|

|

Huizong (徽 宗) (1082-1135) was one of the most important emperors of the Song Dynasty. All Chinese students learn about and memorize many aspects of his life in middle school history classes. Unfortunately, the wellknow facts about Huizong's life are not really trustworthy, often lapsing into legend and folklore. When the court was attacked by the "Barbarians from the North (Jurchen)," Huizong abdicated his throne in hopes that his son would know how to deal with the war, as he surely could not. The renegade court retreated to Hangzhou, along the Yangzi River. Unfortunately, eight short months later, both Huizong and his son were captured by the Jurchens. Their lives were spared, but both were conferred extremely derogatory titles, deprived of their nobility and had to perform humiliating ceremonies to honor the Jurchens in public.

As Confucianism spread across the realm, later generations would attribute this disaster to Huizong's overwhelming affection for the arts. There may be some truth to this. He was a soft ruler. Besides being a great connoisseur of all art forms, he was also a fantastic calligrapher and brilliant painter himself. Scholars have often portrayed Huizong as an intellectual who enjoyed all the high arts, such as playing the zither (guqin), as he does in the famous painting (pg. 20), rather than as the emperor he was. Huizong invited all the best painters to court and had them compile three compendia of his huge collection of calligraphy, paintings and other antiquities. Regardless of his political performance, Huizong made a huge contribution to Chinese art by elevating the social status of painters and documenting the artistic milieu in and around the twelfth Century of China. And that is reason enough to celebrate his legend as much as his person.

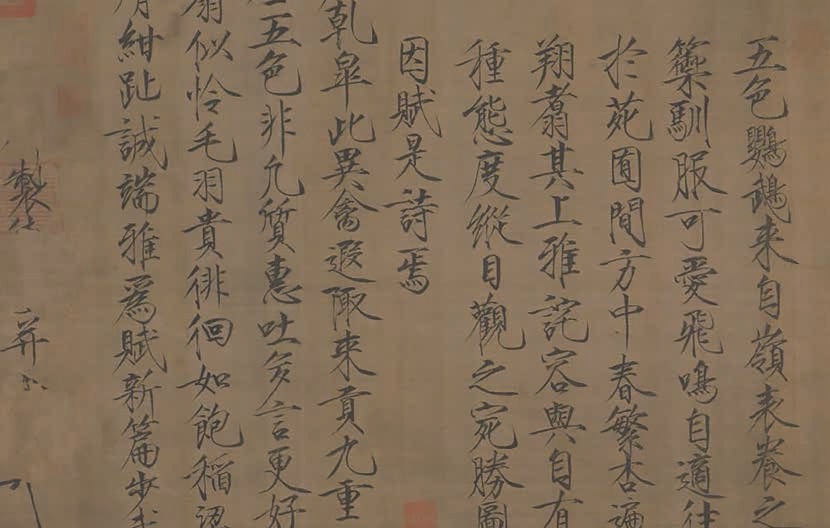

For most Chinese, there are two lasting impressions of Huizong: his loss to the "barbarians" and his oneof-a-kind calligraphy style. Chinese calligraphy had been highly developed since its arguable peak in the fourth century. From then until Huizong, we do not find much innovation in styles. In general, the Chinese aesthetic values a balanced composition of well-rounded and uniform brushstrokes. However, Huizong's idiosyncratic Slender Gold style (瘦金體) has been called by critics "peculiar," "bizarre," "unbalanced" and even "crooked," which somehow also reflects his irresponsible personality and nonconformist attitude. However, if one can strip away what scholars, past or present, suppose to be "good quality," then one can appreciate the uniqueness of his brushstrokes, not to mention the spirit and glory of his art. Furthermore, when all the brushstrokes are evenly placed, and in perfect order, then, one could argue, that all the characters look and feel two-dimensional, like they are in print. However, the seemingly uneven, chaotic and fluid strokes of the Slender Gold style, varying in size and direction, create a sense of three-dimensionality. The "broken" frayed ends of the emperor's strokes suggest velocity and swiftness.

