|

|

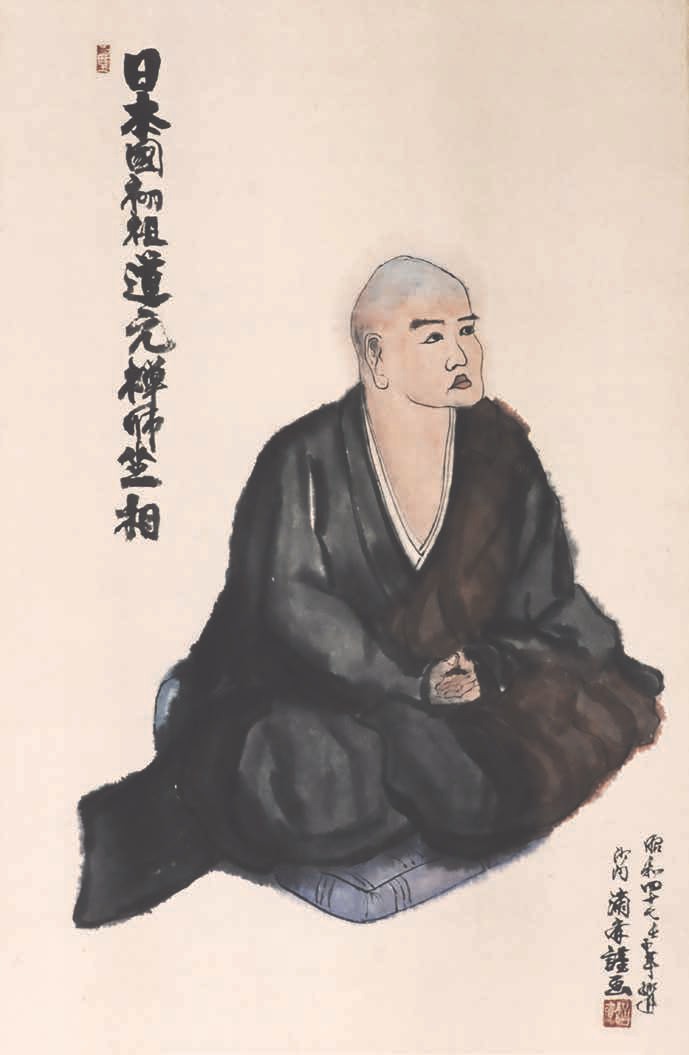

The word "Buddhism" is a Western one, first used in the early nineteenth century by British authors interpreting ancient teachings in a religious way. And though rights and rituals, myths and legends, as well as other elements of religiousness orbit all the traditions of Buddhism, the core teachings of the Buddha and the masters who followed his way have always been focused on an approach to life, the art of living skillfully in harmony with truth. This focus on living well and true is heavily emphasized in Zen. The "Homeless Monk," Kodo Sawaki, said, "A practice or Way that has nothing to do with our fundamental attitude toward our lives is nonsense. Buddhadharma is a practice of returning to a true way of life. Converting 'non-Buddhists' has nothing to do with changing religions or trading one belief system for another; it means helping people transform their lives from a makeshift, incomplete way to a genuine and true life." In Japanese, the teachings of a Zen master like Dogen are often called "shukyo," which is literally "truth teachings" ("shu" is truth and "kyo" is teaching).

In the Tenzo Kyokun, Dogen suggests that you "put your awakened mind to work." He is reminding us that without presence and heart, a lifetime will evaporate so quickly, pouring through our hands like water. Where is the time between your first awkward steps - a toddler-you stumbles by in the old photograph - and now, reading these very words? Vanished like a handful of dust brushed off the palms, even the last billowy puff carried by the wind into nothingness. Where will the time between now and your dying self, frail and doe-eyed, live and be? More snapshots of lost memories? How will the time feel as it passes? Do you not feel it racing away from you, faster and faster with every winter? Elsewhere in Dogen's collected works, called the Shobogenzo, or Treasury of the True Dharma Eye, Dogen argues that, for a human, our psychological impressions of time are actually more real to us than any system we use to measure time. In other words, our experience of time slows and speeds up, and that is a more important and relevant insight than measuring time from the outside by hours, weeks, months or years.

