|

|

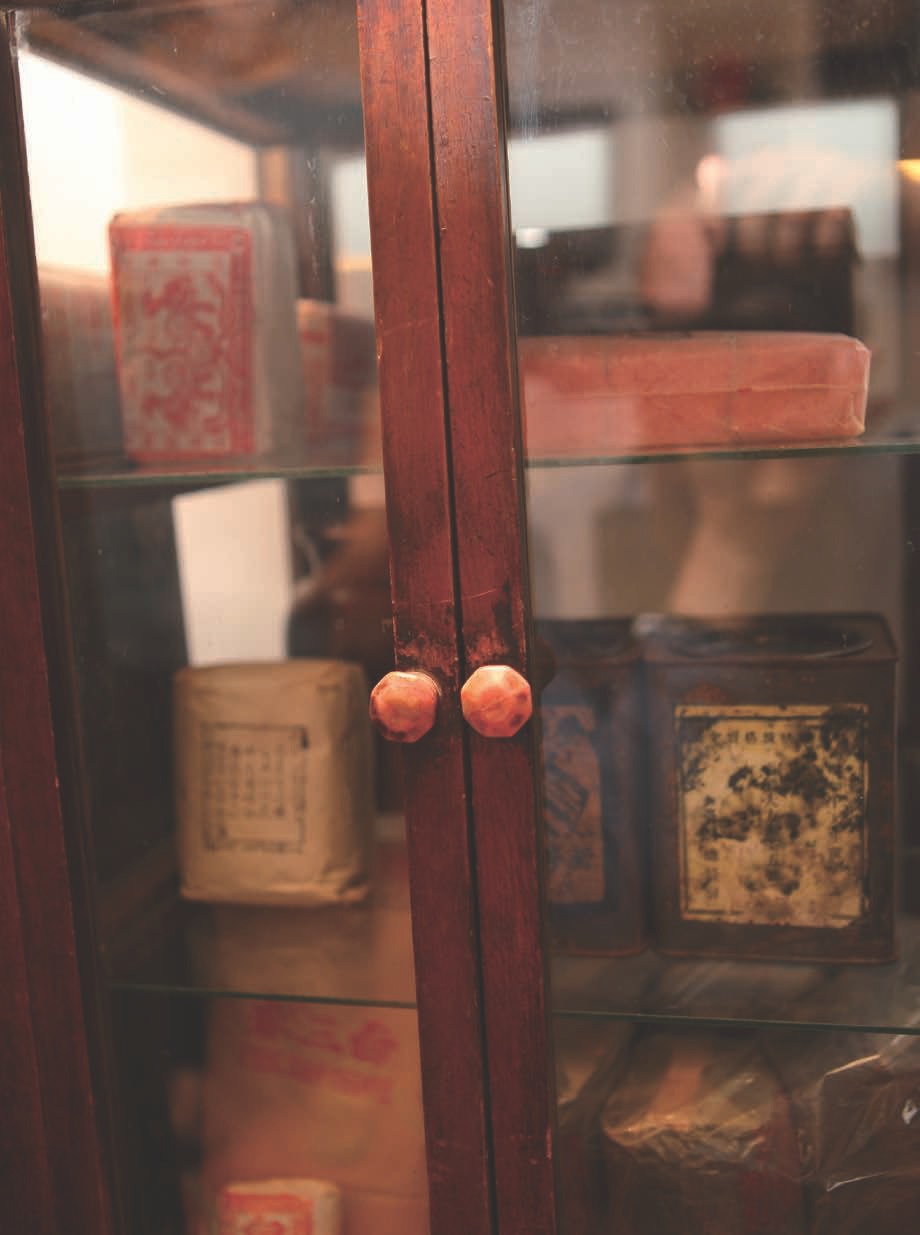

Imagine yourself savoring a cup of aged Wen Shan Baozhong tea from 1979. The tea leaves have witnessed the passage of more than thirty years to bring you this sweet, mellow tea liquor with its warm, clean fragrance. As you breathe in, your nostrils are filled with the scent of tea, soothing away life's stresses and anxieties. Our search for this traditional Taiwanese oolong flavor brought us to the Yeh Tang Tea Culture Research Institute on Taipei's Yongkang Street, where we listened attentively over the teacups to veteran tea master He Jian as he tirelessly recounted the stories behind Taiwan's traditional oolong tea varieties: Wen Shan Baozhong, Muzha Tieguanyin, Dong Ding oolong, and Eastern Beauty. His passion was contagious, and we fell in love with tea again. Master He's tea and stories did more than inform us; they left us inspired. Through his words, we were carried along on a journey through time, following the rise and fall of that traditional oolong flavor, in pursuit of a fragrant curl of steam that wafted, dreamlike, through history.

Wen Shan is situated in the southern and south-eastern regions of the Taipei Basin and was Taiwan's earliest tea-growing area, with tea first being cultivated there in 1810. Wen Shan Baozhong tea originated in Taipei's Nangang district in the late 19th century. Its founding fathers were two natives of Anxi County in Fujian Province, Wang Shuijin (王水錦) and Wei Jingshi (魏靜時) who immigrated to Taiwan. They established a tea plantation on a hillside of Neihu Village in the Qixing region (near the old Nangang Village), and started to produce tea. From that point on, two distinct styles of Baozhong tea gradually developed: Wen Shan style and Nangang style, each very different from the other.

Of the two tea growers, Wang Shuijin represented the Wen Shan Baozhong tea-making method, using a technique borrowed from Wuyi tea that involves twisting the tea leaves. With the existing Wuyi method as a starting point, he developed a process with a more thorough oxidation and roast, resulting in a stronger fragrance and a deeper, reddish-colored liquor. Because of its distinctive flavor, some people are still quite enamored of this stronger-scented, Wen Shanstyle Baozhong tea. Wei Jingshi, on the other hand, modified the Wuyi tea-making method used for the Wen Shan style, changing the whole process right from the withering stage to produce a more lightly oxidized tea with a greener liquor and a lighter, sweeter fragrance. This was the Nangang style of Baozhong tea - the predecessor of the Wen Shan Baozhong tea that is commonly seen today.

