|

|

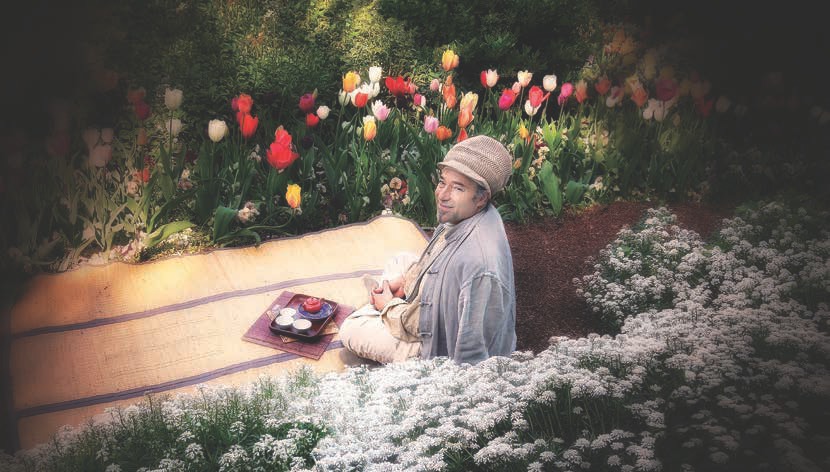

Sitting with tea has been a great gift to my life. Since the late 90's, my life as a professional musician has been filled with a constant stream of live performances and copious amounts of touring, both domestically and internationally. Tea has played a major role in this, especially during the busiest of tours, helping to keep me grounded and centered when out on the road.

As the tours would wind down and I was home more often, there were a couple of albums of music I played to accompany my daily tea and meditation practice. One day, after a session with a friend, she asked, "MJ, why don't you make an album of tea music?" It hadn't even dawned on me until just then. Here I was, a longtime professional musician, and I had never considered doing such a project, even though Tea is such a crucial element in my life. I thought: "Hmm, is it time for a new music genre called 'Tea Music'?"

Recently, in the summer of 2013, I graduated into fatherhood. I was suddenly faced with the myriad responsibilities that lay before me, and some spiritual housecleaning was automatically underway. Having children certainly creates immediate shifts, like a love tsunami washing away anything that doesn't serve the greater good.

As part of this, I saw the need to have my burgeoning tea life and my decades-long professional music career harmonize, and not compete for my time and focus - a trend that was occurring. Thus, with this confluence of energies all pointing in the same direction, the concept album Music for Tea was born, not even one week after our daughter was born.

And it truly is a "concept album." A whole vision emerged, based upon a cohesive through-line and simple, sparse approach of "one master, one instrument," with each weaving a part of a melodic story. Calling upon the talents of an array of master musicians, each playing a traditional stringed instrument in one long, live performance, I encouraged the artists to let the tone of their instrument resonate (quite a bit longer than they normally would) into the silent, open space around it. Drawing out each note, melodies would be played in a deliberately slower, unwinding way, framed by the void of the no-background-music supporting it. As the famous Jazz musician Miles Davis once said, "Music is the silence between the notes." In Music for Tea, that silence was meant to be heard.

I chose a variety of Pan-Asian stringed instruments that all had a common thread of that traditional sound. Due to decades of working across a wide spectrum of traditional World Music, I had long-established friendships with world-class master musicians from around the planet, a plethora of whom lived locally in Northern California. This was a project long waiting to happen, but somehow hidden from me like the tea bowl staring me right in the face.

Having spent some years working as a film score composer in Los Angeles, I was influenced towards creating a more visual thematic storyline to help guide the recording sessions. This would yield a highly focused end product and help create a common compositional sketch for the musical direction. Just as film score composers will custom fit music to some kind of visual action, I asked each of the musicians to imagine fitting their performance to a story, appearing below as it does on the CD case, in poetic verse:

Leaving home The Old Man, withered and weary Ascends the great mountain With difficulty, he makes his way Near the Summit, the ancient hut Welcomes him again A garden grown wild glows in the Sunset The Sacred Spring splashes out its 10,000 songs Preparing tea, he sits resolute A view of great expanse before him Eyes wide, piercing cloud and stone The answer comes without question Home now, is here.

The recording sessions were done one day at a time, with just one maestro and his or her instrument. Once we had established all the basic criteria for the musical direction, which certainly included serving them tea, I would tell them the story, and then the artist would play as though performing for a live audience, in one take. We typically did no more than three takes, to preserve the immediacy of the live performance energy, choosing the best for the final version. Throughout the sessions, puerh flowed like the river of sound echoing through the recordings. Tea was subtly steering the project, keeping us all on course.

