|

|

To explore Taiwanese tea further than we ever have before, we needed a very special tea along the way - something worth stopping for, even amongst the gloriously lush mountains of Taiwan. We've sent out some great Taiwanese oolong teas over the years. Some were special because of the work of the farmer who produced them, like Mr. Xie's Three Daughters or the GABA tea we sent one autumn; others were as rich in history as they were in ecology, like the Old Man Dong Ding Master Tsai donated or the special roasted Buddha's Palm Master Lu donated. This month's tea is another gem in the Global Tea Hut oolong crown: an eco-conscious, traditionally processed Li Shan oolong roasted by one of the most famous and best tea roasters in Taiwan's rich tea history. As you can see, this tea has a lot going for it!

We send out a lot of magical teas, and so many of them have been stunners. This month's tea ranks amongst the best of them - right at the very peak of all Global Tea Hut teas! And the three characteristics that make it an exceptional Taiwanese oolong all invite further discussion and learning together: it's sustainably grown, traditionally processed and master-roasted by one of Taiwan's best and most famous roasters, Tsai Ming Xun.

We talk a lot about sustainability around here, but it is a topic worth discussing, and over again. In the Treatise on Tea written by Emperor Huizong, which we translated in April, he says that the arts, including tea, are all flourishing because of a time of peace and prosperity. This suggests that tea is, indeed a luxury, even when used medicinally or as a part of one's spiritual cultivation. And if there ever was a time we could afford luxuries that come at the expense of Nature (a big "if "), now is not that time. It is important that we have more discussions about environmental sustainability and the importance of how the things we make affect the world we are a part of. And as the second-most-consumed substance on Earth, Tea has an important voice in such councils.

There are nuances, but mostly the problems are obvious: feeling separate from our environment and Nature (a kind of spiritual illness in itself ), humans have misunderstood the very real connection between the health of our environment and our selves. You can't have a healthy organism in an unhealthy environment. Even if agrochemicals can be shown to have minimal effects on humans, which is doubtful, especially in the long term, they are definitely not healthy for the ecology surrounding the cleared area where monoculture is occurring, and that negative impact will eventually influence humanity. If we had to make such a sacrifice in the name of survival, for medicine that could save or ease the suffering of many, for example, then it might be worth weighing the benefits versus the longterm consequences of such so-called "conventional farming" (we think the way plants have grown, naturally from the ground for millions of years, should be the real "conventional;" it's strange that such unhealthy practices have become so ingrained as to be "conventional"). Risking the health of the world and people to make sure everyone has enough food might be worth discussing (might), though the lack of sustainability in such farming makes the environmental view seem to be the clear and obvious choice. However, harming the environment and risking your own and other people's health over a luxury like tea seems absurd.

And if tea is less of a beverage/luxury to you and more of an aspect of self-cultivation or Dao, then the need for the tea to be clean and grown in a way that does not harm the Earth, farmers or those with whom you share it is even more essential. Our tea should give, not take from the world.

Most of us trying to cultivate ourselves realize that our conduct will form the basis of our practice and also help us gauge the results. When we start cultivating the qualities of our highest self, a compass of compassion starts forming and our conduct in speech, action and thought starts being oriented in the direction of loving-kindness. Our ability to live from that orientation, along with our mistakes when we don't, will be our guide in knowing how our practice is going. But these days, understanding the effects of one's choices is more difficult, as the globe becomes more connected. We have what some Zen masters call "ghost karmas." Ghost karmas are the results we can't see, as they happen too subtly or too far away. Nowadays, our choices can impact the lives of people very far away, like which tea we choose, for example. For that reason, it is essential that we purchase and then prepare tea skillfully.