The term "red water" (referring to the color of the liquor) that dates back to the period of Japanese occupation was in fact used to distinguish the Wen Shan style from the Nangang style of processing. In 1921, the Baozhong Tea Institute was established in Nangang to promote tea production and pass on knowledge of tea-growing and manufacturing techniques to the local tea farmers. At that time, the bulk of the tea leaves were exported, together with those produced in the neighboring areas of Pinglin, San Xia, and Da Dao Cheng, with whom Nangang enjoyed close and mutually beneficial business ties. Later on, due to several factors such as mining and urban development, tea production in the mountains of Nangang slowly began to decline. The center of Nangang Baozhong tea production gradually began to shift toward Pinglin, where the environment was more favorable. From 1975 onward, the tea market gradually became geared toward domestic consumption, and these two villages that had sprung up because of the tea industry - Nangang and Da Dao Cheng - slowly went into decline.

Baozhong tea has a light, elegant flavor and a distinct fragrance, and is well-regarded in the market. Furthermore, the price of Baozhong tea is completely determined by the quality of the tea itself. The difference is obvious, unlike tea leaves from most tea regions where the price is relatively uniform and there's no way to distinguish the quality. In my opinion, Baozhong tea's distinctive flavor makes it the most classic example of Taiwanese tea, and one of the best teas to represent the small and refined character of Taiwan.

During the period of Japanese rule, tea masters Zhang Naimiao (張迺妙) and Zhang Naigan (張迺 乾) imported Tieguanyin tea seedlings from Anxi and planted them on Zhanghu Mountain in Muzha District (also called "Mucha"). Due to the favorable soil quality and climate, the area of the plantation expanded rapidly and Muzha became a Tieguanyin growing region. The main features of the manufacturing process included using leaves from the original Tieguanyin bush varietal, followed by relatively heavy oxidation, repeated cloth-rolling, and hand-roasting. This created a unique flavor with a rich, strong fragrance and a hint of tart fruitiness, and led Tieguanyin to become famed as a regional specialty tea that's representative of the traditional art of Taiwanese tea-making.

