|

|

The vessel that heats water for tea is just as important as the source and storage of the water itself. Each kind of kettle has its own energy, and different kinds of kettles may also be better for different kinds of teas. The ideal is to have a variety of kettles, becoming sensitive to the relationships different teas have to different kinds of water and heating methodologies.

Water preparation is paramount to developing mastery in tea art. Most of what goes into a cup of tea is water; and for that reason, choosing good mountain spring water and preparing it properly are the most influential ways to improve one's tea. All too often, we have seen great teas disrespected by poor water or inadequate kettles. Some tea houses mistakenly devote their time to seeking out and providing high-quality teas, which then never flourish because the water and kettles they supply reduces the tea to average quality. Similarly, many tea lovers never spend the money or time to research a good kettle, and/ or find the best source of water, and consequently aren't getting as much out of their tea as they could. When you realize just how tremendous an impact a good kettle can make, and that you technically only need to buy one to last you for the rest of your life - enhancing all the tea you'll ever prepare - finding the right one becomes paramount.

But just what is the "right one"? That is where the whole idea of recommending teaware and sharing one's experience gets tricky. First and foremost, it is important to remember that all you ever need to explore and share tea is leaves, water and heat. The best tea is made with love. It is the heart of the host and guest that make a session transformational, not the teaware. And yet, there is a refinement that can be pursued in the cultivation of a tea practice. In exploring the different kinds of kettles with us, please don't feel that there is ever a need to buy expensive teaware in order to make fine tea, or that "real" Chajin have such wares. The cost of silver or iron kettles has changed over the centuries they have been made based on the arbitrary whims of the market. Actually, they are priceless, much like Tea Herself. Choose the kettle(s) that work for you on all levels: functionally making nice tea, is aesthetically pleasing to you and affordable to your budget.

So much of tea preparation is alchemical and elemental. The ancient Daoist mendicants utilized tea as a part of their spiritual regimen, leading to the transmutation of the immortalizing "Morning Dew (gan lu, 甘露). The combination of the elements isn't just about the spiritual, internal aspect of Tea either; it also leads to the most flavorful, aromatic and rewarding cup of tea. Lu Yu himself carved the trigrams that represent the elements onto his teaware, recognizing the importance they play in a life of tea. Proper preparation is everything in gongfu tea, which refers to something done with deep skill or disciplined mastery. And even in simple bowl tea, the elements are there. The five elements - water, fire, metal, wood and earth - are all important in tea, as is the way they dance and move amongst each other. Exploring each of them, and their complicated roles in tea preparation is rewarding, indeed. For now, let us begin by touching on the most sensitive of all the elements, metal, which enters the art of tea through the kettle, of course.

Many ancient masters thought that metal was the element that could affect tea the most. Some even rejected the use of all metal in tea brewing, since the Qi is potentially harmful to the leaves, which are the wood element (axe slices the tree). These old masters argued that the flavors of metal are strong and overpowering, are able to drastically alter water and tea liquor both, as well as change the Qi. We also have found that the flavor, aroma and Qi of a tea are greatly influenced by the quality of metal used, and which step in the session the tea or water contacts the metal. Just as metal conducts electricity, so also does it conduct Qi. Perhaps more than the other four elements, metal has the potential to make or break a tea session. It is, therefore, important that all the metal we use be high-quality. If we don't have access to fine metal, then we might consider removing all metal from our tea brewing, as many tea masters have suggested. And yet, without metal, one is missing one of the elements that make tea so naturally holistic.

Aside from quality, it is important to know where in the tea brewing process metal can be used. We have found that the only ideal place to allow the element of metal to enter the tea ceremony is between the fire and water. Because fire and water both are stronger than metal, it overpowers neither of them and buffers their relationship as well. For that reason, we very rarely use a metal teapot, strainer or other implements at the Hut. (We even use horn puerh knives rather than the more common metal ones.)

Since ancient times, tea masters have agreed that silver was the ultimate refinement in tea preparation. We have had the fortune to try water prepared in a solid gold kettle as well. While the water was slightly better than that prepared in silver, it was not worth the extreme difference in price. Furthermore, such gold kettles are extremely rare. For most all of us, silver is therefore a much better option. In his book The Classics of Tea (Cha Jing), Lu Yu said:

For the best and longest use, the kettle should be made of silver, yielding the purest tea. Silver is somewhat extravagant, but when beauty is the standard, silver is the paragon of beauty. Likewise, when purity is the standard, silver yields such purity. Consequently, for constancy, longterm use and supreme quality one always resorts to silver.

