|

|

It is surprising how little information is generally available about the ways in which different kinds of tea are processed in different countries. Korean tea is particulary easy to explore because it is grown in a very small area and made by only an insignificant number of people. In China, there is a much greater variety of green teas, regions, varietals, etc. However, Korean tea is also rich in processing techniques, resulting in a greater variety of teas than one would expect.

The finest tea in Korea is entirely hand-processed. Perhaps that explains why there is so little of it - too little to be exported in commercial quantities. If you are visiting tea-growing regions, you will seek in vain for the room full of machines that so many Taiwanese and Mainland Chinese tea producers seem to take for granted. The most industry you will find in the tea-producing houses along the slopes of Hwagye Valley and the other tea-making areas of Mount Jiri is a row of gas rings under some iron cauldrons and a few rush mats for rolling the tea on. At first, it seems that all Korean tea is roughly similar in taste, even when it is processed using a machine in a factory. Yet there are a variety of processes, and of course the best tea is always handmade, even in factories.

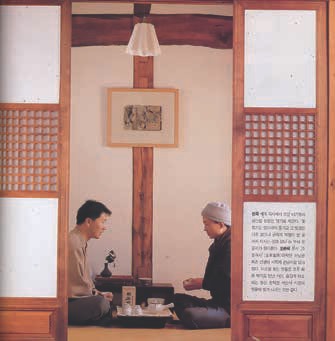

Nothing is more challenging than making tea by hand. Much of the finest tea is made by devoted laypersons and Buddhist monks, who regard the task as a spiritual discipline requiring great concentration. Certainly, no one can expect to earn money or fame by tea making; it can only be done as a labor of love, as a service to those who practice the Way of Tea. Some people begin each day's tea making with prayers, meditation and the reading of scriptures. The modern tea revival began largely among monks, who made tea for their personal use, with leaves from the bushes growing wild around their temples.

Ideally, perhaps, the person making the tea should also pick the leaves, but this is not usually possible. It is slow, wearisome work when the tea bushes are growing in irregular clusters up steep, rough slopes. The leaves must come from bushes that are located well away from any road, for tea readily absorbs the smell of exhaust fumes. Likewise, those making tea must not use any perfumed soap or cosmetics for the same reason. Externally and inwardly, there must be real cleanliness, simplicity of mind, and devotion of heart.

Korean tea is often classified according to the date at which the leaves were picked, as in the "first flush" system used since ancient times in China. Superimposed on the Korean lunar calendar are twenty-four seasonal dates based on the movement of the sun, which were borrowed from Chinese tradition. The day known as "Kok-u" normally falls on April 20th. The tea gathered before this date is known as "Ujon" and commands the highest price. The next seasonal date, "Ipha," falls on May 5th or 6th, and tea gathered between those two dates is known as "Sejak." Tea gathered after Ipha is known as "Chungjak." It should be added that the Korean weather is colder than that in China, with the result that Korean tea-makers, although they pay lip-service to the traditional dates, actually go on making "Ujon" from the first growth of shoots beyond April 20th, when sometimes there are almost no shoots on the tea bushes.

The leaves have to be carefully selected, especially when making the finest tea by hand. It is a little like wine-making, for certain patches of ground yield leaves that are particulary fragrant while other parts of the same valley or hill are incapable of producing tea of that quality. Some plantation owners apply liberal doses of fertilizer, which encourages the rapid growth of insipid leaves; obviously, there must be no trace of insecticide on the fresh buds used for making tea, but in some plantations even that is not guaranteed! People making tea need to check very carefully where the leaves they use have been picked from, if they do not pick their own.

Here are the different processes involved in making Korean teas:

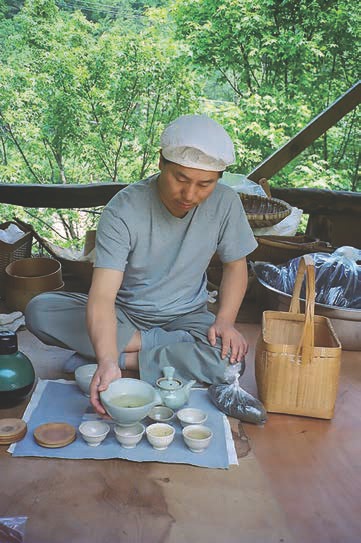

There are two main methods of hand firing in use in Korea when making the best green tea. One way of processing results in what is known as "Pucho-cha" and is by far the most common. This involves repeated transfers of the leaves to and from the cauldron, in alternating stages of heating and rolling, up to nine times. About three kilograms of fresh leaves are fired at a time.

The firing is done in a thick iron or steel cauldron, which is traditionally heated by a wood fire although nowadays a gas ring is often used, since that allows easier control of the temperature. The cauldron is first heated to about 350 degrees Celsius before the fresh leaves are tipped in. The leaves may emit a slight hissing crackle as they touch the hot metal. They must be tossed gently and stirred constantly to prevent burning. This softens them; then, once they have absorbed the heat, they can be briefly compressed and rolled together to encourage the evaporation of their moisture. Often two or more people work together to keep the leaves turning, hunched over the hot cauldron in what is a truly backbreaking task.

