|

|

APPENDIX: MASTER LU'S INSTRUCTIONS FOR DISPLAYING THE TEA SUTRA

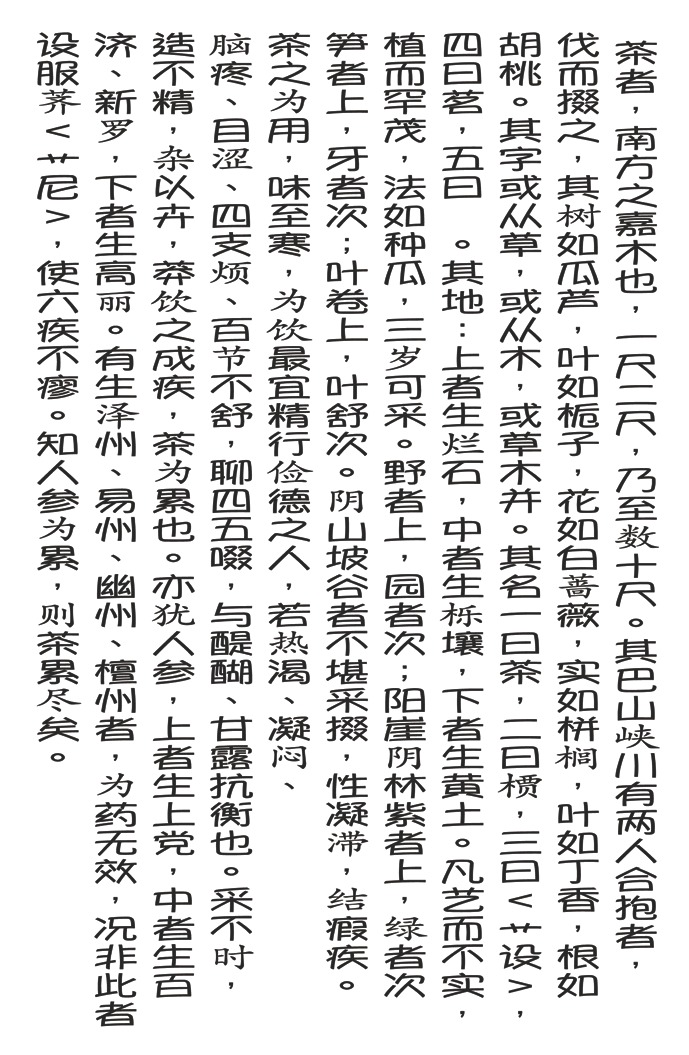

Tea is a magnificent tree growing in the South. Tea trees range from one or two feet to tens of feet tall. In Bashan (巴山) 1 and the river gorges of Sichuan there are tea trees growing to such a size that it would take two people hand in hand to embrace their circumference. Because these trees are so very tall, the branches need to be cut down to harvest the leaves. 2

The shape of tea trees resembles those of other camellia. The leaves look like those of a gardenia and the little white flowers are so many lovely rosettes. Tea seeds are like those of palms with stems like clover, while the root system is similar to walnut trees.

There are three different ways to interpret the character tea, "cha (茶)" in Chinese. It could be categorized under either the "herb (艹)" radical, the "tree (木)" radical, or both "herb" and "tree" radicals.3 There are four other characters that have also denoted tea through history other than "cha (茶)". They are "jia (檟)4", "she (蔎)5", "ming (茗)6" and "chuan (荈)7."

Tea grows best in eroded, rocky ground, while loose and gravely soil is the second best and yellow earth is the least ideal, bearing little yield.

If one is not familiar with the horticultural skills needed to tend tea trees and the trees are not thriving, then one should cultivate them like melons.8 Three years later, the leaves can be harvested. Wild tea leaves are superior to those cultivated in plantations.9 For the tea trees grown on a sunlit wooded slope, the newly budded burgundy leaves are better than the green ones. Curly leaves are considered higher in quality than open and flat ones. The leaves harvested from trees that grow on the shady slopes or valleys of a mountainside are not suitable for drinking, because they may cause internal stagnation or indigestion.

According to Chinese medicine, the property of tea is very cold. It is a great drink for those practitioners of the Tao in their spiritual cultivation. It alleviates discomfort when one feels thirsty and hot, congestion in the chest, headaches, dry eyes, weakness in the limbs and aching joints. It also relieves constipation and other digestive issues.10 As little as four to five sips of tea works as fine as ambrosia, the elixir of life. Its liquor is like the sweetest dew of Heaven. However, drinking tea made with leaves that were picked at the improper time, out of harmony with Nature, leaves that were not processed well, or tea adulterated with other plants or herbs can eventually lead to illness.11

Similar to ginseng, the potency of tea grown in different regions is different. The best ginseng is grown in Shangdang,12 the second grade is grown in Baekje and Silla,13 while the lowest grade is grown in Goguryeo.14 Ginseng grown in the Zezhou,15 Yizhou,16 Youzhou17 and Tanzhou18 areas of China has no medicinal potency at all, not to mention other ginseng. If one unfortunately takes ladybell,19 which bears a strong resemblance to ginseng, it could even cause an incurable disease! Understanding how different kinds of ginseng have different effects, you can appreciate how diverse the affects of different kinds of tea are.20

The tools for processing tea are:

There are many names for the baskets used in tea picking. Ying (籝), lan (籃), long (籠) and lu (筥) refer to the baskets made of loosely woven bamboo strips with capacities from one to five dou (斗).1 Tea pickers carry these bamboo baskets on their back. They have relatively large gaps in the weaving to keep the leaves well ventilated while picking.

A stove, called a "zao (竈)", burns logs without a smokestack or chimney.2 A big thick iron or clay wok called a "fu (釜)" is used in the steaming of tea. Always use one with a wide rim.

The wooden or clay steamer is called a "zeng (甑)". It does not taper down like most other ancient Chinese steamers used for cooking. It has a drawer or door for easy access to the handle-less bamboo basket, which is tied to the steamer using bamboo strips. After putting some water in the wok, the bamboo basket full of tea leaves is put into the zeng to begin steaming the leaves. When this step is done, the basket is taken out of the zeng. If the water in the wok evaporates, added water can be poured directly through the steamer. A threepronged branch is used to spread out the steamed leaves so that the tea juices do not evaporate.

The mortar and pestle (chujiu, 杵臼) are also called "dui (碓)" as a pair. It is best to designate a pair that grinds steamed tea leaves exclusively. Since the pestles are made out of wood and the mortars are made out of stone, and tea leaves are prone to absorb flavors and odors, it is best that this pair only come in contact with tea leaves and nothing else.

A mold (gui, 規), also know as "mo (模)" or "quan (棬)", is used to press the steamed tea leaves into cakes. Molds are made out of iron, and can be shaped as squares, circles or other decorative patterns.

There is a table (cheng, 承), also called "tai (台)" or "zhan (砧)" on which the steamed tea leaves are pressed into molds to make tea cakes. The tables are usually made out of stone for strength and stability against the force of pressing. However, they can also be made out of pagoda or mulberry trees. In that case, the legs of the table should be half-buried into the ground for anchor.

A piece of oily silk or a ragged, worn-out raincoat called "yan (檐)", or other cloth (yi, 衣) is placed on top of the table. The molds are put on top of this piece of cloth so that after the tea cakes are made, they are easily collected. After the tea has hardened, the cakes can be easily moved by lifting up the table cover.

There is also a sieve called a "bili (芘莉)" or "yingzi (羸子)". Bamboo strips are woven around two threefoot-long bamboo poles, leaving handles of three inches on both ends of the poles, to form a large sieve. It has square holes and is similar to those that farmers use to sieve earth in the field. Tea leaves are poured onto these sieves so that each leaf will be thoroughly separated from the others.

A small awl with a hardwood handle, called a "qi (棨)" or "zhuidao (錐刀)" is employed to punch a hole through each tea cake so that they can be strung together.