If our aim is to find peace and connection to Nature through our tea practice, then we will be frustrated by conventional tea. How could we claim that the Center is a place of peace if the whole place orbits a tea practice that is built upon tea produced in a way that is violent to Nature? What would connection to Nature look like if the vehicle of that connection is offensive to Nature? In trying to create peace or harmony with the natural world, we must use tea that is grown in a way consistent with this goal. Also, the way the tea is grown and processed, including the motivation behind it, will determine its ability to bring such harmony into our lives. Harmony starts on the farm. We've all tasted the difference between a store-bought, "conventional" tomato and one grown in a garden by someone who loves gardening. The latter is better in every way: flavor, aroma and the way it feels in our bodies. Even as hospitality, interest or hobby, tea that harms Nature and the lives of others is unlikely to result in connection between hearts, especially since it is a sense of distance and separation that causes many people to ignore the effects their purchasing decisions have on the ecology in Asia, as well as on the health and lives of local people.

Complaining about problems, agricultural or otherwise, is not the Global Tea Hut way. We'd rather discuss the solutions, or at least talk about the problems in light of change. There are four ways that we tea lovers can make a change in the world of tea, and perhaps in our relationship to Nature in general: choose only sustainable tea (obviously), use less tea, take care of the farmers and educate others. Each of these is worth discussing briefly as part of the eco-consciousness of our Tea of the Month, before we turn to the traditional processing and roasting by Tsai Ming Xun.

Choosing sustainable farming is the easiest and most obvious of the ways we can help. Don't let vendors convince you that this doesn't matter. It does. Most farmers are trying to make a living, and the larger and more influential the eco-centric tea market is, the more people will make the switch. Why wouldn't they choose to grow tea in a way that is healthier for their land, their families and their customers? The only reason not to is if it is challenging to make a living doing so, or if they can earn more by increasing their production through agro-chemicals. By creating a greater demand for sustainable, clean tea and putting pressure on tea merchants to carry such teas, we can all create a market that encourages more and more farmers to make the change.

The second way we can help comes out of the first, though it may seem more philosophical and less practical. The fact is that we cannot move forward by exclusion. We have to include, remembering that farmers are the first victims of this kind of agriculture. They are the ones exposed to the chemicals in their strongest form, and often the first to suffer pesticide poisoning or cancer due to exposure. We cannot ask farmers around the world to take care of the environment if they are not cared for. Due to centuries of feudalism, farming has become an undesirable career, without thanks or respect. However, we all need to remember that no matter what we do - doctor, lawyer or musician - we do it because of farmers. If we had to find/create all our own food, we'd have time for nothing else. Actually, farming should be the most respected career, as it supports and facilitates all careers. When farmers are cared for and their families have no financial needs, when they are respected and honored for their contributions to society - only then do we have the right to ask them to care for their earth. If farmers are struggling to make ends meet, discussing environmental issues is moot. This is why it is important for our tea to be fair trade, supporting and contributing to the lives of the farmers who create our precious leaves.

Tea merchants often promote tea, tea brewing methodology or even teaware that increases how much tea we use. Obviously, they want us to consume more. But the fact is that properly grown and prepared tea is very patient and a very small amount can satisfy you for a whole day. Just like food, if tea is grown and processed properly and with care and then prepared in like fashion, we don't need so much to stay healthy. A little tea medicine is enough for a day, just like a few vegetables grown properly and sustainably in nutrient-dense environments will satisfy most of our nutritional needs. Using less tea is probably the most significant thing a tea lover can do to influence tea's overall environmental impact. This means less each session and less throughout the month as well. When the tea is fine, and prepared properly, we don't need much. This is a good reason to cultivate one's brewing skills as well.

Finally, it is important for us all to spread this message to let more tea lovers know that their approach matters and that they can make a difference to the Earth, to the lives of farmers and even on agriculture itself! Recently, we went into a tea shop in the United States and our friend asked the clerk if their matcha was organic. The young woman answered the way she'd been trained to: ignorantly. She said, "No, but that is a good thing. Tea doesn't taste nice when it is organic." Though this was sad to hear, it was also a call to action. Education is needed, and it should be free of endorsement. They need a Global Tea Hut subscription at that shop!

