|

|

'Tis insightful that plants grow in the opposite direction to human beings, with their roots as their heads underground, they grow from the bottom up into our world...1 Amongst all the many resources befitting human beings, we find only necessities and luxuries. Common people and children alike know of the need for necessities such as rice and millet, and the hunger that demands food, as well as how essential silk and hemp are to protect us from the weather. However, such as they are not always able to appreciate the way a fine tea distills the exquisite essence of Ou and Min,2 endowed with the spirit of those hills and streams. A fine tea can dispel and cleanse obstructions, leading to clarity and balance. But the seemingly subdued flavor, and the delicate tranquility inspired by fine tea is an acquired taste that can't be enjoyed in a time of upheaval.3

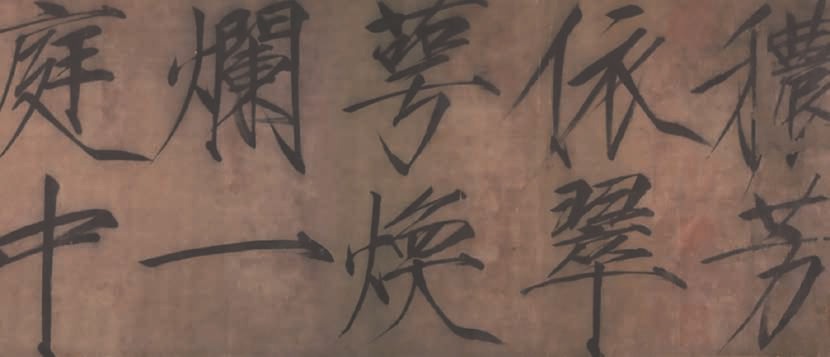

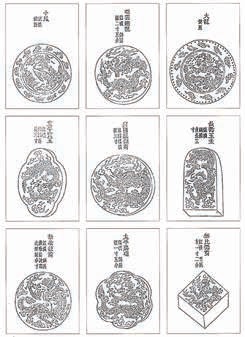

Since the early period of this dynasty, the tea cakes marked with dragon and phoenix patterns called Longtuan,4 Fengbing5 and Huoyuan6 from the Jian River area have been made exclusively for the imperial family.7 These treasured cakes have become the most famous teas under Heaven. Nowadays, hundreds of lost crafts and arts are flourishing again due to the effortless currents8 of the four seas.9 Court officials and civilians alike work so hard and well that the emperor does not have to expend much effort governing. As a result of this peace and prosperity, the gentry and peasantry have both benefitted from the glory of the imperial court, and become cultivated in high culture, refining activities such as tea drinking. Consequently, tea has flourished over the past decade. Tea farmers have learned to pick only the finest of leaves, have improved their processing skills, cultivated more varieties of tea than ever before and the people have developed new brewing techniques to prepare them. You could say that there is always a natural rise and fall to any cultural practice, and the market surrounding it, but destiny, and the Mandate of Heaven, have also played a part in the rise of tea culture. For during times of turmoil, one has to strive that much more in the search for daily necessities that one hasn't the free time to devote to a luxury like tea.10 But after a long period of peace, one begins to grow bored with the usual routine and pursue luxurious and exquisite novelties. For example, people nowadays are spending more and more time indulging themselves in grinding tea cakes that are as precious as jade or gold in order to savor the tea's essence that much more.11 All the nobles under Heaven can afford to revel in the appreciation of exquisite rare tea, seeking its literary gems and prettysounding bits of golden verse, sipping from its flowers and sucking on its blossoms, weighing the value of its literature, debating the distinctions in its appraisal and judgment, not to mention the innovative designs of their teaware collections. Even the poorest folk are not ashamed to store some tea at home.12 Verily, in such an enlightened era, a person can choose to express themselves to the utmost degree, and even the spirits of all the cultivated plants can be developed to their fullest potential.13 I too happened to have a day of leisure to dwell upon the subtleties and wonders of tea. And for the posterity of later generations, I would like to share my experience in twenty small essays to be called the Treatise on Tea.