Even then, tea masters understood the magical effects that silver has on water, as well as the aesthetic grace that a beautiful silver kettle brings to the tea table.

Of course, there are many qualities of silver, ranging from the silver-plated kettles of Japan and England to the solid, hand-crafted antique pieces made in Japan. There are also some modern, mold-cast kettles produced in Taiwan and Japan using extremely pure silver. Of these, we have found the traditional handmade Japanese kettles to be the best choice.

The Japanese were masters at every craft they explored, and silver was no exception. The silver mined in Japan was unusually pure to begin with. The masters then further refined it through secret smelting and folding techniques passed on from teacher to student. The folding of the silver was perhaps similar to the steel-forging techniques used to create Japanese swords, also masterpieces that are considered by historians to be of a higher caliber than contemporary weaponry. The Japanese silver exceeds Sterling in purity, the latter being around 92.5% while most of the Japanese kettles have a silver content of 95% or more.

The Japanese made their kettles from a single sheet of this pure silver. Very few of them were cast in clay molds that were only used once. Almost all of them were hand-hammered - slowly formed into bright and functional masterpieces. When you look at them up close and notice all the amazing work that went into hammering the body, joining the spout and handle - often with handmade pins or joints - they are truly awe-inspiring. Some of them took weeks to create and it is perhaps only the Japanese devotion to perfection and mastery that could have focused so much time and energy into a craft, as they did with most all aspects of their lives.

The kettles come in wooden boxes that usually give the artist's name, sometimes the date and even the name of the kettle itself if it was given one. There are nickel/tin kettles that are silver plated, and some student-made pieces that are much cheaper than the masterpieces. The pure-silver kettles have a mark on the bottom signifying their quality level, an important characteristic to look for. It is crucial to be careful with all antiques. Seek out the guidance of an expert when purchasing an antique silver kettle, especially since they are so expensive.

The purity of the silver cleans the water, making it brighter and sweeter. We have experimented in several ways over the years, including several comparisons using people who do not drink tea and have no particular sensitivity or refined palate. One experiment was to line up four identical porcelain cups and ask the participants if they found any of the waters to be "different." All four waters were room temperature, and three of them had been poured from the same clay kettle, while one had sat for about ten minutes in a Japanese pure-silver kettle. We conducted the experiment about seven times, each time with 3-4 different participants, none of which were tea lovers or had any experience with silver. We found that an overwhelming 96% of the time, the participants could pin-point the water that had been in the silver kettle. We then trained them, explaining the experiment and pointing out some of the characteristics of the water that had been in contact with the silver, at which point they could find the water without fail. And this was unheated water that had merely sat in the kettle for some time!

We have also experimented by taking a pure-silver kettle around to various tea lovers' houses and shops - all of whom were unfamiliar with such silver kettles. We then asked them to prepare tea in their usual way, using all their own teaware, a tea they are very familiar with, as well as the water that they generally use. The only difference was that we substituted the pure-silver kettle for the one they ordinarily use. We then asked them to report any differences they experienced. All fifteen of the tea lovers we tried this with, unanimously agreed that the tea was better, brighter, sweeter and had a better aftertaste. About half also noticed that the tea was more patient.

The water from the silver kettle even looks a bit different. If it is put in glass, side-by-side with normal water, it appears slightly shinier, especially at the top. The real difference, however, is in the flavor and Qi. The silver-induced water is sweeter, softer and smoother in the mouth. It tastes "purified", for lack of a better word. We have also found that teas prepared with this water are always more patient, yielding almost twice as many steepings.

The Qi of the water prepared in a pure-silver kettle is also light, smooth and refined. It rises up, making teas shine, and causes the vibrations and flow of Qi to become softer and smoother. It is especially suitable for green, white, yellow and light oolongs, refreshing them in an amazing way. The water seems to rise up, with a buoyant Qi that makes one feel as if floating.

There is a jeweler's cloth that polishes silver nicely, though you should only use this on the outside of the kettle. Otherwise, it is better to leave the cleaning to experts, making sure your kettle has been scoured before you purchase it. It is also helpful to dry it, wrap it in cotton and return it to the box after each use, in order to prevent oxidation and reduce the frequency one needs to polish it.

