|

|

The pleasant aroma that arises from a properly brewed pot of tea was perfectly brushed into words by the monk Chao Quan (超全, 1627-1712): "As with the plum and orchid blossom, a slight fragrance begins to rise when tea leaves are steeped. Like the slow heat of the coals that roast the tea leaves, the masters take the time to hone their craft in glowing precision."

Among the seven kinds of tea, oolong requires the most craftsmanship to produce. As a result, it is the most complex and profound kind of tea, at least as far as depth of flavor goes. It can be as challenging to brew as it is to produce. However, when prepared properly the "gem of tea," as it is called, offers a subdued "plum or orchid blossom" fragrance that can be transcendent. The unique floral or fruity aroma differs depending on the variety of tea, weather conditions, season of growing and picking, and the roasting process. There are, indeed, many facets to this gem!

Compared to other kinds of tea, oolong also has the greatest variety. As a semi-oxidized tea, it is a combination of the briskness of green tea and the mellowness of red tea. In addition, different varietals, environments and climates, as well as different processing methodologies, all influence the taste and aroma of the finished tea. There is truly a wide spectrum of different oolong teas, each with its own rich heritage, flavor and fragrance! It is, therefore, no simple task to write about oolong tea.

Oolong can refer to a varietal of tea tree or the process of semi-oxidizing tea. Tea categorization is complicated, and so defining tea purely by processing is misleading. There are four major kinds of oolong tea, distinguished by the places they are from: Wuyi Cliff Tea (武夷岩茶), Anxi Tieguanyin (Iron Goddess, 安溪鐵觀音), Fenghuang Dancong (鳳凰單欉) and Taiwanese oolong. This article will focus on Taiwanese oolong, exploring its history, craftsmanship and the development of different kinds of oolong tea in Taiwan over time.

As an island on the Tropic of Cancer, Taiwan has a warm and humid climate, with steep and high mountains. Such a rare combination makes it an ideal environment for growing tea. In addition, seventy percent of Taiwan is mountainous, so there is a vast area for tea farming throughout most of rural Taiwan. The tea industry sprouted in the 17th Century when the Chinese started to migrate to Taiwan and then bloomed into an international flower during the Japanese occupation, from 1895 to 1945. Since beginning the now-famous annual tea competitions in the 1960's, Taiwanese oolong has changed radically. Recently, for example, economic ties between Taiwan and China have become possible again, and this has had a huge impact on tea production and sales in Taiwan.

First of all, it is important to remember that what we call "tradition" now was an innovation in the past. When did oolong tea begin? And what innovations and transformations has it been through along the way? The earliest record of oolong tea can be found in On Tea (茶說) written by Caotang Wang (王草堂 ) in 1711. "People pick Wuyi tea leaves between the guyu (穀雨) and lixia (立夏) solar terms.1 Since guyu is the first solar term in the spring, this tea is then called 'the first spring tea'... They spread the tea leaves evenly over shallow bamboo trays and stack the trays on racks under the sun to wither. This process is called shaijing (曬菁). When the leaves have lost their green color, they are then ready for drying. The flat 'Jie' tea from Yangxian (陽羨), Jiangsu (江蘇) is not fired at a high temperature; it only goes through steaming over a low fire.2 On the other hand, Songluo (松蘿) and Longjing (龍井) are fired at a high temperature while the leaves are stirred vigorously. As a result, the shades of all three teas mentioned above are closer to one another. Wuyi is the only tea that goes through both high and low temperature firing. Therefore, some leaves are red while others are green. The green leaves are baked over a high fire while the red leaves are baked over a low fire..." This account is obviously a bit different from how Wuyi Cliff Tea is produced today, and in some ways difficult to decipher without seeing the tea, but gives us a historical reference from the very beginning of oolong production.

Oolong tea first arrived in Taiwan around 1810. The Chinese brought seeds from Wuyi Mountain and propagated them in what is the modern day Ruifang area (瑞芳), New Taipei City. Since then, oolong tea production has spread widely throughout Taiwan. After several transformations in the tea industry, Taiwanese oolong tea began to flourish, becoming famous internationally.