Our Tea of the Month comes from one of a small, rare but growing kind of sustainable, natural tea farm in central Taiwan. Finding high-mountain oolong from places like Li Shan that is grown sustainably is still rare, but more and more such farms surface. There was a time when we rarely - if ever - drank Taiwanese oolong tea. There was low-elevation tea, like the wonderful tea produced by Mr. Xie, and some farms in Sun Moon Lake were making red tea, as well as several farms in Pinglin that were making Baozhong tea, but finding clean tea from the central mountains was nigh impossible. The reason other regions had more sustainable tea is that such tea isn't as popular in the central highlands. The value and reputation of "high-mountain oolong" made large-plantation conventional farms too profitable for farmers to think about changing. The trend towards sustainable tea began because of a growing environmental awareness in Taiwan in general and also because lower-altitude regions, like Dong Ding, began using eco-conscious farming as a way to distinguish themselves and compete with higher-elevation farms. Nowadays, some farms are starting to make the switch and you can find the rare Ali Shan or Li Shan tea that was grown sustainably, like our beautiful Tea of the Month.

To understand why traditional processing is rare, we have to once again review a short history of Taiwanese tea. There is a growing trend of traditionally processed oolong, which in some ways follows the organic trend - in that it also began as a way for lower-elevation regions like Dong Ding to compete in a market that was leaving them behind as well as in response to organic farming methods. This is because organic tea responds much, much better to traditional processing since the leaves are often bug-bitten and therefore oxidize differently than whole leaves that were protected by pesticides. Before we discuss the history of oolong in Taiwan, we should first explain what traditional processing is.

Oolong is a semi-oxidized tea. Don't be misled by this statement and start thinking that "all tea is Camellia sinensis and the difference is in the processing," as many authors would have you believe. We have been over this before: different processing techniques evolved over time to suit different varietals of tea. Farmers developed their processing skills to bring the best out of the local varietal(s) they worked with. Such improvements happened through innovation, insight and some trial and error. And while you can process a region's varietal(s) using the methods of another place, it won't be the same. And any tea lover will be able to tell the difference. That said, oolong tea is semi-oxidized and traditionally the range of semi-oxidation was much narrower. As we will discuss shortly, the range of semi-oxidation is much greater nowadays, so saying an oolong is "traditionally processed" means it falls into that narrower, higher range of oxidation, as oolong was processed for hundreds of years until the 1970s-80s. Simply put, traditionally processed oolong means higher oxidation and roast.

Oolong tea began some time in the early Qing Dynasty (16441911). It is withered indoors and out, shaken, fired (sha qing), rolled and roasted. It is the shaking that really distinguishes oolong from other kinds of tea. (We'll discuss this in greater detail later.) This kind of processing went on relatively unchanged, with minor improvements, until modern times. It wasn't until Taiwan began modernizing that things began to change, influencing the entire tea world in many and varied ways.

In the 1970s, everything was "Made in Taiwan" the way it is all from China today. This industrialization brought prosperity to Taiwan. As Emperor Huizong said in the Treatise on Tea we published in April, it is only when the land is prosperous and peaceful that people can pursue art and culture like tea. And as the Taiwanese economy started expanding, and food, shelter and life were all abundant, the people started refining and exploring their rich Chinese heritage and culture, including, of course, tea, teaware, brewing methodology, etc. There was a boom in tea culture, as demand went through the roof. Small, aboriginal tea farms slowly started changing into large plantations, owned by the families themselves or sold to larger corporations. This demand for greater quantities of tea drove oolong production into previously uncharted territory, creating new obstacles and challenges along the way.