Besides the storyline, there was a very basic sketch of composition to give the music a particular wave. Like brewing really good tea, each piece starts slow, building gradually to an energetic peak, then winds down towards the end.

The appearance on the album of world renowned sarod master Alam Khan - son of the late, great pioneering sarod master Ali Akbar Khan - was an incredible boon for the production, and the grace-filled finesse of his talent really shines brightly through his instrument; it yielded a stellar recording and became what I consider to be the energetic peak of the album. The piece is based on a traditional North Indian raga - a musical performance piece in a particular scale of notes, often assigned to a specific time of day, and with a specific mood. What is unique about this recording, is that although sarod is traditionally always accompanied by a drone instrument called "tanpura," I wanted more focus on the tone of the sarod, so I requested that Alam give it a go without the usual tanpura in the background. This may perhaps be the first-ever public release of such a highlevel master recording of solo sarod without tanpura behind it.

Gary Haggerty, a multi-instrumentalist also based in the San Francisco Bay Area, is a lead performer in the internationally-known band Stellamara. I wasn't sure Gary was going to be available for the project, but I had him high on the list of probable suspects for the job. Sitting with him in his home studio, with hundreds of stringed instruments of all kinds hanging on his walls, I felt his interest in the project pique. After recording the Robab track, which he nailed in the second take, he grabbed an unusual object. "This is a tarhu," he said, seeing my eyes get big like saucers. As he drew a bow across the strings of an instrument I'd never seen, nor heard (of ) before, the deep resonance echoed through his house. "Wow, okay. That's it. Let's get that one too," I said. Its low-end tones provided a nice contrast to the other strings on the album, and helped complete a whole color spectrum of sound. We finished recording both instruments so quickly - due to his immediate grasping of the project and incredible talent - that I almost forgot to drink tea. Almost!

As a surprise element to the album, a Pakistani vocalist named Aliya Rasheed was added near the end of production. Aliya had sung at a house concert in our area, and had completely won every heart in the room. I had no intention of having any voices on the project - until I heard her sing that evening. She was immediately open to the idea, and we arranged to have her record one song in a single-pass session. To have her bless this project was an unexpected treasure that really took the album to a whole other level. What's more, she's a woman singing a classical style of music called "Drupaad," which is a style of music very strictly sung by men for centuries! She is the first woman, and a true pioneer and women's rights leader in Pakistan, to publicly perform in this style and be a fully recognized artist in her own right. And if that wasn't enough, she has triumphed in the face of having no eyesight; she was born blind. I made certain that she was served a nice cup of tea before her recording. It seems to have done its job well.

The other instruments were recorded quite smoothly, thanks to my little portable studio. The only song I did not record originally is a song offered to the project by Wang Fei, a Bay Area guqin master. We had to have a traditional Chinese instrument on the album, and this piece worked wonderfully. It was used as a kind of introduction, at the front of the album, since tea culture spent much of its (ongoing) journey in ancient China. There were some odd airplane noises in the background of the original version, and the tone needed quite a bit of work, which we were able to solve in the mix sessions.

My travel tea set was getting well used during the production process. Each day of the very fast four-month production journey I used it to drink tea.

The mixing was a process of refining the sound quality of each song, smoothing the rough edges, removing any unwanted ambient noises, fixing any mistakes, and bringing out the rich tonality of the instruments. I mixed at a studio that happened to have an old Studer two-inch tape machine, a major collector's item in the world of professional recording engineers. This is what all the big record labels used back in the "old days." The analogue "tape sound" is highly coveted now and the magic of having the album run through a tape machine for the mix really added a velvety smooth warmth, expansive sweetness, and clear presence. (Sounds like Tea, doesn't it?)

It was also at this studio that I recorded the introduction "Bells" piece, using my entire Tibetan bell collection: a spontaneous recording inspired by thoughts of the so-called "Tea Horse Road," and fueled by some serious late night, dense steepings of aged puerh. My travel tea set was getting well used during the production process. Each day of the very fast four-month production journey, which was kind of a miracle for me (my previous album took nearly five years to complete!), I used it to drink tea.