In 1869, Taiwanese oolong tea began to be exported to the US and became renown there as "Formosa Tea." Later in the 1920's, a more heavily-oxidized tea called "the Beauty of the East (Dongfang meiren, 東方美人)," was created with a unique fragrance and a stunningly beautiful color. Around the same period, Shuijin Wang (王水錦) and Jingshi Wei (魏靜時) revolutionized oolong processing when they invented the subtle and very aromatic Baozhong tea of Northern Taiwan. Skipping the withering process and moving directly to oxidizing while stirring and firing lends this kind of tea a unique floral aroma.

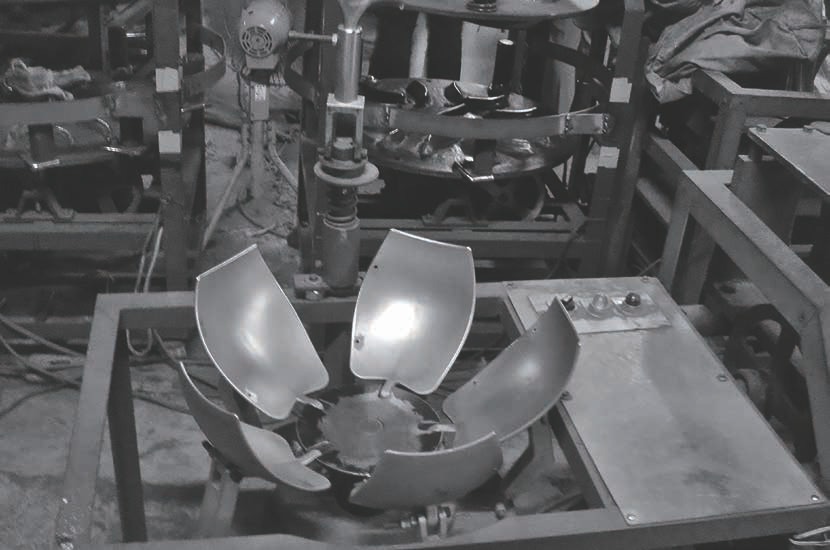

Two expats from Anxi, Youtai Wang (王友泰) from the Fuji Teashop in Taipei and De Wang (王德) introduced the cloth-rolling technique from Anxi - the traditional way of making ball-shaped Tieguanyin - to the tea industry in Minjian, Nantou. Later, that processing methodology moved to Dong Ding, Lugu. Eventually, this cloth-kneading technique was employed in other areas of Taiwan, starting in the 1970's, slowly taking over the Taiwanese tea industry. Today, Taiwan is most famous for ball-shaped oolong tea. For a long time, all the ball-shaped oolong was processed much like Anxi Tieguanyin, with higher oxidation and skillful roasting. And Dong Ding was at the center of this.

黑 龍 飛 昇 數 百 年 延 綿

The first tea competition was held in Dong Ding in 1976. The judge, Zhenduo Wu (吳振鐸), who was the director of the Tea Research and Extension Station in Nantou, awarded first prize to a tea that combined the floral aroma of lighter Baozhong teas with the richer flavor profile of Tieguanyin. This historical decision brought together the two major tea processing methodologies of oolong tea in Taiwan. One is the new formula, which has taken over the mainstream, using lighter oxidation and roast. The new variety of "high mountain oolong" also employs this processing, and has won over a huge segment of the tea market. The traditional way of making oolong with a rich flavor, warm taste and a red-brick hue of liquor slowly became the minority in Dong Ding, as farmers met the demand for lighter, greener oolong teas. In the beginning, many of these lighter teas were amazing, and some still are, so the innovation itself was genius at the outset. And when it is done well, such light tea can still be marvelous even nowadays.

Besides what can be seen as brilliant innovations in tea production, the 1970's were the golden era of tea in Taiwan. The economy took off during that period and the prospering tea industry helped facilitate a thriving bush of tea aficionados, ceremonies, gatherings and tea culture that continues to blossom even today.

Over the past four decades, ever since the first time a greener tea won the most famous of all competitions in Taiwan, the annual Dong Ding tea competition, tea in Taiwan has become known as a light green oolong tea, with a faint suggestion of the tea it once was. Tea liquor with a rich, complex and yet subdued aroma is what ancient and modern poets lauded in a fine oolong tea. However, it is very difficult to produce in large quantities. Not only is such tea an acquired taste, usually of the more seasoned drinker, but its production also requires a lot more skill and technique. It takes a very long time to learn these skills, let alone to master them. When you add to that the skills needed to brew such tea well, you can see why the industry moved towards lighter, easier to make and brew teas. Furthermore, not many people can withstand the hardships of artisanal tea farming, especially during the harvest when producers will hardly sleep for weeks at a time. Quoting On Tea again, "When it comes to guyu, it is a hustle and bustle in places where tea is grown. During those two weeks, most people hardly have the time to eat or sleep."

