|

|

When the imperial prince Zhao Ji ascended the Dragon Throne at age seventeen, he became sovereign of the wealthiest, most populous, and advanced state in the world. Known in history as Emperor Huizong, the eighth ruler of the Song Dynasty, he inherited an empire marked by stability, prosperity, and peace such that he once wrote a poem to pose a bold yet earnest query. Couched in verse and Daoist phrases, Huizong wondered if the eternal celestial records had not prophesied his good fortune, his rise and reign, for contrary to the rules of succession he was never highest in line nor designated heir apparent. Despite his surprise and apprehension at his elevation to emperor, Huizong wrote:

The Age of Sages embraces three thousand years, A time when Immortal Blossoms begin to bloom. Does the account in the Golden Register Foretell the coming of the Perfected?

"The Perfected" embodied the ancient notion of the sagacious and superior being, a person of high virtue and utmost attainment. The imperial conceit of the poet aside, Huizong was indeed a good and supremely accomplished man.

Born in 1082, Huizong spent his childhood amidst the luxurious palaces and gardens at Kaifeng, the Song imperial capital. He was tutored from a young age by eminent scholars and so received an excellent education based on the Confucian classics and their moral teachings. Entitled and enfeoffed the "Prince of Duan," he was the eleventh of fourteen sons sired by his father the emperor. With so many older brothers, Huizong was not expected to become ruler of the empire and thus devoted himself early on to the study of Daoist thought, the arts and culture. He moved at age thirteen from the family residence into his own palace, shepherded by a large personal staff of servants, officials and advisors. Free to pursue his keen interest in scholarly pastimes, he became erudite in poetry, highly skilled in music and brilliant in calligraphy and painting.

Huizong's fondness for the arts began within the Forbidden City, where the intimate residential apartments and the grand palace halls were beautifully decorated by generations of master painters commissioned to create majestic murals and fine scrolls. Designed by the empire's most famous architect, even his own palace of modest but princely rooms bore the works of noted artists. Walking from one hall to another, the young prince might happen on an artist adorning a wall, the painter busy but nonetheless willing to impart an impromptu lesson to a bright pupil. As emperor, Huizong organized painters into a palace academy and personally trained artists in the literary and technical aspects of the court style. A formidable painter in his own right, he specialized in a refined and minutely detailed verisimilitude of birds and flowers and figure painting. In keeping with scholarly tradition, Huizong learned to write well, not merely to communicate clearly and with erudition but to compose characters in a fine and elegant hand. He developed a distinctive manner of calligraphy known as Slender Gold, for his characters were sharply and precisely formed, displaying a brittle metallic quality as if the very script were cut from thin but precious plate. Huizong was an avid collector and connoisseur of antiquities, amassing collections of painting, bronzes, jades and ceramics that he displayed in palace galleries during meetings with his ministers. His interest in ancient bronzes spurred Song archaeology, the rediscovery and relevance of the distant past and the recasting of bronzes: the lost Nine Tripods, for example, which recalled the original empire of ancient times as well as represented the integrity of his modern Song state. His taste in ceramics favored celadons: the pale blue-green porcelaneous stonewares, the most famous and rarest of which were Ru wares created by the southern kilns and used by him as daily service within the palace. Huizong studied music and actively engaged the imperial music bureau, where he reformed ceremonial and ritual composition. He decreed the casting of bells, the writing of ritual composition, and the training of court musicians in the performance of the new music. For Huizong, rectitude and harmony of sacral song exemplified his reign and enriched his imperium through tonal and cosmic accord with Heaven. His reforms were met with reports of auspicious signs in which cranes, those ancient symbols of immortality, gathered to soar en masse above the temples and shrines of the palace.

As for musical instruments, Huizong was personally enamored with the hushed dulcet tones of the silkstrung zither, and he performed the instrument as a gifted musician. Unlike grand orchestral music, the sound of the zither was small, soft and muted - its tone and tenor best suited to close chambers and intimate gatherings. The musical score known as the Tablature of the Inner Chamber preserved the notation devoted to the fingering techniques of the zither - ascending and descending glides, strumming runs and bell-like plucking - that characterized the court compositions of Huizong. Like the man himself, the music was described as "elegant and fascinating."