Traditional oolong processing is the most complicated and skilled of all tea production. This is not to say that it takes little skill to make a fine green tea, for example. It takes a great deal of skill, in fact. But traditional oolong is more complicated and delicate and there's a narrower margin of error - misprocessed leaves are rigorously down-sorted (even more so in less-profitable yesteryears). It takes decades to master. In fact, it will be decades before a son is allowed to supervise an entire production with confidence. And one thing we all love about tea is that it comes to us as an unfinished leaf. So much of the quality is changed with brewing skills, in other words. Those of you with experience brewing traditionally processed oolong will know just how finicky, sensitive and ultimately unforgiving it can be. It requires the most skill (gongfu) to prepare well, and sometimes preparing it well makes all the difference between a glorious and sour cup! The fact that the processing takes decades to master and requires great skill, has a tight margin of error and requires brewing skills to make a fine cup was hardly compatible with the increased mainstream demand for tea that occurred at the time. Farmers needed tea production that was mechanized and easy to master, allowing employees to be trained in a matter of weeks; they needed a wide margin of error so that slightly misprocessed leaves would go unnoticed; and they needed the tea to be easy to prepare so that consumers could put it in a thermos, a tea bag, a mug or a pot and it would turn out fine. They needed lightly oxidized oolong.

Light oxidation and little to no roasting produces a greener kind of oolong that is easier to make, has a wider margin of error and can be brewed any way you like, maintaining a bright, flowery fragrance that appeals to the mainstream. This shift in tea production later moved to the mainland as well. This changed the tea world, including teaware, tea brewing and even puerh production and scholarship. As a result of these changes, Taiwanese tea lovers began switching to puerh because they didn't like the domestic transition to lighter oolong. And their interest reinvigorated a deteriorating puerh culture, sowing the field that would grow into the vast garden of puerh we enjoy today.

While lightly oxidized oolong can be wonderful, it is often very fragrant without much body. It is also rarely produced in a healthy, sustainable way that is good for the Earth. Most of the time, it is more like a tasty appetizer than a good meal. You may have prepared a lightly oxidized oolong for guests and then looked around afterwards, wondering what tea to drink. Tea lovers are rarely satisfied by such a tea, in other words. (That also suits the producers, of course, since we then drink more tea.) There are exceptions to this, but usually traditionally processed oolong tea is richer, more full-bodied and satisfying to drink. There's a reason that farmers adapted their processing the way they did: to bring out the best in oolong varietals. There's also a reason why it went relatively unchanged for centuries. Creating lightly oxidized oolong did breathe some fresh air into the oolong world, resulting in many new innovations and some wonderful new teas, but for a while, the new swallowed the traditional whole.

Due to marketing, the mainstream started somewhat mistakenly regarding altitude as equivalent to quality, and lower-altitude farms lost a lot of patronage. Some of these farms switched to organic and/or traditional processing to make themselves stand out from greener high-mountain oolong tea. As a result, traditional processing has once again become popular in Taiwan, which is a great thing for those of us who appreciate it more. No matter how you feel about lightly oxidized oolong, it is nice to have both. We just hope that more of the greener oolong producers will start making the switch to Earth-friendly agriculture, as it is definitely not a genre known for clean tea (which is, of course, another reason we don't drink much of it at the Center).

Though lower-altitude regions like Dong Ding have begun processing oolong with more oxidation and roast to stand out, and that has meant that some higher farms have also made limited amounts of traditional tea, it is still rare to find tea from higher altitudes that has been traditionally processed. Usually, when this does happen, it is because a shop owner has ordered such rough tea (maocha) because he wants to roast it himself, like our Tea of the Month. And, we should remember, even so-called "traditionally-processed" oolong in Taiwan nowadays is nowhere near as oxidized nor as roasted as tea was before the 1970s.

Our Tea of the Month is very unique for being an eco-conscious high-mountain oolong, but also for being traditionally processed. Hopefully, you can taste how clean this tea is and why traditional processing suits oolong tea, especially when it is clean. You almost have to process such tea with more oxidation and roast, since the leaves are often bug-bitten.

In traditional oolong processing, there is no stage more important than the roasting. The roast is what brings out the best flavor in the tea and it requires a high degree of skill. The master must understand each batch of tea and adjust the duration and temperature very subtly to roast (and often re-roast) the tea to perfection. Master roasting is hard to come by these days, which is another reason that many farmers turned to lightly oxidized, greener oolong. To complete the hat trick of sustainably grown and then traditionally processed oolong, our tea was superbly and skillfully dried and roasted by Mr. Tsai Ming Xun, a true legend in the oolong roasting world.

