|

|

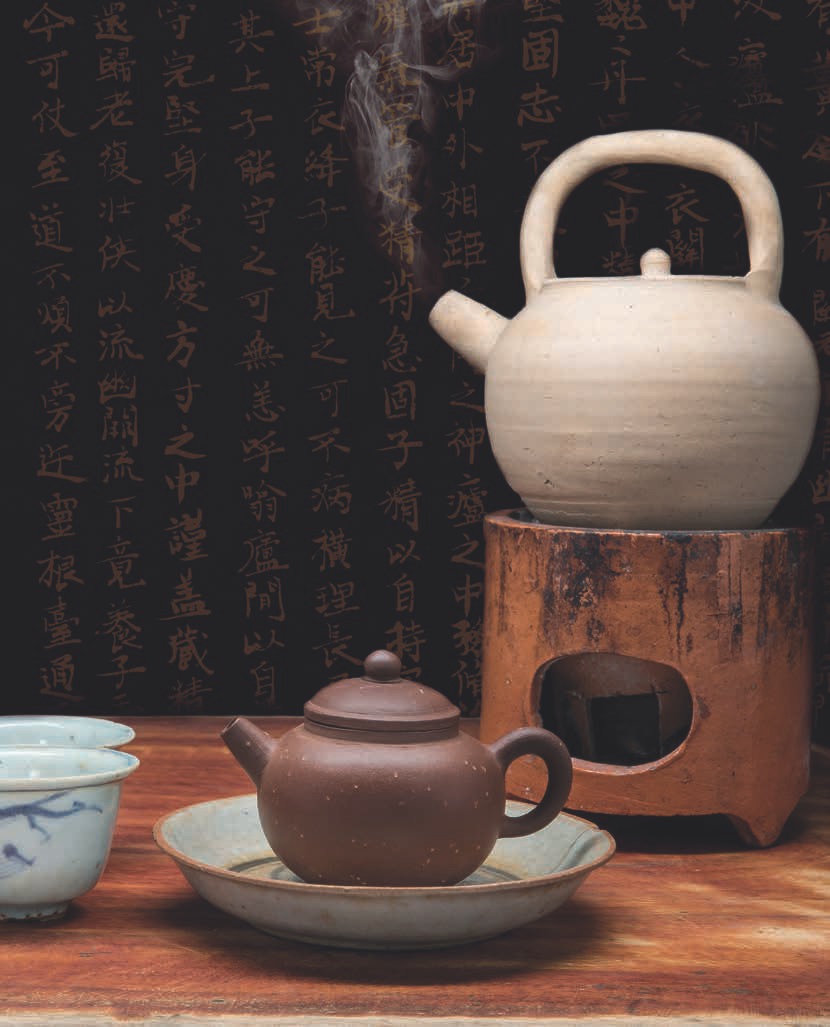

There really is something to the old saying "they don't make 'em like they used to." There is an elegance and sophistication that comes with sipping one's tea from a Qing or Ming Dynasty cup, brewing some old puerh in one's favorite Early Republic or Qing Dynasty Yixing or even just using a Ming bowl as a tea sink. Moreover, this kind of teaware is often a bit like aged and wise leaves, imbuing more energy to the teas we drink. Almost any tea drinker can tell the difference between modern and antique teaware, often from appearance alone. It is difficult to assess which factors make them antique, but it's not that hard to notice the difference they afford one's tea. Much of the reason why antique teaware works so much better is still a mystery.

I recently conducted an experiment while serving tea in the West by allowing some people, who had never before had the chance, to try using antique tea cups. About midway through a session of some excellent vintage puerh, I washed and passed a single Qing Dynasty cup around to everyone, letting each participant in turn try drinking from their "normal" modern cup and the Qing one at the same time. All of them testified to me that they couldn't believe the difference was so great - "noticeably so" being perhaps the most modest of their answers.

There are many possible factors that all contribute to the difference between antique and modern teaware, like the clay composition and processing, production and firing methodologies, etc. Perhaps another time we could talk about the effects of woodfired kilns on reduction, or the difference in clay processing that we know about when producing porcelain paste or Yixing stoneware; but for now, I'd like to discuss two more philosophical reasons why older teaware is better, both relating to the craftsmen themselves.

The first reason is to do with the changes in the modern world, and is not completely something we can correct in teaware production. We could, however, clean up the environment and return to a world where everyone eats organic food, has clean air and water, etc. Teaware makers were simple people back in the day, as they often are now. In fact, craftsmen in Asia rarely signed their name to their work, often putting the name of ancient masters they honored instead. But they did eat organic food, drank alcohol their neighbor fermented and also lived simply. They never went to school to learn extraneous information that was not directly used in their craft. From birth, they would have been devoted to teaware and apprenticed at a very early age, sweeping the floor, then helping with clay and finally starting to produce in their teens. Their whole life was devoted to teaware.