Note on Title: The original title is "Treatise on Tea (茶論)," but it was later shortened to "On Tea." We suppose that the shortening was to avoid confusion with essays on tea written by others. For example, Shen Gua, (沈括, 1031-1095), a famous critic from Hangzhou, in a slightly earlier time also wrote an essay entitled "On Tea." Out of the twenty-six years he reigned, Huizong (1082-1135) changed his regnal title five times. As a result, Huizong has six regnal titles altogether. Chinese literati liked to impress others by name dropping, or being very precise in minor details. Since this treatise is written during the Daguan reign period, which literally translates to "Grand View", people have also referred to this treatise as the "Daguan Tea Treatise."

When planting a tea garden along a steep slope, it is better to cultivate the eastern, sunny side. On the other hand, if the garden is located on a hill or in a valley, then it is better to choose a shady area. According to traditional Chinese medicine, the nature of mountains and rocks is cool, and therefore not conducive to the vibrancy of plants, which can affect the essence of the tea. It is important for craggy, rocky gardens to get enough sunshine and warmth for the trees to grow well.1 In general, there is plenty of sunshine on gentler slopes and the soil is often more fertile in the valleys. The trees there tend to flourish, budding in verdant flushes, though they often wilt and fall more readily. Such tea tends to be more aromatic and richer in flavor. It is important to ensure that there is enough moisture flowing through the hills and valleys to strengthen the leaves and harmonize the balance of the garden. Only when the yin and yang of the natural environment are well balanced will the tea grow vibrantly.

The labor of crafting tea begins at the Awakening of Insects,2 though the harvest will depend completely upon the weather. If it remains cool at this time of year, the buds unfold slowly. The farmers will then have enough time to work calmly, and the color and flavor of the tea will be harmoniously balanced. However, as it gets warmer, the buds grow rapidly and the farmers must hasten to the pace of the leaves. It is a heavy burden for them to force their labor around the sundial in order to finish the tea processing.3 After the leaves are plucked, they are steamed.4 Then the leaves are pressed to remove excess moisture and bring out the essence from within.5 After that, the leaves will be ground and compressed into the final shape of the cake.6 Timing is everything in the creation of fine tea. With any hesitation, the color and flavor of the tea will be off balance. Therefore, tea makers celebrate the blessings of Heaven when the weather cooperates with the harvest.

Tea leaves can only be picked in the brief moments between dawn and the rise of the sun. The pickers should pluck the young stems off with their fingernails, without touching the leaves at all, for fear that the energy, smell7 and sweat from their fingers could overpower the delicate leaves. They often bring fresh water with them to dip the buds in after plucking them. The buds that are the size of a grain and resemble a sparrow's tongue are the highest grade. One stem and one leaf are choice buds, followed by one stem and two leaves. The rest of the flush will be inferior. When the young buds first emerge, plucking such nascent white, bulb-shaped leaves would cause the tea to be off balance and bitter. And it is too late if the leaves have withered, looking like the dark knots of a bird's tawny band,8 tarnishing the color of the tea.9

Steaming and pressing the leaves are the most crucial steps in the whole process of making fine tea. If the leaves are under-steamed, they will be weak and pasty. The color of such tea is green and the liquor tastes bitter. And if the leaves are over-steamed, the buds shall wilt. The shade of such a tea is reddish, and the compressed cakes crumble apart too easily. After steaming, pressure is applied to draw out the excess moisture infused during the blanching process. If the leaves are pressed too firmly, the aroma and flavor of the tea will escape. On the other hand, if the leaves are not pressed enough, the liquor will be dark and taste tart.10 When the buds are steamed to perfection, the tea will fill the room with a wonderful fragrance. Knowing when the moisture has been pressed out and the essence released, and lifting pressure at that precise moment, requires great skill. In fine tea, three-fourths of the quality lies in mastering these two steps.

