|

|

| "Cloud-hidden" (雲 深 不 知 處) |  | Ban Payase, Phongsali, Laos |  | Shou Puerh Tea |  | Khammu Aboriginals |  | ~1500 Meters |

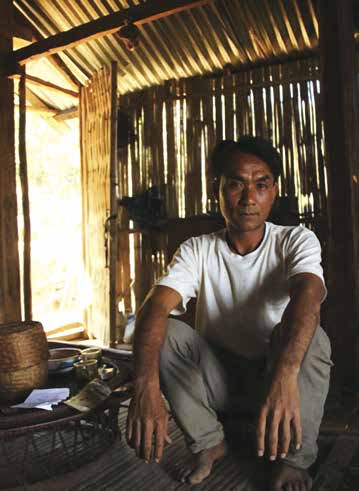

The old man can't speak your language, but his eyes welcome you into his small village home, darkened by the wood smoke that cooks his simple meals. His skin is dark and withered, cracked and crinkled like the folded hills you climbed back and forth on the long bus ride here. You can see all he owns; there's nothing hidden: a small bedroom, a small storage of rice, a kitchenette with an area for firing tea and bit of floor space for eating on mats. There's little distinction between in and outdoors - chickens wander in and out with dirty children, women gossiping in a sing-song language and visitors who drop by for some tea. The humans here live and breathe the jungle as much as the plants or animals, a part of the changing environment...

Tea regards no borders. People often argue about whether tea belongs to China, Japan or India; but tea belongs to Nature, paying no heed to the imaginary lines we draw on maps. There is such a thing as Chinese tea culture, but not the leaves. We can discuss a Chinese way of farming, a Japanese processing or Indian preparation; but the leaves are just leaves, born out of the Earth. This is most especially true of the wild, seed-propagated trees that are the origin of tea, and ultimately all tea culture as well.

Tea was born in the jungles of Southwest China, in Yunnan, Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam and a bit in India later on. They say the first Camelia sinensis evolved around a million years ago, which means that those old trees sat untouched and pristine for an eon before any human even noticed them - steeped only in dew, heated only by the morning sun, and drunk only be streams and rivers. And the seeds wandered the hills, each one a distinct soul like you and I. Like humans, tea trees are sexual and so each seed produces an entirely unique tree. Though they share a genetic heritage, as well as a similar climate which lends them resemblances, they are also all unique. This is why Tea has adapted to so many climates, for surely in one thousand seeds there is one which is suited to a new environment.

As tea moved east and north, whether naturally or carried by man, the trees adapted: The roots began growing outward rather than straight down and the leaves got smaller in colder climes. This has led some scholars to divide tea into large leaf trees, with bigger leaves, deep roots and a much greater longevity; and small leaf bushes, with wide roots and a shorter life span. In this modern age of industrial, plantation tea - rows and rows of bushes crammed so close together we can't see where one ends and the next begins - it seems almost too magical to imagine that the descendants of those first old trees are still living out in the pristine jungles of places like Yunnan and Laos.

The aboriginal tribes of this part of the world cross the borders often, and sometimes only speak their own local languages. In fact, the northern part of Laos was once part of China - Xishuangbanna to be exact - and was annexed by the French around the middle of the nineteenth century. As we said above, Tea doesn't mind our imaginary borders, invented cultures or pride; and sometimes we need to remember that Nature is bigger than our ideas. Drinking tea helps with that, especially amazing tea like this month's, which defies our borders and concepts.

On our first trips to Yunnan in the late 90s, we met tribal people that were completely self-sustained and cut off from all news of modern China. Nowadays, things are changing, and development is fast approaching this part of the world. A lot of that has to do with the growth of the puerh industry. In 1998, tea shops in Kunming (the capital of Yunnan) weren't specialized in puerh, and often suggested we buy green or red tea instead; and at the airport customs officials looked on our puerh tea with askance, not knowing what it was at all. Now, the airport itself is crammed full of puerh shops and Kunming has several huge and thriving puerh markets.

This development has, unfortunately, also reached the villages where much of the old-growth raw material comes from. As prices have risen, many villages have grown rich and others jealous. There is little regulation, leaving Yunnan prone to falsely labeled tea, tea switched from region to region, etc. Take for example the very famous tea from Lao Ban Zhang, which is the most expensive of all raw material (mao cha). The spring harvest in this village is only measured in a handful of tons, perhaps seven. However, in the big tea market of Southeastern China, Guangzhou, more than three-thousand tons of tea have some form of "Lao Ban Zhang" on the label. Are they blended? Are they fake? Are there magic elves that spin those seven tons into thousands before Rumplestilstea shows up?

Other problems have also found there way into the region with the moneys. Before this time, the aboriginal peoples there were mostly self-sustained. It is not entirely evident, therefore, that they spend wisely - often buying disco lights for their trucks, satellite dishes, cell phones and other things that herald the end of traditionally processed tea. Of course, they have also begun planting a lot more tea, and mixing the young with the old (sometimes even using agrochemicals). Young trees aren't always bad, depending how they are planted and cared for.

But all is not lost. The greater development in Yunnan has also brought information, foreign attention and more puerh lovers than ever before - people with an interest in preserving the jungles such tea is grown within. Trees are being leased and protected, and other promising projects are being created to maintain the living tea from this special jungle, the origin of all tea.

Traditionally, all the puerh that came from Laos, Vietnam and Myanmar was called "Border Tea". This was usually a derogatory term. Such teas were rarely pressed into cakes, and even today aged, looseleaf Border Teas can be had for much cheaper than the Yunnanese vintages. They say the trees aren't as good or the people there don't process their tea as well, but actually calling Border Tea inferior has always been more of a pride thing. Traditionally, people across the borders didn't specialize in tea as much as those in Yunnan, and sometimes didn't process it as puerh, which partially explains why it has had a lackluster reputation in the past.

