|

|

For a Chajin, there really is no beginning to a tea session. Master Lin often says, "I have devoted fifty years of my life for the sake of this cup of tea." We put all of ourselves into the service of tea, and as a result this practice transforms us. For a formal session, you may want to spend as much time as possible planning the occasion, time and place to host your tea. You may want to send out themed invitations and create small gifts for your guests to take home based on that theme (maybe a small packet of the tea you're sharing). The more time you spend planning and creating the event, the more special it will be for your guests. There is no need to acknowledge this effort, as it will be in the heart of the event itself and your guests will feel that honor and love whether they recognize the particulars or not.

On the day of a ceremony, even a more casual one, you should spend time cleaning. We honor our guests by cleaning and decorating. In this way, we also honor the occasion itself; taking the time to make a session special is actually what does set it apart! Clean everywhere, even the places your guests will never see, as the purity of the space is a real energy and not just a show. After you have cleaned sufficiently, you can start on the chaxi.

As we have discussed in so many issues (we'll add some to the Further Readings this month on our blog), a chaxi is a mandala: a work of art that connects this occasion with the cosmos. The main function of this art is to honor your guests and the tea served. For that reason, it is important to choose your tea and brewing method before starting on your chaxi. After you've chosen a tea and brewing method, remember that the subject of any chaxi should be the tea itself. Arranging flowers for tea (chabana), for example, follows a very different aesthetic from ordinary flower arranging (ikebana), because the flowers cannot draw attention away from the tea and therefore need to be much simpler and more understated. In fact, simplicity is one of the main principles that should guide a well-designed chaxi. There are rarely neutral elements in art, and this is even truer of chaxi. If you aren't sure about how any element is enhancing the space, take it out. Less is truly more.

One Encounter, One Chance

One of the great tea sayings in the legacy of wisdom that has been handed down over generations is "ichigo ichie," which is Japanese for "one encounter, one chance." (The Chinese is below.) Any discussion of chaxi would be remiss without an exploration of this poignant expression, as it speaks to the underlying spirit of a great chaxi and the session that will take place upon it.

Before the session begins, this expression asks us to remember that this tea session we are preparing for is unique, pregnant with possibilities. It reminds us to treat it with the same respect and attention we would give to a once-in-a-lifetime meeting with someone very important, which it surely is.

Once the session has begun, ichigo ichie reminds us to cherish this moment, taking nothing for granted. Even if (especially if!) you and I drink tea together every day, even if it's the "same" room, the "same" time, the "same" tea, this saying reminds us that, in fact, nothing and nobody are ever the same. We are always sitting down to tea for the first and last time together. The whole Universe is changing every second, and so are we.

Anything at all that instills in us a sense of the uniqueness of this moment in time is worth contemplating. Nothing is guaranteed in this life. It's all a gift. We have no rights to it, we didn't earn it and we don't get to keep it as long as we want to. We don't even get to know when our lease is up. It has been granted us through some extraordinary fate, and everything can change in a flash. We just never know. We may not live out this very day. Such contemplations may sound dreary at first, but it is actually quite glorious, as it reminds us to celebrate and savor the experience we have left. And nothing helps you learn to appreciate each occasion like a tea practice, especially with a bit of one encounter, one chance heating up the water!

Technique: Work towards a theme (perhaps pre-planned). The more obvious themes are related to the event itself, like honoring a birthday or other life event; or you can always resort to basing your chaxi on Nature, connecting this occasion to what's happening around, like using autumn leaves on the table. More subtle themes can also be implied, like a sutra under the tea boat suggesting that the tea is soaking up lineage wisdom. There is no need to explain themes to your guests, though you can do so if you wish, especially if you are sending invitations beforehand. Most times, however, it is better to let them read into the session in whatever way resonates with them. As with any art, there are infinite insights and reflections available.

The art of making chaxi and preparing for a ceremony is a huge part of the respect that makes tea drinking into a ceremony, and you can continue this process into whatever depths you have a capacity for or your schedule allows. You can include the shirt of the brewer, which will also be a big part of what the guests see when they sit down. (Does it match the tea runner, for example?) You can decide whether or not to play music, whether to offer gifts, whether the decorations are just at the tea space or throughout the house, etc. The more we put into the session, the more special the occasion will be and the more honored our guests will feel.

This shouldn't make us feel like all tea sessions have to be formal - a formal session when the occasion calls for casual tea would be forced and ugly. But neither does that mean that casual sessions must necessarily be sloppy. You can celebrate the chance to have a casual gathering with friends as much as any formal occasion. It is, after all, a wonderful opportunity to have some time to chat with friends over tea! Why not celebrate that and make a chaxi that acknowledges, accentuates and encourages that type of tea? A skilled master of chaxi creates the perfect environment to support whatever tea and energy the session is trying to evoke - from formal ceremony to nice, down-home conversation.