A two-and-a-half-foot long bamboo skewer called a "guan (貫)" is used to string up tea cakes ready to be baked dry.

Bamboo twine called "pu (撲)" or "bian (鞭)" goes through the holes of the tea cakes to string them together for easier transportation.

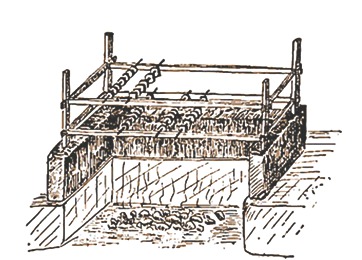

A two-tiered, one-foot high wooden rack called a "peng (棚)" or "zhan (棧)" is placed on the top of the walls above the fire pit. The skewers with tea cakes are then placed on these racks. The half-dried cakes will be placed on the lower shelf while the nearly-finished cakes will be moved to the top shelf.

A fire pit called a "pei (焙)" is dug to dry the tea. It is two feet deep, two and a half feet wide and ten feet long with two-foot high clay walls above ground.

The measurement used for bulk cakes is called a "chuan (穿)". The people southeast of the Yangtze River and south of the Huai River string cakes together with bamboo strips, whereas upstream of the Yangtze River and in the Yunnan area, cakes are strung together with mulberry tree bark. In the lower Yangtze and Huai River areas, one shangchuan (上穿) is about one pound or 500g, a zhongchuan (中穿) is about half a pound or 250g and a xiaochuan (小穿) is about 1/3 of a pound or 120-150g. While in the upper Yangtze River or Yunnan (雲南) areas, a shangchuan is about 120 pounds or 60kg, a zhongchuan is about 80 pounds or 40kg and a xiaochuan is about 50 pounds or 25kg. In the old days, there were two alternative characters employed, "chuan (釧)" and "chuan (串)". These two characters both bear the same pronunciation as the current character, and yet are pronounced in the fourth tone.3 Like the following five characters, mo (磨), shan (扇), tan (彈), zhan (鉆) and feng (縫) they are written in characters with the first tone and yet are spoken in the fourth tone as verbs. By the same token, it is recorded as "穿" here.

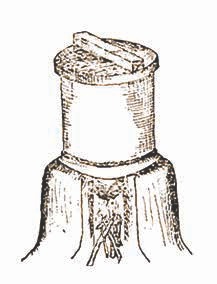

A covered wooden storage container, called a "yu (育)", is used to preserve tea cakes. It has bamboo walls covered in a paper finish. There are partitions and racks in every chamber. Below, there is a door. Behind the door there is a fan4 and a stove with constant low heat.5 This maintains the freshness of the cakes. However, for people living in the South, during the rainy season, a fire will be needed to keep the tea dry.

In general, tea leaves are picked from the second to the fourth lunar months, when the young shoots have grown to between four and five inches on the most verdant trees, growing in rocky, fertile soil. Similar to edible wild ferns and herbs, the best time to pick is early in the morning before the dew has evaporated. When the shoots are thick and flourishing, pluck the tea down three to five leaves in, only picking the best and brightest leaves. The weather is crucial for harvest. There is no picking on a rainy or cloudy day. The tea leaves gathered on a clear day will be steamed, crushed, pressed into cakes, roasted dry, skewered, and sealed before the end of the day.

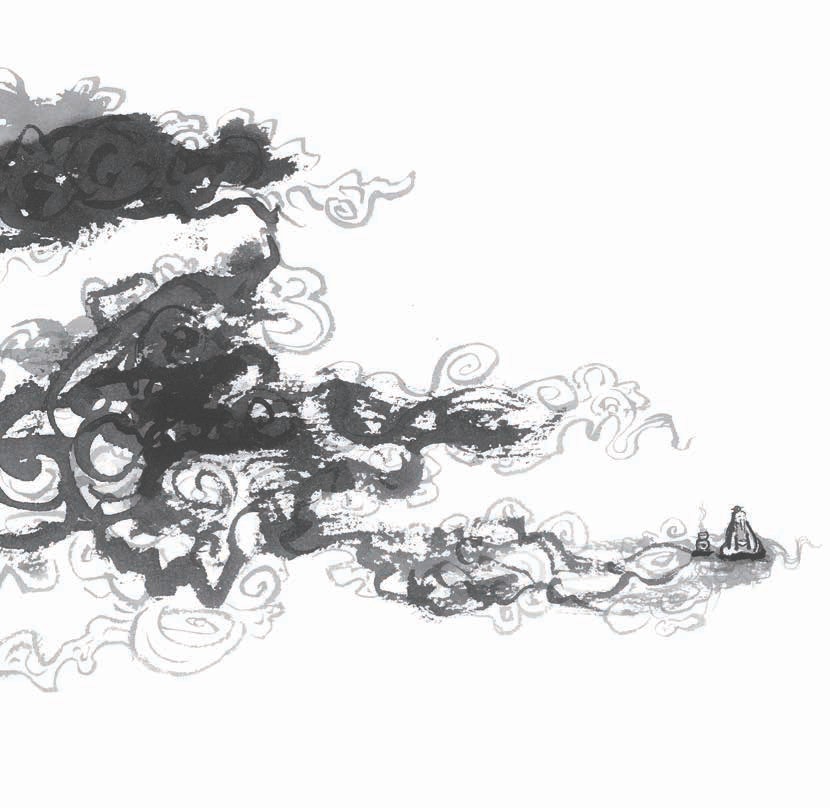

There are myriad shapes of tea leaves: Some look like the wrinkles of a barbarian's leather boots, while others are like the bigger folds of a cow's neck. Some turn upwards like the eaves of a house or barn. Tea can look like breezy clouds streaming out from behind a mountain peak, or have wavy patterns like the surface of a windswept lake. In terms of the consistency of the cakes, some look like clay, soft and malleable, ready to be made into ceramic utensils; while others have the consistency of a field right after ploughing, or the earth after a thunderstorm. These are all signs of fine, young and tender tea. On the other hand, when the tea leaves have grown too large, the tough fibers are not easily compressed, even after steaming. As a result, rough strands like those of old bamboo husks can be seen in the cakes. On other occasions, if withered or frostbitten leaves are used, then the damaged and dying fibers are also visible in the cakes. These two situations are indications of lower-quality tea.

The whole process of tea production can be divided into seven steps, from picking the leaves to sealing them.1 There are eight grades of tea, from the small, wrinkled leather boots to the dewy lotus petals of a windswept lake. Those people who think the shiny black and smooth-looking teas are the top ones have no ability to distinguish fine tea. Those who think that good tea should look yellowish with uneven wrinkles or folds have better taste in tea. However, those who can describe in detail all the elements of fine tea are the true connoisseurs.

For every quality, good or bad, there is a reason. If the moisture in the leaves is lower, then the tea cakes will look shiny. However, when the leaves are tender and juicy, the surfaces of the pressed cakes roll in wavy crests.2 If the tea leaves have been left overnight before processing, then the cakes will look dark when they are finished. On the other hand, cakes that are made the same day the leaves were harvested will be yellowish-green. If the cakes have been processed at night, they will be darker, but if they are made during the day, they will be brighter and more yellow. If the crushed leaves were pressed firmly into the mold, then the cakes will look finer. If the crushed leaves were compressed into the mold with less pressure, then there will be uneven patterns on the cakes. Ultimately, the liquor will not lie. In other words, tasting is believing.3

The Utensils for preparing tea are:

The brazier or furnace (fenglu, 風爐) is a bronze or iron three-legged stove, shaped like the ancient offering cauldrons at temples (ding, 鼎 ).1 It should be a quarterinch thick near the rim, and thinner in the body. The hollow space is filled with ashes to maintain a steady heat.2

The inscriptions on the three legs of my brazier are as follows: One leg has the three trigrams: "kan (坎), xun (巽) and li (離)" from top to bottom;3 the second leg says "a body harmonized in the five elements will elude the hundred diseases"; and the third says "made in the year after the holy Tang Dynasty drove the barbarians out of China".4 Between the legs, there are small openings with two characters inscribed above each one. These are draught windows to increase airflow. These six characters read "Minister Yi's stew and Lu's tea (Yigong geng Lushi cha 伊公羹陸氏茶)."5

Inside of the furnace lies a stand (dienie, 墆嵲)" with three protruding prongs on which the cauldron is placed. The three sections between any given two prongs are decorated with one trigram and one animal each. They are a zhai (翟), the phoenix with the li trigram symbolizing fire, a biao (彪), the winged chimaera with the xun trigram symbolizing the wind and a fish with the kan (坎) trigram symbolizing water. The wind stirs the fire, which boils the water. Therefore, these three trigrams are engraved on my brazier.

