|

|

| Ordinary Treasure (Ping Fan Bao Zhang, 平凡寶藏) |  | Yiwu, Yunnan |  | 2004 Sheng Puerh Tea |  | Han Chinese |  | ~1200 Meters |

This month, we needed a tea that was perfectly suited for both bowl and gongfu tea brewing, to suit the theme of this issue. We thought about it for a long time and kept returning to one of the greatest gems of the Newborn Era of puerh, the 2004 Changtai Zhengpin. But how could we send that tea out? As you will see, one of the things that makes this cake so beautiful is that the puerh boom and the mainstream market skipped over this tea, making it a very affordable choice at the time. Even now, though it has increased in value, its inflation has not been commensurate with other teas produced during the same period. Though it is less expensive than other tento twelve-year-old teas, it is by no means within the range of what we can afford to send to so many hundreds of people around the world! And yet, it is the perfect choice...

Eventually, we visited our old friend Mr. Liang, whom many of you will remember as the guide for our 2013 Global Tea Hut trip to Yunnan. We told him about the topic of this issue and that we were hoping to offer the Zhengpin to all of you. He smiled, building anticipation for a silent cup or two, and then agreed to donate as much as we needed so that this month would be an abundant one. Whether you prepare this tea in a cup or a bowl, be sure to raise one to Mr. Liang, whose generosity has made this month's adventure possible!

If we are wise, we learn to revere the ordinary love and support of the people and things that encourage and sustain us every day over the special, extraordinary situations and people that pass through our lives briefly. For example, we love the water that we gather from the spring each week at the Center far more than some of the best waters we've had when traveling on the Tibetan plateau. Yes, the waters up there were better, but these waters nourish all our tea, week in and week out. Similarly, there are teas that we have drunk so many times over the years, growing a deep an lasting intimacy that makes them much dearer to our hearts than the very special, rare teas we only drink on special occasions. We often take such things for granted, even though we know better deep down. This month's cake is one such tea - a tea we've shared hundreds of times, and in every way possible: sidehandle, gongfu, boiled and shared roadside to passersby, etc. And that's why we call it "Ordinary Treasure." Some of you who have been around long enough will even remember that this tea, mixed with the herb Qi Lan (which we also love to add to it) was our second ever Global Tea Hut Tea of the Month - way back in the "newsletter" days of early 2012.

As a brief intro, and because we all need to return to the basics and refine our understanding, let's discuss puerh tea as a contextual background for some deeper explorations into Changtai, Yiwu and this cake in particular.

All puerh comes from Yunnan, the birthplace of tea. There are two kinds of puerh: sheng and shou. Sheng is the more traditional, greener kind of puerh. It is picked, withered, fired and sun-dried. Sheng tea is then naturally fermented over time, and the older the better. It miraculously mellows from green, powerful, astringent tea to a deep and dark elixir. It also changes from "cool" to "hot," in the Traditional Chinese Medical sense of the words. Shou tea goes through an additional step after the ordinary steps listed above. It is piled under thermal blankets in order to artificially ferment the tea. Aboriginals in Yunnan had many ways to turn their tea to warm (again in the TCM sense) including baking, roasting, or even burying it in bamboo. However, the modern method of piling the tea was developed and then commercialized in 1973 by big puerh factories in an attempt to reproduce the amazing effects that time and natural fermentation have on tea. Of course, they only succeeded in inventing a new genre of tea, rather than actually achieving what nature does over such long periods of time. Succinctly, the difference is that sheng puerh is left green, which means it ages naturally over time (which takes seventy years to reach full maturity) and shou puerh is artificially fermented in piles (which takes forty-five to sixty days to fully ferment the tea). This month's tea is a sheng tea: picked, withered, fired and sun-dried. It dates to the year 2004 and is from the Yiwu mountain region.

The most distinctive steps in puerh production are the sa qing (kill-green) and sun-drying phases. The firing, or "sa qing," comes after withering. It is done to arrest the oxidation begun in the withering and to "kill" certain enzymes in the tea that make it bitter, which is why it may also be translated as "de-enzyming." In puerh tea, the de-enzyming is done at a lower temperature for a shorter duration because some of these enzymes are important for the fermentation of the tea, which happens in post-production (either naturally or artificially). This also ensures that heat-resistant spores will survive and flourish, as the bacteria and mold are the source of the fermentation. The sun-drying also facilitates and encourages fermentation by reactivating the microbial worlds that live in the leaves, going about their days in Horton Hears a Who style.

