|

|

The four favorite pastimes, or rather, the cultivated interests that any scholar in pre-modern China would enjoy are the Qin (Chinese zither), calligraphy, painting and qi (Chinese chess), and they were sometimes thought to be ranked in that order of nobility, as was the sophistication and loftiness of the one who appreciated each. Therefore, playing the Qin was actually much more than learning a musical instrument. But what stands beyond just playing the notes correctly? In this article, we'll explore some of the many cultural melodies that have resounded from the Qin into and throughout Chinese history for thousands of years up to the present, as the zither's haunting vibrations surely still echo through the old mountain crags and peaks.

Even though there is no record of this instrument in the most ancient Chinese classics, there are several stories about how different legendary sages invented the Qin more than four thousand years ago. The insistence on a relationship between the Qin and the earliest saints and rulers shows the importance of Qin in Chinese history. Tea was similarly fastened to the ancients' hagiography as a testament to the Chinese reverence for the Leaf.

The earliest written record of the Qin is found in the Book of Poetry, which was collated between the eleventh and fifth centuries B.C.E. From that time, the "masters of the Qin" were granted titles in all the feudal lords' courts. Even the most famous philosopher and educator, Confucius, studied the Qin with a master, in part to learn how to recite poetry properly, as Chinese poetry is often recited to music. At that time, string and percussion music was performed during court rituals exclusively, and was very different from the brass music which was performed during funerals. Therefore, the Qin is loaded with symbolism regarding cosmology, ethics and propriety: the five strings symbolize the five elements, while a seven-string Qin symbolizes the five elements plus the king and the officials; the thirteen frets symbolize the lunar calendar, or the solar months with the king at the center; and the three ways of plucking the strings symbolize the perfect harmony of Heaven, Earth and human beings. The Qin was regarded as a very serious practice; it was never intended to entertain others or relax oneself. It was, instead, viewed as a means of self-cultivation, a Dao. And that is where it meets Tea, since Tea was also viewed thus for thousands of years before it was ever recreationalized. Though both the Qin and Tea have fallen into the hands of enjoyment and casual use, we shouldn't forget their sacred heritage.

During the time between the third and the sixth centuries C.E., there were constant wars and China broke into several small, independent kingdoms ruled by nomads. Throughout this chaotic period, officials and powerful families had to flee their luxurious mansions to survive. It was at that difficult time that the literati who had lost their official positions and the comfort of city life turned to playing the Qin in reminiscence of their glory days. The loyal literati preferred to sequester themselves in remote mountainous areas to practice self-cultivation rather than serve foreign kings. This was in harmony with the predominant Daoist philosophy of service to one's country and lord when needed and spiritual cultivation when one wasn't needed. As a result, playing the Qin was more and more regarded as an aspect of the holy man's life in the mountains - lofty, erudite and a symbol of integrity. A new dimension was added to Qin music during this unfortunate period of turmoil. Rather than playing the proper, elegant music of political rituals, these musicians found the expression of Nature, Daoist principles and spirit in the strings of the Qin, as well as a bittersweet catharsis in the sad music that expressed their displaced hearts.

Then we come to the lively and free-spirited Tang Dynasty (618907), when all things artistic flourished as never before. The most popular activities at literary and political gatherings were composing poetry, drinking tea, and playing the Qin. This might remind Western readers of Mozart playing the violin for aristocrats all over Europe during the eighteenth century. For the European aristocrats and commoners alike, most of Mozart's music was pure entertainment. Playing music was not necessarily a symbol of cultivation, nor did all gentlemen know how to play the violin or piano. Though the aristocratic parties may evoke such an analogy, in China, the Qin was ever and always a form of high art that could only be played well by peaceful, tranquil, well-educated and well-disciplined sages. Perhaps Mozart's requiems would be a more apt analogy if they too had been played at small gatherings where the listeners had approached the experience with the reverence they would have had in church.

One of the reason why the Qin never made its way into popular entertainment is that the sound of the Qin is neither vibrant nor loud enough. As a result, most Qin music is relatively slow and solemn. In other words, one needs to be very concentrated and well-composed (no pun intended), to practice something that is so soft and calming for long periods of time. By the same token, it takes a tranquil and settled mind to appreciate this kind of slow, ethereal and quiet music. You cannot talk or laugh during a Qin performance. It settles the heart and calms the mind, much like a fine cup of tea. The Qin transcended the social milieu, pushing aristocratic gatherings into a spiritual space. As testament to the Qin's place beyond social mores, the Qin was not just played by men in that era, but women could also cultivate a Qin practice in their leisure time. In the eighth century, the court official and painter, Zhou Fang, brushed a delightful painting of several lavishly dressed ladies enjoying elegant Qin music while sipping tea in their beautiful garden. The Qin clearly transcended such boundaries.

