|

|

You may be surprised to learn that red tea is the most popular type of tea in the West. How is it that most Westerners drink red tea without ever having heard of red tea? Simple. It just isn't usually known by that name in the West.

In China, where red tea originated, it was (and is) known as Hong Cha (literally, "red tea"), after the reddish color of its infusions. However, early in the tea trade to the West, very little information was exchanged when the tea was handed over for silver. Even things like teas' names could be (and often were) terribly misunderstood or mangled in those days. And so it came to be that the name red tea was dropped in favor of "black tea," which referred to the dark, withered leaves of the tea. (After all, these already dark leaves were likely made even darker by the long and salty boat journey from China to Europe and to America.) Therefore, a large part of the confusion came from the fact that the Chinese tended to differentiate tea based on the liquor, whereas Westerners looked at the leaf itself. The name "black tea" stuck in the West, but in recent years there has been a shift toward more tea awareness and the spread of the term "red tea."

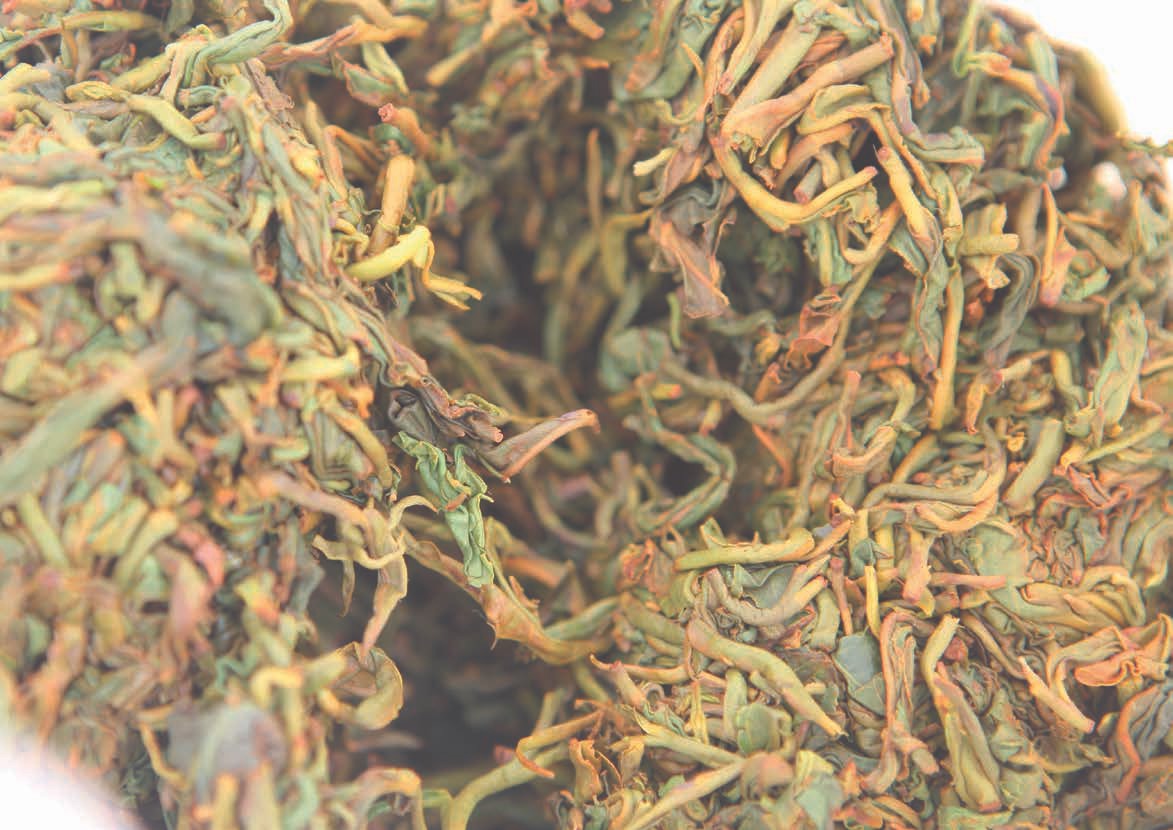

Unlike other tea types, red tea typically has leaves that dwell in the red-to-black range of the color spectrum. This includes the muted orange of Dian Hong, the deep rust of Assam Second Flush, the greenish-black of Darjeeling First Flush and the blue-blacks of many Keemun and Ceylon teas. Regardless of the color of the leaves, though, the infusion is typically dark and warm in color, i.e. deep tan, rust red or espresso brown. The colors of red tea infusions and leaves (which resulted in the names "red tea" and "black tea," respectively) are both primarily the results of tea processing.

As we've explained in previous issues, different kinds of tea are processed differently. While processing is not the sole differentiating factor (varietals, terroir, harvest seasons and many other factors can make substantial differences), processing often has the most profound effect on how the liquor will look, taste and feel by the time it reaches your teapot or bowl.

