|

|

Not so long ago, puerh was usually brewed with chrysanthemums and enjoyed as an accompaniment to meals. But ever since people began putting it into small purple-sand Yixing pots used for brewing oolong tea in a gongfu style, its standing in the tea world has skyrocketed. Over the past two decades, the mainstream has begun to find puerh palatable enough to be had on its own, without the accompaniment of food. More recently, Taiwanese tea drinkers have begun a new experiment using the gongfu brewing style in small pots to brew red tea. As a result, we see that so-called "Gongfu" (made of small leaf, all-bud teas from Fujian that require more skill to process) and "Souchong" red teas, usually intended for export, have found their way into the connoisseur tea market. (Souchong is a varietal of red tea from Wuyi, Lishan Xiao Zhong in Mandarin, which literally translates to "a varietal from Lapu Mountain." It is known for its smoky taste as the tea was originally withered above people's cooking fires and took on the flavor of pine smoke. Nowadays this scenting is done intentionally.)

The gongfu brewing method is a mainstay of traditional tea culture; it is also the "orthodox" way to drink oolong tea. The teapot, which once played a supporting role, took center stage in the Ming Dynasty after the issue of an imperial decree that banned powdered tea in the form of cakes that were ground and roasted. Five hundred years of cultural development has fixed the teapot's place in the tea lover's heart, so that now it is an essential part of tea drinking around the world. This development naturally led to the introduction of gongfu tea culture, which in turn formed the gongfu tea industry and its characteristic method of tea-drinking. The manufacture of teaware has changed much from the era of tea cakes ground into powder, reflecting a remarkable shift in tea-processing infrastructure, the art and appreciation of teaware and, of course, the way that tea is prepared and shared.

Gongfu preparation was originally developed to brew oolong, which abounds in variety. Semi-fermented tea is roughly dividable into Taiwanese oolongs, Tieguanyin, originally from Anxi, Narcissus teas from Phoenix Mountain and Wuyi Cliff Tea. This kind of tea, and tea preparation, was therefore originally a local culture. Teabags, at the other extreme, are a distinct product of international commerce.

Before the global economy took shape, the only teas available in Mainland China were green and red teas. Green tea production goes back thousands of years. "Red tea" was the term applied to all semi-fermented teas in general, and also denoted the teas produced in the Fujian region.

The duration of oxidation determines the color and flavor of the tea. Leaves that are given no time to oxidize will be green after drying, whereas leaves that are allowed to oxidize will be a reddish color. Obviously, the green leaves are called "green tea," and the reddish ones "red tea." The length of the oxidation period determines how deep a color the leaves will have. Arresting oxidation through steam was perhaps the most ancient method. Firing tea, according to Luo Dan's The Origins of Wuyi, was an improvement upon the tea processing methods of Anhui Province, introduced in 1395 AD. As for "red tea," which, remember, once referred to all semi-oxidized tea, including what we call "oolong" today, in Wang Caotang's 1717 Discourse on Tea we find the following record: "After rolling, Wuyi tea must be exposed to sunlight, spread out on a surface, raked, and then stirred when it begins to emit a fragrance." In An Anthology of Petty Matters of the Qing, Xu Ke of Zhejiang Province (1869-1928) gives a clearer and more complete record of green and red tea processing:

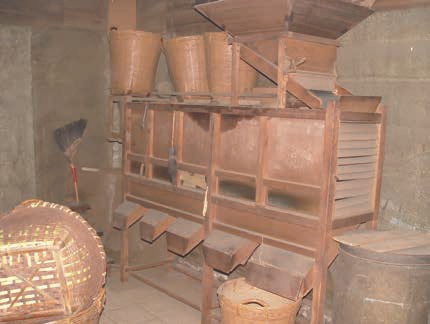

Green Tea Processing: Place the tender, rolled leaves in a basket for steaming, or in a cauldron for stirring. When the leaves become sticky and fragrant, remove and spread them out on a flat surface. When they have been cooled, place the leaves in an oven, rolling them as they are baked so that they are allowed to dry gradually. Transfer them to an oven heated by a weak flame, turn and roll them until they are totally dry. This completes the process.

Red Tea Processing: This tea is a produced in the Fujian-Guangdong region. When the fresh leaves have yellowed under sunlight, place them in a trough, roll, then transfer to a large cauldron, firing until wilted. Cover with a piece of fabric, allowing the leaves to ferment until red; dry them to complete the process.

After the fifteenth century, the rise of a global economy left radical changes in its wake, as foreign merchants took tea to Europe. In 1607, when the Dutch sold Chinese Wuyi tea for hundreds of times its price in China, they opened the door to an export market that would last for centuries to come. Records from the reign of Emperor Xuan of Han detailing a domestic tea market date back to 59 AD. 1,688 years later, this regional product, considered lowliest among the "Seven Domestic Necessities," became the main focus of a new global economy. The enormous profits and commercial opportunities it ended up creating went far beyond anything the feudal rulers of the preceding thousand years could have imagined.