Due to the short window of plucking time for spring tea, a lot of farmers started picking younger leaves. Unfortunately, the success rate with the fresh buds/leaves is not that high. Also, while the cost of living has risen, the price of oolong tea has not grown in proportion over the last thirty years. As a result of all these factors, tea farms in Taiwan have increasingly switched to plantation models, allowing machines to replace handmade tea skills for the sake of profit. And local tea growers were slowly bought out by big companies...

In the end, the subtle aroma of fine oolong has been swallowed by the void of mass-produced tea that lacks a real, lasting fragrance or body.

Like waves on the sea, when any given trend reaches its highest point, another will certainly rise behind it and take its place. After decades of light-green oolong dominating the market, people have started to miss the special aftertaste of traditional oolong. After one sip of traditional oolong tea, one feels a pleasant, sweet aftertaste that stirs the memory. If one savors this aftertaste, it's almost chewable, like substantial food. In addition, such tea causes more salivation and hence quenches one's thirst quicker and more fully. As a result, searching for the obscure "red-liquor" oolong has become a new trend.

This so-called "red-liquor/water (紅水)" oolong is nothing but a vague term actually. In fact, the color of traditionally processed oolong is not really red. This phrase was coined by the mainstream tea industry to separate such tea from the light liquor of the more popular greenish oolong. Still, the phrase does have historicity, tracing all the way back to 1896. At that time, Taiwanese tea was made in the same manner as Wuyi tea, withered lightly, shaken and then roasted over high-temperature coals. The quality of such oolong is determined largely by the roasting process, and the tea is rich in flavor, with a savory aftertaste.

As tea moves to new mountains, it changes. Terroir is everything in tea. And as a tea varietal is changed by and through its new environment, farmers will also adapt their processing and culture accordingly. This is how all tea production develops. Similarly, the Wuyi varietals brought to Taiwan also changed, and so did their processing. In 1921, two new Baozhong roasting techniques were invented in Taiwan by Jingshi Wei in Nanggang and Shuijin Wang in Wenshan. In comparison, Wang's style originated from Wuyi tea and the liquor looked more like shiny red ochre than Shuijin Wang's, which was greenish in color. As a result, during the first half of the 20th Century, people used "red liquor (紅水)" to refer to the Wenshan Baozhong as opposed to the Nangang green roasting.

The late Ye Ji (季野) , the most famous tea connoisseur in modern Taiwanese history, created a controversy in the 1980's by insisting that the "red liquor oolong" is in fact true traditional Dong Ding oolong. As a result, many tea stores and tea fairs followed Ye Ji's point of view, and labeled traditional Dong Ding oolong as "red liquor" oolong in order to differentiate it from the greener and lighter oolong tea on the market. On the other hand, the tea farmers and tea makers in the Dong Ding area were strongly repulsed by the term "red liquor/water." In their experience, when they made mistakes in the roasting process, especially when making lighter/greener/less-roasted oolongs, the liquor would turn reddish. To them, the term "red liquor" referred to mistakenly processed, downgraded tea. Therefore, the local tea farmers preferred to call tea produced with higher oxidation and roast "traditional oolong" rather than "red-liquor/water" oolong.

There is perhaps a less controversial and more poetic interpretation of calling traditional oolong "red." Earlier I mentioned that traditional oolong liquor isn't exactly red, which is true. Like most teas, it is actually a spectrum of colors from red in the middle to orange, gold and yellow at the rim. The epitome of traditional oolong is that it be "red in the heart," which is a reference I found even in old tea literature. It referred to the otherworldly brew of tea leaves that were roasted to perfection. As tea expert Zhu Chen (陳助) says, "when the tea is aromatic inside and out from the bones and marrow, it does not separate, even if you cut it with a knife." Therefore, the reddish color referred to by the now-common term "red liquor/water" does not necessarily refer to heavier fermentation or roasting, nor is it due to excess humidity in storage or the misprocessing of tea, as the farmers would use the word. It could perhaps refer to oolong tea that is roasted magnificently - to the red marrow.