When Dogen says, "Put your awakened mind to work," he is saying that we mustn't live in the "makeshift" way that Master Sawaki discussed, but be "genuine" in all that we do. If we do that, we are then present unto our lives, living each moment as fully as it can be lived. In that way, we also honor our experience and lives. To be present, awake and listening, and to honor are two of the many lessons in the Tenzo Kyokun that I carry with me into tea and life, and they're each worth discussing and exploring together, you and I.

When Dogen was young, he traveled to China to study Zen. While there, he was deeply impacted by a meeting with a monastery cook (tenzo) aboard a ship, which he relates in the Instructions for the Cook. Dogen invites the old cook to share a meal with him and help him understand the teachings of Zen. The old man declines the invitation, saying that he needs to get back to the monastery to make the next day's morning meal, hinting at the honor that drives him to want to cook not out of obligation, but out of joy. Dogen then asks the old cook, "Venerable one, why take on the difficult task of cooking at your age? Why not practice Zazen (meditation) and contemplate the teachings of the masters until you are enlightened?" The old cook laughs and says that it is Dogen who needs to further contemplate the teachings of the masters, as he has yet to grasp the essence of Zen. When Dogen humbly asks him to explain, the master said to keep practicing and maybe he will penetrate the truth. He got up to leave, inviting Dogen to discuss this later at his monastery if he ever found himself in the neighborhood. The exchange affected the young Dogen very deeply.

In July of that same year, Dogen found himself at the old cook's monastery. The old man heard that the young foreigner was there and came to his room for tea. He said that he was retiring as tenzo that year. Dogen reminded him that he had said he would expound upon how cooking was the teachings of the masters if they met again. "At that time, you told me that if I want to understand words, I must look into what words are, and if I want to understand practice, I must understand what practice is. What are words?"

"One, two, three, four, five," says the old cook.

"What is practice?" asks Dogen.

"Everywhere, nothing is hidden."

Dogen digests the incident thus: "We talked about many other things but I won't go into that now. Suffice it to say that without the kindness and help of the old tenzo, I would not have had any understanding of words or of practice. When I told my late teacher Myozen about this he was very pleased." He realized then that practice has to be real; it has to be this very life, not words or ideas about how to live. He also understood the importance of cooking, which he later stressed in his writing and in the organization of the monastery he founded.

When you are cooking, the kitchen becomes your world. This is the same kind of training we are cultivating in tea ceremony. How you do anything is how you do everything. Each moment is an essential part of everything you leave behind in the world. At the end of your life, much more of what you experience will be in the category you've labeled "ordinary," which, if you're like me, is all too often foolishly dismissive in tone, suggesting that "ordinary" experience lacks value. First and foremost, I will never learn to live present, awake and listening to the world - learning and growing, showing up for my life - I will never cultivate such presence, so long as I separate experience into categories like "important" and "unimportant." And then again, life and time will tumble away without me really being there, a part of it all. Either all of it matters or none of it does! Besides, what could matter more than the way I make food for myself and others - the energy that fuels all and everything I experience, from glorious to mundane?

This means that cooking is done not as the kind of work where you punch in, daydream of being elsewhere, and then punch out and go do what you really want to be doing. "If a person entrusted with this work lacks such a spirit, then that person will endure unnecessary hardships and suffering that will have no value in their pursuit of the Way." Living and working in a Center like ours can be challenging - there is constant service of others and egoic conflict. Nowhere is this more pronounced than in the focused, concentrated and cluttered world of the kitchen. The tumbling of life and living in proximity with other unenlightened beings (especially within the heightened sensitivity that daily meditation brings) will wear you down if your orientation is not towards growth.