Though the sense of pride continues today, and many puerh tea shop owners would tell you to steer clear of Border Tea, their dislike for it has lent it the very magic that makes it so special today: the mass-market of China - buying and selling thousands and thousands of tons of puerh - for the most part ignores this tea. This means that the jungles stay pristine, the cost stays low, the tea stays untouched and the aboriginals involved stay pure-hearted. Back in the day, everyone making puerh tea either did it because his father's father had or because she loved puerh. More than ninety percent of puerh producers, distributors and so-called "experts" have only been doing this for less than ten to fifteen years (since the boom) and only because they heard the jangle of coins in others' pockets. But across the border, in the remote jungles of Laos, you have a better chance of finding an old farmer who honestly loves tea - a farmer like Insay.

Insay has two gardens where he grows and harvests tea. Behind his hut there is a tea garden with old tea trees up the hill. Usually his wife and his son harvest tea there. But they don't make tea at home, they take it up the mountain on the motorcycle, it takes ten minutes to drive up the slope, which is a narrow and dangerous mountain path. On the southern slope of the mountain there is the second tea garden and a tea hut, where Insay withers and fires his tea.

The tea hills in Ban Payase are very beautiful and harmonious, a place you always want to come back to. Insay was discovered by some Russian tea lovers seeking to find pure, wild, old-growth puerh. As we've said - it's worth repeating - the Phongsali Province of Laos actually was once a part of the kingdom of Xishuangbanna, and therefore a part of "Yunnan", until the eighteenth century when it was taken from China to join French Indochina. This is why there are threehundred- to four-hundred-year-old trees throughout the area, like those Alexander found in the village of Ban Payase. The trees of this part of the world have ho-hummed as the borders have changed, and sighed when people called them "Chinese" or "Laotian". One wonders, then, if this really is "Border Tea" in a different sense.

The village of Ban Payasi is 1500 meters above sea level in the most rural of all Laotian provinces, Phongsali. It is so remote that the Buddhist religion has much less of a hold on the tribal people here, who still practice their native shamanism. Unique tea plantations of large old tea trees have been safely preserved. The climate here is perfect for growing tea: cold foggy winters and warm rainy summers. The capital of this Province, also called Phongsali, lies on the slopes of Mount Phu Fa (1625m above sea level). Getting here is quite difficult as the whole area is far from any paved road or airport. Most people use the local river for transportation. The trip usually takes three days - one way. Because of the isolation, people in Phongsali have a simple and natural life style. In this beautiful and ecologically clean environment wonderful tea is produced.

It was here that Alexander found a true lover of tea, caring for old and young-growth trees with equal love and affection. Our tea is a blend of the younger, forty-year-old trees and the older, three-hundred-year-old ones.

Alexander and his partner Timur formed the Russian tea company Tea Pilgrims, Ltd. to promote organic, local tea to Russia and the world. They graciously donated this month's tea, which you will find to be a pure example of what "living tea" can be - and in a shou puerh nonetheless! "Living tea" is a term we reserve for tea that is seed propagated; organic, sustainable, and allowed to grow up old and strong; with room between plants and a healthy relationship with the surrounding ecology, no irrigation and, of course, no agrochemicals. When you drink a living tea, you know it, as you will find this month for sure. Monoculture inhibits tea in so many ways, as it does most any plant species. It is impossible for us to understand or measure the infinite relationships a plant has to its local ecology: the other plant and wildlife that surrounds it.

It is very difficult to find nice, intentionally produced shou puerh these days. Most shou is made from a smattering of what is left over after sheng cakes are made, and of lesser quality raw material (maocha) since puerh is expensive and there is a loss of quality and essence in the piling, and since no one would pay sheng prices for shou cakes. "Cloud-hidden," as we call it, is one of the best shou teas you will ever have, with billowy, expansive energy that fills you up and opens all the pores. This tea leaves you tangled up in the sky, with no direction home. Enjoy a deep session with some amazing people and help us celebrate this amazing, growing community!

Asked the dream boy Where he'd gone. Was he always cloud-hidden, lost to the touch? But the landscape shifted, drifted away, before he could answer we were both wind and clouds.

We recommend brewing this shou tea strong. One of the things we love about tea like this is that it is very forgiving to brew: it doesn't matter if you put too much or too little leaves, steep it too long or too short. Other teas, like Cliff Tea or other oolongs require a bit more finesse to brew. But shou puerh is nice strong or light. Still we recommend putting a bit more in the pot than usual. This is a more lightly-fermented shou that was intentionally stopped, without being piled the usual forty-five to sixty days.

We drank this tea in a side-handle pot using bowls. If you have never brewed tea in that way, you should check out our video on YouTube. This is a great way to hold a bowl in the spirit of "just leaves, water and heat" but also steep the tea, as not all kinds of tea can be put directly into the bowl. This shou, however, has more intact, longer leaves because it wasn't fermented as long as most shou teas. This means that you could actually put the leaves directly into the bowl, which is something we plan on experimenting with ourselves.

Notice how the warmth spreads outward from the chest and stomach. This is where puerh enters the subtle body. For that reason, it is better drunk from larger cups, or bowls, and in big gulps. Oolong, on the other hand, enters the subtle body through the head (aroma/air) and is therefore better drunk from small cups, with the smallest possible sips. Try taking large sips to facilitate the Qi in your chest/stomach. Enjoy the warmth, especially if you live somewhere that is growing cooler day by day.

Shou puerh like this requires a lot of heat. The hotter your water, the better. Having tried our gongfu experiments concerning temperature, you'll know the importance of heat in gongfu brewing. This is even more essential when it comes to shou puerh like this.