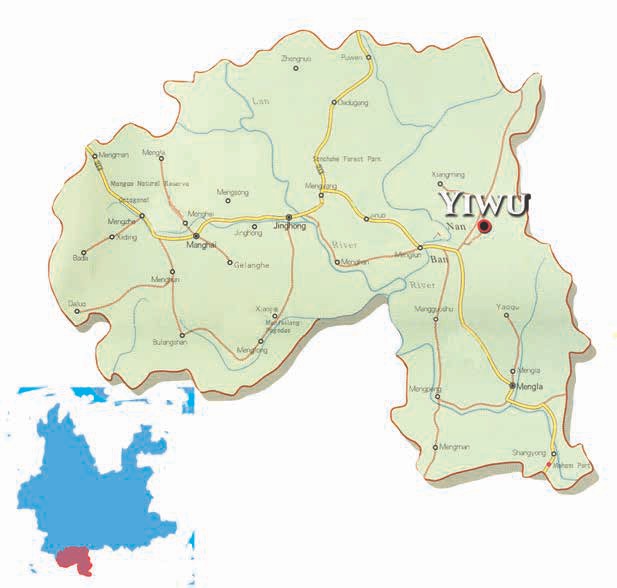

The Yiwu tea-growing area is located in the Yiwu Township of Mengla County. The greater Yiwu region encompasses the four townships of Mansa, Mahei, Yitian and Manluo. In ancient times, local ethnic Bulang people were the primary growers of tea there. By the end of the Qing Dynasty, large numbers of Han merchants had arrived in Yiwu and begun growing tea. They founded businesses to engage in the tea trade, establishing a collection point among the six famous tea mountains. In practice, the Yiwu tea district also includes Mansa Tea Mountain. Today, the Yiwu tea-growing areas are approximately 15,000 mu (1 mu = 1/6 acre) in size and produce approximately 600 tons of tea per year. These areas lie between 820 and 2,000 meters in elevation and have a very marked topography. Yearly rainfall is between 1,000 and 1,800 mm. There are between 1,600 and 2,000 hours of sunshine per year and a relative humidity of 80%. The weather is warm and humid all year round with no frost, making it one of the most ideal tea-growing regions in Yunnan. Yiwu has become the iconic area of Xishuangbanna, the most prominent of the four tea-producing prefectures of Yunnan (the others being Puerh, Lincang and Dehong).

Because there is so much dishonesty in the puerh market, learning to taste the regions is important for the ardent explorer. Though Lao Ban Zhang village produces only approximately seven tons a year, as much as three thousand tons will be sold with labels declaring them "Authentic Lao Ban Zhang Tea." Yiwu is a very good place to start one's tasting journey, as it has some very distinct characteristics, all of which you can look for in this month's tea. Yiwu tea is very thick - perhaps the thickest of all puerh. The liquor is viscous. When you look in the cup, it has the appearance of honey or oil, with a very thick surface that reflects the illusion that it is much more syrupy than it actually is. Yiwu tea transforms better than many teas, which means the flavors change quickly from astringent to bitter, then to gan (fresh mintiness which is more of a sensation than a flavor), and then from sour to sweet. Yiwu tea also coats the mouth and throat a bit more than most puerh teas. These two qualities, of transformation and coating, are not, ultimately, defining, however, since many fine teas will share these characteristics. Nevertheless, they are overtly present in Yiwu teas. Finally, Yiwu tea is most easily recognized by a raw honey aftertaste. The aftertaste reminds one of the kind of honey produced by wild bees that take pollen from lots of different flowers - rich, raw and sweet with hints of grass and hay. Fine Yiwu tea will have all the Ten Qualities we discussed in previous issues, and when it is right it is really right. Fine Yiwu tea is among the best Yunnan has to offer.