Tsai Ming Xun doesn't come from generations of tea processing, but he has started a legacy of his own. He was born in 1963 in Zhiayi, Taiwan. At a very young age, he fell in love with all things tea, teaware and antiques, saying, "I only loved the household items: the things that have really and truly been used." He opened a teahouse in 1985 at the age of twenty-two. He had gone down to Tainan for school and so chose that for the location of his tea house. In those days, tea and all things cultural were booming and the teahouse thrived.

After ten years, the tea house craze in Taiwan started declining and the entire tea market was subsiding. Mr. Tsai carried on for another five years before making a decision to convert the teahouse into a shop and just sell tea for a living. He has carried on selling tea at the same location until now, making his tea spot more than thirty years old.

After the severe earthquake of 1999, much of central Taiwan was destroyed. Many tea areas were negatively impacted, and tea lovers of all kinds pitched in to help out in different ways. In a previous issue, we talked about how teaware makers like Deng Ding Sou gave free lessons to affected farmers to start them on a different career path. At that time, Mr. Tsai bought up three small tea farms to help give those families a chance to start over in the city. He worked together with other locals, but says that he gave up on that after a few years. "At that time, and sometimes still today, local farmers have a very different view of tea than us. They just see it as a cash crop, not knowing how much passion and culture there is in tea. They don't love it the way we do." For that reason, he started out making tea himself with the help of some employees he hired to help him maintain the gardens and to harvest when the time came.

As we have often discussed, tea production was different back in the day. Tea houses and shops would buy rough tea (maocha) from farmers and then roast it to suit their customers' needs. Mr. Tsai roasted all the tea for his teahouse and then shop for many years and developed a reputation as one of the best tea roasters in Taiwan, winning competitions along the way. He told us that if you had asked him then, he would have said that roasting was the most important part of making fine oolong tea. But these days he feels otherwise: "Now that I have gone deeper into tea production and have my own gardens, I actually feel that it is just the opposite - roasting is the last, and therefore least important stage." He says that each step is more important than the next, so the terroir and garden (location) are the most influential factor in tea quality. "This is because each step determines what follows: the location/terroir will determine the best varietal of tea to plant. The varietal and weather of that season/place will then determine the harvest, which will determine the processing, and so on." When we asked him how he became known as a master roaster, he said, "I think one reason I was so good at roasting tea back in the day is that I had a unique palate and knew how to choose tea that would suit my style of roasting. Looking back, I realize that I would turn down lots of maocha, saying, 'I don't want to roast that, but I do want to roast that.' This selection of the right tea is where more of the quality of a fine tea lies."

Mr. Tsai doesn't call his tea production "traditional," though he doesn't mind the term. He says that he thinks his tea is a synthesis of modern and traditional, since tea lovers and producers nowadays have a background in scientific research that traditional farmers didn't have, and they therefore understand the chemistry and soil in ways that are very modern. He hopes to combine modern understanding with traditional skills, in other words.

Tea back in the day was made on very small farms and processed in simple rooms that were part of the farmers' homes. There weren't any factories or processing facilities like today. He says that the demand and market have, of course, negatively influenced Taiwanese tea quality. “Nowadays, a lot of tea makes you uncomfortable. Farmers can’t wait for the right weather to pick or process the tea—not when their customer is anxiously waiting for their tea. They have to pick, even if it isn’t ready or if the weather is not conducive to tea picking. And it takes a lot of skill to overcome those kinds of challenges.” Mr. Tsai told us that his movement towards heavier oxidation and roast came because a lot of his customers, in China and Taiwan, are Buddhists and therefore vegetarian. “They are, therefore, even more sensitive to teas that make you uncomfortable.” A lot of lightly oxidized, green oolongs are more astringent and less desirable to vegetarians.

