|

|

As spring unfolds in full blossom, the outdoors call to us. We wanted to take our guests to make tea and see the unfolding buds of this year. And we thought that this would be the perfect opportunity to take you all along with us! What better way to start the 2016 tea season than with some fresh handmade green tea, full of the care and love of the residents and guests here at the Center? It was out of this desire to put our own effort and love into your Tea of the Month that we formed the idea of a whole issue devoted to green tea. Nothing inspires as much as contributing to this worldwide tea experience with our own hands.

We got up very early and headed off to Mingjian to meet up with Mr. Xie, whom many of you know and love. Aside from teaching us to make green tea and donating the leaf for this month's tea, he also agreed to finish the job, since we couldn't possibly finish enough tea for all of you in one day. (But our leaves and energy are all mixed in!) Mr. Xie is a very important part of the scenery at our Center, and will be very important for many of you as well, because so many of our visitors come here with a curiosity about how tea is processed. It is very important to experience with your own hands just how difficult it is to make tea, so that in your own soreness you will develop a tremendous respect for the Leaf. This respect isn't just in the billions of years of evolution, or in the Nature we always wax poetic about - the wind and rain, sun and moonshine, minerals, mountain and water that flow from roots to crown - it is also in the blood, sweat and tears of generation after generation of farmers. And there is a deep reverence in seeing just how much mastery, skill and art go into the crafting of the Leaf. And so, with great joy, we take as many of our guests as possible to a few different farms to try their hands at tea processing. It is amazing to make your own tea and take it home with you. If you didn't have enough reasons to come stay with us, here's another: Mr. Xie has formally invited each and every one of you to come to his farm and make tea, eat a nice lunch and take the tea you picked and crafted home with you!

Mr. Xie is a third-generation farmer in Mingjian, Nantou, Central Taiwan. Mingjian is lower altitude, in the foothills of the central mountain range. In the past few decades, such lower-altitude tea has been eclipsed by the popularity of the teas grown higher up. Though areas like Hsinchu and Miaoli counties (where Eastern Beauty is grown) have struggled since high mountain oolongs have come to dominate the market, Mingjian has prospered by providing lower-priced teas for export, or large-scale production for the bottled tea market (often called "Ready to Drink" or "RTD"). Mr. Xie's family has grown small-scale productions of oolong tea through three lifetimes, since before the higher-altitude teas even existed.

When we discuss organic farming and the need to make changes in tea farming - as well as other kinds of agriculture - it's important to remember that the farmers are always the first victims. It is they who handle the agrochemicals in large amounts, and most directly. Furthermore, it is only by humanizing and befriending them that we can bring about change. We must include rather than exclude - educate rather than ostracize!

Like so many other farmers, Mr. Xie started to get the nagging (coughing, wheezing) feeling that these chemicals were harmful to his family, his community and his land. When his wife almost miscarried their second child in 1997, he had had enough. Despite opposition from friends and family, Mr. Xie made a commitment to become an organic tea farmer, no matter the cost.

From 1997 to 2000, Mr. Xie and his family struggled to maintain their principles. His tea was sub-par and he lost almost all his customers. His father, who had been worried when he suggested upsetting the status quo in the first place, was very critical of his decisions. Organic farming is difficult, and it requires radical changes in farming and processing methodology - changes that would take time to learn. Rather than give up, as many would have done, Mr. Xie got a part-time job as a painter and carpenter, working day and night - either painting or farming - to keep his family afloat. Finally, in the early 2000s, his acumen for organic farming improved to the point that he was able to take his teas to market again. Since then, he has gone on to win awards, been featured on TV and has even heard his father, now a sprightly eightythree years old, bragging to others about how his tea is organic and good for the environment!

Mr. Xie's work hasn't stopped with his own farm. He knew that he would have to keep improving his skills, creating new and better teas, and to help show his neighbors the value of organic farming, especially since their land and his are close enough to influence each other. He formed a co-op with other farmers and began teaching locals to shift to organic methods, offering them equal shares in their combined enterprise. As more people have joined this local group, the incentive to do so has also increased. To date, more than twenty-five farmers in the Mingjian region are organic, including Mr. Xie's immediate neighbors.