By manipulating the brush and ink, Huizong quite masterfully bestowed his calligraphy with a sense of otherworldly three-dimensionality! In Western art, most movements trended and strove towards such three-dimensional realism, called "trompe l'oeil" in French. This wasn't a value in Chinese art, which makes Huizong's calligraphy all the more special. There are no shadows or perspective to give the illusion of three-dimensionality in calligraphy, yet he somehow achieved just that.

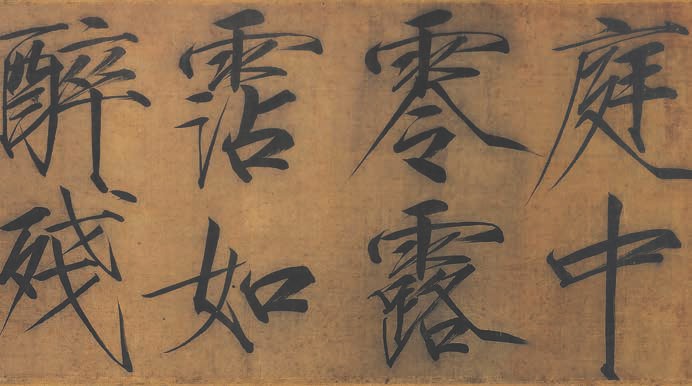

When we focus on the detail of the upper right part of the top left character, we see several white, hairy ends like the first gray starting to silver a wiser man's beard. If you yourself were trying to achieve this effect, you might try using less pigment, so that the end of a long stroke would run out of paint, leaving the ends of the stroke uneven. It is more likely that the emperor created the same effect by brushing a long stroke with lots of pigment moving across the paper at a high velocity, which is, of course, much more difficult. Brushstrokes with jagged, rough ends are termed "flying white (飛白)" in Chinese. Such speed makes mastery a lofty goal, and also fills calligraphy with Daoist sentiments. In appreciating Huizong's calligraphy, one might imagine his stance and movements, his grace and speed. If you look with your heart, you can see this movement in the characters, not unlike how we can see the force in Jackson Pollock's paintings. (He is actually the perfect Western analogy, since many critics also disapproved of his "messy" style.) In this way, Huizong was instrumental in the transformation of Chinese writing into pure art. He not only created a unique style with texture and depth, but also, like all true artists, he challenged mainstream aesthetics, which were based on the supremacy of well-rounded strokes and perfectly balanced composition. By brushing ink with such virtuosity, Huizong conjures up spirit, movement and three-dimensionality. We feel the Daoist leanings in his work, and the viewing brings as much movement as the painting did. Huizong's calligraphy dances off the page, carrying us with it. His work is truly Heavenly; his strokes carry us skywards, with the cranes he loved to paint.

Huizong experimented in mixing different media in his paintings. The painting below shows a parakeet in vibrant color perched amongst plum blossoms. In order to portray the pitch-black eyes of the parakeet faithfully, Huizong dotted the eyes with a thick blob of lacquer. This is the first recorded use of lacquer in the history of Chinese art.

Even though he favored poetic representations in the painters' exams that artists had to take to enter court, he considered accuracy a prerequisite of a good painting. Therefore, his official portrait should be a fairly accurate resemblance. (Your gift of the month!)

A painting that exemplifies his passion for and attention to detail is Literary Gathering, which also depicts tea drinking. Even before Huizong there had been numerous famous paintings of officials gathering together to compose poetry while drinking wine. In Huizong's time, tea was often offered at the end of such parties to "wake people up" from the effects of liquor and ease them into physical activities such as dancing afterward.

In his version, Huizong painstakingly documented all the paraphernalia for making tea and the lavish array of snacks at such parties. There are a total of 122 ceramics on the big table and 21 pieces of teaware on the three smaller tables where the servants are depicted preparing tea. On the big table (shown on the next page), where the gentlemen are sitting together conversing, each has his own set of teaware, a wine cup that is elevated by a small dish, a small bowl, and three small dishes for different snacks or for food waste. In addition, on the central part of the table, there are smaller dishes with snacks, different fruits and even bonsai, as well as other decorative plants - all elevated on bigger plates. The tall vases inside the big bowls on both sides of the table are wine vessels. At that time, people preferred wine that was warmed higher than body temperature. The bowls contained hot water to keep the wine warm.