The Dutch discovered Chinese tea, but it was the British who popularized it. By 1669, the competition between the British East India Company and the Dutch East India Company for control of the tea market was in full swing. Then, in 1721, the British obtained exclusive purchasing rights and began exporting up to one million pounds of green and "black" tea a year. (Here, "black" tea refers to oolong and red tea, which the British called "black" tea on account of the dark color of the leaves.) The long time spent at sea affected the tea's quality. The British eventually issued laws against imitations and substitutions, while also devising some way to produce tea for themselves. In 1780, having obtained a quantity of the much-sought-after tea seedlings of Guangzhou Province, the British began their largescale tea cultivation operations in India, then later Java and Sri Lanka. According to William Ukers' All About Tea, in 1830, George James Gordon successfully innovated upon Chinese tea-processing by effectively simplifying the complex and difficult oolong-making procedure, which yielded Indian red tea of a highly consistent quality. In 1855, the British invented the mechanical tea cutter and tea mixer in response to the demands of red tea production, followed by the tea roller in 1872 and the tea dryer in 1874. Such a proliferation of machines to aid in tea production indicates that they saw manual labor as inefficient, and sadly began its decline. As the market in China began to shrivel, so too did the two-centuries-long tea boom that had flourished there - another change that gave rise to more changes...

In the wake of oolong's decline, as it was included in the fall of Chinese and Taiwanese "black" tea, Baozhong tea came to the fore. Taiwan began producing Baozhong in 1881 and tea-producing regions across the Mainland followed suit during this period. In 1876, Yu Ganchen, a merchant from Anhui province, learned about British methods for producing red tea during his time in Guangzhou, gradually turning Qimen in Anhui into a red tea-producing region. 1874 was when so-called "Gongfu" red tea appeared in the village of Danyang in Fujian Province; it was also the year that Xing Village Souchong red tea appeared in Tongmuguan. Xiuning tea from Jiangxi Province is said to have been in production by 1823, eleven years before the "fully" oxidized, and now distinctly and truly "red" tea method of tea processing was developed by the British. As William Ukers notes in All About Tea, many new types of Gongfu red tea emerged in rapid succession at that time, indicating the refinement of old processing techniques and the appearance of new ones. Oolong comes from Fujian, green tea from Jiangxi, and some of these areas have effectively transformed into Gongfu-red-teaproducing regions that have continued for more than a hundred years, up to the present.

In the twentieth century, tea has become a global commodity. The makeup of the industry in tea-producing regions has stabilized, as the habits of consumers have also normalized. Red tea is particulary precise and stable in terms of quantity and quality. In the year 2000, the global output of tea was calculated to be 290 million tons, consisting of 70% red tea, 25% green tea and 5% other types. Red tea made its first appearance only a little over a century ago, and has since come to be enjoyed the world over for the simplicity involved in brewing it, its consistent quality and precise manufacturing specifications by mainstream standards. Green tea remains popular in specific areas, favored by the loyal tea-drinkers in non-minority ethnic communities. Both of these mainstream tea production methods have issues as well, often bringing teas to market at the expense of the environment. Oolong, on the other hand, is a delicacy among the minority groups of Fujian, Guangdong and Taiwan. Though it has some environmental and marketing issues as well, they are on a smaller scale. The mainstream tea market is less interested in oolong tea. The complicated brewing process, owing to the irregular quality of the leaves, has become an art form in itself. When we delve into tea, we find that it is all too easy to become enchanted by brewing tea gongfu, and exploring teas that require traditional skills to produce and brew.

In terms of its sensual qualities, red tea has a caramel aroma, a bright red tint and a flavor reminiscent of lychees or dragon-eye fruit, all of which encouraged tea lovers around the world to develop a taste for it very early on. From a factual perspective, the production, processing and distribution of the seven major kinds of tea differ in size and types of infrastructure, and there are even customs regarding the proper way to drink each of them. Moving into the highly inaccessible market of those who brew tea gongfu style, the usual method for consuming red tea, with its single-use brewing, has changed. Nowadays, people brew red tea like oolong tea, with gradually longer steeping times. I anticipate that, like puerh, red tea will come to be considered a high-end tea product. Red tea will join the ranks of other fine teas, worthy of brewing with skill and attention to detail. Hopefully, that will shift its production towards greater artistry and more attention to the environment as well!

We've been together before In a different incarnation And we loved each other then as well And we sat down in contemplation Many many many times you kissed mine eyes In Tír na nog