On the body of the brazier, there are decorative patterns such as the double lotus, dangling vines, meandering brooks, and linked rhombi in ornate geometric patterns. On the bottom of the furnace, there is yet another opening for cleaning out the inside. Beneath it, there is an iron tray (huicheng, 灰承) with three little legs to collect ashes from the bottom opening.

While most braziers are wrought of iron, they can also be made of clay.6

A hexagonal coal container with a lid called a "ju (筥)" is fourteen inches high and seven inches in diameter. It is either made of bamboo or rattan. Some people make a hexagonal wooden inner mold first before making this basket.7

Another hexagonal utensil is the coal breaker and fire stoker, "tanzhua (炭撾)". It is one foot long with a pointed end, tapered at the other end so that it is easy to grip. The tapered end is decorated with some metal chains. It is similar to the weapon used by the soldiers in Shanxi Province (陝西 ).8 One can also use a hammer or axe to break up the coal at one's convenience.

The tongs (huojia, 火筴) for picking up coal are also called "chopsticks" because they are a pair of iron or copper sticks. They are one and a quarter feet long without any decoration at the ends.9

A fu (鍑) is a cast iron kettle with square handles, which is an aesthetically pleasing blend of round and square.10 The best cauldrons are made of pig iron (鑄鐵),11 though blacksmiths nowadays often use blended iron, too. They often make kettles out of broken farm tools. The inside is molded with earth and the outside with sand. As a result, the inside is smooth and easier to clean while the outside is rough and heats up faster. It has a wide lip so it is more durable. Since it is wider than it is tall, heat is more concentrated in the center. As a result, the tea powder can circulate in the boiling water more freely and the tea is much better. In Hungzhou12 people use ceramic cauldrons, while in Laizhou13 they are made of stone. Ceramic and stone are both nice materials, but they will not last as long. Silver is extravagant, but when it comes to beauty and purity of water nothing compares. For the best tea and longest lasting kettle, one always resorts to silver.

After the water is boiled, the cauldron is then placed on a small folding stand, which is called a "jiaochuang ( 交床)". It has a round hole in the center for the kettle.

Green bamboo tongs are used to roast tea cakes over the fire. They are called "jia (夾)". The jia are made from a fourteen-inch-long bamboo stalk. Choose the bamboo carefully; only pieces with a segment joint one inch from the bigger end should be used. The bamboo is split all the way from the slimmer end to the joint. The fragrance of bamboo will seep out while roasting tea over the fire, gently flavoring the tea. However, such tongs are not easy to acquire if one does not live near a forest with bamboo groves. As an alternative, wrought iron or copper sticks are employed for their durability.

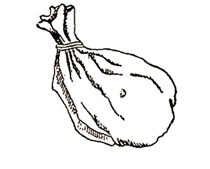

The roasted tea cakes are put into a special envelope called a "zhinang (纸囊)" to preserve their fragrance. This envelope is made of double-layered, thick white paper made of rattan from the Shanxi (剡溪) area.14

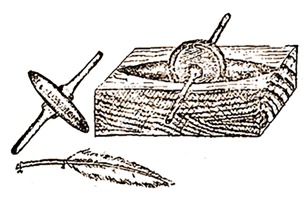

A grinder called a "nian (碾)" is used to grind the roasted tea into powder. The best material for the bottom part of the grinder is mandarin orange timber, or pear, mulberry, paulownia, or Tricuspid cudrania timber. The bottom part is a rectangle on the outside for the sake of stability, and the inside is a concave oval shape to ease the gliding motion of grinding. Inside the center sits a wooden roller with a diameter of three and threefourths inches. The roller is one inch thick at the center where there is a square hole, and only half an inch thick at the rim. The spindle that goes through the hole of the roller is nine inches long and one and seven-tenths inches thick. The ends of the spindle tend to become rounder after a long period of usage, while the central part remains square. The residual tea powder is collected with a feather brush called a "fumo (拂末)".

The freshly ground tea powder is then put into a lidded container with a sieve called a "luohe (羅合)". The sieve is a piece of silk or muslin stretched over the bottom of one compartment of the container. The sieved tea power will be stored in the one-inch-high compartment, while the measuring spoon, ze (則),15 will be stored in the main container, which is four inches in diameter and two inches high. This caddy is usually made out of bamboo, with the segments as the natural bottom and top. It can also be made of painted or lacquered cedar.16

The measuring spoon, "ze (則)", can be made of shell, bronze, iron, or bamboo. The character "ze" itself means "to measure" or "the standard". In general, for 200ml of water, a medicine spoon17 of tea powder is about right. However, for those who enjoy weaker or stronger tea, the amount can be adjusted accordingly.

The cubic water container has a volume of two liters. It is called a "shuifang (水方)". It can be made out of many different kinds of wood such as pagoda or catalpa trees. It is then lacquered so that it won't leak.

Water drawn from Nature has to be purified with this filter (lushuinang, 漉水囊). If the filter is used often, then the rim had better be made of untreated copper, because a patina tends to happen to wrought copper or iron, and that tends to make the water taste strange. Hermits in the woods often use wood or bamboo filters. However, wood and bamboo are not durable. As a result, copper is the best choice for making the rim of one's filter. As for the filter itself, it is made of woven bamboo strips and covered with jade-green colored double-threaded silk. Decorative stones and crystals are sewn to both ends of a string on which one can hang the pouch to dry.18 In addition, a green oilcloth bag is designed to store the filter. The size of the pouch is five inches in diameter with a one-and-a-half-inch long handle.

A foot-long, thin stick made out of bamboo, walnut, willow, Chinese palmetto, or the center of a persimmon tree is termed the "bamboo stick (zhuce, 竹筴)".22 It is used to stir the tea while it is being boiled in the cauldron (fu). Therefore, both ends of the stick are protected with silver plating to prevent flavor contamination.

This round, ceramic container is called a "cuogui (醝簋)". Its diameter is four inches. It can be shaped like a box, bottle, jar or vase, with or without a lid. It contains the salt, which will bring out a more favorable taste in the tea. The thin spoon used exclusively for salt is made of bamboo. It is four and one-tenth inches long and nine-tenths of an inch wide.