We find a place comfortable due to just a few factors, like that the weather is pleasant and the surroundings lovely. But trees are tuned into the minerals in the soil, microbial life and many other subtle influences we can't even begin to notice.

Along the way, making more oxidized and roasted tea, he also found that the lighter teas were fragrant, but lacked body. And they often leave the drinker uncomfortable. He said that many modern tea lovers do not want to learn all the details of the complicated tea world or understand the history, chemistry and all that goes in to tea. "They just want a tea that they can drink and feel comfortable, relaxed and bright - a tea that is delicious, fragrant and healthy." Added pressure from advertisements and dishonest merchants using stories to sell low-quality tea has also left a lot of customers jaded. Mr. Tsai said something akin to what Master Lin always says: "Without the need for words, they drink the tea and find its quality there." Master Lin's version is: "The truth is in the cup; tasting is believing." Mr. Tsai went on to discuss the antagonism between lightly oxidized tea and natural, more sustainable tea production. He said that in order to make such fragrant, green tea in large quantities it is necessary to protect the tea leaves from insects, as their bites would begin oxidation and make such tea production impossible. Therefore, higher oxidation and roast were traditionally suitable to tea production, as there was no way to keep insects away completely. It would require a lot of skill to process a tea well and keep it very fragrant and lightly oxidized if bugs had bitten the leaves. This means that this lighter-oxidized tea industry will never really be conducive to sustainability. "The market will have to decide if it wants such fragrant tea or if it wants environmentally conscious tea," Mr. Tsai said.

Mr. Tsai concluded by telling us that trees are much more sensitive than people. "We find a place comfortable due to just a few factors, like that the weather is pleasant and the surroundings lovely. But trees are tuned into the minerals in the soil, microbial life and many other subtle influences we can't even begin to notice." He said that to master tea processing, one has to get in touch with as many of these subtle forces as possible - to study history and tradition, learning and honing one's skill, as well as modern science, which has revealed the workings of many of these subtle factors to us. In understanding one's tea, the master can adapt his processing to suit the tea and bring out its best quality. "A fine tea should be smooth and delicious and leave you feeling comfortable. If you drink a tea and feel uncomfortable in any way, that isn't the tea for you."

Our Tea of the Month was dried and roasted by Mr. Tsai quite skillfully indeed. The higher oxidation and roast bring out a nutty apricot flavor that is divine. They say that each stage in the tea processing should enhance the tea without leaving a trace of itself, so the roasting should not leave a roasty flavor, in other words. This tea is roasted superbly, with a strong and bright aftertaste that lingers in the mouth for many minutes after you swallow. We find the energy of Nostalgia to be uplifting, gentle and calming, even though it is quite yang. It fills you and carries you upward, but not forcefully. It is gentle, like a well-mannered lady of the Qing Dynasty. She plays you a guqin recital, comments on the sutras and makes you feel humbled by her magnificence.

Drinking such amazing oolong always helps demonstrate the power of human and Nature working together in harmony. The powerful terroir of the highlands of Taiwan combined with master craftsmanship results in something that transcends the world of human or Nature. In some ways, this is a metaphor for what it means to be human in this world, and certainly for everything great tea is about: Heaven, Earth and Human working together to co-create transcendence. See if you can taste the rocky, high-altitude grace of Nostalgia, as well as the superb skill of Mr. Tsai Ming Xun; and then see if, cup by cup, you and your guests don't start to taste what's beyond...

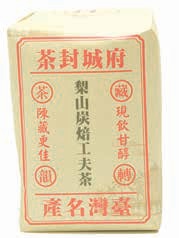

Though we can't send you all a 150-gram package of this month's tea, we can show it to you and celebrate that Mr. Tsai took the time to package this tea traditionally, just as it was processed. Because of the higher oxidation and roast, traditional oolong didn't need to be vacuum-sealed (a method that creates a lot of waste). It was wrapped in paper and would only get better with time. The paper let the tea age properly and was convenient for folding up and refolding the tea after each use. Watching old tea vendors quickly fold up 150-gram packages of tea is something every tea lover should witness! They deftly fly through the many folds, which result in a rectangular paper box that fits perfectly around the tea. It goes without saying that tea drinkers back then would have known how to refold their packages, though with less speed or skill than the shopkeeper.

