|

|

Stepping into the tea forest kingdom of Yunnan, we find puerh-growing areas primarily scattered throughout the Hengduan mountain range near the Lancang and Nujiang rivers and farther to the south. Along the lower reaches of the Nujiang, in the southwest of Yunnan, near the border with Myanmar, in addition to the beautiful and world-famous jade of Ruili, Dehong tea trees provide another type of green gem, glowing and shimmering in the spring breeze.

"Dehong (德宏)" is transliterated to Chinese from the Dai language. "De (德)" means beneath, while "Hong (宏)" refers to the Nujiang River. Together the meaning is: "Area on the Lower Reaches of the Nujiang." The Dehong Dai and Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture is one of Yunnan's eight ethnic minority autonomous regions. Jurisdiction over the administrative district has changed many times. In 2005, the prefecture's capital was established in Mangshi, with Ruili as the secondary city and three counties of Longchuan, Yingjiang and Lianghe. Covering an area of 11,526 square kilometers, the prefecture is inhabited by numerous ethnic groups, including the Dai, Jingpo, Achang, De'ang, Lisu, Wa and Han people. Dehong has been inhabited for more than 5,000 years. In ancient times, it was known as the "Dianyue Elephant Riding Kingdom," due to the many wild elephants that roamed the forests.

Dehong has been a natural paradise since primordial times - long before there were human eyes and hearts to enjoy its beauty. And locals have lived tea lives going back further than any calendar can reach. More than 4,000 years ago, ancestors of today's De'ang ethnic group, the Pu, picked, processed and consumed tea leaves in sacred ceremonies, offered as prayers and also enjoyed as medicine and hospitality for visiting guests. Later, they planted tea gardens, and Dehong still contains numerous hundred- and thousand-year-old tea trees and tea gardens that were planted mostly by ancestors of the De'ang ethnic group. Consequently, historians refer to the De'ang people as "China's ancient tea farmers."

The De'ang believe that they are descended from Tea, honoring and praying to guardian Tea spirits, like most aboriginals in Yunnan. There is also some folklore suggesting that the creation myth of the De'ang is a world born out of a tea tree. This is a testament to the people's deep and ancient relationship to tea that has become central to their life, culture and worldview.

The tea culture and tea production techniques of various Dehong ethnic groups were highly developed and widely propagated. Historical records recount that members of the Dai and Bai ethnic groups engaged in mutual trade of fabrics, tea and salt during the Yuan Dynasty period (1279 - 1368). Nandian tea (南甸茶), which we will explore in more detail later on, was produced during this period. During the Ming (1368 - 1644) and Qing (1644 - 1911) dynasties, Dehong produced Jinchi tea (金齒茶), that is, today's bamboo tube tea (Zhutong tea, 竹筒茶), as well as other tea products, such as Gu (沽茶) and Yan tea (醃茶, not to be confused with Cliff Tea), which we will also discuss later on in our journey.

The Dehong tea industry continued to develop to its present state. During the 1940s, the then-director of the Lianghe County Administrative Bureau, Feng Weide (封維德), wrote An Elementary Introduction to Tea Growing (種茶淺說). It describes techniques for planting, managing and harvesting tea, and provides the first written description of close-planted tea plantation production in Yunnan. By the 1960s, Lianghe County's Dachang Tea Factory began producing Moguo tea (磨鍋茶) that initiated the wave of Yunnan roasted green teas that were popular throughout the later half of the twentieth century.

As we can see, Dehong has a long and rich history of growing, producing and consuming tea (the De'ang still eat tea leaves, as we will discuss later on in this article). It is culturally one of the richest regions of Yunnan, and no pilgrimage to the birthplace of tea, "South of the Clouds," would be complete without a stop here.

In historical terms, culture develops from geography. Dehong is located in the western part of Yunnan, along the southern foothills of the Gaoligong Mountains, and, aside from Lianghe County, the entire prefecture lies along an international border. This border extends for 500 kilometers throughout the prefecture, with 24 towns and more than 600 villages bordering Myanmar. Dehong is a southwestern border region agricultural prefecture. During the late Qing Dynasty and early Republic of China period, China found itself gripped in the turmoil of war, and frontier defenses were allowed to slip into disarray. Consequently, opium/ poppy cultivation was rampant, and tea trees were chopped down throughout the region. The tea industry of Dehong was devastated. These factors combined with slash-and-burn agriculture caused many tea gardens to become "wild tea." As a result, nearly all surviving tea trees are found in the high mountains. By 1950, only some 410 mu (畝, 1 mu = 1/6 acre) of tea gardens remained. As we survey the geography and history of Dehong, we can also learn from the negative decisions that have resulted in environmental degradation, as well as the positive shifts that have begun in the modern era to try to correct this course. In this way, this journey through Dehong will have the potential to change Dehong itself!