The container for boiled water is called a "shouyu (熟盂)". It is made out of clay and has a volume of about half a liter.23

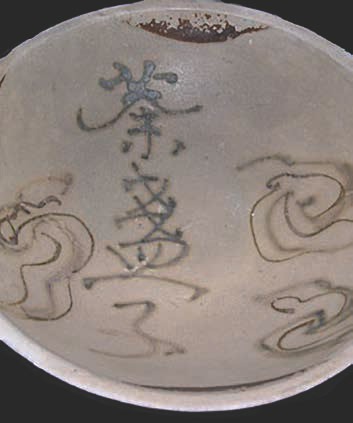

There are many different kinds of tea bowls (wan, 碗), each with a different provenance and style of manufacture, representing the many different kilns.24 In the order of superiority, they are Yuezhou,25 Dingzhou,26 Wuzhou,27 Yuezhou,28 Shouzhou29 and Hungzhou.30 Some think that Xingzhou31 wares are better than Yuezhou (越州) wares, but I do not agree. First of all, if Xing ware is like silver, then Yue ware is like jade. If Xing ware is like the snow, then Yue ware is ice. The white Xing bowls give the tea a cinnabar hue, while the celadon Yue bowls bring out the natural green of the tea. Odes of Old Tea Leaves, written by Du Yu, says that "If you are looking for ceramics, the best are from Eastern Ou."32 Ou is an alternate name for Yue. Ou wares tend to look similar to the Yue (越) wares except the rims do not curve out and the bottoms tend to be shallower and curve inward. Also, the capacity is less, usually 100ml. Both Yue (越 and 岳)33 wares are celadon, which is good for tea because it will bring out the true color of a tea, whitish-red for a light red tea, for example. Such a red tea would look rusty in a white Xing ware, and the yellowish Shou wares cast a purple hue on the tea.34 The brownish Hung wares make tea look black. These last three bowls are not as good for tea.

A ben (畚) made out of woven white palmetto leaves can hold up to ten bowls. Some also use a bamboo container covered with paper to carry their bowls. Oftentimes, these are square and it takes ten layers of paper to finish them.

A brush made from a bundle of palm bark with dogwood branches on the inside is called a "zha (紮)". Alternatively, bamboo stalks tied together also work. It looks like a huge Chinese calligraphy brush.35

A small square water container called a "difang (滌方)" is made out of qiu (楸) wood.36 It holds up to one and a half liters of waste water. An even smaller, square waste bin is called a "zifang (滓方)". It holds up to one liter.

Two small towels made out of tough and thickly woven silk called "jin (巾)" are used to clean and wash the utensils on the table.37 The length of the towels is about twenty-four inches.

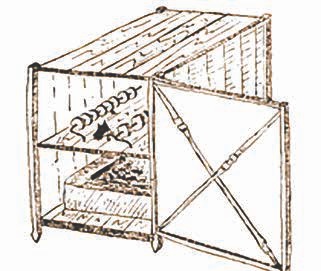

All the smaller utensils can be placed on a rack called the "julie (具列)". It can be made of wood, bamboo, or a combination of both. The name "julie" literally means, "display them all" in Chinese, though some people simply call it a "bed" or a "rack". It is usually dark brown in color, three feet long, two feet deep and six inches high.

A rectangular bamboo basket called a "dulan (都藍)" functions as storage for all the bigger utensils. Inside the basket, bamboo strips are woven to form square cubbyholes. Over the outside, slightly wider bamboo strips are doubled over a thinner bamboo strip, weaving in and out to create beautiful square patterns. The teaware basket should be one and a half feet tall, one foot across the bottom and around two inches thick. It should be two and a half feet long, opening to two feet at the top.

Do not roast tea cakes when the fire has almost gone out, because a dying flame is not steady and the tea leaves are then not roasted evenly. You should hold the tea cakes very close to the flame and turn them often. Once the cakes are roasted, bumps like those on a toad appear. Then, the cakes should be held about five inches from the flame to continue roasting. Wait until the curled-up leaves start to flatten, then roast the tea one final time. If the tea was dried by fire in the first place, then the cakes should be roasted until they steam. If the leaves were dried in the sun, then roast the cakes until they are soft.

The leaves should be crushed right after being roasted until they steam or are soft. If the leaves are tender, then they are easily crushed, though the stems may be tough. Without proper roasting, even the brutal force of a half-ton hammer couldn't crush the stems. They are not unlike the tiny and slippery beads of lacquer trees that cannot be broken by even the strongest man. However, after roasting properly, they are as soft as a baby's arms and easily crushed. While the crushed leaves are still warm, they should be stored in the paper tea envelopes to seal in the aroma. Only after they have cooled down should they be ground into powder.

Fire for tea should be fueled by charcoal, but without that hardwood is the second best option. Coals which have been used to roast meat or cook food will infuse the odors of cooking into the tea. Therefore, always use clean and pure coals to roast tea cakes or boil water. Those trees that secrete oily resin or decayed timber should not be used as fuel either. Ancient people often commented that some food could "smell of withered timber", and I could not agree more!1

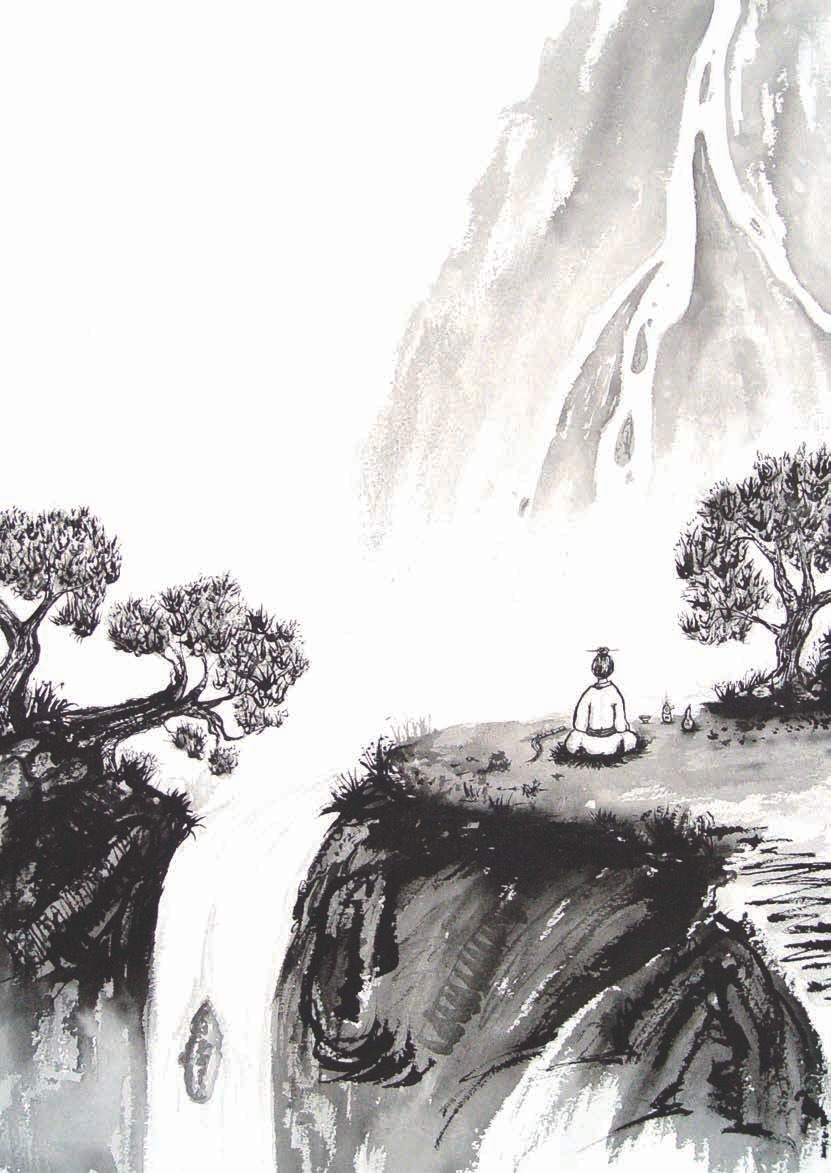

As for the water, spring water is the best, river water is second, and well water is the worst. The best spring water flows slowly over stone pools on a pristine mountain. Never take water that falls in cascades, gushes or rushes in torrents or eddies. In such mountains where several rivers meet staggering together, the water is not fresh and may even be toxic, especially between the hottest part of summer and the first frost of autumn when the dragon is sequestered.2 It takes but a single sip of water to understand its nature. However, even stagnant water can be used after an opening is made to let the water flow freely for some time. For river water, the more remote the source, the better the water will be. On the other hand, well water is better when more people use it, as this helps circulate its energy.

