|

|

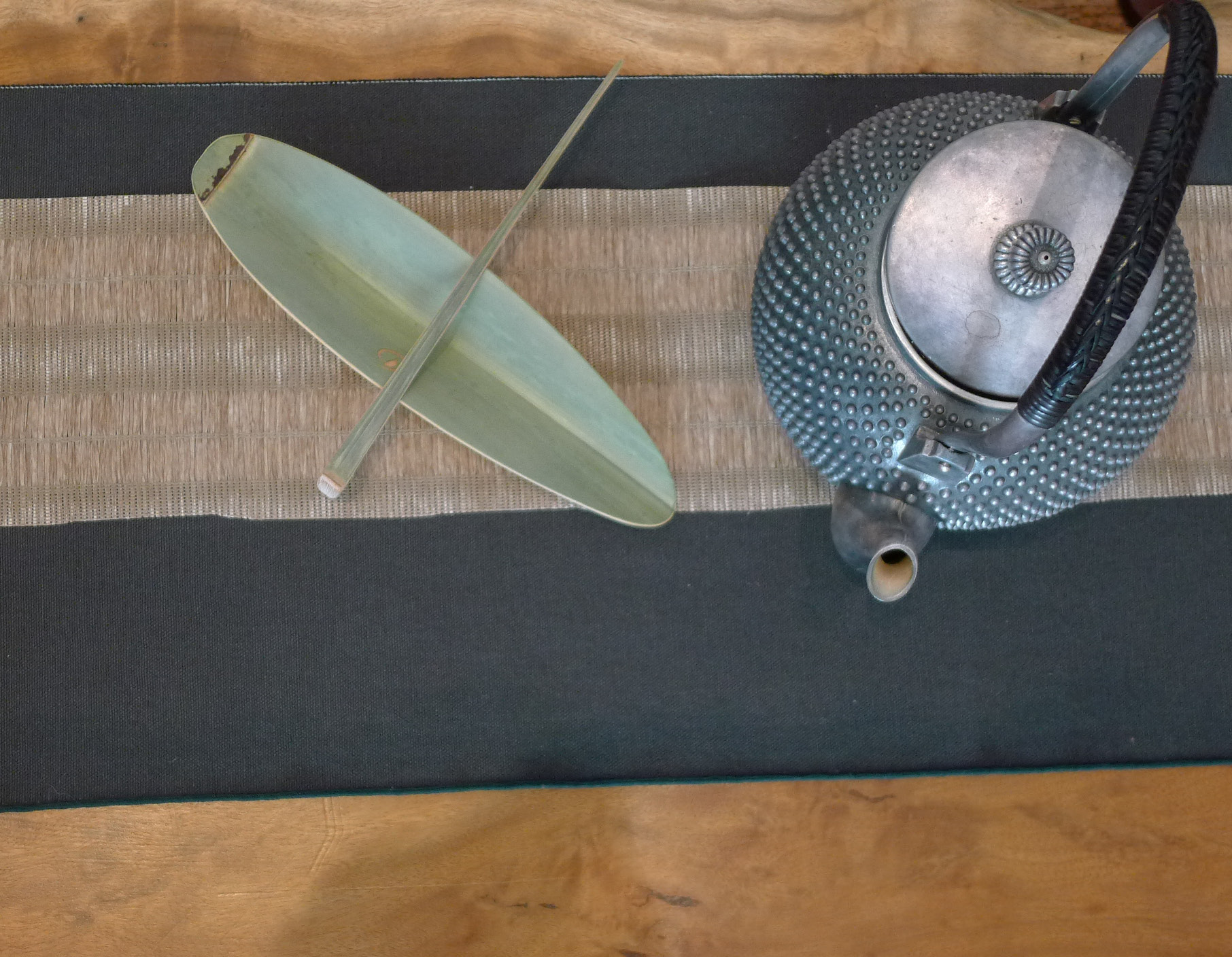

For hundreds of years teaware has been the principal method and passage through which the art of tea is expressed. The vast array of cups, pots, decanters, kettles and utensils has spawned thousands of artists, small and large, using many different media to capture their understanding of tea. From Calligraphy to painting, ceramics to metallurgy, artists have found ways to enhance the beauty of the tea ceremony.

In the Tang Dynasty, tea masters like Lu Yu favored green/blue celadon because it highlighted the natural brightness and verdure of their boiled liquor. In the Song age, teaists switched to darker brown or black bowls, which brought elegance to the green of their whisked teas; and in the Ming, when tea was steeped whole-leaf, as it is today, there was a return to porcelain cups, ever smaller and thinner, which enhanced the appearance, aroma and texture of the liquor. This vast tradition need not be at odds with Cha Dao, either. In fact, the art of tea can, and does, capture the essence of the Dao and express what could otherwise not be said, even in its more physical aspect as teaware.