Mr. Xie's kind heart shows in his teas. He cares deeply about Tea and the Earth. He produces green tea, large and small leaf red tea, as well as several kinds of oolong, and all with great skill. To us, he is an inspiration and a kind of hero - the kind not talked about enough these days. It's easy to follow the crowd and maintain the status quo, or to say, "I am just one person. What can I do?" It is difficult to face criticism from family and friends and stand up for what you believe to be right! The problem is that it is too easy for farmers to make more money with agrochemicals, and to do it with less work. And that's also why so many of them are over-using fertilizers and pesticides, reducing the average life of a tea bush to fifteen years, all in the name of personal gain. Many of them get cancer from improper exposure to such chemicals, themselves victims, as we mentioned above. Mr. Xie is a man who has seen a different way, and more inspiringly, lived that way and taught others to do so. And that is the true spirit of Tea!

In 1644, the Manchus once again conquered China, beginning the Qing Dynasty. Around that time, huge waves of immigrants moved to Taiwan to start a new life, often running from the economic and political problems resulting from such dynastic change. Most of these immigrants came to Taiwan from Fujian, one of the brightest leaves on the great tree of Chinese tea, for Fujian is the birthplace of oolong tea, as well as many other famous kinds of tea. Even today, it is a certain stop on any tea lover's tour of tea mountains, including Wuyi Mountain, where Cliff Tea (Yancha) is grown, Anxi, birthplace of Iron Goddess (Tieguanyin) and Fu Ding, where white tea comes from, etc... It should come as no surprise, then, that the settlers from such a tea land would bring tea with them, hoping to plant it on the magical island they saw shimmering above the mist, rising out of the ocean like the great turtle their beloved Guanyin rides through the Heavenly waters.

The tea that those early settlers brought thrived in Taiwan, especially in the mountains. The soil is rich in volcanic minerals and the mists that come in from the seas fill the valleys and highlands with the moisture that tea loves. The humidity, temperature, rainfall, mists and clouds as well as the gravelly soil are all ideal for tea growth - so much so that you have to wonder if the Fujianese found that out after they brought tea here, or if they brought tea after they realized how suitable the island would be for the cultivation of tea. Of course, the destiny of the tea trees was also rewritten by the journey across the strait.

One of the ancient names for tea is "Immovable." All the earliest tea sages had to find wild tea trees, gathering leaves like any other sacred herb. It took a long time for tea to be domesticated. For many thousands of years, tea trees were of the forest - a medicine that the shamans and Daoist mendicants sought out for its spiritual effects. Eventually, though, tea was domesticated, and then carried further than it could have spread on its own. Soon enough, tea was propagated on many mountains in China, and new varietals started to evolve, with amazing new characteristics, flavors, aromas and Qi.

As with many plants, every tea seed is unique, allowing it to rapidly evolve to new environs. And without any of the grafting technology used in plantation agriculture today, all the traditional teas were what we call "living tea," which, as many of you will remember, means that they were seed-propagated, allowed room to grow, lived in biodiversity, without agrochemicals or any irrigation, and were cultivated with respect. The early farmers quickly realized that when you moved tea to a new location, it changed completely to suit its new home. As a sacred herb, tea has always decorated Chinese relationships, from business deals to spiritual transmissions, offerings to the gods and even weddings. Even today, the Chinese wedding ceremony is centered around tea: the bride makes tea for the groom, and his acceptance of the tea into his body is an acceptance of his new wife. One of the reasons tea was used in such ceremonies is precisely because they also hoped these commitments would be "Immovable."

It should therefore come as no surprise that the tea trees planted in Taiwan quickly developed unique personalities due to the terroir here. It's amazing how quickly this happens, especially when skilled craftsman are involved. Not only do the trees evolve into new varietals naturally, but farmers begin to create new hybrids, researching the differences in search of wonderful new teas. They also adapt their processing methodologies over time, listening to how the leaves want to be dried. Great skill (gongfu) is always a listening to the medium. In tea brewing, for example, we try to brew the tea as it wants to be brewed. Similarly, master tea makers adapt their processing to suit the leaves, the season, the rainfall, and so on. Saying that they process the tea the way it "wanted" to be processed is perhaps misleading, but English lacks the proper sentiment. More literally, what we mean by this is that as new varietals evolved to new environments, influenced by the unique terroir there, the farmers also evolved their processing - testing and experimenting, "listening" to the results as they drank each year's tea, and slowly changing their methods to bring out the best in the tea. In fact, bringing out the best qualities of that varietal is what we mean by processing the tea the way it "wants" to be processed. You could say the same about brewing any particular tea.