When the boiling water first makes a faint noise and the bubbles are the size of fish eyes, it has reached the first boil (yifei, 一沸). When strings of pearls arise at the edge of the kettle, it has come to the second stage (erfei, 二沸). When the bubbles are much bigger and waves of water resound like drumming, then the water has reached the third boil (sanfei, 三沸). Beyond this stage, the water is over-boiled and too old to be use for brewing tea.

When the boiling water has reached the first stage, one should add salt according to the volume of water. You can taste the water to be sure the amount is correct, but be sure to discard the remaining water from the ladle after tasting. Don't put too much salt, especially since you may not taste the salt right after it has been added. Otherwise, the salt will overpower the tea. During the second boil, one should scoop out a ladle of boiling water for later use. The ladled bowl of water is kept in the hot water basin that is used exclusively for this purpose. Then, using the zhuce, the long bamboo stirring stick, one revolves the water in the center of the pot so that the boiling water begins to swirl like a whirlpool. Next, use the measuring spoon to add tea powder in the appropriate amount to the eye of the vortex. Shortly after the tea turns and churns, mixing in, the water will come to the third boil, roaring like tumbling waves. This is the time to return the hot water you took out at the second boil to the cauldron. This prevents the tea from over-boiling, splattering out and more importantly alchemizes the essence of the tea, the hua (華).3

At this time, the tea is ready to serve. One should let the froth settle and spread evenly in the bowls. A thin froth is called "mo (沫)", while a thicker froth is named "bo (餑)". The former is like a bright green algae floating near the river's edge or chrysanthemum blossoms falling into a bronze vessel used to brew medicine. The thicker kind of froth is created by over-boiling the tea. The longer it boils, the heavier the essence becomes, and the froth accumulates. This is not unlike the layers of snow that grow on the ground over the course of a winter. The light and frail froth is termed "hua (花)",4 not unlike date flowers drifting across the surface of a pond, or young duckweed just budding in nascent waters, or even a wispy cloud brushed across a clear blue sky. In his Odes of Old Tea Leaves, Du Yu also describes tea froth as "... shiny as freshly fallen snow and as bright as the sprouting grass of a spring dawn."

If there is a film of black on top of the water, then scoop it out.5 Otherwise, it will destroy the taste of the tea. This first boil of tea tastes the best, and the aroma lasts for a very long time.6 One can save some of the first boil of tea for later, to pacify crashing, splashing water and to cultivate the essence of later boils.7 The first three bowls are indeed the best. Unless one is extremely thirsty, the rest of the tea is not worth drinking. In general, 200ml of water can make five bowls. One should drink them consecutively while they are still hot. The heavier elements and tea dregs will sink to the bottom of the bowl while the essence will float to the top. Therefore, the tea should be drunk hot before the essence vaporizes.

It is not a good idea to drink too much.8 Moderation is the virtue of tea. The liquor itself should also be frugal, meaning it doesn't have too strong a flavor. Therefore, learning the proper amount of tea to add is essential. If you brew with too much water, the tea becomes too thin. When you drink half a bowl and find out it does not have much of a flavor, imagine what it would have been like had you used even more water with the same amount of tea powder! The color of the tea should be light yellow and very aromatic, with a bright fragrance surrounding the tea space. If the tea tastes sweet, then it is the brew of what we call "guan, (樌)" leaves9; if it is not sweet but bitter, then it is a brew of old tea leaves.10 But if it tastes bitter at first but after you swallow it has a sweet aftertaste, then it is truly tea!11

All creatures big and small, including the winged ones that fly, those with fur that run, and those who have mouths to speak - all need to drink water in order to survive. That is the basic essence of drinking, but at times the meaning of what humans refer to as "drinking" is more ambiguous. To quench the thirst one can drink water; to escape worries or anger, people turn to wine; but to dispel sloth and torpor,1 there is but one meaning of "drinking", and that is tea!

Now tea as a drink was first discovered by the legendary God of Farming, Shennong,2 as recorded by Duke Zhou of Lu (鲁周公). Throughout history, there have been many famous tea drinkers, such as Yan Ying of Qi (齊),3 Yang Xiong,4 Sima Xiangru of Han,5 Wei Yao of Wu (吳),6 Liu Qun,7 Zhang Zaiyuan (張載遠), Lu Na (陸纳),8 Xie An9 and Zuo Si of Jin (晉)10. After these great men, tea drinking has become more and more popular. Nowadays, in the Tang Dynasty, if one travels to the two biggest cities, Xian (西安) and Luoyang (洛陽), or to the Hubei (湖北) and Chongqing (重慶) areas, one finds that tea is a household drink.

There are four different kinds of tea: rough tea, loose tea, tea powder, and tea cakes.11 If one wants to casually brew a fresh tea cake, one needs to pry open the cake with a knife, roast it until it steams and the juice vaporizes, chopping it into fine pieces. Afterward, put it into a vase, add hot water and gently shake it. This is known as "half-cooked tea (夾生茶)". Some people boil tea with green onions, ginger, dates, orange peels, dogwood, and/or mint. Then, they either keep scooping and pouring the tea back into the pot to mix it as it boils, so it tastes smoother and does not foam, or they simply scrape off the dregs and foam. This kind of tea is not unlike the swill of drains and ditches, and yet, alas, many people are accustomed to drinking it!12

All things on Earth are born with unique and mysterious wonders, and yet only a human can master and perfect a life. No mere shelter, we live in intricately designed houses, dress in fabulous clothing, eat delicious food and drink exquisite alcohol. Such refinement, and yet most people do not know how to prepare and drink fine tea!

There are nine skills one must master in a life of tea:

Processing the leaves

Discrimination of quality

Understanding the utensils and their use

Preparing the proper fire

Understanding and selecting suitable water

Proper roasting of the tea

Grinding the tea into powder

Brewing the perfect elixir

Drinking the tea

To pick leaves on cloudy days and roast them at night is not the sign of skillful tea processing. To but nibble the tea leaves and sniff their fragrance is not truly discerning quality.13 Pots used for cooking or bowls that smell of food are not appropriate implements for brewing tea. Similarly, firewood contaminated with oil or mere kitchen coals are not suitable for brewing tea, either. Rapidly moving or stagnant water sources are not worthy of a fine tea. When roasting tea cakes, if the outside is done while the inside is still raw, one has more practice to do. Do not grind the tea leaves into too fine a powder. Neither stirring boiling water with jerky motions nor too vigorously is proper brewing. One must stir gracefully and smoothly.14 And lastly, drinking tea only in one season, like during the summer yet not much in winter, is not conducive to a true understanding of tea.15

For the most exquisite tea, the essence should manifest in but three bowls.16 When one pot makes five bowls, the tea does not taste as good. But if you can be satisfied with a compromise in quality, five bowls are permissible. If you have five guests, it is better to serve three bowls of tea for them to share. If you have seven guests, then make five bowls and pass them among the guests. If you have six guests, then make five bowls and use the hot water basin as the sixth.17 If a guest is missing from your gathering, then the spirit of the tea must take their place.18

The historical notes on tea are:

It is written in Shennong's Treatise on Food "If one drinks tea regularly, one will be more physically active, be contented of mind with a strong determination and focus in work."

The Duke of Zhou (周公) wrote in Erya (爾雅) that "jia" is a kind of bitter tea.1 And in Guangya (廣雅), it is recounted that "In the Hunan and Sichuan areas, people pick tea leaves to make tea cakes. If the leaves are old and stale, soak them in rice water. Before brewing, roast the cakes to a red color first, then grind them and put them in ceramic wares, pouring hot water over them.2 Or cook the ground tea leaves with green onion, ginger, and orange peel. Such a drink is good for a hangover, and will prevent drowsiness."

In the Biography of Yanzi (晏子春秋), you can find the following: "When Yanzi was the prime minister under Duke Jing of Qi (齊景公), he only ate millet, some poultry, eggs and drank tea."3

Sima Xiangru listed tea among other medicinal plants and animals in one essay on linguistics.