Our Tea of the Month was wrapped by hand in a cool vintage paper with prints of traditional "Formosa" tea ads and a description of traditional processing. The vintage-style wrapping and print add nostalgia to the tea. Most of the time, packaging says little about a tea, and the more well-packaged it is, the lower the quality tends to be. As in all stages of tea processing, anything that stands out is probably distracting from or covering up a fault. But this is the exception, as the love and extra care it took to hand-wrap this tea is a testament to the way it was produced.

Like so many of you, we also sit down with friends to share the Tea of the Month. And though we drank Nostalgia at a different time than you, we are reminded once again of the interconnectedness we share within this global tea community. Just as we set out altar cups in acknowledgment of our tea brothers and sisters the world over, we also drank this tea with all of you in mind, knowing that somewhere under this global thatched roof, you'll likely be doing the same! And just as you might discuss your experiences drinking this tea with your friends, we did the same:

Like a summer rain, She puzzles me. Slowly, drop by drop, this tea drenches the inside of my mind and tempers my spirit. Her wild travels are, nevertheless, incorporeal.

Lush moist green landscapes, subtle aromas of honey and spring, a perfect nutty roast. This tea challenges my breath and lifts my spirit from the mouth to my upper nostrils, swirling inside the cavities of my head and warming my whole body. A gentle and powerful Qi. I feel it is perfectly balanced.

When I sipped the second cup, there were hints of cocoa that transported me into the lush Guinea plantations, together with an aftertaste of freshly cut leaves. The fifth cup awakened the roasted and honey tones that I smelled in the dry leaves prior to brewing and relaxed my mind into a gentle, meditative state.

Perhaps the name "Nostalgia" refers to a time when oolong was traditionally processed, but I'd like to think it refers to the dreamy quality of this tea, drawing us into pleasant memories. This oolong is beautifully balanced, filling the entire mouth with strong flavors of fresh grass and flowers. The long aftertaste lingers between cups, creating a bridge so that the state of being elicited by the tea expands throughout the session. The brew is clear and oily, leaving the mouth salivating.

From the very first cup, Nostalgia splashed up to my upper palate, centered my mind and gently warmed my body. These sensations unearthed a vision of a log cabin tucked away in the woods. It was a very full and abundant tea, as self-sustained as that cabin. It required little, but to sit and let cup after cup come to me. I didn't need to concentrate on it in order to understand it.

Because of the great skill that goes into the production of oolong tea, it has always been more expensive. In the south of China, a new method of tea brewing developed along with oolong, called "gongfu tea." Gongfu tea brewing was created by martial artists, and was therefore inspired by much of the same Daoist philosophy that informed those practices. By brewing the tea in small pots, with small cups, these masters simultaneously preserved this valuable tea and cultivated skills and refinement, grace and fluidity in concordance with their worldview.

If possible, we would always recommend brewing an oolong like this gongfu: with an Yixing pot, porcelain cups, a tea boat and kettle/stove. If that isn't possible, you can adapt this tea to any method of brewing or pot/cup/bowls that you have. Don't feel like you have to brew this tea gongfu or not at all.

A general rule for brewing oolong tea is to cover the bottom of the pot like the first, freshly-fallen leaves of autumn: covering the bottom, but you can still see it. This is important because ballshaped oolong teas really open up a lot, and they therefore need the room to do so. Remember, it is always better to start with too little and add more than to use too much, which wastes tea. Give the tea a longer rinse, so that the balls can open a bit more before pouring. This helps ensure they won't get bunched up near the spout before they are fully open. The ideal is to get all the balls to open equally and at the same time, which will produce an ethereal third through fifth steeping!