Washing the buds as they are picked, to maintain purity, is of the utmost importance. In the same way, the utensils used in tea processing must also be clean and pure.11 The leaves have to then be steamed to the perfect degree, completely ripe for grinding, and then roasted to a flawless balance. If the tea liquor is gritty, then this point of perfect poise was not achieved. If the marble of the leaves in the finished cakes looks red and dry, then this batch of tea was over-roasted. Consequently, before the whole process starts, tea makers should master the art of harmonizing their work with Nature, so that the sun rises and sets with the production of a perfect tea, from harvest to completion. The key is to ensure that there is enough daylight and skill to finish processing all the harvested leaves in one day, as any leaves left undone at sunset shall be robbed of their quality by the passage of night.

Tea cakes are compressed into many shapes and sizes, similar in kind, though every one is unique, not unlike people's features. When the leaves are compressed too tightly, the cake will be dry. There will then be crevices on the surface of such tea cakes. Cakes that are too loose, on the other hand, are full of moisture. They feel harder to the touch, and display shallow wrinkles across the surface. Tea cakes made within a single day shine a bluish-purple hue, whilst those that are allowed to pass overnight halfway-done are matte, obstructing the light.1 Some cakes might seem shiny at first glance, almost glossy, like a red prayer candle, though the ground powder turns white and the liquor is yellow. Other cakes are tightly-pressed and pale green, with a grayish powder that looks even bleaker after water is added. Some cakes are shiny in appearance, and hence popular to beginners; though, as they later discover, the inside is dull. Conversely, there are tea cakes that are bright and silvery on the inside, even though the surface does not reveal any of the hidden virtue inside.2 The vast spectrum of tea cakes makes it difficult to make lasting generalizations. However, the qualities of the finest tea cakes can be summarized as follows: A fine cake should be illuminant in a single, bright and clear hue, the texture should be congruent throughout, and the cake should be neither too loose nor too tight. A tea cake should not crumble easily; there's a certain delightful resistance when grinding a fine cake.3 Some aspects of a fine tea can be expressed in a rule of thumb, but to truly comprehend quality requires experience, insight and intuition.4 Unfortunately, some greedy merchants purchase tea that has been steamed by private tea producers to save time in their own processing.5 Others crush tea cakes and re-shape them into their own molds. Even though they can claim such re-processed cakes as their own, and the appearance and the label might be similar, one can learn to discern their true quality by scrutinizing the color and texture of the cake carefully.6

White tea is unique amongst all the tea under Heaven. The branches of the trees flare out wide and the leaves are so thin they are nigh translucent. White tea trees grow wild and sporadic, so they cannot be domesticated by man. White tea cakes are only available from four or five houses,7 which own but one or two trees respectively. Therefore, each house can barely produce up to three cakes. These priceless cakes are different from all others, in name and shape alike. Instead of the usual square-shaped cake, called a "pian," white tea is made into a floral-shaped cake called a "kua." The precious rarity of white buds, and therefore lack of experience processing them, means that it is difficult for tea makers to perfect the art of crafting white tea cakes. And if these treasured white leaves are not processed with great care and skill, they lose their matchless distinction and fall into mediocrity. The top grade white tea cakes have a harmonious texture and appearance inside and out. Such cakes glow, radiant like the finest jade held up to the light. Some private tea manufacturers manage to produce white tea cakes, but the quality is inferior.8

The best grinders are forged of pure silver. Wrought iron produces the second best, and pig iron is the next highest. Since pig iron does not go through a thorough smelting process, there are a lot of impurities in it, which can contaminate the tea.9 To say the least, the color of the tea powder will be darker using such a grinder. The sides of the pestle should be sheer and the trench deep. The rolling grinder on top should be sharp and thin. When the groove is deep enough, the ground tea powder concentrates in the center and is easier to collect. And when the wheel is sharp and thin, one can maneuver it smoothly, without hitting the sides or getting stuck. In grinding tea to powder, one should employ speed and power, since the longer it takes to grind, the more the metal can contaminate the color, especially if one is using iron.10

If the silk sieve is fine and taut, the tea powder will not clog the mesh. Do not be afraid to sieve the tea powder multiple times. As long as the thread is fine enough, the sieve will be light and all that much easier to be held flat and tight. Such a sieve can be reused several times without wasting tea powder or obstructing the openings. Finer, re-sieved tea powder tends to be lighter and therefore rises to the top when whisked. This forms a layer of foam, not unlike millet porridge, which focuses and reflects the color of the tea most beautifully.

