|

|

Emperor Huizong ruled from 1101 to 1125 CE. He has since come to be known as the "Tea Emperor." Not much of a ruler at all, the emperor spent most of his time composing poetry, painting, writing essays, holding incredibly grand parties and concerts, drinking wine and visiting his 3,912 ladies in waiting, including empresses, concubines, attendants and even courtesans he brought to the palace, shaming the sacred halls which had previously only ever had virgins enter its gates. Beyond that, he apparently took numerous trips into the city incognito, since apparently several thousand ladies weren't enough to satisfy him.

In his defense, the emperor was the eleventh prince and had not spent his early years preparing to become the monarch. He grew up expecting that the government would rest on one of his elder brother's shoulders. Though decadent, the emperor was also one of the most artistic, educated and charming men ever to sit on the Dragon Throne. He was a great patron of the arts, summoning poets, painters and musicians to him from all over the kingdom, making many of them famous beyond antiquity to the present, and establishing the Song court as an emblem of China's golden age of art. For most of the duration of his reign, his kingdom was at peace and its king free to seek the heights of less terrestrial peaks, though one may argue that Huizong would have been thus in any age. He himself was a gifted scholar, poet, calligrapher and painter, and several of his pieces are still exhibited in museums around the world.

Emperors of China took active roles in the production of tea beginning in the Tang Dynasty. Tribute teas were sent to the Dragon Throne from tea-growing regions throughout the Middle Kingdom, and at some periods of history spring was officially heralded when the emperor drank the first flush of spring tea. Though each emperor had the best of teas and no doubt enjoyed them, few were inspired as passionately as Huizong.

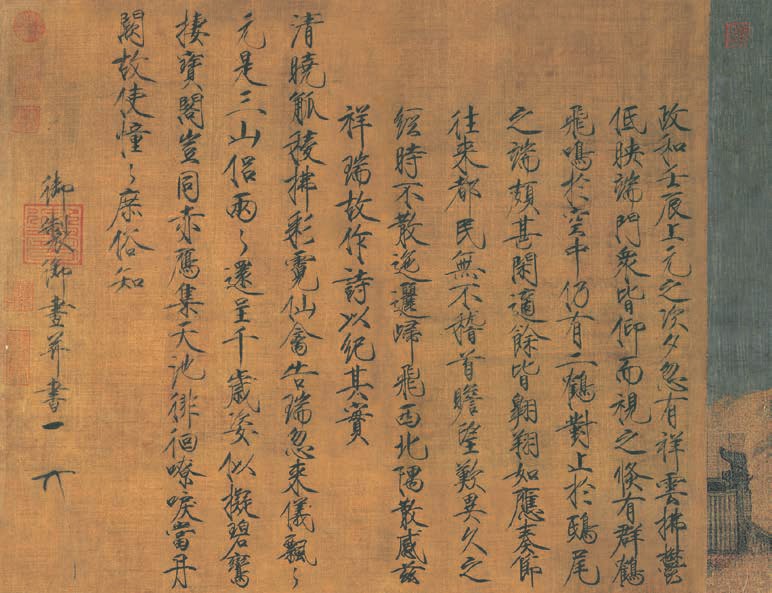

In 1107, the emperor composed his treatise on tea, entitled Da Kuan Cha Lun, which was a marvelous first in many ways. Very few "Sons of Heaven," as the emperors were called, brushed their own thoughts onto paper in this way; and the treatise contains thorough descriptions not only of tea preparation methods of the time, but also of the farming, harvesting and processing of tea into cakes, which all occurred very far from the isolated king in his palace. The emperor seems to have learned enough to start a farm and factory should he have chosen to. He was an amazing character indeed, and the fact that he found his way into the Story of the Leaf isn't so surprising, given his charisma and erudition, rarely shown by other emperors. One of the first English books on tea, The Chinese Art of Tea, by John Blofeld, has a lengthy chapter on the emperor in which the author describes his tea drinking and study of the Leaf so elegantly that I cannot help but quote him at some length:

Sometimes, when drinking tea alone in reflective mood, I like to fantasize about him. I am sure that somewhere within the depths of his magnificent palace there was a small, rather unpretentious room where the Lord of Ten Thousand Years experimented with fine teas, brewing them in various manners with his own august hands. No doubt such conduct was puzzling, and even shocking, to the horde of palace ladies and eunuch attendants whose duty it was to bathe and dress the emperor, wait upon him hand and foot and ensure that nothing remotely suggestive of manual labor - other than the wielding of a writing brush or Imperial chopsticks - ever came his way.

And indeed, no other emperor before or after is known to have prepared his own tea by hand. The introduction of his treatise also suggests that Blofeld was right in assuming that the emperor did understand the stillness inherent in tea, as he often states that tea is a time to set down the cares of the world, finding serenity away from daily life. It would seem that tea was a solace from the debauchery that marked other aspects of his life.

The emperor's kingdom fell into disarray as he more and more neglected it, and in 1125 a rebellion of the Northern Tartars stormed the palace and ended the Northern Song Dynasty. Huizong and his son were banished into exile beyond the Great Wall, where they would live in captivity for the rest of their lives. The emperor then wrote sorrowful poems, longing for the palace days that he had lived in his youth. His treatise on tea was studied by tea masters down through the ages, capturing all the art and spirit of tea art during his age.

Despite his lascivious tendencies, the emperor Huizong remains one of the most interesting and talented emperors ever to rule the Middle Kingdom. Like Blofeld, we may also perhaps envision him waking up before the attendants and servants even - perhaps moving the arm of some snoring ladies to do so - and quietly sneaking off to his private tea room to brew some morning tea away from all the hubbub of the palace. In that space, as his mind drifted softly into lucent peace, he was no longer an emperor, a king, a moral satyr, but a tea sage as simple and elegant as any mountain recluse. And in that same space we may join the emperor whenever we choose. We have raised many a bowl to him, as we all should. He was, after all, one of the first members of this Global Tea Hut!

We have a bountiful treasure trove of information to share, so that we can all steep in the life and times of the emperor. We have an amazing article, brushed by the erudite Steven D. Owyoung, which provides us with an in-depth introduction to the life and times of one of China's most charismatic and legendary figures. Michelle Huang, a renowned art historian, guides us through an exploration of the emperor's art. So let us don our nostalgic caps and explore the wisdom of teawayfarers long gone! There is a great peace in knowing that the bowl we drink from has been around so long, and that even the Son of Heaven, the emperor himself, is just a man sharing tea.

Our translation of the Treatise on Tea by emperor Huizong would not have been possible without the guidance and help of first and foremost Michelle Huang, and also Steven D. Owyoung, who provided edits, advice and added some poetry to the whisked broth we've made. Wu De also worked tirelessly and even without sleep to translate and annotate this issue, so let us also raise a bowl to him. Translating ancient Chinese is very difficult. Well-educated aristocrats like the emperor wrote with great poetry, implied meaning and quotation, as well as esoteric Daoist references. This translation is not meant to be definitive, but to add to the growing dialogue of tea wisdom in English.