|

|

On the upward of a moisteyed bow to my host, Huang Sheng Hui, after thanking him once again for all he's done, I glance over his shoulder into the hall of the guesthouse and up at the golden statue of Xuan Zang, who long ago defied royal decry banning international travel and left China to roam around India. After sixteen years, and many adventures, Xuan Zang returned home with thousands of sutras, relics, statues and other Buddhist treasures. As I stand bowing my farewell to Master Huang, I think I understand what it must have been like to leave India for home with so many treasures, feeling as if I too were departing with a few dozen horses worth; and like Xuan Zang, most of my fortune is wisdom as well - Tea wisdom. But Master Huang dismisses my thanks with the old Chinese saying: "One house people don't talk like two house people." It's said to impart familiarity when you are being too formal. It means that 'we are family', 'make yourself at home' or perhaps 'don't be afraid to ask for anything you need'. It also expresses a kind of loving-hospitality, suggesting that you speak as you would to your own people in your own home. Often, such polite sayings deflate over time into superficial manners, but there are those rare people who are living traditions - people whose hospitality is genuine and heartfelt. The fact that it really is their pleasure to have you as a guest beams from their eyes, and you feel honored and loved. You feel the way you do when you go home. I've been fortunate to meet such traditional people now and again in my travels, but none more kind or generous than the Huangs.

Huang Xian Yi and his sons truly see the Buddha in the guest and the guest in the Buddha, inspiring me to be a better host after I return home. Every visit to Wuyi, I have felt a sense of homecoming to distant but loving family. They are gracious with their home, food, tea and their wisdom. And when you ask around, you see that others feel the same way; that they too are leaving fulfilled by a magical trip and in awe of their hosts' selflessness. The many years they lived in a small, remote village still informs their modernized lives. In that way, they are a part of the heritage and wisdom we all need to learn from if we are to create a world truly worth living in. The generosity they have shown me year after year throughout my tea journey makes them one of the greatest mentors for our center, and a powerful influence in its creation. Guiding by example, they've helped us to define the principles that we believe to be at the core of Tea spirit: sharing leaves as an act of kindness, and asking nothing in return.

From my viewpoint, the Huangs' tea is at the pinnacle of the most refined tea on Earth. Of all the kinds of tea, oolong is the most complicated to produce, requiring the most skill and management. As a semi-oxidized tea, it requires many stages to wither, bruise, de-enzyme and roll to get the right level of oxidation. This formula may sound simple, but any skill seems simple when presented to beginners in the most basic list of procedures. To the master, there is infinite variety in every one of these stages, based on the water content in the leaves, the weather, sunshine, temperature, etc. In terms of processing skills (gongfu), oolong is definitely the most refined of all tea genres. And all oolong tea processing, as well as many of the varietals, originate in Wuyi Mountain, making the Cliff Tea produced here the eldest of this princely caste of tea. Amongst such royalty, there is surely a king, just as every mountain has upper reaches, and then finally a peak - Huang Peak. If oolong is the most refined of teas, and Wuyi Cliff Tea its brightest example, the teas made by the Huangs at their studio, Rui Quan, are the last vista, from which we can climb no higher.

Like you, the sixteen people of this year's Global Tea Hut trip listened to my speech about how amazing this tea, and the family that makes it, really are; and like you, they may have thought it to be exaggerated hyperbole. After a trip there, however, everyone's heart had shifted. I hope that in the future all of you will get the chance to come with us on a Global Tea Hut trip and meet the Huangs yourself, but in the meantime let's travel there in our heart-minds, starting with a hint at why their tea is so special and then moving on to a history of their amazing people.

The Trees: First and foremost, Rui Quan tea is special because of the trees. As we discussed in the previous articles, there are four grades of Cliff Tea. The best is called "Zhen Yan" which means "True Cliff Tea". These are the trees in the park. They have the perfect drainage of steady water over loose, fertile soil. The waters run down the cliffs and bring minerals, crystals, and good pure mountain energy to the roots of the trees. The cliffs refract the sun so that the trees get only certain spectrums of light, mostly oranges and violets. They also channel mist through the park almost every day, which creates the humidity Tea adores. The cliffs absorb the sun during the day and release the heat they collected all day during the night. This means that the temperature stays constant, which increases the growing period. Beyond all the scientific/physical reasons why Wuyi is the perfect tea growing area, Buddhist, Daoist and Confucian sages have come here to cultivate themselves for thousands of years, charging the whole park with spiritual juju that influences the breadth and power of the Qi in all the teas grown there. And one hundred percent of Rui Quan's teas are True Cliff Tea from gardens within the park.