As an acquired taste, it is no surprise that the Qin was mostly popularized in elite literati circles and seldom made its way to the general public. It remained the instrument of the spirit, carried by Daoist mendicants from peak to peak and only understood in the city (if at all) by those educated enough to at least look out longingly and with a poetic heart at the mountains the sages cloudwalked. When a group of elites had an outing to drink tea at their favorite sites in the mountains or by creeks, someone would invariably bring a Qin to share soothing music while enjoying fine tea in a lovely environment. In those days, tea was very often enjoyed in Nature, as people had the luxury to do so. This is something we, in this age, need to learn from. The loss of our glorious Nature is a sadness the modern Qin master might lament in song.

The Qin has always been played by sages and sensitive beings, not performed by musicians. It is not that aristocrats would not listen to musicians, even on outings, but rather that the Qin was never used to entertain friends or to excite and energize a crowd. You don't party with the Qin, in other words. The Qin was an alternative way to share a subdued and cultivated sentiment of joy amongst friends, enchanting and eliciting the Nature around them, expressing deep profundity and capturing more than what words can convey in heart-to-heart messages. In that way, the Qin shares this all with tea, which was very often drunk in the same spirit. Tea, also, can convey that which is beyond words, as it, too, can be a means to cultivate one's spirit and express one's insights to others. If one is emotionally balanced and disciplined, then there is no need to relax, as one is always in a state of grace and peace - a peace that can be shared with others, which is the true spirit of Tea and of the Qin, alike.

Entertainment in those days meant taking turns composing poems and drinking wine and other kinds of music and mirth. To be sure, poetry brought delight and tears of joy to even the most serious politicians, but they need not have taken the trouble to hike a long way to a remote place to look for entertainment that they could have pursued in the comfort of their homes. Serious poets, painters, calligraphers, Tea and Qin masters sought the mountains for communion with Nature, and because their art was both a means of cultivation and an expression of it.

After the Song Dynasty (9600-1279), Confucianism reclaimed its preeminence at court and literati culture evolved to a pinnacle, epitomized in Chinese history. Consequently, the zeitgeist of Song Dynasty art is delicate and minimalist in its ideal, yet intricate in concept. The Qin fit in with this aesthetic, symbolizing the essence of high art: the sound of the Qin is delicate, solo and minimalistic, and yet the composition of the music can be complicated and sophisticated with profound implications. Even though the sound the Qin makes can be perceived as simple, it is compensated for by an elaborate and complex arrangement of notes. This aesthetic, mastered during the Song, is the first level of beauty expressed by the Qin, which is the harmony between the tangible (sound) and the intangible (composition/spirit). To the Chinese, these elements were not contradictory at all. On the contrary, they were viewed as yin and yang, complementing each other to make this art form complete, exquisite and perfect. If both the sound and the spirit were simple, then the music would be boring. However, the combination of a refined timbre and elaborate melody with simple sounds creates the most aesthetically pleasing balance between two seemingly opposite elements.

The leading poet/calligrapher/ painter/official/scholar/sage/and, yes, Qin master in the Northern Song Dynasty, Su Dongpo, wrote a short and seemingly simple poem on the Qin which helps capture some of the spiritual sentiment that has over time accrued to this majestic instrument: "If the sound is from the Qin, then why is it quiet inside its case? And if the sound is from the tips of the fingers, then why don't we hear the fingers alone?" Su points out that the music does not exist in either the strings/ instrument nor the fingers/master. To phrase it differently, it is the combination of the perfect touch of the fingers in the correct positions on the strings for the precise duration of time that creates a transcendent melody. In the same vein, the instrument itself is but wood and strings of silk, though not all Qins are created equally - there are superior and inferior ones. Likewise, not all people who practice the Qin can reach the same proficiency in playing.

Like tea, every fine, infinitely subtle element in the quality of the instrument and any minute difference in the fingers and maneuvers all tremendously affects the quality of the performance. Also like tea, the most important element in mastery of the Qin is the mental state of the player, which is not visible but audible. It requires a tranquil, still, patient and disciplined mind to master the Qin, as does tea preparation. Furthermore, even a skilled player with a good technique will reveal the slightest emotional unbalance in a performance. This is also why tea was served in Zen monasteries, as a naked representation of the heart-mind that cannot be covered with masks, but reveals the true level of one's cultivation.

Su Dongpo, the greatest of the literati of the Northern Song Dynasty, pointed out a philosophical issue in art/aesthetics with this simple poem. By making readers realize that the visible elements are not all that counts in music, they are forced to ponder the essential factor in music, which is the personality/ psyche of the player. At this point, we see the second layer of beauty in the Qin, which is the fusion of the instrument and the player, i.e., the visible (the quality of the Qin and the technique of the player) and the audible (the player's emotional state). It is the perfect union of instrument and player that moves and soothes people.