The effects of silver on water for tea are really amazing, and worth looking into, if you can find the chance to save up for a kettle. We have found that the value of the kettles continually appreciates, making them a solid investment as well. Tasting the smooth and sweet water, and the magical way the Qi of the silver subtly transforms a familiar tea into something exquisite, one can't help but feel a sense of awe for the mountain smiths who hammered and forged these exquisite pieces.

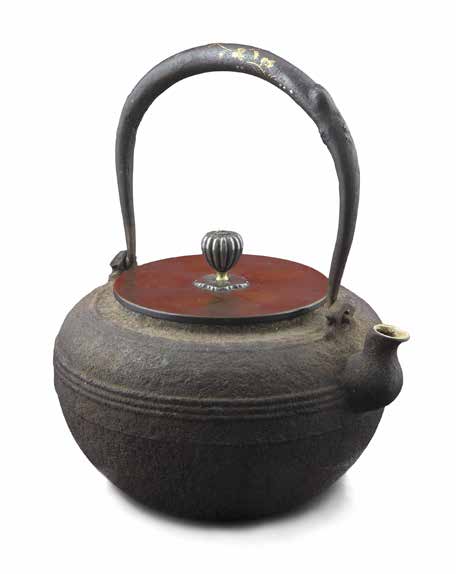

Antique iron tetsubin are a great addition to any tea lover's collection. They can be anywhere from decades to centuries old. Most of the ones on the market in Asia date from 1900 to the start of WWII. They are cast in an array of designs including bamboo, various natural textures, plums, fish, etc. and the higher-quality ones are often inlaid with gold and silver on the handle, knob or even sometimes on the body. The prices of such kettles also vary tremendously, and part of this is due to the artist or "house" that made them. Of course, handcrafted kettles that were made by famous smiths will be worth large sums of money. It is still possible, however, to find a nice tetsubin from this era at a reasonable price.

When buying an iron tetsubin, there are two things to keep in mind: aesthetic appeal and water quality. Of course we want a kettle that is attractive and lends itself to the tea ceremonies we are having. For this aspect, there is no set of guidelines or advice, since each of us must use our own discrimination.

The function, then, is perhaps of greater importance than who made the kettle or even how nice it looks. It should heat up nicely, pour smoothly and of course not leak anywhere, which some of the antiques do unfortunately. If the pot has sat unused on a shelf, the inside will be rusted in hues of orange and brown. This isn't ideal. One should instead look for a kettle that has what the Japanese call "fur", a layer of whitish-yellow minerals on the inside. This is a sign that the kettle was used in conjunction with mountain spring water for some time, and these mineral deposits enhance the water greatly. It is difficult to find one used so much that it is completely covered with "fur", but try to find one that has at least been used regularly since it was made. By using mountain spring water yourself, you will also contribute to this build-up of mineral deposits. Some of the newer tetsubins have enamel coatings on the inside, which means that they are made to be teapots, not kettles. It is much better to use the antique, cast-iron ones, which are porous and absorb minerals. Antique cast iron tetsubins are also made of the famous "pig iron" that influences water for tea.

We have found that, because of the differences in the original iron, coupled with the water that was boiled in it over time, each antique kettle has its own unique flavor. No two are alike. There are those with similarities, but every antique tetsubin adds its own flavor to the water. There are of course, generalities that are common to all good iron kettles: they all impart a sweetness to the water, bringing depth and more flavors. For that reason, they are best suited for brewing heavily roasted teas, aged teas, puerh and red teas. These teas are already rich, so the added depth - even the extra flavor a kettle may have - only make the tea more complex, varied, deep and rich. We have found that the water brewed in iron tetsubins has a heavier mineral content and an earthy Qi. It brings to the water or tea a depth and richness, with a slightly sweet aftertaste depending on the kettle. Because many of these teas are as much or more about the Qi as they are about flavor and aroma, and because they already have deep, rich, earthy flavors, an iron tetsubin really enhances them and brings everything to a deeper and richer level than otherwise possible. As the Qi of the water moves downward and is loaded with earth and Yin, this kind of kettle isn't as nice for oolong, green, white or other lighter teas - often overpowering their delicateness. There are exceptions to this, though, as some iron kettles are lighter and sweeter, more like silver.