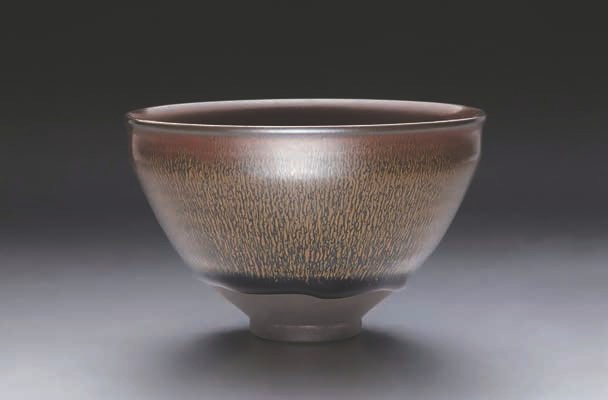

The most exquisite tea bowls are a dark bluish-black with delicate white highlights, called "rabbit's fur" or "marbled jade." Such bowls contrast with and heighten the whiteness of the tea froth. It is important for a tea bowl to be slightly higher and wider at the bottom than a rice bowl.1 The extra space allows for more breadth to whisk the tea, ensuring a fluffy, cloud-like foam to form over the tea. However, the proper size of a tea bowl shall truly be determined by the amount of tea one desires. If the bowl is too large for the amount of tea, then the color of the tea will not be fully enhanced. On the other hand, if there is too much powder in too small a bowl, then the tea will be gritty and not rise in froth.2 When the bowls are pre-heated, the foam will linger much longer.3

The proper size for a ladle is roughly what is adequate for a single bowl of tea.8 If there is excess water in the ladle, one will have to pour the leftovers back. If one ladle is not enough for the size of the bowl, then one will need to add another. Such adjustments delay the whisking and the liquor in the bowl shall grow cold.9

The whisk should be made of old bamboo4 so that the handle has a weight and bearing that firmly join it to the hand, making it fluid to maneuver. Furthermore, a heavier handle will generate momentum when it is being looped and twirled through the tea. In addition, the fibers of older bamboo stalks are tougher, which will add to the power of the whisking energy. It's important that there are spaces between the flanges of the whisk, and that these strong roots of the whisk taper down to sword tips. A sharp edge will be quieter, reduce splashing and help cut through the liquor to make the finest froth.

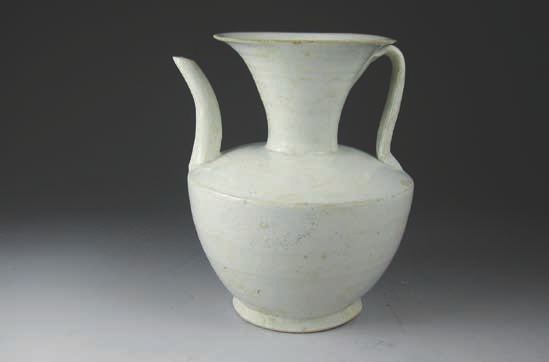

The finest water vases are made of gold and silver. The elegance in pouring will largely be determined by a long and graceful spout. The spout should be proportionate, with a straight curve and a larger base that tapers to a thinner mouth. A long, balanced spout that is well crafted will allow for skillful control of the water when pouring, and decrease the possibility of unwanted dribbles and splashes. In addition, the mouth of the spout should be tiny and oval with a teardrop angle. Such a vase will cut the water flow with ease, ending a pour without losing a drop.6 This is very important because it requires precisely seven gusts of hot water to create the perfect froth across surface of the tea.7 A single droplet of water would therefore disturb the foam whisked over the surface of the tea liquor.