Oftentimes, Western authors mislead us by saying that all tea is the same plant and only differs in processing. Actually, of the seven genres of tea, this is really only true of red tea, which happens to be the most consumed tea in the West, which helps explain some of the confusion. The other six genres of tea are as much a varietal as they are a processing methodology. But you can process any tea as a red tea, and usually with nice results.

Long ago, all semi-oxidized tea was called "red tea." There really wasn't a demarcation between oolong and red tea, and Chajin used the terms interchangeably. Red tea was just the final stop on the semi-oxidized line. Though red tea is sometimes called "fully oxidized," that really isn't possible; but it is more heavily oxidized than any other genre of tea. Because it has more processing and more oxidation, red tea is stronger. The leaf has had more of its essence opened up. Even chemically, it has more tannins and caffeine, and is therefore more brisk and uplifting than all the other six genres of tea.

Red tea processing generally follows these steps:

You may have noticed that three of the eight steps above involve oxidation. Heavy oxidation is the main differentiating factor between red tea processing and other types of tea processing. It is what brings out the deep colors and the aromas and flavors of fruit, malt and tobacco leaf in red tea. It's also a factor in red tea's relatively long shelf life.

There is some overlap between tea types with regard to oxidation. For example, a heavily-oxidized oolong such as a traditional Wuyi Cliff Tea may be considered to be an oolong in China and a red tea ("black tea") in the West, while a lighter oxidation red tea from Darjeeling or Nepal's first flush (spring harvest) may be thought of as akin to an oolong. However, oolong tea entails several steps that are not utilized in red tea production, like shaking to bruise the edges of the leaves, for example, differentiating it from red tea despite the occasional similarity in oxidation levels. Therefore, while oxidation is a key difference between red tea and other tea types, it is not the sole difference.

The Ming Dynasty saw many developments in tea processing, including oolong tea, flower-scented tea and red tea. Later, in the Qing Dynasty, many of the teas developed during this age of innovation were evolved further.

As with any timeline detailing groundbreaking developments, there is some controversy over when the "first" red tea appears. Accordingly, there are several origin stories about red tea. Some claim that the appearance of Wuyi Cliff Tea (also known as "Congou black tea" in the West, and as we discussed above not really a red tea at all) in the 15th or 16th century heralded the age of red tea, while others credit it to the appearance of Xiao Zhong ("Souchong" in the West) in Fujian around 1730 or to various red teas that were developed in Qimen in the 1700s. Later, around 1875, the technique for making Gongfu Hong Cha was introduced to the Anhui region, a major producer of Qimen ("Keemun") red tea to this day.

Ultimately, which tea was the first red tea didn't matter much to the local tea drinkers of the time - in general, red tea wasn't very popular with them. However, starting in the early 1800s, the import markets in Europe, the American colonies and the Middle East couldn't get enough red tea. Some attribute the international popularity of red tea in particular to red tea's shelf stability (a necessity in long ocean journeys), while others say that it has more to do with the compatibility of the bold flavor profiles of red teas with the cuisines of Germany, England, France and other nations where red tea has become the default tea type.

It was this popularity that led to large-scale production of red tea in China, and to the eventual theft of tea seeds, tea plants and tea production techniques, which were taken by Scottish and English adventurer-entrepreneurs and transplanted to India and other colonial territories (such as modern day Sri Lanka and Kenya). These entrepreneurs took their limited knowledge of tea production and used it to fashion machines that replaced the handmade aspects of tea processing. The availability of cheap red tea fueled its popularity as a tea type further, making it the most popular category of tea in the West to this day.

Today, red tea is produced using this machine-driven approach in many countries, including Brazil, India, Indonesia, Rwanda, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Vietnam. More recently, machine-made red teas have appeared in Japan (where they are called wakocha or "Japanese red tea"), and machine-made red tea has even made its way back to China.

Meanwhile, green tea and oolong remain the most popular types of tea amongst tea drinkers in China. However, in recent years the interest in handmade and more traditionally made red tea has seen a resurgence in China, Taiwan and elsewhere, resulting in a wider availability of handmade red teas from China and Taiwan (including our Tea of the Month). For this and other reasons, the characteristics that red tea drinkers in China and Taiwan prefer tend to be different from the typical tea drinker in the West. Instead of looking for a dark color in the infusion or boiled liquor and a bold flavor that can handle milk and sugar, these tea lovers seek out beautifully shaped leaves and infusions that are best savored without any additives. Also, while most red tea drinkers steep their leaves only once, those opting for more traditionally made red teas prefer to let the leaves open up gradually with many short infusions, savoring their tea patience and their inner spirit rather than gulping them from a to-go cup while eating a pastry on the way to the office.

Fortunately, this newfound appreciation for more traditional red teas is spreading beyond China and Taiwan. It is our hope that you will be able to further your own growing appreciation of red tea with this month's Ruby Red, and to perhaps even spread the love for red tea in general.