The Heart: You can make tea for a lot of reasons. You can do it to support your family or because it is what you know. One stonemason cuts bricks to certain dimensions all day. When asked what he is doing, his fellow stonemason says that he is here working for money to support his wife and children. The third man, cutting the same stones in the same way as the first two, stops and looks up with a far-away gleam in his eyes: "I am building a glorious cathedral that will house the prayers of people for many generations to come," he says. The Huangs are that third builder.

Tea has only been a commodity for maybe a thousand years, and only in earnest for hundreds. Before, and even through that time, there are many thousands of years of tea as sacred plant medicine. The terraces that hold the tea gardens in the park are made from tens of thousands of stones that were quarried thirty kilometers away and carried into the park, and then placed lovingly in ideal spots in a way that has lasted the centuries. You can feel the Human/Nature cooperation in this. Our host, the eldest son Huang Sheng Hui, told me that in his grandfather's time tea pickers had to remove their shoes before entering the garden and weren't allowed to talk at all during picking. With a bright smile and a sparkle in his eyes, he told us of a time when some neighbor came into his grandfather's tea garden smoking a pipe and his grandfather chased the man out, not letting him live the infraction down for the next three days. In honor of that, the Huangs also start the picking season with prayers and a silent walk to the gardens for the first harvest.

True Cliff Tea (Zhen Yan) is only harvested once a year, like all tea was traditionally - before the industrial 'Nature as resource' philosophy began to motivate tea and other agriculture. This means that the families in Wuyi must earn their entire income from the output of these few weeks. This ensures focus and heart from them all. But beyond that, the Huangs have a true passion to make better and better tea, and a reverence for Tea. As the old master, Huang Xian Yi told me about the many decades when tea was sold for almost nothing - not enough to feed a family - I realized that the people who carried those stones thirty kilometers weren't economically motivated to do so. While they may have made part of their living from tea, it wasn't the reason why they were willing to go to such great lengths to honor Tea. It was because they revered these trees, and through them found heritage and culture that connected them in a living way to their forebears.

Long before others in the area, the Huangs made a decision very early on to bear the extra costs and produce all their tea organically. Of course, they then had to weed by hand, find ways of managing pests and ways of fertilizing that may not increase production as much as the chemical alternatives. "We decided that if the tea was better for people and the land we love, then it was worth the extra effort. We knew other people would care the way we do and pay a bit more for finer tea." That decision came out of a heart devoted to being a tea maker, not just making tea for money or because that is what you do - but because that is what you are, heart and soul.

From the ages of twenty to twenty-six, Huang Sheng Hui lived in the Tian Shin Monastery, studying Buddhism and volunteering as a lay novice. He had an inclination to leave home and become a monk, but he was the eldest son and his father needed him to help with the work at home. During the latter part of that period, the words that the old father used to convince his son to come back home, for me, sum up what makes the energy of Rui Quan tea different from other producers in Wuyi and other tea mountains I have been to. The old father said to his son, "Meditation and study of scriptures is good spiritual cultivation, but making tea is also spiritual cultivation."

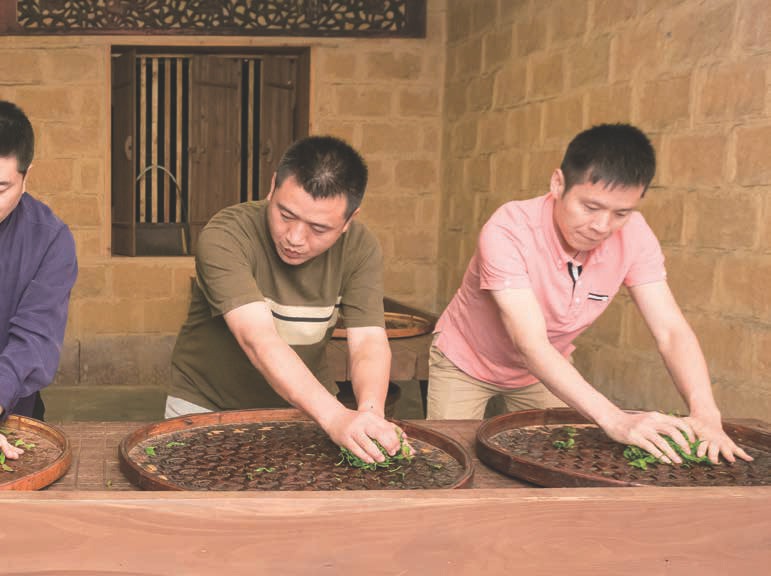

Handcrafted: Out of the passion to make finer teas as a Way (Tao) of life, the Huang's realized early on that it would have to be by hand. No machinery is as sensitive as the hands of a master, shifting and changing the processing methods based on the tea. For example, if the tea leaves have more water, the frying (sa qing) should be done with long, upward pulls that scatter the extra moisture; whereas tea from a dry season should be fried in little inward rotations that hold the leaves in the wok and preserve the water content.