We traveled to Dehong in the spring, to see the wild tea-growing areas firsthand. We drove from Mangshi to the village of Daxiangshu near Fengping. On this three-hour-plus drive, we passed mountain after mountain as the road circled around the lofty peaks. The long, dusty mountain road seemed endless. After finally arriving at our destination, we still had to hike another half-hour before we came upon the wild tea trees stretching upward into the sunlight. Beneath our feet, the winding hillside path was covered in a thick layer of fallen leaves. To our left, we saw the sloping hillside, filled with an endless sea of branches waving bright green leaves. To our right, we could see mountains and valleys sprawling beneath us - the tea trees fluttered in the spring breeze amidst the forest greenery and blue sky. A tea tree poked out beside a cardamom tree, while another was growing right up against a banyan tree. Such sights inspire a Chajin, filling the heart with a free and glorious sensation that lingers on, drawing us back here in spirit when we sit at home much later, sipping our spoils from such a lovely trip and reminiscing about all the wonderful places in Dehong we've visited. Such trees make an impression on the heart!

Some of these lucky tea trees are large and several hundred years old. Others are several decades old and are wild, propagated naturally from the seeds of the nearby large trees. These trees of different generations all grow together. Some trees have very large leaves, while some others have very slender leaves and branches. One thing they all have in common, however, is that the very few young tea buds are very difficult to pick. Aboriginals are therefore very skilled climbers, often placing a board leaning up against the first fork in the tree and running up the plank to get into the tree with the ease and grace of someone long accustomed to climbing and foraging in the forest. Most of these tea-growing areas survive as mixed tea forests. The trees were long ago individually planted and can be considered first-generation Yunnan tea gardens, the categorization of which we shall discuss in the coming pages.

What is a so-called "second-generation" tea garden? Yunnan contains the largest number of preserved wild tea trees and ancient tea gardens in China and the entire world. These growing areas contribute to the diversity of Yunnanese tea. The defining characteristics and development of Yunnan's more than four million mu (1 mu = 1/6 acre) of tea gardens are the result of a combination of factors, starting from the time that humankind first discovered and began to utilize tea, and influenced by the historical backdrop of various time periods, as well as different tea tree domestication and cultivation characteristics over time.

There is no standard way of classifying tea gardens in Yunnan. Some agricultural specialists classify the tea tree resources and tea gardens/plantations of Yunnan into two distinct types: first- and second-generation gardens. I would add to this a third and fourth "generation" or "wave" of tea production. These later two types of tea cultivation move away from what could be called a "garden," and into what should technically be referred to as a "plantation," with a focus on greater density of trees, increased yield and a commercial approach to tea production. However, as we shall soon discuss, secondgeneration gardens are, in many ways, a phase between the first-generation gardens, which were only for tribal use, and third-generation plantations, since they weren't yet large scale enough to be called "plantations," but were commercial.

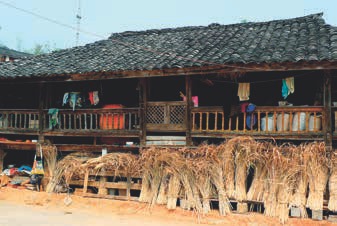

Yunnan's first-generation tea gardens are based on the oldest type of tea garden model. They contain five- to six-hundred-year-old tea trees, which local farmers used to create a surrounding fence of trees. These gardens were structured as several dozen tea trees planted deep in the forest, in front of and behind the house or surrounding the farmers' cultivated land. It is important to remember that these villages were more remote than they are today. They were generally located deep in the mountains, and the forest was only ever a stone's throw away from any house in the village.

The few trees surviving to this day now stand as village landmarks or guardian spirits. This type of landscape can be seen in all the major tea-growing areas of Yunnan. Within Dehong, these exalted tea trees can be seen near village houses in various places, including Luxi, Ruili and Lianghe. An example is the large cultivated tea tree discovered by a survey in 2003, which is located beside a river in the village of Xianrendong in Luxi's Jiangdong Township. A Dali tea variety, the tree is 1,800 years old and more than 27 feet tall, with a 2.5 feet base diameter. Another such tree was discovered in 1999 in the Longchuan County, Huguo Township village of Laokong. This tree is 800 years old, more than 30 feet tall, and has a 2.8 feet base diameter. Yet another large cultivated tea tree was discovered in 1981 in Lianghe County, Mengyang Township, Kazi Baimatou village. This tree is also approximately 800 years old with a height of nearly 20 feet and a 2.6 feet base diameter.