Huizong was a master of literary allusion, wielding his brush not merely towards pictorial realism but also to evoke music, tea, and other forms of art. For example, the handscroll Court Ladies Preparing Newly Woven Silk was ascribed to him as a pictorial metaphor of the old zither melody Pounding Cloth. The scroll Listening to the Zither, also attributed to him, was thought to depict Huizong playing out of doors for his ministers, one of whom adorned the painting with a poem. The minister described the burning of incense and a moment of transcendence heralded by the wind:

...A zephyr seems to enter the pine, songfeng. Looking up to see dear friends, Like hearing the song of a string-less zither.

Meaning to please his sovereign, the poet deftly employed the literary phrase wind in the pines to wonderful effect, for songfeng was a metaphor for both zither and tea, two of Huizong's favorite pursuits and realms of expertise. Dating from the sixth century, the poetic phrase songfeng, "wind in the pines," was a scholarly motif that conjured in the mind's ear the soft soughing of pine needles brushed by a gentle breeze. Among the literati, hearing the wind in the pines was a solitary thing, a moment of reflection that rose with the whispery sound and slowly died away to silence. Fleeting yet resonant, the sigh of the wind was likened to the muted vibrations of the zither strung with soft silk. A Tang dynasty poem captured the ephemeral essence of songfeng: "The wind in the pines fades like the sound of the zither..." In time, wind in the pines became a metaphor for the song and sound of the zither.

Songfeng was also an allusion to the art of tea. Wind in the pines was likened to the sound of the kettle and to the skill of boiling fine spring water: thoroughly heating the liquid while still preserving its fresh and lively character. The Tang tea master Lu Yu described the practice in the Book of Tea:

Of boiling water, when bubbles appear like fish eyes and there is a faint sound, that is the first boil. When bubbles climb the sides of the cauldron like strung pearls in a gushing spring, that is the second boil. When appearing like mounting and swelling waves, that is the third and last boil. Boiled any more, and the water is old and spent and undrinkable indeed.

In the late Tang, however, water was no longer boiled in an open cauldron but rather heated in a closed ewer, the boiling water unseen and its bubbles unobservable. To determine the proper boil in such a kettle, tea masters listened instead to its sounds. A later poet described the moment:

Wind in the pines, rain in the junipers: When the sounds first arrive, Quickly take the bronze kettle from the bamboo stove. Await the sounds in silence, and then The cup of Spring Snow tea surpasses ambrosia.

Thus, attending the fire and waiting for wind in the pines was a meditation, a moment of stillness and reflection until songfeng - its murmur and pulse - signaled the instant when water reached the perfect point for brewing fine tea.

Tea and zither were linked in the literary mind by the qualities they shared. In the mid Tang, the poem entitled Zither and Tea related instrument and drink by comparing the zither's most ancient song with tea's most ancient source: "Of tunes, the zither knows only old Green Water; of tea, the herb's most ageless leaf is only Mengshan." As a musical instrument of subtlety and restraint, the zither accorded with qualities akin to tea.

In the Tang Book of Tea, Lu Yu described the true nature of the herb:

Tea is innately reserved and temperate. Expansiveness is inappropriate to tea. Thus, its taste is subtle and bland. Even in a full bowl, when half consumed, its flavor is elusive. So, how can the nature of tea be described as expansive? The color of tea is pale yellow. Its lingering fragrance is exceedingly beautiful.

The merits inherent in the faint color, bland taste and enduring aroma of tea were also intrinsic features of the zither; its soft, abiding tones long considered "refined... uncomplicated... insipid."

With his talent for picturing poetry, Huizong combined tea and zither in the painting Literary Gathering (shown on pg. 32). Like the painting Listening to the Zither, the activity was set in the open amidst the trees of the palace gardens: a group of men surround a large table arrayed with food and wine, while in the foreground servants prepare tea; the zither rests for the time being on a large stone slab under the pendent willow. Despite the convivial scene, the mood of the painting is oddly expectant. The tea has yet to be savored, and the zither yet to be enjoyed. It is a timeless moment of pure anticipation for the twin pleasures of songfeng, wind in the pines.