Since the puerh boom, much of the Yiwu region has become overcommercialized and the quality of tea has decreased as a result. Generally speaking, 2004 was the last year before this major shift. Of course, there are exceptions on both sides: factories/farms that had shifted towards less environmentally ethical principals before 2004 and great, sustainable teas after 2004, like many of the wonderful old-growth cakes that come out of Gua Feng Zhai, for example. Still, there was a change around this time, as more big factories built plantations and began using pesticides, weed-killers and chemical fertilizers to meet the growing demand for puerh tea. Many of these unhealthy practices started earlier, but only in earnest after the mid-2000s when the market was large enough to warrant the expense of such farming and the agrochemicals that go with it. This doesn't mean that all pre-2004 tea is clean, but there is a much better chance that it is. And it most certainly is if it comes from older gardens. Actually, Changtai, as a brand and a factory, exemplifies this change quite well, as it began by producing small runs of extraordinary old-growth puerh from Yiwu.

The Changtai Tea Company started with the Yichang label, which took the puerh world by storm and carried a small, local Yiwu factory to stardom. The 1999 Yichang cake is still a benchmark of the best Yiwu has to offer. Immediately after its rise to success, Changtai established a new factory in the Xiao Jinggu tea region at the end of 2000. Starting in 2001, they released a series of Changtai Label teas, using the some of the best quality raw tea from large trees in the Jinggu region. In 2003, they released the Round Clouds and Mist series, using materials from the Menghai region. Even though they started with relatively strong bitterness and astringency, over the course of these ten years of aging, many of these teas have already started to have an old Menghai flavor. The Teas Under Heaven series, the Chen Hong Chang series, the Jinggu label series, and the Origins of Si and Pu series also have some relatively decent examples within them.

Starting in 2003, Changtai started growing as a company and factory, and, as with most things, quality decreased as quantity increased. It is now one of the largest puerh factories in the world, and we don't own any of their teas from 2004 onwards. In fact, you could say that their peak was that first, amazing cake in 1999, followed by some very nice Yiwu cakes, then some decent series from other regions, ending their streak of really fine, quality teas in 2003. Not every Changtai tea made between 1999 and 2003 is a gem. Many are just decent. Some of them are neglected prizes, as they are often organic, and sometimes include old-growth raw material. And aside from the 1999 Yichang Hao, many early Changtai cakes are quite affordable compared to other cakes of equal age.

One of the things that makes early Changtai tea special is that they processed old-growth tea in very traditional ways, including using wood-fired stoves to create the steam used to compress the cakes. Through several experiments, we have found that tea produced on the mountain where the tea comes from, with steam for compression from the same water that the trees drank from, will be better than when the tea is transported to a factory and blended/compressed there.

In the end, Changtai is a tea business like any other. It is not worthwhile to criticize brands or companies; rather, we should focus on the behavior itself. As tea lovers, we can't be brand-champions. Here at the Center, we are environmental champions. We seek quality tea made in sustainable ways. We are on the side of Tea Herself. Some early Changtai products are nice and made well, with clean tea, but their modern practices are not as commendable. Still, it is through inclusion that we change the world, not exclusion. We invite Changtai to join in the sustainable revolution! Being against anything will only increase the separation that is the world's greatest problem. Let us therefore awaken all our tea brothers and sisters, and bowl by bowl, cup by cup, we can indeed change!

Though our Tea of the Month, "Ordinary Treasure," does not fall into the years when Changtai was producing its highest quality puerh, it is an overlooked gem. It is real Yiwu tea, with some old-growth blended in, cultivated without any chemicals and processed in traditional ways. The mainstream puerh market passed it over, as an onslaught of new teas were being produced by many factories at the time. Even now, many puerh lovers don't know about this tea. And that, ultimately, is one of the main reasons why it is such a great tea: it is affordable! The inflation of puerh tea, especially aged cakes, has taken some of the spirit out of tea, making it harder to enjoy, share or use in offering hospitality to one's guests. Having a nice puerh that is more than ten years old, clean and relatively cheap means you can enjoy this tea often, share it and even put some aside to age. It is, therefore, a treasure indeed!

Every five to seven years, puerh tea turns a corner in its aging process. This tea has been stored rather dryly and has therefore just begun to turn the second corner into adolescence. Tea of this age starts to have hints of age, with spiced, mulled flavors, like sandalwood and mahogany. It has changed a lot over the years, taking on a richer, oilier depth as the years have passed. Like all good Yiwu tea, Ordinary Treasure is full-bodied and thick, with a rich and sweet aftertaste. It coats the mouth. Whether you brew it gongfu or in a bowl, Ordinary Treasure has a deep and serene Qi that relaxes you, pacifying the day. It is great drunk in the afternoon, especially if you have a few hours to relax with some friends.