Yang Xiong said, "In southwestern Sichuan, people refer to tea as jia (葭)" in his linguistic anthology, Fangyan (方言).

The Biography of Wei Yao in the History of Wu (吳志·韋曜傳) states that "Whenever Emperor Sun Hao (孫皓) had a banquet, all the officials had to drink at least one and a half liters of liquor. Even if one could not finish that much, one had to take the quota and deal with it. However, Wei Yao could not drink more than half a liter of liquor. When Sun Hao first ascended to the throne, he respected Wei Yao so much that he secretly gave Wei Yao tea instead of liquor."

One account in Jin Zhongxing Shu (晉中興書) says that "When Lu Na (陸納) was the state governor of Wuxing (吴兴), the household learned that the dignitary Xie An wanted to visit Lu Na. Lu's nephew Shu (俶) heard about it, but would not dare to ask his uncle why he was not preparing for Xie An's visit. Shu prepared food for more than ten people by himself. When Xie An came, as expected, Lu Na only had tea and fruits for Xie An. Shu took out the exquisite feast he had made. After Xie An left, Lu Na gave his nephew forty spanks and scolded him, saying, 'What you did not only failed to honor your uncle, but also made me look uncouth!'"4

The History of Jin (晉書) asserts that "When Huan Wen (桓温)5 was the governor of Yangzhou6 he lived humbly. Whenever he had a banquet, there were only seven dishes of fruit, pastries, cakes and tea, and nothing else."

There is an interesting account about tea in the fantastic fourth-century collection, In Search of the Supernatural (搜神記).7 The story goes that Xiahou Kai (夏侯愷) contracted a disease and passed away. After his death, someone in his household who could see spirits saw his ghost in the stable looking for his horse. "The spirit was dressed in the attire he had worn when he was alive: a flat-topped hat and a single-layered shirt. He sat on a big chair against the west wall and when people passed, he asked them for tea. At night, the ghost went into his old bedroom and his wife got sick the following morning."

Liu Kun (劉琨)8 once wrote to his nephew who was the state governor of Nanyanzhou9 about a prescription: "I acquired a pound of dried ginger, cinnamon and huangqin (黄芩),10 each of which were exactly what I needed. I've also often felt I have edema, and rely on drinking tea to feel better. You can do the same."

Fu Xian (傅咸)11 wrote in his Records of the State Capital (司隸教)12 that "I once heard that in the south market there was a poor old lady from Sichuan (四川) selling tea cooked with green onions, ginger, and orange peels in order to make a living. Some local clerk broke her utensils and even forbade her to sell tea in the market. I wonder why the clerk wanted to make the old Sichuan lady's life difficult?"

Another collection of fantastic stories, Notes on Divine Marvels (神異記), also records a story about tea. "Yu Hong (虞洪) from Yu Yao13 went wandering into the mountains to pick tea. He encountered a Daoist grazing his three cows. The Daoist led Yu Hung to Cascade Mountain, where the falls twirled straight down like a ribbon, and said, 'My name is Vermillion Hill. I've heard that you are a great tea lover and so have been hoping to meet you. I've wanted to share with you that deep up in those mountains there are huge tea trees. I hope that you find them. My only wish is that if you do, you will occasionally make prayers to them, offer them tea, and that you share some of your leftover tea with others.' So Yu Hong set up an altar as the Daoist suggested and prayed, asking the trees' whereabouts. Later, he often sent his family into the mountains to search, and eventually they found the big tea trees. From then on, there was enough for all the householders of his village to share in the harvest."

Zuo Si wrote in a poem about his lovely daughters that they were "so impatient for tea, they would huff and puff at the furnace when the tea was boiling."

Zhang Mengyang (張孟陽) brushed his poem on Chengdu (成都), reminiscing grand banquets held by celebrities such as Yang Xiong, Sima Xiangru, and Zhuo Wangsun (卓王孫).14 At the extravagant banquets, among all the enticing dishes and drinks, tea was by far the best to all: "Fragrant and beautiful, tea crowns the Six Purities.15 Its overflowing flavor spreads throughout the Nine Regions."16

In a poem listing all the best produce in China, amongst persimmons from Shandong and chestnuts from Hebei, Fu Xun17 considered tea from Sichuan the best.

Hong Junju (弘君舉)18 wrote in his passage On Food (食檄) that "After one has greeted one's guests, one first offers three bowls of fine tea with white froth, then offers sugar cane, papaya, plums, Chinese bayberry, olives pickled with five-flavored seasoning, and a starchy okra soup."

Sun Chu (孫楚)19 also wrote a poem on food, "The best part of the dogwood is the new leaves. The best carps are from Luo River. The best white salt is from the East coast, while the best ginger, cinnamon, and tea are from Sichuan..."20

The most famous physician in Chinese history, Hua Tuo (華陀),21 commented that "Frequent consumption of bitter tea clears the mind."22

Hujushi (壺居士) states in his Constraints on Food (食忌) that "Drinking bitter tea over a long time will make you as light as a bird. However, if you take tea with chives at the same time,23 you will gain weight."

Guo Pu's (郭璞)24 Commentary on Erya (爾雅注) says "Tea trees are like the gardenia. Its new leaves start budding in the winter. It can be cooked with starch to thicken it like a soup. Nowadays, people refer to leaves picked in the morning as "cha" while those picked at night are "ming (茗)". Another related term is "chuan", which is referred to as bitter tea by the Sichuanese."

One account collected in a famous book of anecdotes during the fifth century, A New Account of the Tales of the World, (世說新語) says, "Ren Zhan (任瞻) was a handsome prodigy who was famous from a young age. However, he had some difficulty adjusting to his new life after he fled to the South.25 When he was received by local hosts, they offered him a bowl of tea. He asked, 'Is this cha or ming?'26 He realized his question was awkward, since the hosts and other guests looked at him in askance. Then he tried to cover his ignorance and explained, 'I was asking if the drink was hot or cold.'"27

In the Sequel to In Search of the Supernatural (續搜神記), there is a story about someone called Qin Jing (秦精) who lived in Xuancheng.28 He often went to Wuchang Mountain (武昌) to pick tea. One time, he met a hairy man who was more than two and a half meters tall. The hairy man led Qin into the foothills of the mountain and showed him a great tea tree, leaving him alone there. After a while, the giant came back and reached into its belly and took out some oranges to share with Qin. Qin started to panic and fled home with the bundle of tea leaves he'd picked."

During the rebellion of the Four Princes, the Emperor Hui of Jin29 fled the capital. After the rebellion was pacified, upon returning to the palace, the eunuchs gave the emperor some tea in a pottery bowl.

Another fantastic account was recorded in Yiyuan (異苑), collected during the fifth century. "In Shan (剡) County, there was a widow who lived with her two sons. She loved drinking tea. Before she drank tea, she always offered a bowl to the ancient tomb in their courtyard. Her sons thought that since it was an anonymous tomb, it was a waste to offer tea to the spirit there. They decided to get rid of the tomb. However, the widow did not agree and after many arguments finally dissuaded them from exhuming the grave. She had a dream that night in which the spirit told her 'I have been here for over three hundred years now. Thank you for stopping your sons from disturbing my rest. And also, thank you for the fine tea. Even though I'm but dried bones under the ground, I must repay you for your good deeds.' The next morning, the widow found a hundred thousand dollars in the courtyard. The coins looked old, but the strings that strung the coins together seem new.30 The two sons felt ashamed and began to join their mother in making offerings and praying at the tomb."

The Hagiography of the Elders in Guangling (廣陵耆老傳) states that "During the reign of Emperor Yuan of Jin (晉元帝),31 there was an old lady who sold bowls of tea in the market every evening. She had a good business, serving many bowls, and yet her vessel never seemed to run out of tea. She would then give all she earned to the homeless and beggars in the streets. Some thought she was strange and turned her in to the authorities. The police took her to jail. That night, she flew out the window of her cell with her tea vessel in tow."