In recent years, the characteristics of Tieguanyin, from the aroma to the mouthfeel, have all changed a lot from that early style. So what were the main factors that contributed to the evolution of Tieguanyin's flavor? The external factors include the development of tea plantations in Maokong in the 1990s that were aimed at sightseers. After Maokong became a tourist attraction, many businesses sprung up in the area, and the influx of labor and resources changed the face of the local industry, causing the tea industry to decline. The main internal factor, on the other hand, was that as farmland was passed down through generations of tea growers, it was continually redistributed and divided into smaller and smaller sections, dramatically decreasing the area available for planting. Because of these core external and internal influences, it was inevitable that Tieguanyin would undergo a fundamental change.

In addition, the advent of tea competitions had an influence on the flavor of Tieguanyin. The authorities hoped to stimulate the tea economy, so from their perspective, the more tea varieties entered in the competitions, the better. In order to keep the competitions running, they needed to expand the area of origin of the raw tea leaves, so tea growers moved to Pinglin to grow their tea, and started to make Tieguanyin using tea leaves from the Pinglin region. Tieguanyin teas from areas of mainland China also entered the arena alongside Muzha Tieguanyin, slowly diluting the distinctive traditional flavor of Tieguanyin.

I believe that the rarer the production of traditional Tieguanyin becomes, the more we need to highlight the few remaining great tea artisans, tea bush varietals, and tea-making methods, to set a benchmark for the industry. I hope that this high benchmark will become the pride of Taiwan and set an example for Anxi, so that once it has gained prominence, its uniqueness will be better recognized. To truly capture the "Guanyin spirit" that is so sought-after in traditional Muzha Tieguanyin tea (named for Guanyin, the Bodhisattva of Mercy), you really need the genuine Tieguanyin varietal, plus the traditional manufacturing method. If we can promote the proper appreciation of Tieguanyin, then people will recognize its true rarity and worth and there will naturally be a market for it. Once demand is established, it will have a stimulating effect on the wider industry.

Eastern Beauty tea is also called "Peng Feng tea," or "Bai Hao (white tip) oolong." It's mainly produced in the Taoyuan, Hsinchu, and Miaoli areas of Taiwan. Its most recognizable characteristics are its delicate, lingering honey aroma, and the way it combines the traditional taste of oolong with the richness of red tea - of all the oolongs, it's the closest in flavor to red tea. In 20th-century England, Eastern Beauty's distinctive taste and vigorous, energizing liquor was received with great enthusiasm and became very popular.

Eastern Beauty can only be produced in one season of the year (global warming has caused the quantity they are able to produce in winter to diminish). This makes it very difficult for small-scale tea farmers to make a living from growing it, and the production of Eastern Beauty tea in Taiwan is gradually decreasing. The tea plantations are small and the resources concentrated, which makes it relatively easy to hand-select the choicest tea leaves that have been bitten by the small green leaf-hoppers whose saliva gives the tea its characteristic sweetness. Because of this, the same few people tend to take the top prizes in the tea competitions. Add to this the importing of teas from outside Taiwan (and other factors) and the result is that over time, this type of tea has also lost some of its unique characteristics. The level of oxidation has become lighter and lighter, and environmental changes have meant that the unique quality resulting from the green katydids' saliva is less and less prominent. The tea that is now produced can easily fetch ten to twenty thousand New Taiwanese Dollars per half a kilogram, yet the brewed tea is a very pale golden-yellow color and lacks the traditional amber color and robust flavor it had in the past. So the fundamental quality of the tea has slowly changed. How could we allow such a distinctive tea to simply disappear, being among Taiwan's most recognized specialty teas and an important Taiwanese export, with a flavor appreciated by even Queen Victoria of England? Though we may not have the opportunity to experience Eastern Beauty as it once was, we cannot lose sight of its worthiness of our appreciation.

