|

|

The aging of tea is a magical thing. Fermentation is the least understood of all aspects of our food production and consumption. The word "ferment" literally means "to boil," the bubbling of fermenting liquid. Our ancestors believed this was a gift from the gods, and surrounded the transformation of fermented foods and drinks with ceremony. More than a third of what we eat and drink is fermented by microbes, and, by number, most of all the cells in our bodies are also bacteria. The microbial world is vast, and our journey into it is relatively recent, even though humans have fermented things long before there was even a concept of "microbe." And as we do explore fermentation more, learning about the science of microscopic anaerobic change, we shouldn't forget that understanding how something happens doesn't make it any less awe-some, magical or mysterious. The alchemy of transformation through aging tea leaves will always be magical, no matter how much research is conducted or how much we learn about how the process works.

There are a lot of ideas out there on how to age puerh tea, what "wet" and "dry" storage refer to and what conditions produce the best aging process, including artificial means. We plan to expose you to some different perspectives on the issue, learning from the experience of various puerh lovers who have stored tea for some time. Though their opinions differ, they all have experience drinking mature puerh tea and in watching it age over time. Our goal over the coming years is to publish more and more perspectives on the topics we cover, including translations of Chinese articles. It is never enough to learn from just one source, and important for us to cover varying perspectives to offer a more holistic understanding of tea. In the case of aging puerh, it is important to note that experience in drinking lots of mature puerh, and in watching puerh change over long periods, is necessary. Without this, those who are writing about how to store puerh aren't really qualified to teach. These days you can find a lot of information circulating online about the aging of puerh tea that is written by enthusiasts or vendors without experience drinking a lot of mature puerh, which means they haven't a clear understanding of what represents well-stored puerh (the goals of storage, in other words), nor do they have experience storing tea for long periods of time, and therefore haven't learned from all the mistakes one makes over time or how to correct them.

Any genre of tea can be aged, and if a fine tea is kept for a long period it will be marvelous, no matter what kind of tea it is. Oftentimes, the merchants of lighter teas, like lightly-oxidized oolong, green, white or yellow tea pressure the tea lover to drink the tea fresh, as though it has an expiry date. There is a magic in the freshness of such tea, and that is lost when aged, but such teas can technically be aged. That said, they take longer to reach maturity and will pass through a longer, awkward stage as they dry out, since they have a higher moisture content. Still, space is limited for all of us, not to mention the investment of time and energy spent aging anything for a long period of time. Therefore, such teas are rarely ideal candidates for long-term storage and the examples around were not intentionally stored, but rather left behind.

While aged oolong is magnificent, no tea ages like puerh. This is due to the microbial diversity found in the rainforests of Yunnan, where authentic puerh trees are found. Long before puerh tea is even picked, the leaves and trees are covered in hundreds of species of molds, bacteria and fungi. These tea trees are teeming with life, covered in molds and insects. This relationship makes this tea much more conducive to post-production fermentation. As we discussed, the low-temperature firing and sun-drying facilitates this fermentation further.

It is very important to distinguish between short-term and long-term aging. We would define short-term aging as keeping the tea while you consume it, storing the tea in a jar and then drinking it. The main topic of this issue, however, is much more about long-term aging, which means intentionally aging tea for long periods. This could include oolong and other teas, but in this issue we are going to focus on puerh. The criteria for shortterm versus long-term aging are very different. For short-term aging, which is essentially just storing the tea while you drink it, it is best to keep it in a jar, broken up if it is in cake form. As for long-term aging, this issue will explore that topic, and, as we mentioned, we will most likely have to continue to discuss it in future issues as well, since it is such a vast topic, and one with many different perspectives.

In this issue, we will have several discussions on puerh aging from howto guides from several perspectives to the science of change within the leaf, or what we understand about it so far. In this introduction article, we want to focus on some of the more important questions that come up all the time via email, at Wu De's workshops and here at the Hut, answering them as best we can. Let us know via email or social media if you enjoy this question-andanswer format, as we are discussing including one section of such Q&As in some of our coming issues. If your question isn't answered here, it is most likely because it is covered in one or more of the coming articles.

Master Lin always says, "If you want to be abundant, age tea." As you progress on your tea journey, your own passion and taste will lead you to darker, traditionally processed, skillfully made or aged teas. Puerh transforms so powerfully over time, becoming a much more delicious brew, but also, more importantly, a deeper medicine for the soul. No tea is as conducive to meditation, ceremonial space or inner healing as aged puerh tea. It is as if the tea accumulates wisdom in that jar, as if the leaves and the species of microbes build temples in there and start sitting together.

If you don't age tea, you will pay someone else to. This is one of the reasons aged tea is so expensive: it requires a lot of time and energy to age it. You have to pay for the space and electricity. Also, puerh is a large investment these days. It used to be that young sheng puerh was very, very inexpensive and you could therefore store it simply, but since it is so costly these days, the storage facilities have also been upgraded with charcoal (to remove impurities from the air), and sometime controlled ventilation, proper shelving, etc. And all of that gets expensive.

If you want to have lots of aged tea to share and not feel like it is a very rare tea only for very special occasions, then you have to age it for yourself. Doing so allows you to be generous with such powerful medicine, sharing it freely and every day, which is the spirit of tea. Also, according to Traditional Chinese Medicine, aged puerh slows down senescence if you consume it daily, so having lots of it around when you are older might just grant you more longevity, tea gods willing.