Like the other families in Wuyi, the Huangs bought modern machines to produce more tea, quicker and more efficiently. In most houses, the elder masters then make a small batch of some hand-processed tea to give to important clients, good friends or government officials. Over time, this meant that the traditional processing skills would eventually not be handed down to future generations - yet another aboriginal art leaving this superficial mechanical world for some other. This would break the old master's heart, so the Huangs began increasing their production of handmade tea every year. In that way, his sons all continued to practice making tea the way they had first learned back when they still lived in the park, with a chance of one day becoming the master their father was. They eventually started making more than half their tea in this way, becoming the only family in Wuyi producing large quantities of fully hand-processed Cliff Tea.

Producing tea fully by hand in the traditional way is unheard of in the oolong world. You would be hard pressed to count a single hand's worth in the whole world. I know of only one in Taiwan, though there might be others. And even those who know how to produce tea by hand and do so, very rarely create large enough productions to share with anyone. In this way, the Huangs are doing more than just creating incredibly fine tea, produced by master hands; they are also protecting and preserving important cultural heritage.

Made in the Park: The Huangs own around fifty acres of some of the best gardens in the park, all with heirloom trees, many of which are centuries old. But they aren't the only family to have access to Zhen Yan tea. Many aboriginal families are producing True Cliff Tea. But Rui Quan is the only family producing their tea inside the park itself. In the late 1990's, when Wuyi became a UNESCO protected park, the aboriginals were relocated to a small village on the other side of the river that demarcates the national park. They were given subsidies and low-interest loans to build a small village there. They built simple, modern gray houses with shared walls along several little streets. The families then converted the first floor of their houses into tea processing facilities and they live upstairs. The Huangs also have a house in the village, where they too processed their Cliff Tea for many years.

The old master of the family, Huang Xian Yi, has often told me that moving out of the park, his home and inheritance, broke his heart in a way that it can never be healed. He said that every time he crosses the river and leaves the park, his body feels different. I asked him if the same could be said for the tea. "Of course," he exclaimed, "the energy in the leaves shifts. Also, the hike to get the leaves is already a long one and when you add the time it takes to then transport the leaves by vehicle over to the village, it can sometimes take too long, affecting the overall withering of the tea. And that is the most important stage in processing fine oolong tea." Furthermore, the small village was designed to be simple and affordable rather than architected to create the finest tea. Having no outdoor space, the tea produced there is all withered on the road, or in the adjacent parking lot, exposed to car exhaust and the dust of life traffic. Traditionally, fine Cliff Tea went through its outdoor withering on round mats suspended on long bamboo poles that allow airflow from underneath. For these and many reasons, the Huangs knew that to produce the best Cliff Tea it would have to be done in the park, as it always had been. But how? Building in the park was illegal.

With that dream as a guiding star, they never let go of the idea, saving all that they could with the hopes that such an opportunity would come. Because of their dedication to hand-processed tea and protecting cultural heritage, they began to attract true tea lovers over time, including my own master Lin Ping Xiang. People began to recognize how much heart they put into all aspects of their tea production, from caring for the trees organically to producing the tea by hand. Eventually, they achieved some renown. Saving all their money, a lifetime's worth, and working together with local and federal governments, their dreams finally came true: In the mid-2000's the Huangs were given permission to convert the only building in the park, an abandoned, run-down government office, into a tea processing museum that would protect the cultural heritage of Wuyi traditional tea processing. They spared no expense and left no detail undone, including the walls which they re-built, using the traditional mud bricks that were used to build the tea processing facilities in the old days in the park. This same mud from inside the park has an energy to it, but more importantly it allows the masters to control the humidity and temperature much more skillfully. They also installed the bamboo poles outside to wither the tea in the way it should be.

Apart from the tea processing facilities, the museum has several tea rooms to hold events, like the International Wuyi Tea Gathering we attended on our trip, a library and many local antiques. Aside from the monks of Tian Shin Monastery, Rui Quan is now the only Wuyi Cliff Tea produced inside the park itself. This makes Rui Quan tea the "Zhen Zhen Yan."