The finest water for tea satisfies the following four elements: it is clear, light, sweet and pure. The first of these can be judged by eye. If the water is cloudy, it is surely low quality. Second, the lightest water is always better for tea.10 When tasting the water, there should be no foul, bitter or otherwise undesirable flavors. Third, fine water conveys a faint hint of a sweet aftertaste. And last but not least, the water has to be clean and pure, of course. Finding water that is clear, light, sweet and pure shall reflect the environment of the water source. Great water sources are few and far between. Legend has it that the waters of Zhongling, Zhenjing and Hui Mountain, Wuxi are the best, though these might, understandably, be thousands of miles away from one's home.11 Therefore, the best water shall be found in a nearby clean and clear mountain spring, while drawing from a well that is used often shall be the second best choice.12 Waters drawn from rivers and brooks tend to have an unpleasant odor, and are often muddy even though they may be light and and sweet. Therefore, the waters from streams and rivers are not often favorable for preparing tea. The water should be boiled to crab or fish eyes.13 If the water turns old, simply add fresh water and boil it again; then it can be enjoyed again.14

There are many different ways to whisk tea. In this dynasty, we've developed a new way to prepare tea, which starts by mixing the tea powder with a small amount of water. Some people pour hot water immediately after this, and start to whisk forcefully, and often with too light a whisk. More than likely, they will not achieve the finest foam, which should froth to the consistency of millet or the eye of a crab.2 This unfortunate situation is called a "languid point."3 If one fails to create the desired foam, it is most often attributable to one or more of these three errors: the hot water was added too early, the whisk was not heavy enough or perhaps the whisk was not handled with care. Beyond adding water before the tea powder has had enough time to dissolve, the whisking motions are often too vigorous. The result is a bowl of disappointingly dull green water without any white foam to speak of.

Another way to brew undesirable tea is to add hot water while the hand and whisk are moving intensely.4 In this case, some bubbly spots of froth might arise sporadically, but they shan't find one another and grow into a promising foam. These sparse bubbles are called "rising dough."5 The reason for this is that the brewer waited too long after the initial water was added to the powder or poured in too much hot water. It could also be because the wrist and fingers grasping the whisk are not limber enough.6 If the whisking is not fluent and uninhibited, the foam fails to grow into a thick layer of stiff froth that covers the whole of the tea liquor. Not only that, the commotion caused by ungraceful whisking leaves unattractive froth marks, called "legs," around the inside of the bowl.7

Masters will first stir the tea powder in the appropriate amount of water until the solution reaches a certain viscosity, akin to paste. Then, they will gently pour hot water round the rim of the bowl so slowly that the tea is barely disturbed. The whisking begins with a softness. The master's wrist will begin to gyrate in circular movements. The circles will then ellipse into larger orbits so that he can add more hot water to the tea. After that, the velocity will gather momentum. The fingers grasp the heavy whisk loosely yet firmly8 so that the wrist can swing, spin and twirl in full freedom and grace. The master whisks the tea to completion, not unlike the proper kneading of dough. Before you realize it has happened, foam arises like bright and twinkling stars shining in glory around the moon. At this point, the foundation of the tea is set. Just then, a second gust of hot water is poured into the bowl in a circular stream. This time, it does not need to be poured along the rim so slowly, but rather introduced swiftly and stopped just as abruptly. It is poured in so steadfastly that the surface of the tea is virtually untouched. After more powerful whisking, a greater foam will start to arise and pile up like a treasure of pearls. The amount of hot water in the third stream can be much greater. After that, the whisking fades to a gentler and yet steady pace. After whisking everywhere, even onto the bottom of the bowl, millet and crab eye appear. At this stage, the tea is two-thirds done. When it comes to the fourth gust of water, the master only adds a little. And as the ellipse of motion grows wider, the whisking also continues to slow down. More froth with colorful reflections, like cloud and mist, will rise up. Then it is time to add a liberal fifth shot of hot water, whilst gripping the whisk more loosely and continuously whisking throughout the whole bowl. If there is any place that the foam is too thin, the master will whisk in heavier strokes throughout that area. On the other hand, one should remember to wipe away excess foam if necessary. When the surface looks like a crisp frost or freshly fallen snow, then the tea has reached its peak. This is when the sixth gust of hot water shall be poured into the point where the froth is thickest, and followed by gentle strokes of the whisk around any creamy spots to even it all out. Then comes the final touch, but only if the tea seems too strong. If it is perfect to taste, then there is no need to add the last gust of hot water.9 In the end, there should be a cloud of creamy foam hovering above the surface of the tea, lingering, tumbling and billowing in puffs. This fascinating glory is termed "biting the bowl."10 The clear and light upper portion is for drinking.11 The Record of Tongjun says, "The white foam of tea is delicious and medicinal. There is no such thing as drinking too much of it."12

