|

|

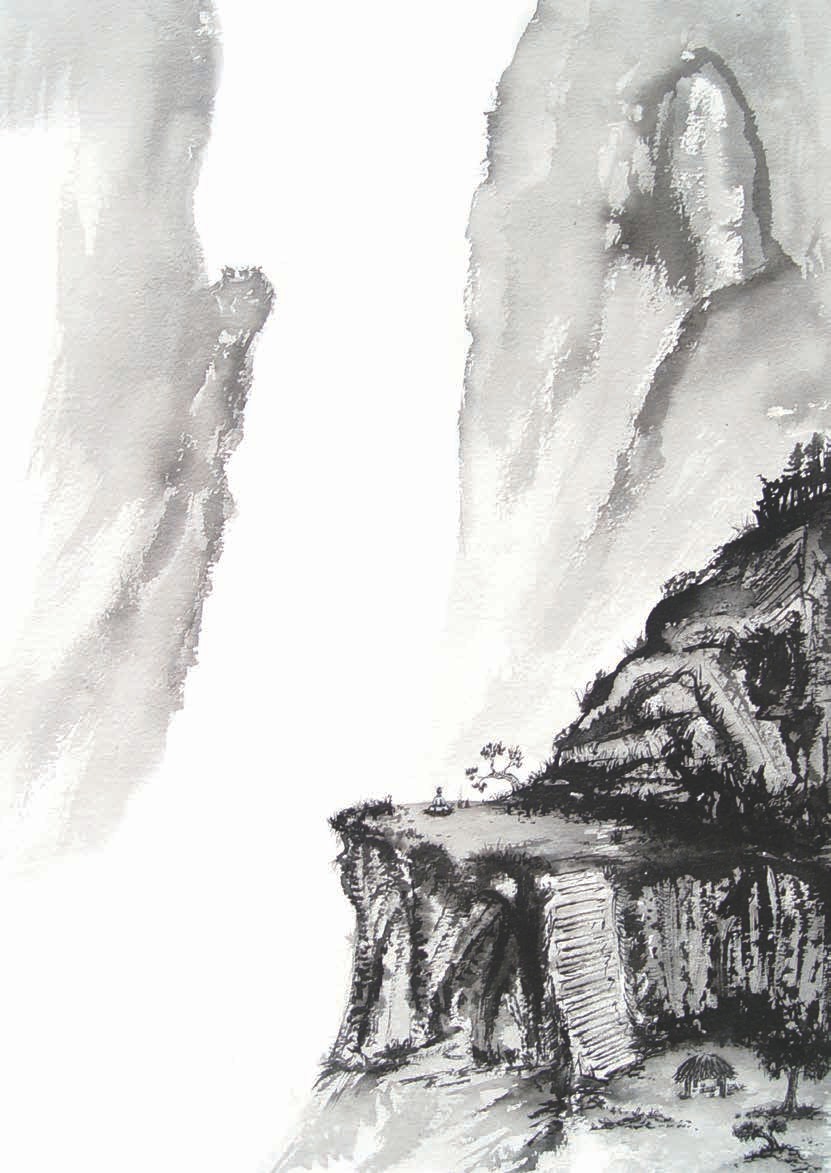

The Zen circle, or "enshu", is a loop from the gross to the subtle, and back again to the gross - like the orbiting monks who circumambulate the center of the meditation hall to allow a similar, though internal, circulation to return to their legs. We must learn to quiet the outside and return to the softness that is the chewy center of our beings. The Zen painter-monk Sengai once drew an Enshu and wrote calligraphy next to it that said, "Eat this and have some tea!"

As we shift focus from doing to just being, the world naturally turns inward. It requires no effort on our part; it's as natural as the flow of water downhill. When distractions are shut off, and outer quietude cultivated, stillness just happens. Even the most silted, muddy water clarifies itself when it is tranquil - all the more the vast depths of the lake, ever unruffled by the worldly breezes that ripple its surface.