"Rui Quan" teas have been produced for more than three hundred years, though they officially branded the name in 2003. Our host, Huang Sheng Hui is the twelfth generation in a line of master tea producers. For most all of that time, the family lived inside the park in several locations, finally settling in the Water Curtain Cave (Shui Lian Dong) area where the past five generations of Huangs lived in the same large house with four wings and a courtyard in the center. When we first arrived at the Water Curtain, the whole Global Tea Hut group was breathless, and only after several full breaths came back did they realize that people once lived here. "This was someone's back yard", one guest exclaimed. The stunning escarpment is a giant brushstroke of browns, yellows and oranges that are different from the dark blue/gray of the other cliffs in the park. And from this giant cliff, a thin waterfall has ever flown, swayed by the wind back and forth like a summer curtain billowing before an open window, and then falling into a pool beneath where the Huangs once bathed in the warm seasons. The green valley and centuries-old Water Fairy (Shui Shian) trees all around made it feel as if we'd strayed into a dream.

We sat up on the ledge near the old village temple that used to be devoted to Guanyin, though the government has more recently made it into a Confucian temple. We drank tea from the old bushes growing just a few meters away, with water from the curtain itself. Transported and uplifted, everyone felt a deeper reverence for the place that made these people and this magical tea both. The park is in the Huang's blood, just as it also runs through the roots of the old trees here.

Their tea processing facilities were also located there, along the large cliff, and the ruins of it still stand. Visitors to Wuyi often put sticks between the cliff bottoms, balanced upright as prayers for healing. We all placed prayers by the old tea processing facility, hoping for healing in all our Cliff Tea, for us and those we serve. The bluff and ledge on which the old processing facility rests is called "Rui Quan" which means "Auspicious Springs", and is, of course, the inspiration for the family's brand.

The modern history of tea production in Wuyi is often sad, like much of the world's. The sons have had easier lives, but the old father has seen his share of hard times. Despite that, he is quick to smile with joy. Fortunately, Wuyi was not directly effected by WWII, as the Japanese never invaded or bombed this rural area. Most of the people I have asked about this attribute it to the protective energy of so many thousands of years of meditators, monks, hermits and other spiritual aspirants that have lived and practiced here.

In the late 1970's, the families in Wuyi were forced by the government to grow rice, and many tea trees were uprooted by officials. In the Qing Dynasty, there were more than eight hundred varietals of Cliff Tea. Over time, that number has been reduced to around fifty, many of which were lost at this time. In 1982, the government returned the tea trees to the aboriginal people, leasing the land to different families. Great councils were held to divide the old gardens amongst all the people living there based on how many relatives each had. I asked the old master if there were many arguments over who got which garden at that time. He said, "No, in those days people were used to village life and council. And while some gardens or trees were famous, all the tea was good."

Even though they began farming tea again, the government took the finished tea and paid them very moderate wages. They barely earned enough to buy clothing, tobacco, oil, soap and sundries. All of their food had to be self-cultivated, which meant that when they weren't caring for the tea gardens or processing tea, they were farming vegetables, raising pigs and doing other chores. "It didn't feel like work, though" Huang Sheng Hui says. "It felt like life. It wasn't something you had to do, but who you were. And the vegetables we grew were amazing... I still remember how delicious they were. You can't find such nutritional food nowadays."

In 1993, the old master began producing tea with real heart, and loving what he did. He began investing all his soul in making better and better tea, which he would sell in small packets to tourists for nine RMB a jin (500g in Mainland China) for his highest quality tea. He also would boil stems and some leaves and sell bowl tea to passersby for some pence. The money wasn't enough to have a savings, but they were happy living in the beautiful park, making such fine tea to share.

Huang Xian Yi (黃 賢 義) is the eleventh generation in a lineage of tea masters from Wuyi. He was born in 1949, at the birth of his nation. As a boy he hopped from stone to stone to get to school at the Tian Shin Monastery. He went on to boarding school in the local town for five days a week, but later returned home when the school closed for lack of students. He began helping his father farm vegetables and tea. In the early 1990's, he began to put his heart fully into a life of tea with an earnest desire to master all the skills needed to produce the best teas he could. He sold his teas by the packet to tourists outside his home at the Water Curtain Cave, also serving boiled bowl tea for a few pennies a bowl. After the family was moved out of the park in the late 1990's, he made a decision to move more and more into hand-processed tea, preserving the traditional tea making skills passed down so many years.

It is amazing to watch Master Huang craft tea. The young men struggle to roll the tea halfway across the mat, for example, flexing all their muscles in doing so. The old man, much smaller than them, pushes the tea across the mat with ease and grace, and without any contraction. You can see the energy moving up from the earth through his entire body. He rolls the tea with every particle of himself. And the tea he makes challenges what you thought possible.