The most important element of the tea is the taste.13 There are four qualities in tasting fine tea: aroma, sweetness, substance14 and smoothness. Amongst all the teas under Heaven, only those from Beiyuan and Huoyuan meet all the finest standards in these four criteria. If a tea tastes rich, but somehow lacks substance, then the leaves were most likely over-steamed or pressed to hard. According to traditional medicine, leaves grow from a sour stem. Therefore if the stem is too long, the tea will taste sweet at first but in the end it will transform to a tart or astringent quality. Leaves that are broad, have stretched out and relaxed, taste bitter in nature.15 As a result, if the leaves are too old, they may taste of such a bitterness at first, only to transform into a sweet aftertaste. These are some of the issues that lower quality tea faces. However, there are extraordinary teas with the true fragrance and spirit of Nature as well.

The pure, unadulterated fragrance of a fine tea is greater than all the incense and perfumes in the royal cabinet.1 However, only those tea leaves steamed to perfection, pressed to the right degree to bring out the essences and remove excess moisture, ground and compressed in the same day will exhibit such excellence. When brewed, a perfectly made tea reveals the gorgeous and awakening fragrance of a crisp autumn breeze. On the other hand, tea that has too much moisture in the cake will smell sour and taste foul, in the same way that an almond that has been in a cracked shell for some time turns sour.

The best tea is pure white in color. Greenish-white tea is second best; grayish-white the third and yellowish-white the next. If Heaven bestows the weather, and all the processing steps are done with skill, then the leaves can be pure white. During the warm season, buds grow too quickly and there is not enough time for processing the leaves to the last on the same day they were plucked, and thus the finished cakes will be yellowish-white. If the leaves are under-steamed or pressed too lightly, then the cakes will be greenish-white. On the other hand, over-steaming will make the leaves grayish-white, while too little pressure results in cakes that are olive green. And if the cakes are over-roasted, they will turn out dark red.

Tea cakes that have been roasted multiple times become too dry on the outside and lose their fragrance in the process. On the other hand, leaves that are not roasted long enough will crumble, become spotty and taste weak. It is vital to dry the fresh buds to the perfect level, removing all the moisture without damaging the leaves. When roasting, one should build a fire in the center of the brazier first, then cover most of the wood with ash, while still leaving room for the flames to breathe. The ash should be scattered with a light touch to ensure the fire is not smothered. Let the fire burn for a while. After it has reached a stable balance, place the baking basket on top of the brazier. Dry out the basket first, before adding the tea cakes. Line up the packets along the walls of the basket, opening each one to expose the tea cakes inside. Do not leave a single cake covered by packaging paper.2 Flip the cakes frequently as they dry, and when they are done, wrap them back up as soon as possible. One should adjust the fire to the size of the basket and the amount of tea to be baked. The fire should never be so hot that one can't bear to place one's hand over the brazier without getting burned.3 Gently press the tea cakes every so often to see if they are only warm on the outside. Such pressure also ensures that the dry heat be evenly spread throughout the whole tea cake and dry out the inside as well. Some people think that tea should be dried at body temperature, but a flame burning at the temperature of a person can only dry the surface of a tea cake, not the inside. Then, one will be forced to roast such cakes again, lest they become damp or soggy. After all the drying is done, put all the re-packaged cakes in an old lacquer case and seal them.4 If the lacquer container is left closed when it is wet outside, then the tea cakes can be re-roasted only once every year and the color will remain as fresh as the day they were made.