Traditional "red liquor" cannot be clearly defined - different people mean different things when they use this phrase; everything from a mainstream kitchen drinker who doesn't really understand what they are saying other than that this tea is "darker" than what they are used to all the way to farmers who mean tea that is misprocessed. When it was coined in the 19th Century it clearly referred to the tea produced in a specific area of Taiwan. In some ways, the ambiguity of this term is the perfect lens to reflect on the complicated world of oolong tea, and is therefore worthy of so much of our attention.

The defining characteristic of oolong tea processing is that it is semi-oxidized. By bruising, yet not completely destroying the cell walls of the leaves during the withering and shaking stages of oolong production, the cells will oxidize partially. The degree of "partiality" in this most-complex of all tea production is the key to the huge variety of unique aromas, flavors and tastes in the world of oolong tea. Over time, as more and more innovations and changes have come, the range of oxidation in oolong has also grown, and so what was already a complex genre has grown even more complicated over time.

As we mentioned at the outset of this article, Taiwan is rich in flora because of its mountains and semi-tropical/tropical climate. It is not difficult to find a great place to start a tea farm in Taiwan. As farmers learned the natural environment and weather conditions, they then tried many variations and production techniques, choosing the best way to dry the tea leaves grown on their own farms.

Tailoring processing to the qualities of the tea leaves is the hallmark of skillful tea production, and a renewal of this trend is growing in the tea industry these days. Years ago, a farmer who made traditional "red liquor/water" oolong, when the market was dominated by green oolongs, was laughed at by all the other tea farmers and sellers. Nowadays, more and more farmers are producing such tea, and the skills required are garnering respect again.

We hosted three "Asia-Pacific Oolong Tea Conferences" from 2011 to 2013 to promote traditional "red liquor/water" oolong. In order to get back to the time when fine oolong tea didn't need vacuum-sealed packaging, or the machinery and waste that part of the industry creates. There was a time when all tea was wrapped in paper. Traditional charcoal roasting stabilizes the tea leaves, and so vacuum sealing wasn't necessary back in the day. We sought to re-popularize such traditional tea making skills. Therefore, we gave out authentic, traditional "red liquor/water" Lishan oolong in 4 oz. paper packs without vacuum sealing as souvenirs to those who attended these gatherings. With the success of these events and the tea, we hoped to demonstrate the possibility of a heritage revival, hoping that Chajin would enjoy reminiscing older, and maybe better times.

Another new and exciting trend is that "red liquor/water" or "traditional" are no longer phrases reserved for traditional tea processing trends in Dong Ding anymore - the movement has spread throughout Taiwan. Between tradition and innovation, the key to a better balance probably lies in the National Farmers Association, which has controlled the reputation of many kinds of tea in Taiwan for several decades by holding tea competitions that many farmers, producers, shop owners and aficionados respect. As long as the judges and NFA associates are just, meaning that they are not influenced by financial relationships with the farmers and there is no money involved, the tea industry will be freer and thrive. If such mainstream organizations begin to support and promote artisanal, handmade, traditional teas, along with lighter oolongs, the trend towards better tea will get a huge boost. And there are hints that this is coming!

Influenced by the new economic ties with China, the Taiwanese tea industry is also facing more Chinese competition. It will be difficult for Taiwan to compete with Chinese machinery, price or mass-production. The mainstream tea drinker in Taiwan will now have access to cheaper, more consistent varieties of Chinese oolong. For that reason, one could argue that one ideal strategy for competing with this would be to hearken back to traditional experience and skill, aiming to make a niche in the larger international market by reviving heritage. We should rekindle the warmth of conventional craftsmanship and tea roasting skills and aim to leave the cold machines out of the photos taken these days - photos that will one day hang on the walls of future tea lovers to characterize this era of tea production. Returning full circle to the beginning of this article, we remember that the monk Chao Quan alluded to the intricacy and subtlety of tea four hundred years ago. As a Taiwanese Chajin, I hope the skilled tea makers with the expertise in roasting will unveil the charming subdued blossom-like fragrance of Taiwanese oolong tea to those who raise a cup four hundred years from now!