|

|

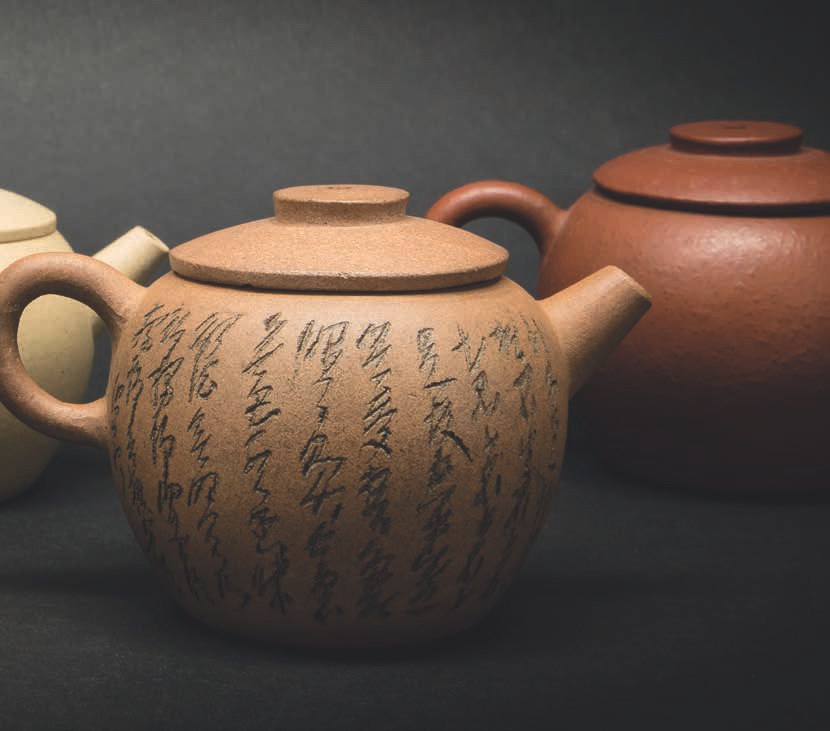

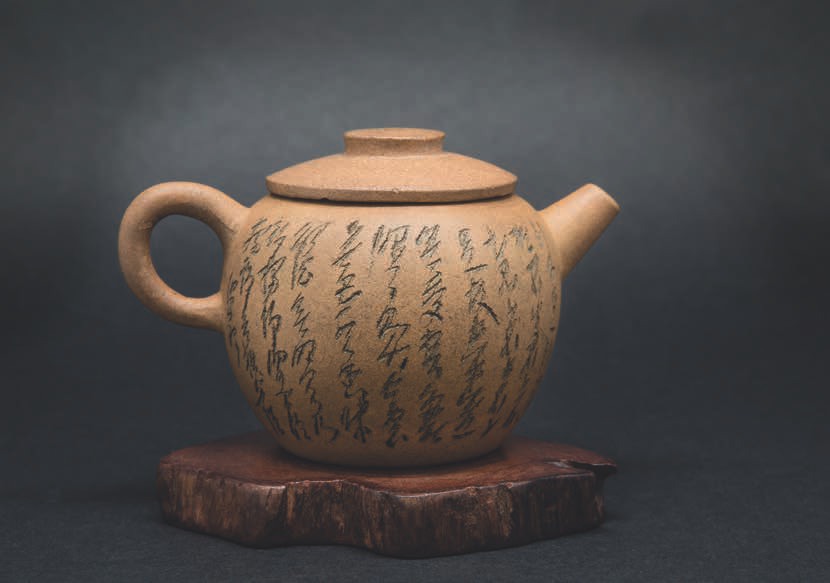

Very early on in my tea journey, I noticed that most of the tea teachers I was learning from all used the same style of Yixing purple-sand pot (zisha, 紫砂) when preparing gongfu tea: with a large, flat and round button, jar-shaped body and a cannon spout. Later, I found out that these pots are called "wagon wheel pots (ju lun ju, 巨輪珠)." And every teacher I respected had at least one, while many seemed to use them exclusively. These humble brown-topurple pots spoke to me, as they do to most tea lovers. They suit the aesthetic of tea: simple, unadorned, modest and yet somehow powerful. Wagon wheel pots are like the old Daoist master who walks around in plain sight, looking like everyone else but holding deep and profound teachings most people will pass by. From the beginning, I suspected that these pots also held deeper truths - that there was more to them than a pleasing simplicity. "Do they make better tea?" I wondered. And so, like my teachers before me, I looked past the plain and often crude shapes of wagon wheel pots to the dark and mysterious elixir steeping within, searching for the secrets these old pots had to tell.