We could wash the teaware before our guests arrive, but doing so in front of them is meant as a gesture of respect. It shows hospitality and cleanliness, offering them intimacy into as much of our tea preparation as possible. The respect the host has for the guests, as well as a desire to invite the guests into our practice and space, are the overt reason for cleaning the teaware in front of them, but there are also deeper internal reasons as well. There is not a need to express these internal reasons to your guests, though it is important for you to understand them, hold them in your heart and then let the gestures of cleaning the teaware express them without words.

Firstly, the washing of the teaware is a "temporary ordination," an idea that most modern cultures have lost. In the East, it was common for young people to spend time in the monastery finding themselves before making big life decisions, like who to marry and what to study. (I'm sure we could all have used more of that!) Beyond that, temporary ordination also meant that even wealthy businessmen could build a tea hut and garden in their back yard, and for a few hours a week live just as the hermit-monks in the mountains do. Many arts were born of this aesthetic, like bonsai, for example. Scholars would retreat to mountain temples when they had vacation time, writing poetry and living simply the way monks do. The tea ceremony is also one such space. In tea, we are all monks or nuns: social class, gender and our ego stories are all left outside with our shoes. We are all equal here - one heart sharing tea and wisdom together.

Most every tea tradition has some version of this temporary ordination. In Japan, tea huts often have very small doors called "nijiri-guchi," or "crawling-through doors," that people have to kneel to pass through, leaving behind status and ultimately all ego. Other Chajin have used ordination scepters in their chaxi to symbolize a setting down of all our stories for tea. In China, cities had unpaved roads and were dusty, whereas in the mountains, where holy men roamed and temple roofs made winged gestures at Heaven, the air was clear and clean. Consequently, it quickly became custom to discuss worldly matters in terms of "dust," especially "red dust," since the capital cities in the North often had red soil. We therefore wash the teaware in service of washing away all our ego-stuff, so that we can set down our background and show up equally pure and clean, resting in our highest beings for tea.

Washing the teaware and rinsing the tea is also a purification ritual like any done throughout ceremonies since the dawn of time - creating a purified space to host the guest of honor: Tea Herself. We wash the teaware and rinse the tea to clean off all Her travels, as well. We awaken tea from Her sleep and invite Her into our lives. As such, purification is an important preparatory step in any ceremony.

Finally, we wash the teaware and rinse the tea to wash off all our past sessions. Oftentimes, we forget to be present and miss out on the life that is passing us by all too quickly. By learning to honor this occasion, we learn to honor our very own lives. Sometimes people take a sip of a nice puerh, for example, and exclaim: "This puerh is wonderful... You know, I had another wonderful puerh two weeks ago at John's house..." And then three bowls of the puerh they themselves just said was "wonderful" go by unappreciated because they are talking about a puerh that no longer exists - lost in the past and missing the present. We are all prone to this. None of us celebrates the treasure of this life as much as we should. By washing the teaware and rinsing the tea, we are staying present to this very occasion and moment, which will never happen again - this "one encounter, one chance." Even if you buy several cakes of this puerh and take it home to brew over and over again it will never, ever taste like this again!

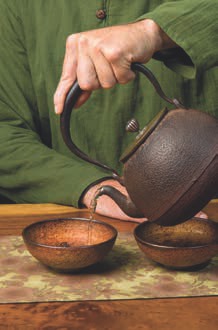

Technique: We wash the bowls by holding the bowl in the offhand. Make the offhand into a bicycle fork, with the thumb forming one side and the four fingers held together forming the other side of the fork. This hand does not move. (This will be very important if you are to rinse the bowls properly.) The bowl spins through this hand much like the wheel of the bicycle spins through the fork. The strong hand then grips the ring of the bowl and spins it towards you (you don't want to pass unclean water towards your guests). Hold the bowl at a forty-five degree angle. The ideal is to have the water clean the inside of the bowl as well as the outside of the rim where your guests' mouths will be touching. In order to achieve this effect, you will have to master the correct angle and speed. The speed will be more difficult than it sounds, so you may want to practice at first with cooler water. If you go too slow, the water will run over the edge and down to your hand, burning you; and if you go too fast, it will shoot out and won't clean the outside rim. Like most things, you have to do it just right. You will know when you have cleaned the entire way around the bowl because you will feel the wetness return to the thumb part of your forked offhand. At that point, put the palm of your offhand into the curve of the bowl, much like a martial arts palm-attack, while holding on with the strong hand, and shake the bowl up and down to flush out the last drips of the excess water. Then, repeat this for every bowl, making sure to clean your own last.