And if teaware be true teaware, in this pure sense of art as transcendence, beyond form, then the viewer finds within the piece symbols that help him or her connect to, interpret or even transcend the ordinary world. In that way, our teaware and the way we arrange it might be thought of as a Mandala, which the Hindus and Tibetans define as any kind of geometric pattern that expresses an aspect or the totality of the cosmos itself, a symbolic meditation of transcendence. They also taught that objects of beauty could be great encouragement for spiritual development as long as they were used and appreciated without desire and craving. Perhaps this is what Lu Yu meant by devoting so much time to the proper creation, organization and expression of one's tea set; what the Buddhists in China and Japan later formed into the tea ceremony: its tea houses, paintings and flowers; and even what we may achieve today with the organization of our own tea sets, as expressions of our own inner nature.

The ancient Daoist sages lived simple, clean and pure lives. In their forest hermitages they practiced meditation, Qi Gong, and other methods of connecting to the Dao, including tea. In such an environment, the simplicity of bowls and hot water is enough - the pure mountain water and the essence of the Leaf were sufficient for people as sensitive as they were. Many tea sages and tea ceremonies in the modern world could be equally simple, though for some of us calming down and finding that connection to Nature beyond ourselves is difficult. Beyond just satisfying the collector's passion in us, teaware can improve our ability to relax, and help inspire our connection to our tea ceremonies. When we are in a beautiful setting that inspires calm, it will be easier to find the quiet place that Cha Dao flourishes in. Some might argue that the unassuming practice of the ancient tea sages better exemplifies ideals like renunciation and purity of mind, but we think that like all ideals, these take place on the inside. One can be attached and affected as much by a worthless stone as one can by a solid gold throne. The simplicity, renunciation and even unaffectedness must all take place within the breast of the person walking the road. If calmness, presence or renunciation are only external symbols, they are as hollow as a rich man's outer garbs meant to distinguish him from others. There is an ancient Chinese proverb that says "it is easy to be a sage in the peace of the mountains, more difficult in the city; while the deepest of saints can live unaffected in the palace."

Finding teaware that improves the sensations, flavors and aromas of our teas will help inspire us to delve deeper into the world of tea and tea culture. Many of our cups and pots will become like brothers, supporting us as we journey through tea. Our love for them can help connect us to the ceremony, igniting the understanding, connection and even transcendence of the ordinary moment just as well as the leaves themselves can. Our most prized possessions are the different teaware, and just by looking on them we find an expression of the calm joy we are sometimes able to find in tea. They are a representation of the silence and peace we find each day in the tea room, and sometimes just in handling one of our pots we can catch a glimpses of that energy.

As we have discussed elsewhere, we believe that the worlds of art and spirit have always been aligned, and though art is capable of expressing a terrific variety of meanings, within that list is the articulation of spiritual principles and experiences that are otherwise ineffable. And though art, even at its best, can never be equal to the experience of being with tea, it can help those who have had such experiences to rekindle them, not only by inspiring them to have more and varied tea sessions, but also by relaxing and connecting their spirits to the ceremony itself. Grasping in pleasure a Qing Dynasty cup - knowing its energy is stronger, the flavors of the liquor within more effervescent and joyous - this all helps increase the degree to which one participates in the tea ceremony, and that is what Cha Dao is all about. The more we participate and involve ourselves in our tea, the more it consumes the moment. We find ourselves emptied, lost in a blissful stillness. Through that, transcendental wisdom is possible.

Most tea lovers find that as their experience, discrimination and understanding of tea grow, they invariably start leaning more towards simplicity and function. Teaware becomes a matter of which cup, pot, kettle, etc. can enhance the flavor, texture or aroma of their teas - which are also becoming more refined, rare and often expensive. Of course no amount of function can outshine the skill and focus of the person through which the ceremony flows. Tea brewed ever-so-simply by a master will still be more delicious than that brewed by a beginner with the best of teaware. The conduit through which the water is held, poured, steeped, poured again and served is the most important part of the ceremony in every possible way. After all, it isn't the cup experiencing the tea; the pot doesn't pour itself and no amount of silver can gather and carry the mountain water that will be heated in its kettle. Understanding the human role in the Way of Tea is important if one is to progress, and in order to do so there must be a balance between the aesthetic and functional sophistication of the ceremony and the teaware we use in it.