Although these ancient tea trees were not grown in plantations, they were grown for tribal cultivation. The leaves were used in sacred ceremonies and prayers, for healing and spiritual communion with Nature, as well as in hospitality offerings to visiting guests. Even in more modern times, the market value of these trees was never very high. As tea prices have risen in the last few years, however, tea sellers have begun to seek out these teas for their unique characteristics, rarity and growth as single solitary trees. This has led to several issues in the puerh market, including the unfortunate death of some such trees due to over-harvesting.

This oldest form of tea cultivation is based on "single tree cultivation" or mixed planting with other forest trees like camphor and/or flowering trees, which have grown together and are preserved to this day. The aboriginals knew that nearby trees, plants and biodiversity influenced the health of the tree and the characteristics of the tea as well. True first-generation tea gardens make up less than 2% of the total tea-growing area in Yunnan.

Yunnan's second-generation tea gardens are also the result of their historical context. Profit derived from international trade directly led to largescale tea production, changing the face of tea production in Yunnan. Trade between China and Europe steadily increased throughout the nineteenth century. Europeans particulary favored Chinese tea and silk. In 1886, the Chinese tea trade accounted for 95% of the volume of tea sold throughout the world. The Qing Dynasty government vigorously promoted tea production, in order to purchase large quantities of weaponry and pay off the vast national debt. Around 1900, the throne approved the establishment of French and English customs offices in the Yunnan city of Simao. (Now renamed by its aboriginal name "Puerh," which is where the tea gets its name, since it all went to this city for market sale to the rest of China and was therefore "tea from Puerh.") This greatly stimulated tea production in the surrounding areas and solidified Simao's position as the number one tea-producing county in Yunnan. According to customs statistics, the value of tea exported from Simao between 1912 and 1923 exceeded 110,000 taels of silver. Demand for tea continuously increased, as did the need for funds to support the fragile Chinese economy. Consequently, the natural or half-natural production model of Yunnan tea was destroyed, as the tea industry entered an era of commodity production and second-generation tea gardens began to appear.

Second-generation tea gardens are commonly referred to as "Man Tian Xing (滿天星, "Star-filled Sky")" tea gardens. These gardens are dispersed throughout the various major tea-growing areas of Yunnan and comprise approximately 5% of the tea gardens in the province. Tea gardens of this stage are characterized as follows: most were planted during the late Qing Dynasty (1644 - 1911) through the Republic of China period (1912 - 1949); trees are primarily between 70 and 120 years old; garden composition is relatively uniform; trees are primarily Yunnan large-leaf varieties; trees were planted in groups, following the mountain slope; the planting density was low, which provided excellent space for tea growth; the trees enjoyed outstanding topographical conditions and fertile soil; and trees were planted near villages, which allowed for convenient supervision and harvesting. Dehong is a rich and biodiverse area with the potential for outstanding tea production.

Offering free tea - such thoughtfulness! This was a common sight in the small towns and villages of China and Taiwan during bygone agricultural days. Nothing captures the spirit of tea as well as offering free roadside tea! People would leave a jar or large pot with some bowls by their house, at the outskirts of the village or even on well-traveled roads for passersby to refresh themselves. What courtesy! What hospitality! Imagine someone walking a kilometer or two twice a week to wash the pot or jar and bowls, and replace the tea with fresh leaves and water. And they did all of this for people they may never have met! They were sharing and giving without thanks.

This takes us back to another time, when neighbors loved each other as family. There is a lovely Chinese saying, which is "One-house people shouldn't talk like two-house folk. (一家人不說兩家的事)."

This is a way of saying, "Don't be so formal, we are family!" Finding a place where people still take the time to refresh strangers, help and love each other and honor one another as one people is rewarding in the modern world. It should come as no surprise that such a place is one filled with tea spirit, or that tea is the medium of this hospitality. We were so inspired to find this dying tradition alive in Dehong. We found free tea offerings when we came to a small village in some township of Luxi City, Dehong prefecture, Yunnan. We found it at a mountaintop bus stop, served in traditional pottery. Again, in a different mountainous area, we found it at a village intersection, using modern concrete paint buckets to hold the water. Have you had anything to drink? That taste of cool tea was extremely refreshing. Even though I don't know you, I must say thanks.