One great thing about iron kettles is that they can be used in conjunction with hardwood charcoal. They are strong and durable and respond extremely well to charcoal. The water cooked on such charcoal always maintains a higher temperature, steams more and brings depth to the tea. The temperature and energy of charcoal is very different from hotplates. Most masters, ancient and modern, agree that in general, higher-quality teas respond better to higher temperatures, while lower-quality teas are better brewed at lower temperatures. The obvious reason for this is that more of the essence of the leaves is released when using higher temperatures. No electric heater can ever get to the depth of hardwood charcoal. It brings out many deeper, subtler levels from a tea, rewarding us with a deeper sense of the tea's essence. Try using hardwood charcoal with your higher-quality teas and you'll find a whole new world waiting for you.

In order to truly shine, these iron tetsubins also really need the added heat. We have found that when we use a hotplate in conjunction with an iron kettle, the effect is not nearly as nice and we feel like we would have been better off using silver. For the minerals and earthy Qi to really shine, it would seem that these old iron kettles need that extra bit of heat from a natural fire. They were created to be heated in that way. The fire element is purer in a charcoal fire, and the heat deeper.

After trying the water from several iron kettles and choosing one, there are some important things to remember in raising your antique tetsubin. Since it is porous it is important that you continue to fill it with good water. If it has a mineral layer from decades of spring water, you shouldn't continuously fill it with low-quality water. By adding spring water, you will further its seasoning and it will get better and better with each use. Also, iron tetsubins cannot be used in conjunction with gas stoves. The flames will crack the bottom of the tetsubin over time. If it is necessary to use a gas stove, you could buy a clay disk sold throughout Asia. The disk distributes the gas flames through pores and prevents them from harming the bottom of your tetsubin.

Finally, to prevent rust, it is important that you keep your tetsubin dry. For that reason, you must "roast it dry" after every use. This is done simply by emptying out all the remaining water and returning it to the heat source - lower it if possible - and monitoring the inside until the water has evaporated. When using a hotplate, we just turn it off and place the iron pot on top. As the hotplate cools down, there will still be enough heat to evaporate the water inside. This is done with the lid off, but the lid should be returned once the kettle cools down. If you prefer heavily-roasted tea or aged puerh, an antique tetsubin will greatly improve your tea. Aside from the depth in flavor and rich, earthy Qi, an antique tetsubin has a certain aesthetic that is appealing, especially when it's resting above some charcoal. Listening to the "wind soughing the pines" and feeling the gentle heat of the charcoal is often a worthwhile enough reason to appreciate iron tetsubins.

This is Wu De's teacher, Master Lin Ping Xiang's favorite way of making water. He prefers the high-grade stainless steel kettles/pans made in Germany for chefs. These pans or kettles are made of high-grade stainless steel and aluminum folds, which ensures an even temperature all throughout the kettle or pan. Since the temperature is perfectly distributed to a decimal of a degree, the bubbles rise in even strings without ever colliding with one another. This results in very smooth and even water that comes to a boil quick and strong, and brings a light briskness that will enhance and bring out the best in a fine tea. Master Linn suggests buying kettles by the company Henkel, famous for their steel technology.

Master Lin boils the water in a stainless steel kettle and then pours it into a smaller Yixing purple-sand kettle that sits by him on the table, boiling on charcoal or an alcohol stove. An Yixing kettle is perfect for gongfu tea, bringing the same smooth, roundedness to the tea that a good pot can. You may find that you will need a cha tong (tea assistant) to make water for tea in this way, but the water will be especially vibrant and bring out a very smooth and fine cup. This is an excellent way to brew gongfu tea. Each and every cup will shine brightly with such discipline in water and fire.

If you find a good stainless steel kettle, you can also use it without a smaller Yixing kettle. Stainless steel is nice as it can be used for a long time, and on any kind of burner, including charcoal. There are many grades of stainless steel, just as with cooking pots/pans, so it may be worth doing some research and /or experimentation if possible.

When we have to, we use a plug-in electric kettle to boil water. For some reason, we find the stainless steel kettles made by Phillips to make nicer water for tea than the other brands available in Taiwan. This probably has to do with the quality of the stainless steel. There may be nicer ones out there. We must admit that this is our least favorite option when it comes to kettles. Many of these products use induction heat, which is a bit like microwaving food.