After an initial ten minutes or so of softening and heating over the fire, the leaves are removed from the heat to be rubbed and rolled vigorously by the palms of the hands on a firm, flat surface - often a rough straw mat or basket - so that they curl tightly on themselves. This encourages the development of an intense taste; but if too much violence is used, the leaves will tear and break and the quality of the tea will suffer. Speed and strength are both essential here.

The next step is the most delicate and time-consuming. The emerging juices make the rolled leaves stick tightly together, and they have to be shaken apart one by one in order that their moisture can evaporate freely. Without this, the tea cannot dry properly, and the final result will be clumped in unsightly knots, but if too much force is used, the leaves will tear and break.

Throughout the entire drying process, older leaves, twigs and harder stalks must continually be removed as they are noticed. The partially-dried leaves may next be spread out on a thin layer of paper laid on trays and left exposed to the air while other batches of fresh leaves are processed.

By the end of the first cycle of firing and rolling, the leaves have already diminished considerably in volume. They are now put back in the cauldron, which is cooler than for the first firing, though still quite hot. Again they are turned, pressed and rolled gently as the process continues. Then the hot leaves are once again removed from the cauldron, rubbed and rolled together on a hard surface, and shaken apart.

Once again, they are given a short time to go on drying in the air. Then the same process is repeated, several times, until they are virtually dry. The period over the heat is shorter each time, and the heat is gradually reduced.

The leaves are then spread out thinly and allowed to go on drying on sheets of clean paper spread on the heated floor of an indoor room for at least four to five hours, often overnight. The next morning, they are returned to the cauldron, which is now only lightly heated, and kept turning gently, all the time being stirred and pressed until the leaves are completely dry. This is the decisive final process, known in Korean as "mat-naegi" or "hyang-olligi" (taste-giving or fragrance-enhancing), lasting some two hours. As the final drying progresses, the leaves emit a pale cloud of intense fragrance. By the end, their color has changed from bright green to gray.

Once the tea is completely dry, it is given time to cool before being packed. This is important, since tea that is sealed too quickly may retain a taste of roasting that can spoil it.

Korean tea is not usually vacuum packed, but is sealed in foil bags containing thirty or fifty grams in the case of "ujeon" (first flush) and fifty or one hundred grams for other grades. The most important thing is to prevent any contact with moisture. The tea should be stored in a cool place. Once a pack is opened, the tea should be drunk fairly quickly, especially in the case of ujeon, which can easily lose its delicate taste once exposed to the air.

For the tea processed as "Chung-cha," represented most notably by the Venerable Hyodang's Panyaro tea, fresh leaves are plunged for a moment into nearly-boiling water to soften them, then allowed to drain on straw mats for a couple of hours before being placed over the fire.

Once in the cauldron over the fire, they remain there, and the entire process of rubbing and rolling, separating and stirring is done by two or three people bent over the cauldron. This process takes more than two hours for a single batch of about three kilograms of leaves. There is no further processing over the fire, but an equivalent prolonged period in which the tea lies spread thinly on a well-heated Korean ondol floor has the same effect of enhancing and deepening the taste.

One characteristic of the tea made by this method is its depth and subtlety, which can be developed by using relatively cool water for the first brewing and allowing the water for the initial brew to remain on the leaves for a longer duration. If the tea has been well made, the resulting intensity of taste is quite overwhelming. Sometimes it is mistakenly said that all Korean tea should be prepared in this way, whereas in fact normal Korean green tea should be made with hot (though not boiling) water.

"Ttok" (or ddok) is the Korean term for any kind of rice cake, whether the white stick of well-pounded rice paste broiled in peppery sauce, as "ttok-bbokki," or sliced into broth to make "ttok-guk," or the multiple sweet varieties that correspond to Western cakes. "Ttok-cha" is so named because it is a caked tea resulting from a similar process of pounding and shaping. It is an ancient tradition that has recently been revived and I confess that I have never drunk it, as it is quite hard to find.

Our fellow Global Tea Hut author, Steven D. Owyoung, explains it thus: "To make ttok tea, fresh leaves are picked and selected, and then the leaves were steamed in an earthenware steamer. The cooked leaves were pounded to a pulpy mass and the pulp formed into little cakes, some as small as the size of a coin. To dry and store, cakes were pierced and strung together on a cord, like a string of copper cash. This is why one traditional name for this tea is 'Cash Tea (Yopjon-cha).' "

The varieties of Korean tea are all worth exploring, though they are sometimes neglected in international tea communities. Being produced by hand in traditional ways and with a sense of spiritual presence means that Korean tea stands out from the bulk of mostly commercial tea, helping lead the drinker inward to the mountain stillness that is the tea's true source.