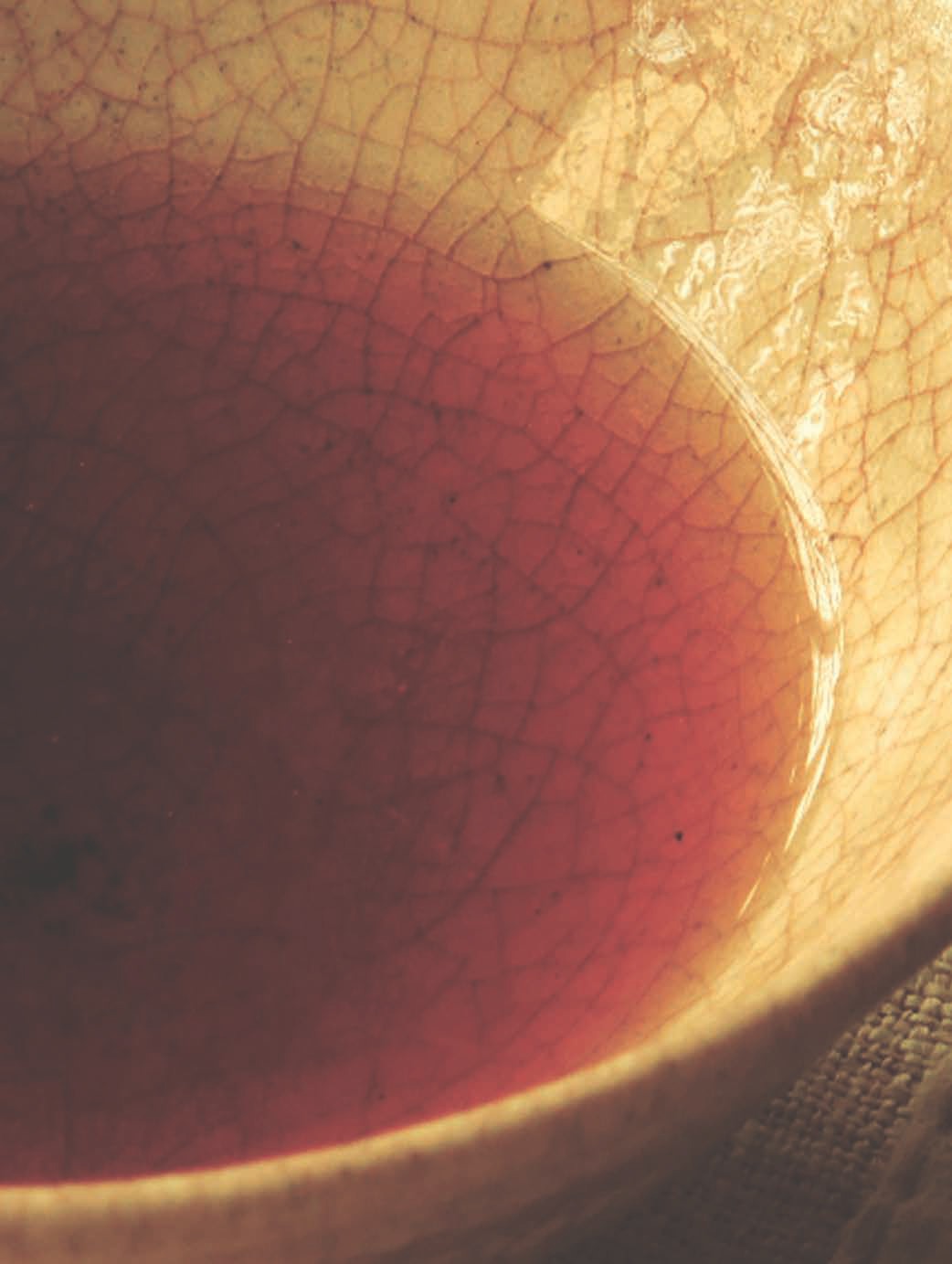

The mastering of an album is a type of equalizing all the songs so that they sound as if recorded in the same place. This also prepares the recording to be radio-ready. It's an extremely focused process of listening in a hyper-detailed way, literally focusing in on every single note, ensuring a pristine end product without any mistakes or glitches. At one point, I sat alone in the studio control room - a huge board of faders, knobs, and switches flanked by stacks of outboard gear - with the monitors (speakers) turned way up, holding my tea bowl gently as I was wrapped in a beautifully rich, warm silken blanket of sound. It was such a profound feeling: a very deep meditation lasting almost four hours. I emerged from that session in quite an altered state, floating out of the studio both tea and music drunk. That's when I realized: this is just the first in a series of Music for Tea albums.

The album's stringed instruments (except for the tarhu) are all traditional. The sarod, is from Northern India. The oud is found throughout North Africa, and the Middle East. The robab is from Afghanistan (it's the ancestor of the sarod, actually). The kora is West African, and the setar is a Persian traditional lute. To have this collection of sounds on one album is a real treat.

Little did I know that this album would end up being played in a tea center all the way over in Taiwan. I am grateful that this music has already found so many kindred tea spirits. Like birthing a child, Music for Tea has taken on a life of its own and is doing whatever it needs to do out in the Tea-niverse. It feels like it's barely started its journey. Who knows just where it will end up or how it will fulfill its greater purpose? Oh, the wondrous mysteries of Tea! Many thanks to the Global Tea Hut family for supporting tea music and musicians!