The section on art in the History of Jin (晉書藝術傳) was written by a monk named Shan Daokai (單道開) who lived in the western-most town in China, Dunhuang (敦煌). It says, "He often ate pebbles, medicine with the fragrance of pine, cinnamon, and honey. Other than that, he only drank tea."

The Sequel to Biographies of the Famous Monks (續名僧傳) written by the monk Daogai (道該) records that a monk named Fayao (法瑶) encountered a Daoist, Shen Taizhen (沈台真), and asked him to stay at the Xiaoshan temple in Wukang (武康小山寺). The Daoist was very old and spent his days drinking tea as the sun rose and set. When he was seventy-nine, the court sent an edict to the local official, summoning the old Daoist to the palace to be received with the highest honors.

Jiang's Family Genealogy of the Six Dynasties (宋江氏家傳) states that Jiang Tong (江統)32 was the attendant to the crown prince. He tried to dissuade the crown prince from doing business in the local market, arguing, "Selling vinegar, noodles, baskets, vegetables and tea in the market is a disgrace to us and to the country!"33

The Records of Sung (宋錄) documents that "Wang Ziluan (王子鸞) from Xinan34 and Wang Zishang (王子尚) from Yuzhang35 paid a visit to the Daoist Tanji (曇濟) at Bagong Mountain (八公山).36 The Daoist prepared some tea for them. Zishang tasted the tea and exclaimed, "This is ambrosia! Why did you refer to it as 'tea'?"

Wang Wei (王微)37 wrote a poem about a lonely woman:

Alone and desolate, I sequester myself in the highest chamber. Silent and empty, the grand halls. Waiting for my lord, who will not return, I resign myself and have some bitter tea.

Bao Zhao's (鲍昭)38 sister, Linghui (令暉), a poet in her own right, wrote seven Rhapsodies on Tea (香茗賦).39

Emperor Wu40 of the Southern Qi Dynasty's last edict was "No animal sacrifice for my spirit tablet. I only want cookies, fruits, tea, rice and dried meat." And he wished that this kind of modest funeral would continue on in later generations.

Liu Xiaochuo (劉孝綽)41 of the Liang Dynasty (梁) once wrote a thank-you letter to the Duke of Jin'an (晉安王蕭綱) for bestowing him rice and other produce. "Among the fresh and tasty gourds, bamboo shoots, pickled vegetables, dried meat, vinegar, fish, and liquor, the tea was the most beautiful and tasty."

A famous Daoist during the fifth century, Tao Hongjing (陶弘景)42 wrote that "Bitter tea will alchemize your bodily fluids, making you lighter. In the old days, Daoists like Vermillion Hill (丹丘子) and Gentleman of the Green Mountain (青山君) all drank tea."43

It is said in the Records of the Latter Wei (後魏錄) when Wang Su (王肅)44 from Langye area45 served in the South, he enjoyed drinking tea and thick, young lotus leaf soup (莼羹). After he went back to the North, he favored lamb and yogurt again. When others asked him whether he liked tea or yogurt more, he replied, "Tea does not even deserve to be the servant of yogurt!"46

A detailed account on tea was recorded in the most ancient anthology of herbs, Tongjun Caiyao Lu (桐君採藥錄). "People in Xiyang,47 Wuchang,48 Lujiang49 and Xiling50 like to drink tea with a thick froth. And they always offer tea to their guests. It is a delicious and fine beverage. In general, leaves are used to make the different kinds of drinks people consume. However, plants like asparagus (tianmendong, 天門冬)51 are pulled up by the roots and used to make herbal drinks, which are good for one's health. In Badong,52 there is a kind of leaf that resembles tea that can keep one awake all night. Also, people cook leaves of Chinese sandalwood trees (tan, 檀)53 with plums (zaoli, 皂李)54 as an herbal drink because these are considered cold in Chinese Medicine. As a result, this drink will cool down the body during hot summer days. In addition, there is another kind of plant that looks like tea but the leaves are very bitter.55 People often use the chopped leaves to make an herbal brew, which also can keep you awake through the night. People who produce salt for a living drink a lot of tea, especially in the Guangxi (廣西) and Guangdong (廣東) areas. Flavored tea is usually the first thing they offer to their guests."

The Journal of Geography, also known as Accounts of Kunyuan (坤元錄), written by a prince named Li Tai (李泰)56 states, "In Xupu57, the indigenous people gather at the peak of a mountain two hundred kilometers to the northwest of town, singing and dancing to celebrate their festivals. There are many tea trees on that mountain."58 Also, "Seventy kilometers east of Linsui, there is a brook called 'Tea'."

The Records of Wuxing (吳興記), written by Shan Qianzhi (山謙之),59 says that "ten kilometers west of Wucheng60 is a mountain called 'Wenshan (温山)'. The tea from Wenshan is tribute tea for the Dragon Throne."61

The Atlas of Yiling with Pictorial Illustrations (夷陵圖經) records that tea is made in the following four mountains: Huangniu (黃牛), Jingmen (荊門), Nuguan (女觀), and Wangzhou (望州).62

"There is a mountain called 'White Tea Mountain (白茶山)' about 180km east of Yongjia63" is a quotation from the Atlas of Yongjia with Pictorial Illustrations (永嘉圖經).

The Atlas of Huaiyin with Pictorial Illustrations (淮陰圖經) says, "There is a hill full of tea trees ten kilometers south of Shanyang."64

The account "Chaling65 literally means the valley with tea trees.", can be found in the Atlas of Chaling with Pictorial Illustrations (茶陵圖經).

In the Tree Section of The New Edition of Materia Medica (新修本草),66 it is recorded "Ming is a kind of bitter tea. It tastes bitter-sweet and is cool in nature. It is not poisonous, and works to cure sores, ulcers and warts.67 It is also a diuretic, moving stagnant phlegm and heat, quenching thirst and dispelling drowsiness. Tea leaves picked in the autumn taste bitter, and aid in relieving bloated wind and indigestion." As a result, there is an annotation in the commentary to this work that says, "Tea leaves should be plucked in the spring."

In the Herb Section of the same work, we find the following: "Bitter tea; alternative names are tu (荼), xuan (選) and youdong (遊冬). It grows in the valleys, riversides, and hills near Yizhou.68 The trees can survive cold winters. The leaves are picked and dried on the third day of the third lunar month." The commentary to this section says, "It might be called tea nowadays, but an alternative name is tu.69 It keeps people awake and clear. In the Classic of Poetry,70 the author exclaims, 'Who says tu is bitter?' and again, 'Tu from yellow soil is sweet as syrup', both quotes referring to this bitter herb. The bitter tea Tao Hongjing wrote of is also the leaves from this same tree, not some other herb. 'Ming' refers to tea picked in spring."

The famous Tang Dynasty doctor, Sun Simiao (孫思邈) provided a recipe in his text The Pillow Book of Cures and Prescriptions (Zhenzong Fang, 枕中方): "In order to cure chronic ulcers, one should roast bitter tea and centipedes together till they smell slightly burnt. Then smash them and divide into two equal parts. Cook one half with liquorice root (甘草)71 and drink it to flush the ulcers. Apply the other half to an herbal patch, covering the washed ulcers."72

There is an occasion that tea is used in Medical Recipes for Children (孺子方): "To cure problems with colicky children, cook tea with green onion roots and feed them the soup."

Notes

*The Erya is the oldest surviving Chinese encyclopedia.