In the end, it is also we who are cooked with the food. We learn to be present, and to live and work without losing our composure. This is the art of tea and of life, as well. We learn not to be pulled off-center by our own or others' emotions - not reacting to someone's anger or our own feelings or ideas, which pull us away from the center of the moment. This is why Dogen suggests that the role of chief chef in the monastery, called "tenzo," is one for a mature practitioner who can use experience outside of the meditation hall - in the stream of daily work - as his practice since he doesn't get to meditate as often as the other monks. It doesn't matter how mature we are, we can practice cooking the way we want to live our lives. Shunryu Suzuki often spoke about finding your composure and settling there. He wasn't suggesting some kind of false, overly-formal way of holding yourself up, but rather not letting anything knock you off center. He meant staying oriented towards the moment, which means doing your work with care for every detail as if it were the most important thing in the universe. This requires a balance that will demand practice, though. We can really achieve such a composure by meditating and focusing on our daily activities, like tea and cooking, with sincerity.

In this and other works, Dogen clarifies the specifics of caring for our food, including balance amongst the flavors, which ultimately means that the food should nourish us in body and in soul. It should be delicious and nutritious. He also said cooking should be done in a light and adaptable way, which we could interpret to mean that cooking should come from the spirit, be creative and in harmony with the very vegetables before us, as opposed to following some generic recipe, which is an idea or conceptual interpretation of generic vegetables. Hard things break, struggling with a changing reality. We must remain light on our feet and bend a bit, like a good knife, using recipes only as a starting point. That keeps us connected to our cooking as it's happening, and to the moment as well.