Huizong and his art of tea were indebted to generations of Song emperors and the precedents set during their various reigns. The story of Song tea began in 977, when Emperor Taizong received tribute tea from Fujian, a place many hundreds of miles from the imperial capital and far to the south. The large rounds were named Dragon Tea and bore the images of mythic serpents and fabulous phoenixes. Grown in the warmth of the subtropical zone, the quality of Fujian leaf was superior to tea produced in the declining imperial gardens at Changxing in Zhejiang, a region once graced by a moderate clime but since turned cold, frigid enough to destroy plants and freeze Lake Tai. Taizong favored Fujian and decreed the establishment of an imperial estate below Phoenix Mountain at North Park, a collective of small tea gardens with descriptive names like "Chicken Bush Hollow," "Roaming Ape Ridge" and "Flying Squirrel Nest." In 996, nearly twenty years later, Taizong received a tea called Stone Milk, a small cake of leaves that brewed to a pale hue, a light calcium color reminiscent of stalactites dripping from the ceilings of deep caves.

Successive emperors benefited from Taizong's foresight, receiving yearly tribute tea from Fujian in the form of rounds, squares and wafers with names such as "Dragon in Dense Clouds," "Soaring Dragon Auspicious Clouds," and "Dragon in Hidden Clouds," all names that flattered each ruler, his sovereignty, and the prosperity of his reign. The tea reached the capital in elaborate packages by special courier:

In the first ten days of mid Spring, the Transport Bureau of Fujian sends as tribute the first fine tea which is named "New Tea for Examination from North Park." All of the tea is in the shape of squares in small measures. The imperial household is offered only one hundred measures; they are kept in soft pouches of yellow silk gauze, wrapped in broad green bamboo leaves, and then again in linings of yellow silk gauze. The tea, which is sealed in vermillion by officials, is enclosed by a red lacquered casket with a gilt lock. It is further kept in a satchel woven of fine bamboo and silk, and thus protected by these many means.

Once in the safety of the palace storerooms, the tea was carefully divided into portions that were sent to the imperial ancestral shrines as sacrifice and to select members of the aristocracy:

The tea is made with the tenderest leaf buds whose shapes resemble bird tongues. One measure of tea requires four hundred thousand leaves. Yet, this is barely enough to make a few bowls to sip. Sometimes, one or two measures are given to the outer imperial residences, the distribution determined by family lineage. The dispersal of these gifts is a courtesy and considered a wonderful present.

The largest share of tribute was held in reserve for the emperor who sent personal gifts of the tea to the empress, the high consorts and a select few of the great ministers. Rare and unavailable to all but the emperor, the tea was nearly priceless. Estimates placed the value of a single measure of tribute tea at forty thousand in silver. Such was the aura of power surrounding the dragon rounds that it was once said that the flowers of spring did not dare open until the emperor had drunk the first tea of the season.

Not content to merely possess the finest tea, Emperor Renzong once commissioned a report on the tea practices of Fujian so as to better appreciate the making and drinking of the precious dragon rounds from North Park. The official charged to provide the account was Cai Xiang, a scholar from Fujian and the greatest calligrapher of his generation.

In 1045, Cai Xiang was appointed special administrator to Fujian and within two years came to oversee the province's Transport Bureau as well as the annual tribute of its tea. On the presentation to the emperor of his book Record of Tea circa 1050, Cai was credited for advancing the manufacture of dragon rounds and for providing the first explanation of the process. He further offered Emperor Renzong insight into the aesthetics, utensils and techniques particular to Fujian as well as the preparation, service and drinking of tea in the Fujian manner. At the time, some tea was formed into rounds and other shapes, dried over a low fire, and then glazed with an expensive aromatic, such as musk or "dragon brain," a peppery camphor imported from Borneo. Cai famously noted in his record of Fujian tea that "among the people of Jian'an who practice tea, none add aromatics lest they take away from tea's true fragrance." Cai Xiang and his account were followed by several other authors whose writings described in detail various aspects of Song tea, especially that of North Park, its facilities, gardens, products and leaf characteristics.

During the Daguan or "Reign of Great Vision (1107-1110)," Emperor Huizong wrote the Treatise on Tea. The tract was a remarkable display of his knowledge of the plant, its cultivation, harvesting, and the manufacture of the leaf into dried cakes. The treatise further revealed that he was also a discerning connoisseur and an accomplished master of the art of tea.