Though you could perhaps call Si Ji Chun a hybrid, it is a natural, wild varietal that arose in Muzha. Since it is a more natural varietal, it is hardier than the other Taiwanese varietals. This is a testament to one of the principles we always promote in these pages when discussing living tea, which is that the leaves produced by man will never compare to Nature's. It is possible to further distinguish manmade teas by calling them "cultivars." These trees yield buds at least four times a year, which is where this tea's name comes from. "Si Ji Chun" might also be translated as "Four Seasons like Spring," referring to the fact that this bush can produce as much in other seasons as in spring, which is rare in the tea world. Si Ji Chun does not have a Taiwan classification number, since it evolved naturally. Si Ji Chun is more closely related to Ching Shin than it is to Jin Xuan or Tsui Yu, the other two "daughters" of Taiwan. The leaves of Si Ji Chun are round in shape, with veins that shoot off at 30-to 60-degree angles. The leaves have a light green hue, with less foliage, like Ching Shin. The buds of Si Ji Chun are often a gorgeous reddish hue when they emerge.

As many of you will remember from June of 2013, when we sent out this fabulous tea processed as oolong, Si Ji Chun has an exuberant, golden liquor that blossoms in a fresh, musky floweriness. It is tangy, with a slightly sour aftertaste, like the Tieguanyin varietal it evolved from. Many Taiwanese compare the aroma to gardenias. Of course, this month's tea will share some of these elements and have some unique characteristics since it is a green tea, not an oolong.

The guests who go with us to make green tea are always shocked at how difficult the picking is, no matter how well we prepare them. You pick and pick throughout the morning, and then take a glance down into your basket to see how you are faring, only to find that your basket is far more empty than you thought it would be - and not just by a small margin, but rather more of a "That's it?" kind of feeling. It's very hard work picking tea. And actually, our green tea is much easier than many kinds of green tea in the world because we are picking leaf and bud sets, as opposed to many green teas, which are composed of only buds. In fact, it can take as many as twenty thousand buds to make a single jin (600g) of tea!

You have to pick with fingernails, so you don't tear the stems. You want to squeeze the stem at just the right spot. When it is done right, it comes off as if it is given. There is a satisfying squishy feeling when you have released the stem in the best way. We started our day with prayers, offering our service to the tea bushes and asking for permission to share their medicine. And before we started picking, we asked the guests to respect the tea and remember this promise, allowing their heart to choose the proper bud sets to pick. In that way, the sensitive picker gets a real feeling that the tree is bestowing its buds on you. There is a fair energy exchange, especially in those moments when you choose the right stem and squeeze it to the perfect degree and in just the right place.

Traditionally, all-bud green teas would be considered higher quality. This is true, but only in terms of flavor and aroma. An all-bud tea will usually be more delicate and fragrant, since the cells of the tea have been less affected by withering. The issue of quality in green tea can be more complicated than just buds versus leaf-bud sets, however, as you have to take into account the weather, the varietal and the time of year the tea is picked. There are teas that benefit from having some leaves mixed in, as they can add breadth and strength, especially if you plan to brew the tea as leaves in a bowl. Of course, most of the time, mixing leaves in with the buds is done for economic reasons, since it vastly increases the yield of a harvest. Green tea farmers will often have a grade that is all bud and one that is composed of bud and leaf sets, which is available at a lower cost. In our case, the choice to use leaf and bud sets was based on two main criteria: First, it would have cost us more time and effort than we had to produce such a large quantity of all-bud tea. And second, we wanted some leaves in this tea because Si Ji Chun is a hearty liquor that responds to the added breadth, astringency and Qi. It makes more sense as a bolder green tea. Mr. Xie said that he wouldn't ordinarily make a delicate, fragrant green tea from these bushes. The decision to use buds and leaves together was, consequently, a mix of economy (more in time/effort than in money) and art - in terms of the tea we wanted to produce.

