loves freedom, and a devotion to Cha Dao. "I love traveling and sharing tea most. That has always been more of a girlfriend to me. I am happy alone, actually. Very happy. I have lived a life of Tea." He is the continuation of a long line of Tea sages who show up throughout history - out of time and out of place, preserving lost wisdom. And I doubt the future generations, ours included, will ever see one with such an all-inclusive tea knowledge as Master Lin Ping Xiang.

Master Lin's honors and accolades would be longer than an article, and not do justice to his profound Tea acumen. In Yunnan, he was heralded as one of ten great "Puerhians". He has been drinking puerh since the 1980's, and can regale you with many 'in those days' stories about great teas like Song Ping that could be found in bulks of many tongs (seven cakes wrapped in bamboo bark). He also has decades of experience aging tea, watching many different kinds of tea change in the long-term, affording him a greater expertise than all of us who've yet to see which, if any of our teas transform into jewels, and which to weeds. Though mentioning such honors is a part of a good biographical sketch, and needed for such an article, it doesn't do justice to the heart of his Tea, his mastery or his love.

Master Lin is a great teacher, kind and patient, but more importantly inspiring you to want to learn more. He's also full of Tea wisdom, both knowledge and experiential. He's read and studied so much ancient and modern tea information, traveled to the tea mountains and taught others to brew tea for decades. His students have students who have students, which is why the entire Tea community of Malaysia calls him, "Ai Ye (Beloved Grandfather)". You can always tell a lot about a teacher by his/her students. And let me tell you, the Tea people of Malaysia are amongst the best friends you could have! They are kind, humorous and gentle people, like the Master that has inspired them.

I could write for pages and pages about the qualities in him that I admire. When I look around my life, his influence is everywhere. But there is one last teaching that I am perhaps most grateful for: Generosity. Master Lin's giving nature is second only to Tea Herself. He shares and gives all day. He shares his being, his knowledge and his tea, and does so completely. He says that some teachers learn something and want to keep it in, but when you really love what you know, you want it to spread. You realize that sharing wisdom makes you happier than having it. Also, you learn a lot about something when you teach it. Master Lin often told me that he learns a lot from his students, which I now understand.

He always has a bag full of the best teas in the world. It is like Happy Buddha's endless treasure bag - similar to Santa's - it never ends! I don't know what kind of beautiful magic flows through that bag he carries, but in all the many years I've known him it has never run dry, or even diminished. It's always full of the same incredibly rare and precious teas, which flow like his heart. He never stops giving to others: around him, great Tea flows like water. To be bright within and gentle without was considered the highest virtue in ancient China. Master Lin is a gentlemen of another age and order, and one of the greatest mentors and role models I will ever know.

The generosity that Master Lin has poured into my cup over the years has informed my whole Tea journey. And that giving heart is also the spirit of our center and of this tradition. We have built this place of service and generosity based on his examples of what Tea means. Let the tea flow, constant and without anything asked in return! As such, tea is loving-kindness. For as he so often says, his tea is great because he loves it. And the only true way to love something is to share it. I needn't look far for my teacher, or the love of Tea he shares. I just put my hand on my chest and hold it there. Then, I open my eyes and pour the pot into the cups of the guests who sit here before me...