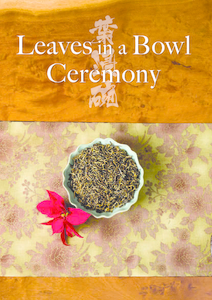

Once you have washed all the bowls, you can add the leaves. When we prepare leaves in a bowl, we often include the leaves themselves in the chaxi - often in a large bowl at the center of the table. Use a large open bowl that makes it easy to grab the leaves. Teas with long, striped leaves are ideal for leaves in a bowl tea, as they won't get caught in your guests' mouths and are more beautiful opening in the bowl. As your guests are sitting down, you can invite them to appreciate the leaves if you like, which they often enjoy. They may have questions, which you can then get out of the way at that time or politely postpone until after the ceremony.

Since the brewing starts here, this is a good place to review the Five Basics of Tea Brewing, which will help you throughout your entire tea journey. We will post some articles that go into each of the basics in greater depth in the "Further Readings" section of our blog this month (there is also a nice video on our YouTube channel). In summary, they are: to divide the space in half and do everything on the right side with the right hand and vice versa, all circular motions move towards the center, always keep the kettle in your offhand, never (ever, times ten) pick up the kettle until you've stilled your heart-mind and, finally, stay focused and concentrated on tea preparation until handing the tea to your guests.

Once we are ready to start the tea brewing, we like to bow to our guests. More than the obvious show of respect, this bow is also a kind of apology, as you will be excusing yourself from the role of host to focus completely on the tea. You are asking them to allow you to ignore them, so that you can honor them by making the best tea you can, which will, of course, demand all your heart and attention. If you are serving guests who are new to tea ceremony, you may want to mention out loud that you will be sharing some tea together in silence, with time to talk and ask questions afterwards. For especially agitated guests, it is also helpful to tell them how many bowls, as indeterminate silence can be uncomfortable for some people. By saying out loud that you'll share three bowls in quiet, for example, can make the space much more comfortable.

We need hot water to help open the leaves in this style of brewing. However, since the water is going directly into the bowls, you may want to experiment with taking the kettle off the stove for several seconds, or even a couple minutes depending on the kettle, to make sure the water is cool enough that the bowls can be held comfortably. After the first steeping, you can use cooler water. You may also want to let the tea steep for a minute or two each round before handing the bowls out.

It is very helpful to hold the kettle properly. Holding it in the off hand will become increasingly important as you develop your tea brewing skills. In doing so, you increase the fluency of brewing, especially when you move on to gongfu tea. Some people hold the kettle at the back of the handle with their fist, forcing their arm sideways. This may seem more comfortable, especially if you are using a heavy kettle, but it really only has an "on" and "off," meaning that there are much less gradations of pour and flow this way,severely limiting your control over the degree of water flow and the circular precision. As we progress in tea brewing, we learn not to pour the tea into the pot or bowl, but to place it where we want. In other words, precision becomes more and more important over time.

The best way to hold the kettle is with your index finger running down the handle. Your hand should be as close to the center of balance of the handle as possible, which will differ from kettle to kettle. Experiment with water and various methods of holding the kettle. You will see that having your index finger run down the handle offers a lot more control over the power of the stream and much more precision when seeking a point anywhere in the circular range you have with the kettle. This is especially important in gongfu tea when showering the pot in the wrong place, for example, makes the lid too hot and therefore difficult to grab.

Technique: There are two useful skills in adding the leaves to the bowl and steeping them. The first is to use your thumb and fingers and pinch the leaves upward from the bowl and release them. This separates the small bits, which fall to the bottom of the dish. This will make it easier to choose large, beautiful leaves for each bowl. How much you add depends on the kind of tea: for sheng, we like to add one large leaf and one budset, if possible. Red tea, on the other hand, is nice when it is a bit stronger, so you may want to add five to seven leaves if you're making this month's tea. The second skill that is useful is to make the leaves spin when you pour the water. In the first steeping, this helps pull the leaves under the water so that they start steeping right away, instead of floating for a long time. In later steepings, the leaves will be stuck to the bottom of the bowl, so this technique is helpful for lifting them off so that every leaf steeps evenly. To do this you will have to get to know your kettle and bowls. We want the spin to move around at a slightly downward angle as opposed to just going in flat, horizontal circles, which wouldn't pull the leaves under in the first steeping. Try starting with a thinner pour from the kettle and move along the side of the bowl furthest from you until you find the place where the leaves start to spin, at which point you can increase the flow of water - "turn on the gas," as Wu De often says. After some time, you will get to know your kettle and bowls and will be able to do this rapidly without hunting for the right spot.