In the service area, the servant standing in the middle is scooping whisked tea into smaller bowls placed on top of black lacquer dishes to be served. On both sides of that servant, the vases on the tables contain hot water for whisking tea. The servant on the right, who is mopping the table, might be the one who's just finished whisking and is, we might imagine, getting ready to prepare some more. In front of the serving tables on the ground, there are two stoves for boiling hot water and a small chest to store all the smaller paraphernalia for making tea. However, judging from the fact that some officials have already left their seats and the bamboo whisk is missing from the table, this may be the end of the feast, and the entertainment will soon begin. The vision of such tea is a treat for a modern Chajin, especially over a bowl of this month's white tea!

Another painting that ties Huizong's love of the high arts to tea is this one entitled "Auspicious Cranes" (pp. 17-18). As a romantic emperor, he was obsessed with all kinds of auspicious signs that were testament to his "Mandate from Heaven." He was especially fond of pure white and/or extraordinarily unique natural objects. This may also play a part in why he strongly favored white tea, since other tea connoisseurs of the time were not as impressed. Huizong recorded an incident when a flock of white cranes hovered above his palace, stark against the fantastic clouds, for a long period of time. Many civilians nearby saw this rare event and came out to appreciate the wonderful omen. The Chinese consider the crane a lofty animal, especially the Daoists. A crane can only survive in a clean environment; hence it is a sign of purity and a lofty abode. Also, they balance large bodies on small legs effortlessly, often standing on a single leg for hours. They also stand still for extraordinary lengths of time, appearing to be asleep, when in fact they are very aware, waiting to pounce on a fish with great concentration and alacrity. Huizong also composed a poem to celebrate the omen of the cranes, which to him signified a benevolent ruler and a peaceful and prosperous world. Ironically, many would argue that his reign was not auspicious at all, ending as it did.

Huizong not only enjoyed painting, he also spent a lot of time and energy promoting painters and appointing them as court officials. He changed the title of the court painters' guild to the "Hanlin Painting Bureau," which was the same name as a prestigious official bureau that had been set up in the previous dynasty. From the eighth century, those who wanted to pursue a court appointment had to attend the same exams, from annual county-wide and provincial exams to the national exams held but once every three years. Just as literati were judged on the essays they wrote on topics such as the characteristics of a good governor, painters in Huizong's reign would compete based on their ability to use imagery to represent the lyrical essence of a given poem, rather than merely to depict objects realistically. For example, the verse "an ancient temple tugged at the mountain" was best represented when a painter refrained from showing any indication of a temple structure, only painting a monk fetching water on a mountain. In the same vein, the awarded painting that captured the verse "Returning home, trampling on flowers, the hooves of the horse smell great" did not portray any flowers at all, just butterflies dancing around the hooves of a horse. Court painters were either literate painters with advanced painting skills or good poets who could do more than illustrate words. Such artists were eventually promoted to officials of China during Huizong's reign.

Huizong was the best of artists, and yet the worst of emperors. He had everything at his disposal in the vast palace, yet ended his life without a possession. You could say that in quite mythic terms, he sacrificed the palace for art, Earth for Heaven. He suffered for his art, as some say all true artists must. If he had not been emperor, he might not have had the luxury to experiment with innovative calligraphy styles, paint such glory, or, as he himself says in his treatise, had the "leisure" to write about tea. Nor could he have amassed such a huge collection of art, changing the history of art in China forever. Though it may be trite to make light of his suffering from such a distance in years, it seems almost in harmony with the poetry of his legend that his focus on art has made him infamous as one of the worst emperors. It seems almost scripted that he faced two terrible years of imprisonment, five long years of exile and died without a proper burial, alone beyond the northern frontier. From the glory of Heaven, the true artist knows the agony of Earth that must always live intertwined with the ecstasy. And Huizong was a true artist and Chajin.