It is interesting to note that during his adolescence, Huizong was tutored by three teachers, two of whom were from Fujian and who indubitably instructed the prince in the art and etiquette of tea as an important part of his social if not his cultural education. His household staff of eunuchs, managers and mentors assisted Huizong in building a library, acquiring a collection and loans of rare books on the subject of tea. With an increasing imperial stipend as he grew older, the prince easily afforded quality teas from the private estates, the fine ceramics used in the drinking of the leaf, and the special equipage used in the preparation of tea for competition. Perhaps as a result of his growing expertise in tea, he was indulged by the emperor and allowed to raid the imperial stores for rare tribute teas, provided of course that from time to time he served the spoils of his forays to his father and empress mother.

During his reign, Huizong introduced white tea, proclaiming its inaugural manufacture at North Park. Everything about white tea was superior. As a plant, it was rarer than rare and singular in form. White tea was wild, a truism of all great teas in Daoist legend: its leaves were "nearly translucent" like the pale wizened immortals who prized tea more than jade or cinnabar. Fine textured and sublime, a cake of white tea "glowed" like a precious gem. Huizong continued to favor white tea above all others. In 1120, some ten years later, the emperor received a newly created tribute tea named "Dragon Rounds More Beautiful than Snow." The tea was a variation of a white cake known as "Silver White Threads on Icy Bud" but made without aromatics and distinguished by "small dragons undulating over the surface."

Tea in the Song shared in the historic pursuit of foam, the fine bubbles of liquid and lather that had long defined the art of tea. In the third century, the Ode to Tea first claimed tea foam as the ultimate quest:

Serve tea with a gourd ladle, emulating Duke Liu. Only then can one begin to perfect thin froth splendidly afloat, glistening like drifting snow, resplendent like the flowering of spring, Chaste and true like the color of autumn frost...

In the Book of Tea of 780, the Tang master Lu Yu wrote of froth:

Froth is the floreate essence of the brew. Froth that is thin is called mo; thick froth is called po; that which is fine and light is called flower, hua. Flower froth resembles date blossoms floating lightly upon a circular jade pool or green blooming duckweed whirling along the winding bank of a deep pond or layered clouds floating in a fine, clear sky. Thin froth resembles moss floating in tidal sands or chrysanthemum flowers fallen into an ancient ritual bronze. For thick froth, use the dregs of the tea remaining in the cauldron and heat it. Reaching a boil, the thickened floreate essence of the brew then gathers as froth, white on white like piling snow. The Ode to Tea described it as "lustrous like mounding snow" and "splendid like the spring florescence."

Inspired by images of frost and snow, Huizong sought lighter and lighter teas. The finest caked tea was "luminescent and white." The finest liquid tea whisked to a "stiff" meringue. Huizong succeeded in fulfilling the ideal with his decree, prompting the production of white tea at North Park and introducing its special properties at court. He doubtless astounded his competitors, winning all the tea contests by whisking up the whitest and thickest froth. One courtier recalled an incident when, overwhelmed by enthusiasm, Huizong accidently splashed tea foam into his own face.