Whether your tea is all buds or bud-leaf sets will determine how it is processed. With all green tea, you want to arrest the oxidation as quickly as possible. In fact, the main difference between oolong and green tea is withering. Oolong is withered and shaken - the latter of which bruises the cellular structure of the leaf and encourages oxidation. Green tea, on the other hand, should progress to the kill-green stage immediately. Green tea can be baked, steamed or pan/basket fired to arrest oxidation. In Taiwan, green tea is pan fired the way oolong would be, as that is the more traditional tea processing method used here. The pan firing arrests oxidation and kills a green enzyme that makes tea bitter. In green tea, this stage is often lighter than other genres of tea. It is done at a lower temperature, but can be repeated several times in some green tea processing. You might wonder how the firing, or other kill-green (sa qing), "arrests oxidation" if there is no oxidation in green tea. Well, there is always some oxidation. The moment the leaf or bud is separated from the tree it starts oxidizing. And it will continue to do so as it sits in the basket waiting to be taken to the processing facility. However, the aim is to keep this duration as short as possible. We used a large wok to pan fire this month's green tea. It is a very difficult job, as you have to keep moving and not allow your hands to touch the pan. Even with the temperature turned down for our safety, it is still very hot. You must try to touch only the leaves, and lift them up without touching the metal, scattering them apart as they fall. You don't hear as much of the crackling sound you hear when firing oolong, as the temperature is much lower.

After the tea is fired, it is immediately rolled to shape it. This rolling would not be included in the processing if we were making allbud tea. All-bud teas are usually shaped by repeated firings, like the famous Dragonwell tea (Long Jing) of Hangzhou, which is pressed flat during firing. However, rolling is necessary when making green tea with leaves. With green tea, the rolling is more about shaping the tea than it is about breaking down the cells to encourage oxidation, as it is in oolong production. Even all-bud teas that have no rolling are in a sense "rolled," it just happens in the pan itself. They are shaped as they are fired, in other words. Like all the stages of processing tea, even a simple green tea, this stage looks easy when a master like Mr. Xie does it, but it is, in fact, very difficult. We roll the leaves across the mats, which curls the leaves into stripes.

After this, the tea is dried in an oven and we get a chance to sit and share some tea with Mr. Xie, discussing his experience and wisdom. Most all tea is dried similarly. It is roasted - traditionally over coals, but nowadays in an electric oven. It will be baked three to four times, depending on regional preferences and which varietal is used. Typically, tea is dried for an hour at around one hundred degrees centigrade. Then it is baked at ninety degrees for another hour, and then again at eighty degrees. If there is less leaf to dry on that day, or if it is all buds, that will typically be enough time, but for a larger quantity of leaf-bud sets, there is sometimes a fourth hour at seventy degrees. This will, of course, depend on the farmer's observations of his leaf. (Other kinds of green tea are dried in very different ways, as you will read about throughout this issue.)

"Stream-Enterer" is a bold tea with a deep Qi and strong fragrance. The varietal and processing result in a brisk, simple and pure green tea. It is the perfect way to herald the spring. As the first flush of the year, it sings of changing weather. It is Nature's expression of rising from dormancy to vibrancy, Yin to Yang. The flavor is sweet, yet bitter and crisp with astringency. You will find the energy expansive and uplifting, somehow purifying you and leaving you clean. If you can, enjoy this month's tea outdoors with some loved ones or organize a Global Tea Hut gathering at a park, by a stream or in your backyard. This tea is particulary suited to early morning or late afternoon/early evening gatherings. We hope you can also feel the personal love and tenderness in these leaves since we plucked and harvested some of them ourselves! The rest were made by Mr. Xie.

A thousand, thousand bowls And yet only one To enter the stream.

Leaves set adrift, Spinning and tumbling, Lofty and Low, From here all the way to the rain... If they come back, It won't be the same as before - It will be this very bowl!

Simple village brew Poorly steeped Bitter and strong So worthless Even a gem From the Dragon Throne Couldn't buy a bowl