In the eighteenth century, several Japanese tea lovers began resisting what they perceived to be an excessive formality and constriction in Chanoyu. They cultivated nostalgia for the scholar poets of ancient China, creating retreat homes in the mountains where they appreciated Nature, painting, calligraphy, poetry, music, the classics and a revitalized tea practice focused on steeped tea, called "sencha do," literally "the Way of sencha." Sencha had been around in Japan for some time, but the name technically refers to "simmered/boiled tea," which is how it was prepared up until these Edo tea lovers started steeping Japanese, and, to a lesser extent, Chinese teas. This would, of course, influence the way tea was produced, forever changing Japanese tea farming, production and appreciation.

Throughout much of the history of Japanese tea, there was a preference for Chinese antiques that sometimes got out of hand, resulting in collectors paying a fortune for pieces. This is, in part, why Master Rikyu turned to local raku potters for his bowls, suggesting that tea and teaware celebrate simplicity. It should come as no surprise, then, that the later tea lovers who began practicing steeped tea fell in love with Yixing purple-sand teaware. At the time, only the port of Nagasaki was open for legal import, and goods were heavily taxed. And some zisha pots were more valuable than silver. Most of the poets, artists and scholars interested in steeped tea were wealthy, though, and began collecting and eventually commissioning Yixing teaware for their practice.

And this brings us to the most obvious reason that tea teachers today favor wagon wheel pots: their simplicity. During the Edo period, as the Way of sencha was beginning in Japan, the Qing Dynasty (1644 - 1911) was at its peak under the rule of Qianlong. The arts flourished under his long reign (officially 1735 - 1796, though he actually retained power until his death in 1799). Like all works of art, Yixing teapots rose in quality and beauty. However, as many new aesthetic trends began, and pots became more and more elegant, some of the simplicity that tea lovers celebrated in Yixingware was lost. Potters began producing more complicated, decorative pots in new styles, each expanding on traditional forms - most of which began in the Ming Dynasty (1368 - 1644). As mentioned above, the new Japanese tradition of steeped tea was begun mostly out of a push against what they saw as constriction in Chanoyu coupled with a deep nostalgia for classical Chinese culture (often over-glorified to the point of myth). They sought to live like the Daoist masters of old, skilled in brush and in life. Consequently, these tea lovers favored simpler, older styles of teapots that celebrated the simple, free and unadorned style of brewing they were cultivating, as well as the antique, rustic, hermit-like aesthetic they were creating. Over the next two centuries, countless wagon wheel pots would be commissioned and sent to Japan.

The true wagon wheel shape, with the large, flat button became popular in the late Qing Dynasty (Meiji in Japan), and hundreds of these pots were exported - more and more as trade increased and Japan opened up its ports. Later, in the 1970s and '80s, when Taiwanese tea scholars began to write books about Yixing teaware, they categorized all the pots that were exported to Japan as "wagon wheel," even though the earlier pots didn't actually have the large, flat button that characterizes this type of pot. The name has stuck, though, and tea lovers today also call any pot in this style "ju lun ju." Not all "wagon wheel" pots have a wagon wheel button, but they all were exported to Japan, have cannon spouts and are simple, and sometimes even crude in design. As you can see, the simplicity of wagon wheel pots is where an appreciation of them begins and ends.

As the years have passed and I have traveled further in my gongfu tea practice, I have reduced and simplified both for functional and aesthetic reasons. When I started my tea journey, I watched my teachers use the simplest of wares and brewing methods, and wondered why they weren't attracted to the elegant wares and ways I was: the curvy pots, dragon-egg pots inlaid with silver, and many other examples of the amazing heritage of skill and mastery in antique and modern teaware alike. But as time passes, one finds that like Lu Yu said so long ago in the oldest surviving work on tea, the Cha Jing, "The spirit of tea is frugality." As my life, practice and tea simplified, the unadorned wagon wheel pots of my teachers started to sparkle with the ordinary glow that Tea teaches us to celebrate. The understated lines and elevation of function over form started to shine more brightly as the cups and bowls of tea passed by with the seasons, each sip showing me in true Zen form just how special, important and bountiful the most ordinary moments and objects can be. Frugality, indeed.

As the wagon wheel turned, I began to discover more and deeper reasons why nearly all tea teachers favor these magical pots. Beyond simplicity, availability and price have played a role in the widespread love for these pots. Cultural habits, happenstance and history have changed the destiny of these pots, and put them on the shelves of so many tea lovers around the world.

Japan has always been prone to earthquakes, which means that collectors of anything fragile have learned over time to be protective. As I mentioned earlier, the first zisha pots to be exported to Japan were often worth more than silver. They were wrapped carefully in cloth and stored in wooden boxes and then in safe cabinets. Japanese people are also famously careful and focused in their daily lives, and due to the influence of Zen, they also cultivated an appreciation of and devotion to the simple. The teapots there were not only cared for more deeply, but also in a different way.