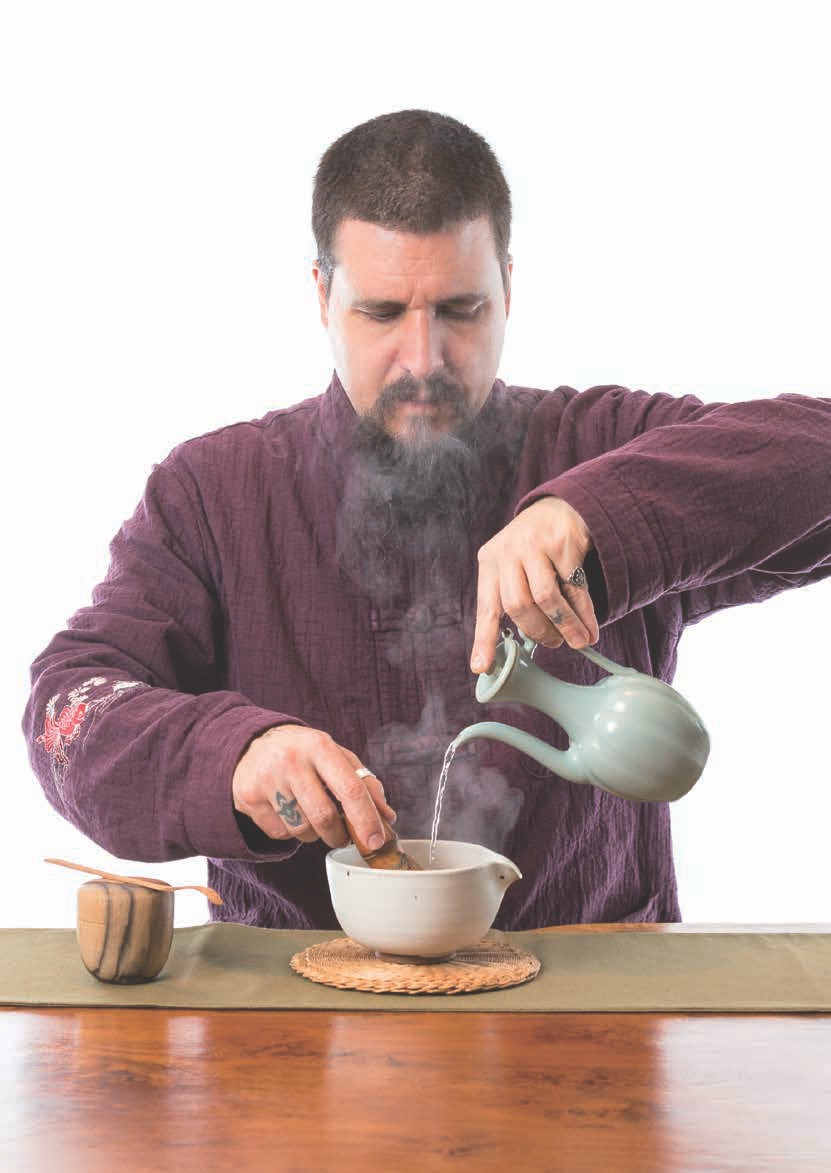

In the Treatise on Tea, the form of things followed the function required. Design enhanced precision and increased economy of movement. The spout of the water ewer poured a forceful but controlled stream from a tip that was so meticulously crafted as to be utterly dripless; its use free of extraneous drops that might ruin an otherwise elegant service. Color, size and proportion mattered. The bowl accommodated the tea: too large and the color of tea was diminished; too small and whisking was impeded - the tea lacking smoothness and froth. Proper tools and discipline were everything, and technique translated naturally from medium to medium. The tea whisk was weighted and balanced, its sword-sharp tines whipping up bubbles and foam - "millet and crab eyes" - to paint the bowl; the handle was held "loosely yet firmly" like a writing brush deftly wielded by the supple wrist of a calligrapher. Distinctions between the arts at times simply disappeared.

Huizong seems to have enjoyed sharing tea with his family and ministers. Not only did he serve them with his own hands, but he was also generous and gave away cakes of palace tea as presents. He once wrote a poem on the event of receiving a tribute tea from North Park:

This year, Min altered the tribute tea. All the spring buds were devoted to creating Soaring Dragon of Ten Thousand Years. On opening the imperial chest, a fresh scent filled the air. I bestowed the tea upon high ministers and officials.

In another poem, Huizong returned in the evening from a spring outing, a day of playing seesaw and drawing in the fragrance of orchids. Tired and spent, he rested in the hall listening to the sound of grinding tea.

As a poet of tea, Huizong was often very specific, allowing the season, place and purpose to override lofty lyricism:

In the first month of spring, the finest Jianxi buds are chosen. I take the tea to the library window for a critical look But the place is not suited for judging its quality, So I hold the bowl closely to examine the snowy bloom.

Of the many poems Huizong wrote in his lifetime, only four hundred fifty or so remain.

At age forty, Huizong was at the height of his aesthetic powers. Indeed, his contributions to culture and the art of tea were hallmarks of his reign and remained artistic high points for centuries thereafter. Yet, all his cultural sophistication and artistic attainments could not spare him from a dire and terrible destiny. Unlike the purity of his snowy white tea, and at odds with his optimistic "Reign of Great Vision," Huizong's future was dark and dirty. Threatened on its northern borders, the Song had for decades negotiated an uneasy peace with the tribal Liao of the Asian steppes. Then in 1121, Huizong was tempted by the Jurchen of Manchuria to attack the Liao. Under the joint armies of the Song and Jurchen, the Liao were defeated. In 1126, however, the Jurchen betrayed Huizong and declared war on the Song, sending an invasion force to within sight of Kaifeng. Huizong abdicated the Dragon Throne to his son and fled south, only to be captured and deported north to Manchuria. Nine years later, abused and broken, Huizong died in captivity at the age of fifty-two.