Dong Ding oolong is produced in Lugu Township in Taiwan's Nantou County, at an elevation of 500 to 800 meters above sea level. It's quite heavily withered and oxidized and goes through several rounds of rolling in cloth bags to give the leaves their balllike shape (one of the traditional skills involved in making Dong Ding oolong is rolling the tea with one's feet). After that, it's slowly roasted over a charcoal fire to give the tea its characteristic rich, mellow fragrance. The craftsmanship involved in making the tea is very delicate and complex, representing the art of Taiwanese tea-making at its finest.

The Lugu Township Farmers' Collective that sprang up around Dong Ding oolong tea made a very significant contribution to the local industry: the volume of tea that they submitted to annual competitions represented two-thirds of the total volume of all entries. Every year, the volume of spring and winter tea samples that they submitted to the competitions totaled several thousand dian (a measure equal to 11 kilograms). This had a big influence on the tea industry and established Dong Ding oolong as the leading player in Taiwanese tea competitions and the most well-known and influential of Taiwan's traditional oolongs.

These days, a situation worth pondering is this: in the competition categories for such a large-scale tea as Dong Ding oolong, the majority of the best-performing teas are in fact made from raw tea leaves sourced from very high-elevation tea plantations and not from Dong Ding itself. Of course, this is because highly elevated plantations have particulary favorable growing conditions, so the tea they produce has a pleasantly soft, sweet taste. But because of this, the original purpose of holding a competition for local tea varieties - that is, to promote and bolster the local tea-growing regions - has been lost. To draw a comparison: in a sporting event, athletes should be judged by their skill on the sports field, and not forced to dress up and enter a beauty pageant instead! Although the high mountain teas are indeed very sweet and fragrant, Dong Ding has a richer, more full-bodied taste and deserves to shine on its own stage. When making tea, it's important to work with the natural character of the tea. Only then can you achieve the traditional local style and flavor that Dong Ding oolong should display.

I truly hope that the Dong Ding tea region will be able to slowly recover, and that after the ecosystem and soil have been sufficiently cultivated, it will once again look just as it used to. Unfortunately, though understandably, no-one is willing to reproduce that traditional flavor of days gone by because of the time and effort involved - the road to the past is a hard road to travel. Some time ago, I had the chance to go to the mountains and experience tea-making for myself. You couldn't even go to sleep at night because you had to get up every two or three hours to process the tea - it was very hard work! Throughout the tea-making process, every time you turn the tea leaves over, every time you gather them up and spread them out, you can feel the subtle changes in the tea - in its appearance and scent; it's a moving experience. How many tea lovers get to experience that these days? It's become very rare. Now you just put the leaves in a tea-turning machine that rolls them for you. Likewise, after washing machines were invented, you rarely see anyone hand-washing their clothes, and we all use electric rice cookers to make dinner - the taste of that crunchy rice you fondly remember eating from the bottom of the pan is now just a childhood memory. You can't go back. These days, tea lovers are even more sincere and profound in their interest, and more numerous than we were back then, but there are so many things that they have never had the chance to experience, and probably never will. It really is a great pity.

The most outstanding features of Taiwan are its beauty and small size. In the past, our greatest source of pride was the purity of Taiwanese tea: the entire process from production to export and local consumption, the development of tea from an everyday drink to one of life's most refined pleasures... every aspect of this development has been very complete, and has established a very high standard for tea in Taiwan.

Take the sudden rise of aged puerh, for example. Aged puerh tea had been around in Hong Kong for a very long time and was a dime a dozen there; however, once it reached the palates of the Taiwanese people and they recognized its excellent qualities, it soon became very valuable. Taiwan had a taste for puerh tea, Mainland China had the capital, and Hong Kong had the goods - so aged puerh really highlighted the characteristics of all three places and created a fully formed supply-and-demand relationship. When others provide a market, we need to establish the right standards for appreciating tea, instead of just blindly swaying with the market. Once we've really mastered this "small and beautiful" quality and established our authority in appreciating and critiquing tea, we'll have a much bigger platform to make our voices heard. This will bring about many positive changes and enable Taiwan's traditional oolong tea to forge its own path in the world.