For stillness to flourish, however, our posture is important: we must be upright, firmly rooted in the earth with our head held high in the sky. Our adroitness is not tense, because there is a grace in this poise, like a dancer balanced, twirling on her toes. The best meditation (Zazen) comes from this posture, and some masters have taught that such a posture is completion, without remainder. In an upright posture, the mind naturally and without effort begins to settle into quietude; and as it quiets down our true nature - which was there all along - shines forth from out of the space we've just made. With a bit of inner emptiness, the world and Truth come rushing into our open hearts. The best tea is also prepared in such a posture, unaffected though upright. Within the Chinese character for "Tao" is the radical for the "upright man", because the ancients knew how important our spines were, likening the spiritual journey to a vertical dimension which is perpendicular to the horizontally mundane flow of time from past to future.

But Zen can never be forced. There is no ultimate subtlety you can sell in a book or carry around in your pocket. The secret of the universe isn't even knowable. You are living it. In being alive, the world is experiencing itself through you; and when you set aside the distinction between your mind and the world, and let outer quietude harmonize with inner stillness, the Buddha then meditates, not you.

Most of our day is devoted to doing, always focused on the outward - actively pursuing this or that. But then the rhythms of Nature strum in discord to our lives, and the sound is clashing and odious. This noise disrupts the peace of individuals and whole societies. Nature always balances times of stillness with activity - day and night, winter and summer, foraging and hibernation. For most people, however, the noise of our daily activities leaves us restless at night as well.

Through the last few centuries, we have developed amazing technology, harnessing the power of the human intellect: we've connected the globe through computers, breached the heavens with aviation and space travel, and even extended the normal life-span through medical advancements. Nevertheless, in order to focus exclusively on the rational part of ourselves, we have for the most part abandoned another, older intelligence: a feeling of being connected to the world, which you could call "instinct" or "intuition". Being a part of Nature came naturally to our ancestors, as it does to plants and animals. They didn't just study the stars or seasons, they felt a part of them - in harmony with the dance. The distinction between the mind and the world wasn't as gross, in other words. Lost in our minds, and an endless stream of dialogue about our doings, comings and goings - work, entertainment and personal drama - our connection to Nature has all but fallen to the wayside.

And yet, it would be further delusion to glorify the lives of our ancestors (and Zen is always about Reality). Such a life had its hardships. We cannot go back, and who would want to discard many of the useful and wonderful innovations we've created and discovered. Our future is forward. But we mustn't stop learning from the ancients, though we don't ape them. We must continue to be able to harness the intellect, while at the same time not being ruled by it. To govern the mind and its power as a secondary instrument of our beings - which are in accord with Nature and the Tao, and always were - is the divine life, as an individual and as a species.

One of the most resonant of our dissonant chords, in this modern life, is just this very hyperactivity. We need to remember, as does Nature, that there is a time for rest and a time for vigor, a time for growth and another for decay. To align ourselves with the coming together of energy works much better than trying to force Nature to behave in the way we want it to, just as it is important to appreciate the periods of dissolution and face them with openness, honesty and acceptance, rather than trying to hide death and disease, or regard them as unmentionables. The current carries us whether we want it to or not, and fighting it only makes the journey seem troubled and pointless. But there is a skill to navigating the river, using its currents - deft placement of an oar here or there to steer the boat. That is where Zen comes in: Zen is life's paddle, you could say.

The Buddha separated his 'Eightfold Path' into "skillful", "wholesome" or "balanced" means - depending on how you translate the Pali word "samma". Zen is all about coursing this life more skillfully and gracefully, not resounding lightning powers of Enlightenment (with a capital E). It is skillful to seek emptier, quieter spaces now and again. Of course, a much more powerful Zen is one in which we can stay connected to empty space while in the midst of activity, but even thus we must return to the well of outer space and quietude now and again to drink and replenish our soul. Zen is but the skillful means (upaya) to traverse this life.

As soon as the body is postured, the mind settles. The fact that this is a necessary part of human development - like air, food or water - should be obvious, since the movement inwards occurs naturally as soon as distractions are cut off and the body settled. Our ancestors achieved this by living and eating simply. After a hard day's work, they slept soundly and naturally. There is an old Chinese tale of a farmer who shooed the mechanical pump salesman away, arguing that he would corrupt his grandson's mind, which was still young and impressionable. "I know what he doesn't," exclaimed the old farmer, clarifying: "If I mechanize everything, I will have nothing to be; and finding myself useless, how will I sleep at night?"