Sometimes when people come into ceremonial space, they may find it heavy. They may not know that when you bowed before serving that you were excusing yourself, and wonder why you are ignoring them. The intent look on your face, as you focus all your heart and soul on tea brewing, may feel intimidating. And, let's face it, not everyone is comfortable with silence, as it shifts the whole world inward and we all fear looking inwards to some extent. Whether your guests are beginners or seasoned tea drinkers, it helps to show that a session is not heavy and that all our energy is bent on perfect hospitality. There will be plenty of time to move inward and rest in peace or take a journey, but it helps to connect to all your guests in the beginning of each and every tea ceremony.

Before serving the first bowl, we like to make eye contact with each of our guests one by one. Bring their bowl to your heart and look at each of your guests in turn. You can smile at them or bow. Whatever you do, make sure that you communicate welcome and warmth, hospitality and love. This one gesture goes a long way towards making the silence of a tea ceremony into a joyful silence, rather than something heavy and/or intimidating. Feelings that this space is unapproachable or uncomfortable will be deflated and everyone can then spend the rest of the session focusing on the tea. We only do this for the first bowl.

Technique: When bringing the bowl to your heart each time, be sure to switch hands halfway round the table, so that the guide hand holding the bowl from the top will switch from the right hand for the right side to the left hand on the left side. This allows you to place the bowl before each guest with the proper hand. Once the bowl is by the heart, you can place your open palm over it and fill it with all your heart and hospitality as you make deep and meaningful eye contact with each guest - an exercise that can be challenging for some, forcing us to confront others openly and honestly.

The coming and going of the bowls or cups is the breath of the tea ceremony. We are separate individuals and we are also one - one gathering resting in one heart space. The tides of together and apart mark the pace of a tea ceremony, and if you have defined a limit to the silence, it will also determine when you can start conversation again. Always try to bow and initiate the conversation yourself. As the host, it will be your job to steer any conversation towards meaningful, heart-centered topics.

Each round, wait for your guests to finish their tea, being sure not to rush them in any way. If you are a guest and want to pass on a round of tea, you are always free to do so. We must listen to our bodies when it comes to taking plant medicine. Simply place your hand palm down over your bowl on the table as the host is gathering the bowls and he or she will know that you want to skip this round.

When serving, make sure you keep the same order every time. This is usually achieved by putting your own bowl to the far side of your strong hand. Also, always be sure to fill your own bowl last. Hand them out in reverse order each time, from right to left and left to right. That way, each guest will get a nice hot bowl at least every other turn. This also helps keep you mindful and focused as the rounds pass.

Technique: When we hand each bowl out with one hand (depending on the side of the table), we open the wrist outward, which is the one exception to the second basic principle that all circular movements are towards the center. This turning of the bowl outward offers the guest to drink from the part of the bowl that your hand was not on. It is also a gesture that harkens back to a simpler time when everyone in the community shared from a single bowl and turned it to offer the next person the part of the bowl where their lips had not been. The revolution of a single bowl in circles, and in orbit around the gathering, connected the tea ceremony to the celestial movements of the Earth. It is nice to share a single bowl between you and your guests if you want, but even with many bowls, this turn of the bowl is to represent that though we all drink from separate bowls, we share in the same Tea spirit. Tea connects, bringing people together. This gesture symbolizes drinking from one bowl, and not just those who are present, but all the bowls that have ever been drunk through time, starting with old Shen Nong himself!

When a ceremony doesn't end, guests are left with an incomplete feeling. It is always worth ending what you've started. One of the best ways to end a leaves in a bowl ceremony is with a bowl of water. There is an old Chinese saying that "friendship between the noble is like clear spring water - it leaves no trace."

Simply, quickly and deftly scoop the leaves from each bowl and place them in the wastewater dish. Then, rinse the bowls one by one again in the same way you did at the start of the ceremony. Finally, add some water to each bowl. You may want to leave the kettle off the stove in anticipation of this, since you don't want the water to be too hot. After serving water, bow to your guests one more time to complete the ceremony, show respect to them and to excuse yourself for breaking the noble silence.

Always leave ample time to clean up a tea ceremony, as it too should "leave no trace." Honoring the session, tea and teaware means cleaning up completely. By taking the time to always clean up, we honor this practice. If this is my means of cultivation, it should be tight, clean and clear. After all, a cluttered altar means a sloppy relationship to the Divine, and, in this case, to Nature and the spirit of Tea as well.

It is also a wonderful practice to sit in the tea space after your guests have left and spend ten or fifteen minutes cleaning and drying the bowls, while at the same time celebrating the wonderful occasion you just had the fortune to be a part of, acknowledging with gratitude the time and heart to honor such a space. Then, you may want to wish each of your guests a fare-thee-well in turn, hoping that the ceremony which has just occurred carries them to fortune and happiness. Contemplate each of their faces in turn, filling your heart with loving-kindness. Be grateful for the occasion and for their company as you clean up your teaware and put it away, clean off the chaxi and wipe the table or floor down, leaving no trace of the "one encounter, one chance" that has just occurred.