Glass kettles are great! As long as the glass was tempered and has a protective coating on the bottom, they can be used for a long time, cleaned easily and be surprisingly sturdy. It is better to have a kettle made completely of glass rather than the ones that are metal on the bottom, as it is often low-quality metal like cheap stainless steel, aluminum or even tin. Glass kettles let one watch the water, recognize the bubbles and temperature, and learn about the changes in the water as it heats up. Many of us used a glass kettle for our first few years of tea brewing. Watching the bubbles is the easiest way to get a feel for the water temperature. Also, after time, you can then compare the temperature you know from the size of the bubbles to the vibration, sound and other methods. The water is also pretty neutral in a glass kettle, which is good for tasting new water sources or storage methods, though you lose the enhancement other kinds of kettles offer.

Clay pots can be superb or can ruin the water. One should be careful to choose a kettle that is made from good quality, natural stoneware. It is better if the clay was refined naturally without any manmade additives. Some masters suggest that volcanic ores mixed into clay for kettles makes them produce cleaner, better water. Such clays conduct heat better. This is important, as mentioned above, because it is better to heat the water quickly so that the energy isn't changed.

Clay kettles are much cheaper than silver or cast iron kettles. A good-quality stoneware kettle is often a nice improvement after learning from your trusty old glass one. You may notice right away that the water is smoother and deeper. Clay kettles also force you to use your sense of touch and hearing to gauge water temperature, which isn't as easy as looking at the bubbles. However, the problem with glass and clay kettles is that you lose the element of metal, so your tea sessions are lacking one of the five elements. Having all five elements and learning how they interact with each other to refine one's tea is an ancient and beautiful art. Of course, this isn't essential, but the quality of one's tea will be affected in every way: flavor, aroma and Qi. In fact, the best clay kettles will have a high iron content in the clay used to make them, which conducts and maintains heat better - so they heat up faster and stay hot longer.

There are two tiers of clay kettles that one can find: The first kind is more mass-produced, and comes in a range of qualities. We usually recommend those made out of volcanic ore, and then mass-produced here in Taiwan by a company called Lin's. Many of you have started your tea journey with these kettles. They are affordable, and though they are made in larger quantities, each one is trimmed and finished by hand. They look nice and make very decent water for tea. The red clay inside is high in iron and therefore closer to a metal kettle. What's more, they can be put on infrared heaters, hot plates, gas and even charcoal due to the lining that is painted onto the bottom of these kettles. This makes them extremely convenient for anyone. Their only setback is that they do not hold temperature at all, which kind of forces you to have an alcohol stove, a candle or some other kind of burner right next to you as you are preparing tea. These kettles will only stay hot for a minute or two, so they need constant heat.

The next step up from Lin's clay kettles are those that are handmade by masters like Chen Qi Nan or Deng Ding Sou (both of which we have covered in this magazine). Their kettles are master-produced, and by people who love tea and brew it every day. Each one is unique, with an exquisite aesthetic and innovative designs, like catches for the lids so they won't ever drop off. They also test and retest the minerals/ores they add to their clay to make better and better water for tea. Since masters like this have been drinking tea for decades, they are often very skilled at making teaware that enhances the water, the tea and the experience through the art they bring to the tea table. We would also like to acknowledge and fully recommend the kettle/brazier sets made by our dear brother Petr Novak, who many of you have met in these pages or in person. His girlfriend, Mirka (who we'll write about soon), makes braziers and he makes the kettles.

There are also traditional side-handle kettles that have been used for gongfu tea these last few centuries. The four treasures of gongfu tea are an Yixing purple-sand pot, porcelain cups, a tea boat and a Mulberry Creek stove/ kettle. These white clay stoves and kettle sets come from Chao Zhou. Originally, the clay came from a creek by this name, though potters there have used all kinds of local clay for hundreds of years. The braziers and side-handle pots from this area make nice water for tea. You can find antique and modern ones, as well as Japanese copies. These days, they also make the stove sets out of red clay, but we think that such clay doesn't make as nice of water as the white style (though still not terrible). The drawback of such sets is that they rarely make the side-handle left-handed, and as you learned in our series on the Five Basics of Tea Brewing, in this tradition we hold the kettle in the offhand to promote a smoother, more fluent brewing. Our solution when we want to brew gongfu tea in the most traditional of ways is to use an antique Mulberry Creek stove with a left-handed kettle Petr Novak made for us.

水 火 相 遇 只 為 茶