Our hearts beat themselves, and trillions of processes all happen to us and within us every day. If we had to control even a fraction of the functions that are balanced perfectly by Nature within our bodies, we'd have time for nothing else in a day. The capacity for clarity and peace is already within you, as is the ability to perceive clearly. As soon as you leave the city behind, you realize the birdsong and river arpeggio were always playing. It was you who needed tuning.

As you allow stillness to permeate your life, you more and more recognize the movement towards softness, and you grow more and more sensitive. The breath naturally becomes softer and softer as the mind quiets - it does this, not you.

It is a natural movement of Nature, requiring no human intervention. You just observe - be an open space, awareness - ready for whatever arises, like the empty cup. Your mind may wander. Let it. There is nothing to do...just be and let whatever happens occur on its own.Tea can be a great aid in cultivating outer quietude and inner stillness - Zen and tea are, after all, one flavor. It's hard to talk with a mouth full of tea. Besides, the tea wants you to be quiet. It invites you inward. At first you notice only gross flavors, but over time your tea drinking more and more becomes a time of quiet rest, introspection and stillness. This happens naturally. Then, you begin noticing more and more flavors, as if the tea were rewarding you for your newfound peace. You begin to notice things beyond the flavor and aroma. There are sensations: the way the tea touches the mouth and throat, and returns on the breath. Over time, these also become softer and softer, clearer and clearer as you become more sensitive. This only happens when there is outer quietude, which leads to inner stillness; and it isn't long before you realize that your own state of mind is the most important ingredient in the tea - it's not which tea or teaware, but how it's prepared. Eventually, you begin to experience the movement of Qi, which is the living energy within our bodies. Whether you move your foot or not you know it's there, even with your eyes closed, because you can feel it from the inside. You are feeling the electricity traveling through nerves to your brain, atomic movement and energy, Qi, or whatever else you wish to call it. Fine tea catalyzes this energy, causing it to move, and if you are quiet - without and within - you will begin to feel it.

The Chinese call the modern tea ceremony "gongfu tea". This "gongfu", means with skill and disciplined mastery. It refers to the art of living through all things, completely in tune with the Tao of that thing - the way its tendency moves - the Way it "wants" to be completed, in other words. And there are many legends of simple people defeating master martial artists with tea: intent on battle, they were pacified and the tea brewer was therefore victorious.

You might think Lu Yu's sensitivity is just a fable, too fantastical to be true, but as you begin to allow yourself to spend as much time being as doing - and let life turn inward - you'll realize it isn't that far-fetched at all. The connection is already there. Your mind is not separate from this world, but arose out of it. Every particle of every atom in your body was once in a star.

Become mind's master, not mind-mastered.

The feeling of connection is inborn, founded upon a real, undivided, non-dual world. Similarly, there is no distinction between life and tea. You might think that someone so caught up in holding tea sessions might like a day or two vacation away from it now and then, only to find that the Chajin takes his teaware to the mountain with him. Committed, each day then is itself the Way of Tea.

Tea in every way epitomizes the traditional Chinese attitudes toward Nature, the seasons and changes. There is a time for rest and sensitivity to it, ignored at the peril of your health. Though Lu Yu discusses tea's virtues in terms of such health, praising it for the alertness it offers, etc., it was this subtlety, sensitivity and stillness that were at the heart of his devotion to tea. Lao Tzu also said that the Tao was a returning to softness.

Through skill, loving attention to detail and spirit, tea opens us up - like so many twirling dervish-leaves - open to Nature's melodies as they play around, through and within us so that we once again live in concordance, indistinct from the world and its Way.

The doorway to Zen is always unlocked. The gateway is the body and mind you now experience, not some other. Find the time to just have some tea. All these words are good if they help direct you to that place. Otherwise, as Lu Yu suggested in the story, the words just ruin the tea - more than any bad water ever could.

葉浸水