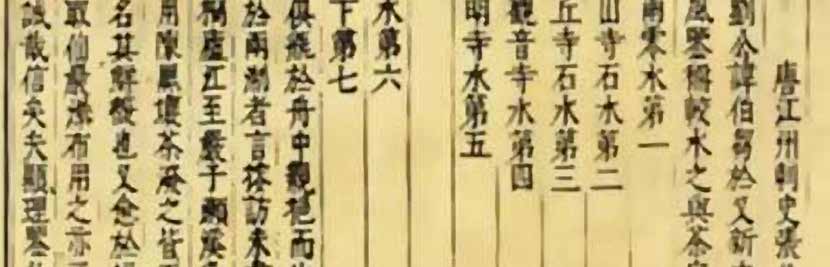

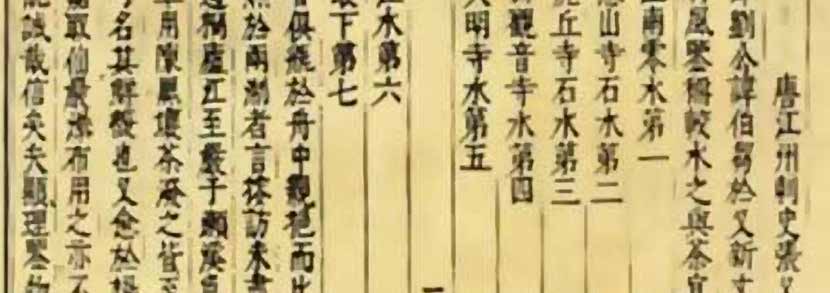

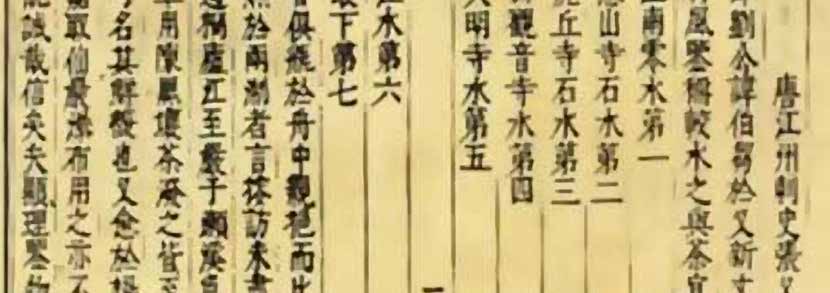

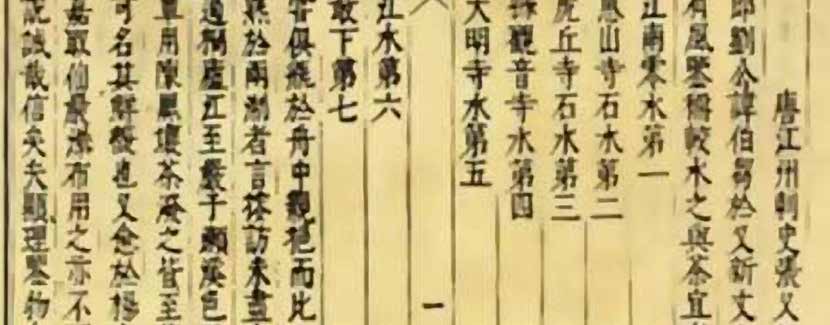

The grades and qualities of tea are:

In the Shannan Circuit (山南道)1 tea from Xiazhou2 is the best. Tea from Xiangzhou3 and Jingzhou4 are second. Then comes Hengzhou5; then Jinzhou6 and finally Liangzhou7.

Within the Huannan Circuit (淮南道), tea from Guangzhou8 is the best. Tea from Yiyang county9 and Shuzhou10 are second. Then there is Shouzhou11; then Qizhou12 and lastly Huangzhou13.

In the Zhexi Circuit (浙西道), tea from Huzhou is the best. In second place is tea from Changzhou14. Third is Xuanzhou15, Hangzhou16, Muzhou17, Shezhou18, and then Runzhou19 and Suzhou20.

Within the Jiannan Circuit (劍南道), tea from Pengzhou21 is the best. Tea from Mianzhou22 and Shuzhou23 are second. Then comes Qiongzhou24, Yazhou25, and Luzhou26. Meizhou27 and Hanzhou28 are the worst.

In the Zhedong Circuit (浙東道), tea from Yuzhou29 is the best. Second is tea from Mingzhou30 and Wuzhou31. Then, Taizhou32 is the worst in this circuit.

Within the Qianzhou Circuit (黔中道)33, tea trees grow in Enzhou34, Bozhou35, Feiahou36 and Yizhou.37

In the Jiannan Circuit (江南道), tea trees grow in Ezhou38, Yuanzhou39 and Jizhou.40

Within the Lingnan Circuit (嶺南道), tea trees grow in Fuzhou41, Jianzhou42, Shaozhou43 and Xiangzhou.44

I have not compared all the tea from the last three circuits extensively. However, what I did drink was mostly excellent.

Notes

During the Cold Food Festival (寒食節),1 one can pick tea leaves in the wild, or perhaps from a monastery, mountain garden or forest. After steaming and crushing them, they can be dried immediately and consumed within a short time. For such a small amount, some of the ordinary procedures and tools can be dispensed with. For example, puncturing the tea cakes (qi) or stringing them together (pu); or using an underground fire pit (pei), bamboo skewer (guan), wooden rack (peng), a tie of tea cakes (chuan), or a storage container (yu) are all not necessary.2

In terms of tea brewing utensils, if one brews tea in a pine forest and happens upon stones large enough for a man to sit upon, then a utensil rack will not be necessary.3 If one uses dried firewood and a tripod (cheng, 鐺),4 then there is no need to bring the brazier, its tray for ash, the fire tongs, bamboo tongs or folding stand into the woods.

If one brews tea along the riverside where fresh water is at hand, then the water containers for storing water and holding wastewater, and the purifying filter can all be left behind, as well. When there are less than five people at a session, and one can take more time to grind the tea into finer powder, then the sieve is not needed. If one wishes to drink tea while exploring mountain cliffs or caves, then one should roast the tea and grind it before embarking on the journey. The powder can be stored in the paper envelope or the round tea container (he). In that case, there is no need to bring along the heavy grinder or the feather for collecting tea powder. If all the utensils such as the ladle, bowls, bamboo stirring stick, hot water basin, and the salt container can fit into the charcoal basket (ju), than the larger bamboo basket (dulan) will not be necessary. However, when brewing tea in the city, within of the gates of the aristocrats, all twenty-four utensils and tools are needed to prepare fine tea.

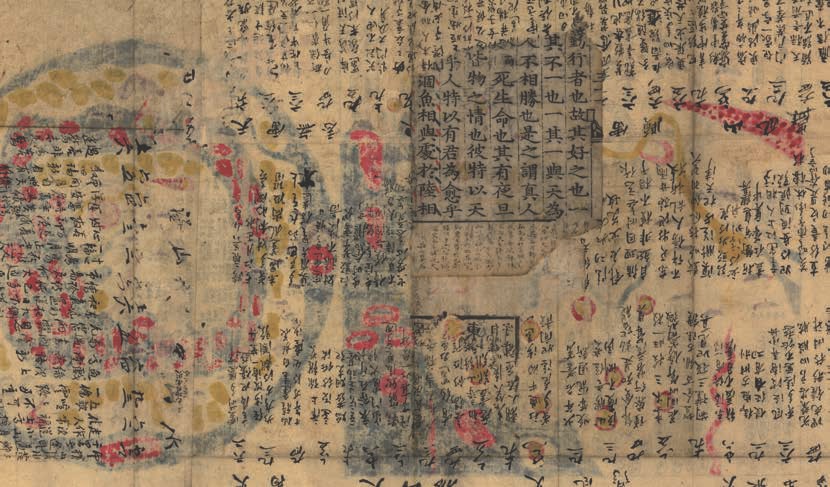

On four to six rolls of white silk, brush the nine chapters and mount them onto screen panels. The screens can be on display or tucked away in a corner when not in use. Take them out and arrange all nine sections so that they can be viewed together or individually, and thereby committed to memory. Open the screens for viewing when brewing or discussing tea.

Thus Ends the Tea Sutra By Lu Yu

陸 羽 茶 經