We hope that this month's tea is a wonderful chance to share some slightly aged puerh with your loved ones. You can learn a lot about how puerh changes over time by drinking examples stored in different conditions and at different ages. This tea is a good standard for tenyear-old tea, as there are much finer and much worse teas from the time period. Let that remind us that some of the most amazing things in life are such because they are ordinary, day-to-day friends! And this 2004 Zhengpin is one of our allaround best friends.

I found this tea incredibly energetic, especially brewed gongfu style. The fifth infusion eased me into a grounding, deep meditative emptiness, but by the tenth infusion I felt light, fluid, airy and active.

After climbing one thousand stone stairs to fetch spring water, we returned to sit for a gongfu session. The Yiwu tea seemed to move across my palate with speed, not lingering on any specific note. The loving nourishment I found in this tea was noticeable, leaving me feeling warm and supported. I had a similar feeling the previous day when we steeped it with a side-handle: The tea was less refined, but still held that same expansive motherly nourishment. My conclusion of the two separate brews is that I like this tea lots.

As I bring the cup up and breathe in, a subtle warmth fills my nose. I know I will need to go down to the tea, so I inhale deeply. There is an expansion of aroma into the forehead. After finishing my first cup I sit quietly and realize a tingling at the back of my nasal cavity. Flavor and aroma seem to be moving from my mouth into my nose in a way I have not noticed before. This is one of the Ten Qualities of a Fine Tea that had experientially eluded me until now. It seems this tea not only coats the mouth, but the aroma coats the nasal cavity as well!

When we drank this tea as bowl tea, I felt the dawn and the sun slowly rising. I was sitting next to a softly rushing river, the smell of campfire smoke lingering in the air. I felt rested, cozy and quiet. When we drank it gongfu, it was resilient, lightly splashing up to my upper palate. The five flavors fully encompassed my mouth. Both were lovely sits. When brewing this tea gongfu, I was able to recognize the pungent honey aftertaste that is characteristic of Yiwu tea, which came on more prominently in the later steepings. I often seem to miss this in bowl tea.

This month, the most important thing you will need advice on is whether you should brew this tea gongfu or sidehandle (bowl tea). Choosing your brewing method will set the tone for the session, be instrumental in composing your chaxi and will determine the way the tea feels and tastes as well. There are several approaches we use to decide which brewing method is appropriate, but you can also use your intuition.

At the Center, the most obvious determining factors for choosing between gongfu and bowl tea are the number of guests and quality of the tea. Gongfu tea is much more suited to intimate gatherings. Unless we are teaching a class, we would never choose gongfu tea for a gathering of more than five or six people. This makes bringing the cups in and pre-warming them a bit of a chore, and the time it takes to do so starts to influence the tea, which can easily oversteep and/or cool down. We do often brew gongfu tea for more people, but only educationally. Also, the quality and kind of tea are determining factors for us. Tea above a certain quality demands gongfu brewing (with rare exceptions). This is because gongfu brewing brings out the best in a tea, and very rare treasures that won't have many more sessions on this Earth deserve to be brewed with all the skill we can muster. Certain oolong teas also are better brewed gongfu, as oolong tea and gongfu tea grew up together and are lifelong lovers. That said, we do like to throw a few balls of oolong in a bowl and watch them open!

Aside from quality and the number of guests, you can also decide which brewing method to use based on the energy of the session. If you are trying to create a more ceremonial, meditative space, you will want to choose bowl tea, but if the tea is the focus and you want to treasure each sip, gongfu is the obvious choice. Don't feel like every tea session needs to be silent or reverential. Tea is very much about connecting to others as well. Sometimes we have tea to make new friends or celebrate our old ones, to resolve issues and to have long, important discussions with our loved ones. In such a tea session, where the tea is not the focus, but rather a background comfort that helps create heart space, a simple tea in a bowl is the obvious choice, especially since gongfu brewing demands more attention. There are other ways and means of choosing whether to brew this month's tea, or any tea, gongfu or bowl, but these will help you get started!