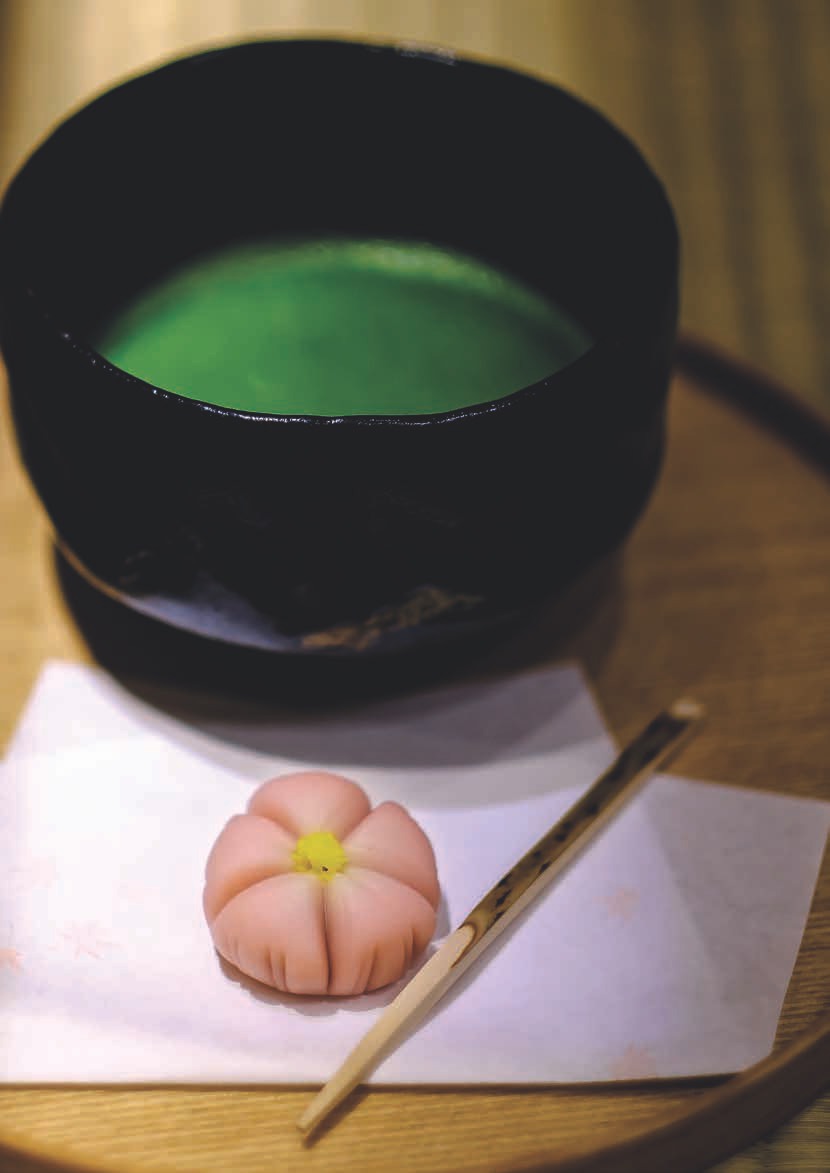

As a Zen master, Dogen also emphasizes the need for cleanliness in the kitchen, of course, which is also very much a principle of tea. My master always used to say that Cha Dao is eighty percent cleaning. Keeping the space clean helps maintain presence, spaciousness and lightness in cooking. It also means that our work leaves no trace, which is especially poignant in cooking, since the art is, ultimately, gobbled up.

Finally, Dogen advises that we be thorough and conscientious. Once again, this aligns with tea (which should come as no surprise, considering tea and Zen are "one flavor," after all). Being thorough and conscientious means that when we cut onions we do so without wasting energy or thought - just chopping onions. There are no unnecessary motions. There is a traditional belief in China that it is rude to talk while steeping tea, as the words will get in the liquor. Our words and thoughts influence the food, at least in distracting us from the reality of what is happening around us. Being awake and listening means being thorough, and being thorough requires that we be fully within what we are doing, investing our body and spirit into chopping, stirring or even washing dishes. This is a big part of how we put our heart into our tea, or into the food we cook, and this is how the art of cooking transforms and fuels the practice of those that eat it, as it is now full of dharma, as well as supporting our own practice in the mindful preparation. The flow should be smooth and coordinated, without wasted energy. This makes cooking a practice, and like Dogen suggests, we'll find that we're chopped with the onions, baked with the bread and stir-fried with the vegetables. Once we are really and truly awake in the kitchen, we start listening to the vegetables and pots. The pans awaken with us. They start clinging and clanging like the bells in the Zendo. The soup starts simmering sutras. We are now really hearing the true teachings of this world. This is where cooking, Zen practice and life meet.

Dogen spends a lot of time discussing the typical day in the life of a tenzo, describing the details intimately. The tenzo starts work in the afternoon, meeting with other senior monks to plan the next day's meal. Then there is the gathering of foodstuffs, prep work, cooking and coordinating with assistant cooks. Throughout the Tenzo Kyokun Dogen stresses not wasting food and honoring the preciousness of our life and the food we eat, which is the second important lesson I'd like to discuss. He says, "This life we live is a life of rejoicing, this body a body of joy, which can be used to present offerings to the Three Jewels. It arises through the merits of eons, and using it thus, its merit extends endlessly. I hope that you will work and cook in this way, using this body, which is the fruition of thousands of lifetimes and births to create limitless benefit for numberless beings." For me, this is, in part, a reminder to honor this life and to honor the sacrifice and effort in all the food we eat.

The Buddha said that a human life is as rare as a golden ring floating on an ocean where a tortoise that only comes up for air once every hundred years puts his head through that ring. At first this may seem silly, since there are billions of us. But we are surrounded by endless, empty space. Many of us often take these lives, these eyes and dreams, for granted, forgetting how much our ancestors suffered to give us these bodies. Many of our ancestors passed through wars and droughts and countless other trials, tribulations and turmoil to give us this experience we're having now. In fact, some of them knew no other joy save that of their children and grandchildren, literally living for our betterment. And how often we take this wonderful human experience for granted. Even in suffering, Zen teaches us to celebrate the pain as growth, to love the stone that sharpens us.