There is a lot we don't understand about puerh fermentation scientifically, as there have not been enough studies. Based on the experience of those that have aged it for generations, the most important factor is humidity. The microbes in puerh can defend themselves from foreign colonies to some extent, but they need airflow, comfortable warmth and humidity to thrive. As you will see in the articles throughout this issue, the right humidity is a debated topic. Our experience at the Center is that a humidity of 60 to 70 percent is ideal, with natural fluctuations. This is referring to the humidity in the room the tea is stored in, not outdoors, which may or may not be different, depending on how much air-conditioning and/or heating you use.

Traditionally, puerh was thought to reach full maturity at seventy years. This is the point at which the physical appearance of the tea liquor will not change anymore. It has become a dark black that fades into brown, maroon and light brown with a golden ring at the edge. The tea will continue to change, especially in the way it stimulates Qi in us, as well as flavor, but does so at a very slow rate so that you really have to wait decades to have a noticeable difference, unless you are sensitive and focusing on very subtle changes. All astringency is now gone from the tea, which has become sweet, deep and dark with flavors of ginseng, medicinal herbs, sandalwood, plum and other analogous flavors.

Puerh transforms in five- to seven-year cycles, depending on the environment it is stored in. Some of the early shifts, after five and then ten years, can be what we call "awkward stages," since the tea can sometimes taste strange, often of spices. At around fifteen and then twenty years, the liquor starts to turn more brown and the tea starts to really feel aged. The longer the aging, the more the process slows down. In other words, everyone can tell the difference between a one- and three-year-old tea, and same with five and ten. A ten-year-old and a fifteen-year-old are a bit harder to tell apart, and may require some experience with aging and/ or drinking various vintages. Eventually, the tea is measured in decades.

The only place to have successfully aged puerh tea to full maturity is Southeast Asia, mostly Hong Kong, Taiwan and Malaysia. Traditionally, places like Jinhong in Yunnan were also used.

If you are aging nice, expensive cakes or aging in large quantities, we would suggest choosing a traditional location. However, in small quantities, it may be nice to see what tea aged in your home is like over time, and even if it doesn't turn out well, you won't have lost much. Also, check the humidity in your storage room over time. If it is too dry, the tea definitely won't age well.

Puerh tea ages much better in cake form. We have participated in many experiments tasting the same tea in cake and loose-leaf form after it has been aged to different degrees. The cake tea always ages better, which may be due to the fact that the steam during compression makes an ideal environment for the microbes to live and thrive in a cake. This also explains why teas with looser compression age better than those which are too tightly compressed. Loose-leaf tea tends to age quicker and becomes too wet very easily. It is much more difficult to maintain a clean storage in a jar than in a cake.

Puerh for drinking is the opposite: it is better to break it up. We have discussed this, and the results of our experiments, in a few past issues. After aging puerh for some time, the inside has not been exposed to oxygen and needs to breathe, so it is always better to break your cake up and store it in a jar, leaving it for a month or so before you start drinking it.

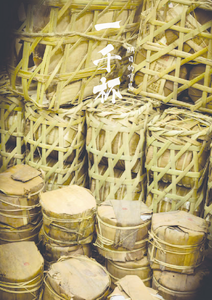

As you may or may not know, puerh lovers traditionally buy cakes they like in eight pieces (a tong and a cake). The bamboo skin wrapping of a seven-cake tong protects the tea from humidity and too much air, and once again we find bamboo to be the long-term friend of tea. Like most plants, the bamboo in Yunnan is huge, and as it grows it sheds its skin in large pieces that are then used to wrap the tea. Since the tea is better drunk all broken up and better aged in a cake, having a tong and a cake allows the puerh lover the best of both worlds. The extra cake then becomes a tester, which you can drink from every few years to determine when the tea has fermented enough that you'd like to start enjoying it. At that point, you can break up a cake from the tong and carefully reseal it, putting the broken cake in a jar. Sometimes, we keep the tester, as we may want a gap between the cakes we break up to enjoy, and can then return to the tester to decide when to dip back into the tong for a second cake.

Mold is not necessarily bad for puerh tea. All puerh tea has spores in it. The trees in Yunnan themselves are covered in mold. Most of us have been raised with some degree of germaphobia and will react to some mold on our puerh. But steeped in boiling water, all the mold spores will die anyway. As for the quality of the tea and its aging, it is natural for there to be annual frosting of some white mold. We want to make sure this doesn't get too strong, as it is a symptom of the fact that the tea is being stored too wet and therefore fermenting too fast. The mold is, in other words, a symptom rather than the problem. Some kinds of mold definitely can damage puerh tea. The traditional wisdom is that all white mold is okay, some yellow and gold, while black, orange, blue or green are bad signs that mean the tea has spoiled.

If you find mold, separate the affected cakes and brush them off. You can also leave them out in the morning sun before it gets too hot at noon. Make sure the mold hasn't spread to the nearby cakes. You should also move all your cakes to a drier location for some years, as the mold is a sure sign that your tea is being stored in a location that is too damp.

We participated in some blind tea tastings for a couple different Chinese magazines, in which tea stored in such controlled environments was compared to that which was naturally aged. The difference was huge enough for us to warn against this. Find natural ways to increase humidity, like storage jars or different locations in the house. Traditionally, so-called "wet storage" in Hong Kong rarely used artificial means to speed up or increase fermentation. More often, these merchants would simply choose warehouses or rooms that naturally had higher humidity, like basements or buildings by the sea. The same is true for keeping tea drier when you live in a place that can be too humid, like Taiwan. We store the Center's tea on the third floor of the office, which is a bit drier.

Every few years, try the tea and see if it is aging properly. You can look at the cake and smell the dry leaves, drink the tea and also examine the wet leaves. This allows you to shift the tea to drier or wetter conditions, if need be. Remember that storage is long term, so most imbalances can be corrected over time, especially if you check on the tea regularly (every two to three years) and thereby quickly correct it if it is heading down the wrong road.