Nowadays, teaware makers are as complicated as anyone else in the world. They eat unhealthy, processed food that unsettles the heart. Their work is interrupted by cellphone calls, and they spend their formative years at school, straining to memorize data that has nothing to do with their craft, losing years of practice. Of course, this is not a black-and-white issue, as there are many positive aspects to schooling, including offering children more opportunities to explore careers different from their parents'. But the simplicity of life, the unspoiled character of the environment, and the lifelong devotion to teaware craft in those times is the first relevant reason that antique teaware is better.

The second important change that has happened in the teaware industry is that the producers themselves have stopped drinking tea. Without a deep understanding of the preparation of tea, it is very difficult to make nice teaware. And craftsmen today are not the "unknown craftsmen" of yesteryear; these days, everyone is striving earnestly to make a name for themselves. This inspires creativity and unique design, which is a good thing if it is coupled with an understanding of tea drinking. Otherwise, the desire to create new things without an understanding of their function results in lots of teaware that is completely aesthetic and very often dysfunctional. In Yixing, for example, it is not the art of crafting teapots that has been lost, but rather the relationship between the clay and tea liquor.

In the late 1980s, a teacher I know attended a large teapot convention in Yixing itself. Many famous master craftsmen were gathered there, including the Grand Master of a government factory. Many of these names would go on to make Yixing history, creating the artistic pots that would come to be worth the great fortunes that they are today. At the end of one speech, with all the artists as a panel, there began a question and answer session. The teacher I know stood up and politely asked, "For years now I have been trying to solve a mystery and I know that if anyone in the world can help me, it would be someone in this room. The stone ore mined to produce Yixing clay is billions of years old. For these long eons, it has rested beneath the mountain. What I can't figure out, therefore, is why the pots of the Qing Dynasty make tea so much better than the ones made today? Is it the way the clay is processed? Have secrets been lost?" One of the well-known artists responded, "Oh, but you're wrong. Our craft and skill is better than ever before. Now we have the science to break down the clays and analyze them, mixing and adding what we need. And we have electric kilns to reach the perfect temperature. The teapots back then were just teapots - now we make pieces of art!" Though this didn't help this teacher to find the answers he sought about Yixing clay, it did provide insight into another issue that affects all modern teaware.

This teacher realized that one important difference between these masters and their predecessors was that they didn't really love tea, and thus didn't understand its preparation. What the artist had said was true, and all the others on the panel had nodded in agreement: they had improved their precision in firing and their ability to create synthetic clays and mix natural ones in ways never dreamed of before. But, as the artist had himself said, they were making pieces of art - decoration - not teapots. The teacher I know felt differently. He felt that those old Qing pots were "just teapots," and perhaps that was a factor in why they not only make better tea, but appeal to him more, through their simplicity, even if the craftsmanship was more quaint and rough. Had function been sacrificed to form?

There were then, and continue to be, exceptions on both sides: the occasional modern teaware artist who understands tea, and antique artists who made pots for decoration, especially in the late Qing and Early Republic periods. Even today, in all aspects of teaware, I know artists who love tea and drink it every day. They understand a life of Tea, and strive to create pieces that not only function well in practical use, but fit into the aesthetic that develops as one progresses in Tea - Weng Ming Chuan's bamboo carving, Chen Qin Nan's kettles, Deng Ding Sou's teapots and Petr Novak's woodfired ware are all examples that quickly come to mind, though there are others who have also played a role in my own understanding of tea. However, for the most part, I turn to the craftsmen of yesteryear for all my teaware.

Taiwan has its own pottery city, called Yingge, and any tea lover living here of course is happy to frequent the city. It is wonderful on the weekends, as the old city is blocked off from cars and the cobblestone streets are full of pedestrians, food stalls and, of course, tons of shops with pottery and teaware. In meeting so many of these artists, both to buy teaware and to interview them professionally for Global Tea Hut and other magazines, I have come to the same conclusion of the aforementioned teacher: these days, so few of them actually love and drink tea, let alone understand it - despite the fact that they earn their living by, for the most part, making teaware. They try to create unique pieces aesthetically and distinguish themselves artistically, but since they don't really love tea and drink it every day, they can only cater to those who are either very casually into tea or looking for a piece more for its beauty than function. There is nothing wrong with that. Please don't misunderstand my point: while others may conclude from this that modern teaware makers are inferior, I do not share that assumption. I am merely helping to explain why antique teaware makes better tea than its modern counterpart. The aesthetic value of a piece, on the other hand, is relative to each of us, and there may be many people who prefer the newer ones, especially since the antiques are so much more expensive.