One of the magic things about antique teaware (of many) is the people who have used the piece over time, and the energy they've left behind on it. In general, this is another reason that tea teachers favor simple, old teaware, as fancy teaware made for wealthy patrons often sits on shelves, used less often than the simple cups or pots used every day by simple, kind-hearted, ordinary folk. Beyond that, the Chajin in Japan at that time all had a more overtly spiritual relationship to tea. Many of these pots found their way into the hands of monks, for example. Since zisha pots were so rare and Japanese people treasured them as aspects of their spiritual cultivation, these wagon wheel pots were often deeply honored. We have a few in the Center that were named, and then later owners wrote beautiful poems on the box that protects them - poems with lines like "may the liquor ever flow from this pot in streams of enlightenment." Having a teapot that was passed down with such reverence and care definitely makes a difference in the way it feels, if not in the tea you can make with it.

Because teapots were more common in China, a lot of people didn't take as good care of them. Also, the Communist Revolution of 1949, and the subsequent Cultural Revolution, destroyed a lot of "old" things, which meant that much less antique teaware survived in China. Beyond the radiance lent to wagon wheel pots by the heart and spirit of the Japanese Chajin who loved and treasured them, there is the very practical truth that a lot more of these pots survived to the present time and many in mint (or near mint) condition.

As we fast-forward to the modern era, a tea lover looking for a nice antique teapot has a much better chance of finding a wagon wheel than anything else. Modern Japanese don't value them as much as Chinese collectors, though that is changing as they become rarer. Also, there are more of them and they are in great condition, often with a custom box. Finally, teapot collectors are very rarely interested in wagon wheel pots. They collect pots made by famous artists, pots that are elegant and beautiful, made of rare clay or that stand out in some other way. Once again, in true Daoist form, the simplicity and crudeness of wagon wheel pots means that they have always been ignored by collectors, which also means they are always cheaper. And if you are looking for a teapot to make tea, rather than a collector's item, a cheaper price makes a big difference. Sure, wagon wheel pots are gorgeous in their simplicity, if you have the eye to appreciate them, and there are many more of them and in better shape (and for lower prices), but what about where it counts? Do they make better tea? If so, why?

As we discussed earlier, so-called "wagon wheel" pots come in a variety of shapes and sizes, though the large, flat-buttoned ones are the most common, since more of those were exported to Japan later on. But the one thing they all have in common, aside from a simple form, is the cannon spout. And therein lies one of the deeper reasons why tea lovers favor them, and the one reason that actually applies to brewing as opposed to an aesthetic preference or just the happenstance that there are more of them available for less money. (There are other reasons why wagon wheel pots make great tea, but they will have to wait for a future article, as this is just a general introduction.)

For beginners, a spout with a limited range of flow, speed and distance is very helpful. Each spout has a range of pour, which means the amount and speed that the tea liquor comes out of the spout. The greater the range, the more you can control whether the pour is soft and slight or fast and gushing. The shape of the spout also determines the distance from the pot itself that the stream will pour. The greater this range is, the more you can choose to pour straight down or to a distance of several inches. There is always some room to work with any pot, but when you are starting out, it is helpful if the ranges of both the flow and distance are narrower. In other words, you want the pot to help you, as opposed to offering a huge array of speeds, flows and distances of pour. This will make your tea smoother, more precise and much less sloppy overall, since beginners will find that it is difficult to control a wide range with any degree of accuracy or consistency. There will be a lot of spillage, in other words, and little control over the flow.

With the cannon spouts of wagon wheel pots, the range is as wide as any pot can be. This frustrates beginners, as they find themselves dribbling, dumping out small bits of tea leaves and often spilling. But as your practice advances, the freedom this range affords you starts to become more and more spectacular. This progress is true of the equipment used in any art. In photography, it is often helpful to start with a camera that helps you. Cameras have advanced a lot these days, and those with technology that allows you to focus more on composition and other aspects of the art are very helpful as you learn. But the further you go in this art, the more manual control you want over the camera. What was helpful before becomes restrictive. You want more freedom, at least in most situations. Similarly, as time has passed and I have gained more control over the teapot, the range of flow and distance I can pour with a wagon wheel pot makes a huge difference in making better tea, especially as I've become sensitive to how the distance, speed and flow of the pour affect different kinds of tea. For example, puerh is much better poured quickly.

There is a lot more to say about these simple, yet profound pots. Like the wooden wheels after which they are named, they are simple, ordinary pots used to make tea on a day-to-day basis, not rare collector's items for special occasions. And also like the wheel, they are a very profound part of our history and growth. I will try to come back to these magical pots - the most important of the gongfu treasures in the Center - in future issues, sharing more of my experience with them over the years.

However, this article may also inspire some deeper, underlying questions amongst the many insightful Global Tea Hut readers out there, like why choose an antique pot over a modern one, wagon wheel or otherwise? Why not just commission a modern potter to make a wagon wheel pot? That may be a good choice for many of us, and if you can find the right potter, you may wind up with a great pot indeed, but as you can see, we still favor antique ones, and for good reasons. I'm glad you've asked these questions while reading this article, but the answers to why an antique Yixing is so much better than a modern one will have to wait until a future session of Gongfu Teapot...