The role aesthetics play in the enhancement of tea, both in flavor and in the experience as a whole, should not be underestimated. Even if one's taste remains simple, one shouldn't ignore the influence beauty has on the most important element of the tea ceremony, which contrary to the obvious is not the Leaf, but the person. Arranging the teaware, flowers, cushions and artwork of the tea space are all aspects of the expression that has ever made tea an art form. Not only do they allow for creativity and intuition, they create an environment of comfort and calm relaxation. The best teahouses, tearooms or even tea spaces in a house are the ones that immediately relax you as soon as you arrive. Even before the tea is served, one already feels outside the busy flow of the ordinary world, comfortable and ready to enjoy. This will directly affect the experience of the tea itself. It is a well-known fact that different people are all bound to taste, smell and feel a variety of different experiences when drinking the same tea - as even a cursory survey of tea reviews will demonstrate - but even our own experiences change over time and space. Why then is the same book so much better when read on a vacation at the beach? Why do restaurants devote as much attention to ambience as they do to the menu?

Learning about the various roles that teaware plays in the creation of the best cup is exciting and adds to the passion of tea. Tasting the water heated in different kettles, for example, is so insightful and often improves 21 the way tea is made thereafter. It is, nonetheless, important to maintain a balance between the teaware that will improve the ceremony functionally and that which will inspire the one making the tea aesthetically.

The process of creating the tea space and ceremony are very personal and the aesthetic design need not follow any other pattern than the one that will motivate the person who brews the tea - he or she is the master in that space, and unless it is a tea house with a steady stream of guests, then his or her feelings and intuitions are the only ones that really matter. A teapot with excellent function that doesn't at all inspire one may not be as good of a choice as one that functions a little bit worse, but is gorgeous. Again, balance is the ideal. In speaking about how the ambience of a tea session can at least result in quiet, deep relaxation and at best spiritual change or transcendence, John Blofeld remarked in his own book on tea that it was no wonder the Zen masters always ended conversations with tea, or answered particularly abstruse questions with "Have a cup of tea":

"On discovering that tea fosters the special. attitudes involved in following the Way, we shall want our tea sessions, whether solitary or in company, to be set refreshingly apart from more humdrum activities. Since appropriate objects, surroundings and atmosphere all help emphasize that feeling of withdrawal into a world of beauty, some expenditure of time, thought and money on collecting a heart-satisfying set of tea-things would seem to be exceedingly worthwhile."

He then goes on to say that the great Tang and Song tea poems are indebted to the surroundings and ambience those ancient tea sages traveled to in order to enjoy tea; and we also can achieve that by occasionally "choosing an ambience of pine trees, curious rock formations, mountain streams, sparkling sunshine, sunset clouds or moonlight", conjuring the same poetic atmosphere of lost ages. More than any other topic, Lu Yu also constantly reminds us to 'spice up' our tea sessions and life with harmonious decoration. As Francis Ross Carpenter says in the introduction to his English translation of Lu Yu, "The environment, the preparation, the ingredients, the tea itself, the tea bowl and the rest of the equipage must have an inner harmony expressed in the outward form."

Achieving harmony without helps foster harmony within, but we must never lose touch with the beings at the center of the tea session - the people here, host and guests, are most essential. Even within the preparation of tea itself, so much is dependent upon the energy of the one doing the brewing. If they are cheap and focused on getting a lot for a little, if they are a businessman focused on selling tea, or if they are rich and trying to show off their Ming Dynasty teapot, all of these factors will show in the tea ceremony, resulting in a different cup. There is no scientific objectivity in the world of art, only taste. There are those that write books on form and function, conduct experiments on water temperature and get busy recording notebooks full of tea reviews, but as such they will never progress to the level of artist or master - a level based not on the intellect but on intuition. Measuring, analysis and recording data play no part in experiential growth. One cannot record data and fully experience at the same time. Anyone who has experienced trying to review a tea, with written notes and all they incur, has already recognized the difference between these sessions and the more relaxing, personal ones. And anyone who has ever meditated or sought connection through calm knows the importance of shutting off the mind and its internal dialogue.

True enjoyment must be just that. This is why tea is made "gong fu", because it is a skill, an intuitive mastery. Cha Dao must be free and loose, open to exploration and responsive to the idiosyncrasy of every beautiful moment. And there is much to be said about brewing with a clay kettle rather than a plastic one, a beautiful Qing Dynasty cup rather than a cheap one; it's not just the ware itself, but also the fact that the one brewing isn't reading a digital temperature on his or her kettle, analyzing the ratio of leaves to pot size, etc. - he or she is intuitively dancing a flutter of leaves from the scoop to the pot, gauging the water temperature with a gentle touch, and steeping with all the relaxation of the timer built in his or her heart. Does that sound corny? Perhaps it is, but after enough tea houses, shops, teachers and enough sessions, most people would agree that the best cups they ever had were poured by people such as this. In the hands of an artist, even the simplest lump of charcoal and torn cardboard can become a masterpiece; likewise, a cup of tea brewed by the hands of a master can hold worlds of flavor, aroma and even peace just over the cusp of its rim...