There is no greater treasure on this Earth than a human life. The richest zillionaire would give every penny he owns to live six months more. In fact, he'd give every cent for his daughter to live six months more! And though we hold the greatest treasure known, we still toy with baubles and trifles in the most unsatisfying way. Dogen reminds the cook that making food for such life is an honor, especially for those cultivating themselves, since the food then becomes an offering. Making food that fuels cultivation is one of the highest honors known, as it honors both life and practice.

Once you learn to be awake and listen, you must naturally cultivate the ability to honor this life. Gratitude for food is a very powerful way of doing this - in a very real, down-to-earth way. Honoring the food we cook is learning to honor the energy that supports the life I cultivate. In the Center, we light incense and pray to a kitchen altar before starting the preparation of any meal. Then, of course, we reflect on gratitude before eating as well. Dogen spends more time discussing the need to honor the sacrifice and effort in each meal. Whether you are vegetarian or not, living beings must give their life so that ours may continue. It is foolish to think that Mother Nature values her animal children more than her plant children. There is always sacrifice, and a true heart honors it. "A parent raises a child with deep love, regardless of poverty or difficulties. Their hearts cannot be understood by another; only a parent can understand it. A parent protects their child from heat or cold before worrying about whether they themselves are hot or cold. This kind of care can only be understood by those who have given rise to it, and realized only by those who practice it. This, brought to its fullest, is how you must care for water and rice, as though they were your own children."

The best way to honor the sacrifice of life given to your life is to live fully and cultivate yourself for the good of all beings. In that way, the sacrifice was not in vain, as it supported the evolution and liberation of consciousness. By holding the burden of sacrifice in our food, we are motivated to practice seriously, and to live our life to the fullest so that the energy sacrificed to us is honored; absorbed into a growing, light-giving journey. In that way, our food is truly fuel for the path to truth. All and everything honors such a sacrifice. "When we train in any of the offices of the monastery we should do so with a joyful heart, a motherly heart, a vast heart. A 'joyful heart' rejoices and recognizes meaning. You should consider that were you to be born in the realm of the shining beings, you would be absorbed in indulgence with the qualities of that realm so that you would not rouse the recognition of uncovering the Way and so have no opportunity to practice. And so how could you use cooking as an offering to the Three Jewels? Nothing is more excellent than the Three Jewels of the Buddha, the Truth and the Community of those who practice and realize the Way. Neither being the king of gods nor a world ruler can even compare with the Three Jewels."

Though most of us don't live in a monastery, or even an intentional community like the Tea Sage Hut, we can still be inspired by Dogen's words. There are actually countless other lessons in the Tenzo Kyokun. It's definitely worth taking the time to read. There are also great commentaries that shed light in other directions. For me, Dogen's motivation reminds me to invest more in this life as I live it, to be more present and awake. He encourages me to listen more, learning from everything around me, especially the small, seemingly unimportant parts of my day, like tea and cooking. And he pokes me, like any good Zen master, chiding the way I take my life for granted. I want to honor my life and my ancestors, both genetic and my lineage of teachers (including Dogen-Zenji himself ). I am grateful for the abundance of life-giving nourishment in my day, and I choose to honor that by preparing my food with devotion, thoroughly and conscientiously, by receiving food with prayers of gratitude and by not wasting the food given to me.

Cooking and eating is so central to all life, and supports all aspects of life, so there really is no way to have a meaningful practice without including the way we prepare and receive our food. Without this meal, there is no sunrise, no meditation and also no tea session. And the insight Dogen shares with me is that by turning my cooking into a practice, I affect all areas of my life, as every part of my day is fueled by whatever energy is in my food. I choose for it to be awakened and honored food!