The famous teas are made of the very best each region has to offer. For example, one can feel the effort and sacrifice in Taixing rock tea,5 cultivated on such barren, flat and rocky land; or Qingfeng Suicha,6 which grows on high cliffs, tastes stern; just as one may taste the innocence of Dalan tea,7 Xieshan tea8 blooms on islets and tastes alone. The light Wuchongzuo,9 also known as "Monks Walking on Water," seems made out of mulberry buds. Jiuke10 or Qiong tea11 is tough like the pebbles in birds' nests. One can taste all the glorious hues of a tea grown on a tree with colorful bark, as one can feel the fierce kindness of Tiger Rock tea,12 bestowed as a gift from our teachers; and the taste of mahogany13 is distinct in Wuyou Yenya tea,14 just as the vibrant verdure is there in every sip of Garden of Laoke tea.15 They each have their own specialties, which can never be found anywhere else, from any other maker.16 However, as time has passed, later generations of tea makers have begun to compete with each other, and the competition has taken a wrong turn. They have bought tea from one another, plagiarized each other and mixed their teas together. It is a shame that they have not realized that the beauty of a tea lies in the dedication to mastery over the meticulous process of finishing the tea.17 How can transplanting trees from famous places make one's own better?18 This is, of course, not the first time in history that famous teas have decreased in quality. And it is also possible for an obscure garden and tea maker to rise to fame after a few years of quality production. As a rule, reputation does not guarantee fine tea.19

Aside from the cakes made exclusively for the royal family, the rest of the tea is called "waibei,"21 the private sector. In general, privately roasted tea cakes have the following characteristics: they are made up of smaller bits, which are often of different tone and hue; the cakes crumble easily; and the tea tastes weak. Consequently, it should not be difficult to distinguish them from the royal tribute tea cakes. Lately, tea lovers have begun to fill their collections with privately baked tea. After years of watching the royal tea makers, such as those of Huoyuan, private tea producers have learned to mimic the shape and style of royal tea cakes fairly well. However, a closer look at what seems to be comparable reveals a substance that is very different. The color of such leaves might shine, looking fine at first glance, and yet the quality is ultimately inferior. The cakes themselves might be compact, but there is not any texture to them. And the flavor might come off strong, but it is heavy and lacks fragrance. How can they hide the fact that they are making inferior tea? In fact, other than the tea called "waibei," there is another privately produce tea, which is lightly roasted and called "qianbei." These lightly-roasted tea cakes are mostly produced near Huoyuan, so the quality is fairly good. The cakes are luminescent and white, and the liquor can indeed be whisked into a stiff froth. However, none of the four elements of a fine tea, namely aroma, sweetness, substance and smoothness, measure up to royal tribute tea. As this very nice lightly-roasted tea still tastes inferior to the royal teas, all the waibei teas should be even easier to discriminate. Some dishonest merchants add persimmon's buds into their cakes. Even though such cakes might look fine in appearance, when the tea is whisked, a cotton-like fiber shall appear on the surface and it will be difficult to create a thick millet froth. So when in doubt, put the tea to the test by giving it a whisk! The legendary tea saint Lu Yu said, "If the tea is adulterated with grass, leaves or anything else, those who drink it will find themselves ill." How can one not take caution with regards to what is in one's tea?

The End