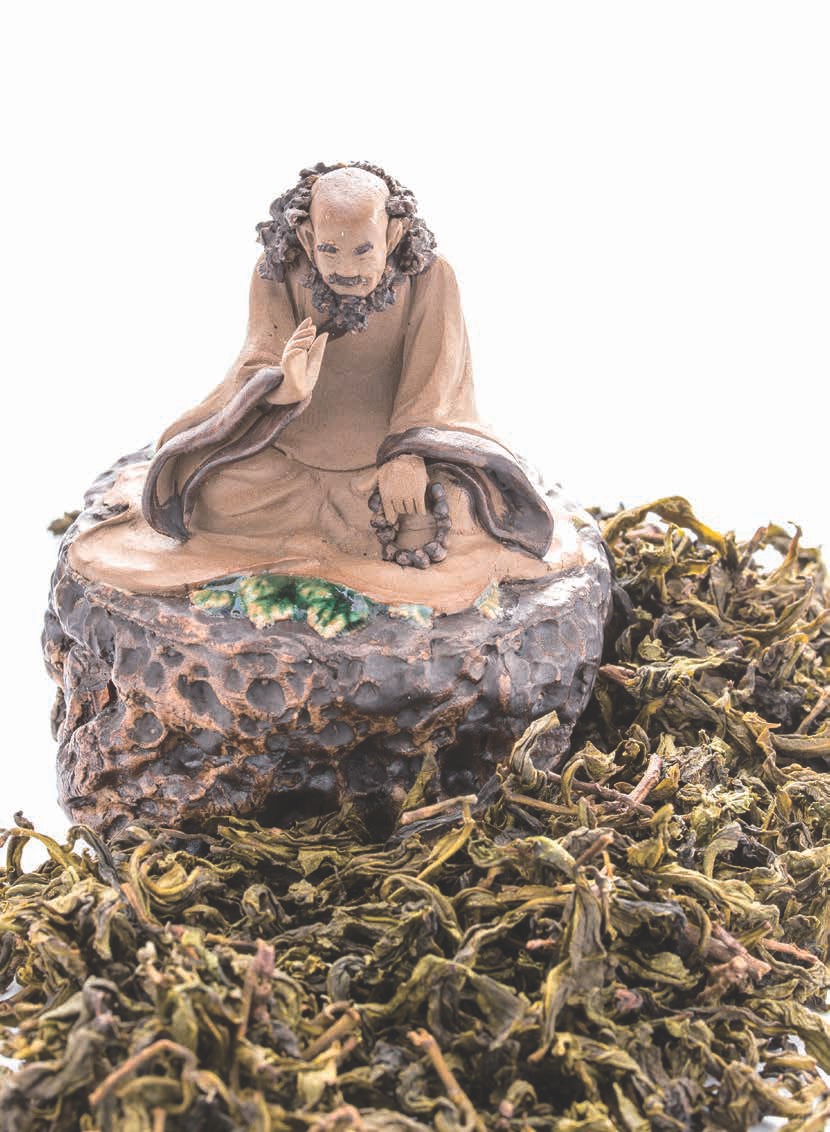

There is really only one way to brew this tea, and no matter how you drink it, do yourself a favor and save at least a few leaves to put directly in a bowl! There is nothing more pleasurable than drinking the year's first green tea in a bowl, watching the gorgeous green leaves unfold. The traditional character for tasting tea, "pin (品)" is composed of three "mouths," symbolizing that we enjoy tea with our mouth, nose and eyes. And in fact, you can learn to discern fine tea with these three senses. Actually, a tea session unfolds through all the senses, but certain teas, prepared in certain ways, will be more enjoyable to the nose, the mouth or, in this case, the eyes. Green tea is glorious to behold, and watching the leaves unfold is a huge part of enjoying a green tea, which is why many Chinese people drink their daily green tea in a glass.

Ordinarily, we want to use bowls with a lighter shade of glaze so that we can appreciate the tea liquor or leaves in a bowl. Though green tea leaves unfolding may be more beautiful than some other kinds of tea, all leaves in a bowl are beautiful, as is the liquor itself in steeped tea. It is therefore rare for us to choose a dark bowl, unless there is a good reason. Actually, when drinking a green tea like Stream-Enterer, it is better to use a dark bowl, as the liquor will be pale anyway and the dark color of the ceramic will highlight the bright green color of the leaves. The ideal is "Rabbit's Fur" glaze, which was popularized in the Song Dynasty. (We showed you some pictures of such bowls in April's issue within the emperor's Treatise on Tea.) If you have the chance, a real antique one will enhance your tea in ineffable ways. (You are all invited to the Center to drink some green tea in a Song Dynasty bowl during the warm months!) If you don't have access to a Rabbit's Fur bowl, antique or modern, choose any dark-colored bowl you can get and give it a try.