The eldest son of the Huangs, Sheng Hui (黃 聖 輝) was born in 1973. He also grew up in the park, walking to the neighboring elementary school, which only had nine students. When he was young, his grandma would take him to all the many temples around the Wuyi area, and the boy proved to be a devout Buddhist. When he was twenty he moved into the monastery to study Buddhism and volunteer. He lived there for nearly six years before coming back home to help in the family business. He married his wife in 2000. She is related to the abbot of the Tian Shin Monastery, who asked them to take over care of their guesthouse outside the park in 2002. In that year, Sheng Hui moved with his wife and baby into the Buddhist guesthouse where they still reside today. Despite their success, Sheng Hui lives modestly, using the guest house to host friends from all over China (and now the world) every year. He loves kindness and hospitality. He is one of those magical people that make you feel special when you're around him. Like his father, he has placed Tea above all else in his life, with a devotion that is inspiring and infectious to be around. He is amongst the best tea friends I have ever made, inspiring a lot of what we do here at the center and in our travels as well.

As I talk with the Huangs each year, three recurring themes always inspire me: The first is how deeply their ancestry is rooted in the park, and how little life there was affected by the outside world. The old father laughingly relates how the people had different names for things from the outside world than what they are called by mainstream society. The son tells of how his entire school from first to fifth grades was only nine students, all of which he still knows today. You get the feeling that these are a rooted people - people who grew up with their blood and sweat irrigating the land their ancestors also bled and sweat on, with lives rooted in a rich culture and calendar of holidays, harvests, weddings and funerals that connect them in a tangible way to their lineage. With sparkling eyes, Huang Sheng Hui told me that, "In those days, wedding feasts would go on for seven days, bringing the whole village together. These days, you just eat one meal for a few hours."

The second theme that threads through the fabric of all our conversations, leaving me embroidered with Tea spirit, is the influence of the park itself. I love the stories of when father or sons were boys, leaping over rocks on the way to school, catching fish with their hands, or occasionally meeting hermits or monks meditating in caves. They told me of a time the whole village saw an immortal walking across the tops of the trees, or the father and his young friends coming upon a cave inhabited by an old hermit that was glowing with an otherworldly light. Life inside the park was even more beautiful than a walk through its glorious paths can now reveal glimpses of. And one can understand the broken-hearted sadness that comes with being moved out, not to mention the end of the villages and traditional culture that surrounded them. But the grief has not overwhelmed the Huangs; they still treat you like you're a village neighbor, and they still carry their culture and heritage in their hearts, shaking, frying and rolling them into their tea.

The last, and most glorious, topic we always discuss is Tea itself. I always leave grateful to tears that I have had the fortune to meet in this life people who revere and honor Tea as more than just a commodity - as a way of life, a sacred plant and a rich and deep spiritual culture. The Huangs truly love Tea. And all the Wuyi stories, from the legends that surround the varietals' names to the more personal stories like the one I just told about the old grandfather scolding his neighbor for three days because he smoked around the trees - all of it leaves you humbled. As I walk through the park, I see and feel the terraces as altars and the trees as worshipped saints. And all that reverence isn't just fancy talk to sell their tea; the Huangs have gone through great hardship and put forth constant, diligent hard work to produce the best tea they can, sparing no expense in time or money to improve what they do for its own sake.

In the late 1990's, the Huangs met Master Lin Ping Xiang, forming a deep and lasting friendship that has also led us to them. It says a lot when such a great teacher supports everything you do unabashedly, especially someone with as much integrity as Master Lin. Over time, the care and love the Huangs have put into their tea have brought them abundance and success. They have come a long way from selling bowls of boiled tea to passersby for a few cents. When the gardens were divided up in 1982, the Huangs owned around five acres of trees. They have since increased their stewardship to roughly fifty acres, with some of the brightest and best teas in the park amongst them.

When I asked them about their future goals both father and son said that they hope to pass on these traditions to the next generation. Currently, all three of the sons are mastering different aspects of the business. The eldest son, our host Huang Sheng Hui, is in charge of customer service and marketing. His time in the monastery shows in his natural ability to love kindness and deal with others. The second brother is working directly with the old master to inherit the processing skills. The father said his skills are good enough to make excellent tea. He is now teaching him all that is needed to manage the estate and the workers, and about the changes in weather over long periods of time. He said that they employ based on a meritocracy: "When people work hard and get better at tea processing, we reward them accordingly." The third, youngest son is the accountant for the family. And all three have children, so there is hope for traditional, hand-processed Cliff Tea.

Having traveled with us in spirit, we hope that you recognize how precious this month's tea is: crafted from old trees in one of the most idyllic spots for tea in the world and processed by the hands of the eleventh and twelfth generation of master tea producers. And not just great tea makers or even great people, the Huangs are also our great friends.