That said, you still can't help but wonder if something has been lost in the simplicity of teaware being made by tea lovers - those who love and drink tea every day, and have learned how to prepare it. Sometimes, something is so obviously missing from a tea set you wonder how it could have been missed. But then, you're a tea drinker. Years later, you find the very thing you were looking for and when you investigate, you find out that the artist is a tea lover like you and came to the same obvious conclusion that you did about the practicality of such a piece.

Using Weng Ming Chuan, the famous bamboo artist who carves gorgeous tea utensils, as an example might illustrate this point better. For years I wondered why all the tea scoops and other utensils, while beautiful, were covered in stains, paints and lacquers. It seemed obvious to me, and most tea drinkers in my circle, that we wouldn't want such chemicals dipping into our tea leaves - too obvious. I saw some tea drinkers solve this by using sticks or stalks of bamboo from their gardens as spout cleaners and flat pieces of natural wood for scoops - brushing the tea leaves into the pot, rather than scooping or pouring them. Then I met Weng Ming Chuan, and found that he had come to the same conclusion years ago and started carving bamboo utensils without any chemicals as a result. He even came up with a method of staining the pieces with red tea when he desires a darker color.

If the independent artists who make teaware have lost the love for tea, which then inspires one to begin learning how to brew tea and how to live a tea life, what could be said for factory production? Back in the day, even the factories that made pots and cups were full of simple potters who drank tea themselves and loved it, let alone the masters who designed the production lines where teaware was produced. There may have been exceptions, but for the most part, they were tea lovers and understood tea preparation. Today, when a porcelain factory designs cups, as well as the paste that will be used to manufacture them, they consider factors like beauty and cost efficiency, rather than focusing on how the shape will affect the tea liquor or how the different minerals in the paste will affect the Qi of the tea. The same could be said for Yixing pots, as so many potters are busy trying to make a pot shaped like a baseball or a dog, rather than one that pours properly and influences the tea leaves in the way that married Yixing clay to tea so long ago.

About ten years ago, another of my teachers initiated a program to fix some of this. He himself has since then been traveling to Yixing five to six times a year to teach a small group of potters who are interested. Of course, he's not teaching them how to make pots, as they could obviously educate him in that regard; but rather, having found that they truly do love tea and wish to learn, he is teaching them how to prepare tea. Just by loving tea and learning about all the factors that make a better cup, they are progressing to the point at which their own inherent creativity will produce teaware made for tea preparation.

There is no denying that aesthetics play a role in tea preparation. I myself have written that it is often okay to choose a piece that functions a bit worse if it is aesthetically pleasing to you. This will affect the most important aspect of any tea session, which is not the leaves or teaware, but the people. This is also why restaurants spend as much on ambience as they do on the menu. However, we can never completely sacrifice function for beauty if we are to truly appreciate the tea leaves. If the teaware is a piece of art in and of itself, that is fine. But if, on the other hand, it is intended to make tea, then it must be judged mostly, or completely, on its ability to function in that regard.

In the end, there is a solution for those with initiative. We can encourage the artists who are interested in tea to explore tea preparation and apply their wonderfully creative skills to the development of pieces that are unique in function and form. Also, even those artists or factories who have profit as a bottom line still respond to what is ordered by their customers, and can often be convinced to create new production lines or adapt old ones to fit the needs of tea lovers. In the end, nice teaware produced in this era will come through teaware makers who love drinking tea and understand the ins and outs of the brewing process. We may not be able to return to a healthy environment, free from distractions, where craftsmen can devote their whole lives to teaware; but we can inspire a love of tea and tea-drinking that will bring spirit and function back to the teaware industry.

The love of tea explains why my master makes better tea than I do. For a long time, I thought it was technique, but when I asked him, he'd always answer that he "just loved tea." Slowly, over time, I grew to understand that it was that simple. This applies to teaware as well, and helps, in part, to explain the difference between modern and antique pots, cups and utensils. When you love tea, you love the vessel it's prepared in, and you know that after you've created the piece, some tea lover will take it home and appreciate it as you have, as much for its beauty as for its ability to improve his or her tea. I personally always hope that it will be thus with my paintings - that they will help inspire some tea space, somewhere. And as I grow in my understanding of Tea, life and a life of Tea, I more and more find my sense of beauty in the simplicity of function - a teapot for tea, leaves and water.