The last emperor of the Northern Song Dynasty, Huizong, was such a connoisseur of almost all forms of art that he lost the Chinese empire to a nomad from the north! Many of you will remember that we devoted the whole of April's issue of Global Tea Hut to this marvelous man, including an annotated translation of his Treatise on Tea. Due to Huizong's fervent love for art, he made painters officials at court, founded a royal studio for making Qin, founded several royal kilns, invented his own idiosyncratic style of calligraphy, wrote about tea, and much more. As you can see, in the Song Dynasty, even the emperor was more than simply an ardent art aficionado, but a true artist himself, and in many disciplines no less. One of the reasons why the ancients were so skilled in so many areas was that they understood the essence of art itself, which translated and transmitted mastery quite fluently from one discipline to the next. They understood that mastery of the self was the essence of art - that spiritual cultivation was the soul of an artistic life, both informing and refining discipline in any art form, from poetry to tea to the Qin.

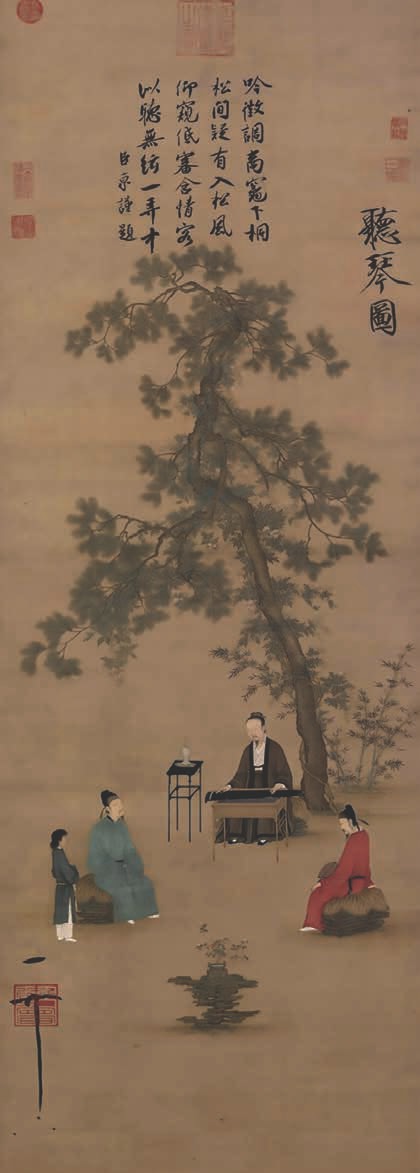

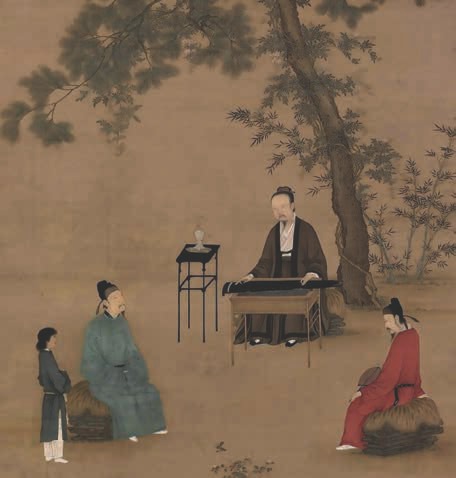

Once a master has attained a certain level of concentration, internal harmony and spirit, it is relatively easy for her to master skills in different arenas, be it calligraphy, painting, tea or Qin-playing. Emperor Huizong painted a portrait of a gentleman playing the Qin under a pine tree while two officials sitting on rocks listen to the lofty music. The loftiness is signified by the pine tree, which does not wither even in harsh, freezing winter. Another painting by this artistic emperor depicts a lavish tea party for scholars with many snacks and servants. Tucked in the upper left side under some tall trees is a Qin waiting to be played after the feast. It is apparent that the gentlemen enjoyed playing the Qin after a relaxing tea party. (Both of these paintings were also printed in April's issue.)

As the poet Su Dongpo pointed out, the essence of Qin music lies neither in the instrument nor in the player's fingers. It is, rather, the perfect harmony of both that makes Qin music so exquisite. In the same way, fine tea is not just good tea leaves nor good water alone; it is the perfect combination of the tea leaves and water that makes brewing tea such an art. There is much more beyond the teaware and tea. Su's poem could be quite aptly applied to dry tea leaves, which will not produce fine liquor on their own, and to the water that is yet to be infused. It is through the subtle meeting of the two, which itself happens physically and spiritually, that the tea is made. The Qin and tea are equally mystical in their alchemy, to which Su's poem alludes. When it comes to deciding on the right tea for a gathering and making minute adjustments in brewing, the heart of the brewer shines through.

In fact, this concept of fusion between the material and the master is not exclusive to Eastern art and philosophy. One of the most beautiful souls to walk this Earth, Helen Keller, once said, "The best and most beautiful things in the world cannot be seen or even touched - they must be felt with the heart." Truly, this sentiment is cherished without geographical or cultural restrictions; it is universal, and precious to us all. As long as you are willing to still your mind, you also will enjoy the Qin or a fine tea as much as any Chinese scholar or emperor. Tea binds us all, and I imagine that Emperor Huizong's spirit is thrilled to be a member of this Global Tea Hut!