China contains many different ethnic minority groups, and Yunnan Province alone contains the most. On average, one in every three residents of Yunnan belongs to an ethnic minority group. Each of these groups possesses its own unique food culture: the De'ang people enjoy drinking tea; the Dai people prefer sour flavors; the Hani favor raw foods and salads; while the Jingpo people are known for their preserved and pickled foods. A rich ethnic tapestry gives rise to a rich variety of food cultures in Yunnan.

Dehong's tea industry began to develop rapidly following the Communist Revolution, with the first wave of growth occurring between 1950 and 1966. This is the beginning of what could be called the "third-generation" tea plantations, with a shift from "garden" to "plantation" cultivation methods.

Tea plantations increased in area from some 400 mu to more than 30,000. And this was just the first stage of growth! The next wave, which occurred between 1977 and 1990, brought an increase in the area of the prefecture covered in tea plantations to over 160,000 mu. Tea growing became an important means by which rural people could escape from poverty.

The fourth "wave" or "generation" of tea cultivation in Dehong, and Yunnan, is much more modern. It follows the rise in interest in organic products. With an ever increasing market demand for organic products, organic tea plantations have begun to rise in importance. We will discuss this shift to fourth-generation tea plantations and the relevance of organic farming after a bit more historical exploration of third-generation plantations.

After the Communist Revolution in 1950, the government of Dehong vigorously promoted wave after wave of growth in tea production, to replace opium farming as a solution to its predicament as a frontier agricultural prefecture. At the time, the Lianghe County Administrative Bureau issued a communiqué regarding a total ban on opium and switch to tea growing. It further arranged for the transport from Tengchong of eighteen "packs" of tea plants (roughly 1,350 kg), which were then distributed to each of its administrative areas for planting, that is, today's Luxi County Jiangdong Township, Longchuan County Wangzishu Township, and Yingjiang County Yousongling Township. The government vigorously promoted tea as a replacement for opium, which consequently led to the promotion of new tea growing techniques and methodologies.

As a result, tea production gradually increased. By 1954, opium/poppy growing was prohibited in all mountain areas of the prefecture. The government began providing subsidies to further encourage tea production. For example, the government provided subsidies for new tea plantation construction, sent tea plants without charging for seeds or transport, offered rice in exchange for planting tea trees (for each 1,000 tea seeds planted, farmers received 500 g of rice) and gave each resident who worked on the tea plantations 1 RMB and 500 g of rice per day of labor. These concrete benefits allowed tea growing to rapidly overtake opium throughout Dehong Prefecture, as new tea plantations began to stretch across the countryside. By 1957, the total area of Dehong's tea plantations reached 8,000 mu, which represents a 20-fold increase in only eight years!

Later, during China's "Great Leap Forward" (1958 - 1961), the government promoted a new slogan: "Step out the door and see a tea mountain, step in the door and see a tea factory. The roaring sound of machinery will bring 10,000 years of good fortune." The government sent agricultural scientists and technicians to mountain areas to provide guidance at the local level. By 1966, the prefecture's tea plantations had, like the Great Leap Forward slogan, grown to an area of more than 30,000 mu. This was Dehong's first phase of rapid tea expansion.

The tea trees planted in this stage were primarily Yunnan large-leaf varieties from Changning, Fengqing and other areas. The planting technique was based on "tree to tree, following the mountain slope" grouped planting. According to Lu Yu's Tea Sutra: "The planting method is like that used in growing melons." In other words, the planting density is low. These cultivation methods are characteristic of Yunnan's second-generation tea plantations.

These tea-growing methods could be seen in other areas of Yunnan at the end of the Qing Dynasty and during the Republic of China period, but by the end of the 1950s, these areas had already progressed to third-generation tea plantation methodologies, that is, contour-strip farming ("taidi cha," 台地茶), which is proper industrial, environmentally un-friendly agriculture. During our trip to Dehong, the prefectural government provided materials which indicating that Dehong's tea growing methodologies prior to 1976 were still based on the second-generation "tree to tree, following the mountain slope" principles. Perhaps due to Dehong's remote location, its agricultural policies and techniques were unable to keep up with those in other areas.

Why have I chosen to emphasize the stages of cultivation techniques and tea plantation development? I have chosen to do this primarily because growing techniques affect later tea tree development. Puerh quality is greatly determined by its environment: the mountain/region it comes from, type of garden and age of tree(s). In terms of raw tea materials used to make puerh tea, ancient trees are preferable to old trees, and old trees are better than small trees. Today, this is common knowledge. Tea trees are called "ancient," "old," and "small" based on their age, but growing techniques and planting density also directly affect the quality of the tea leaves used to produce puerh.

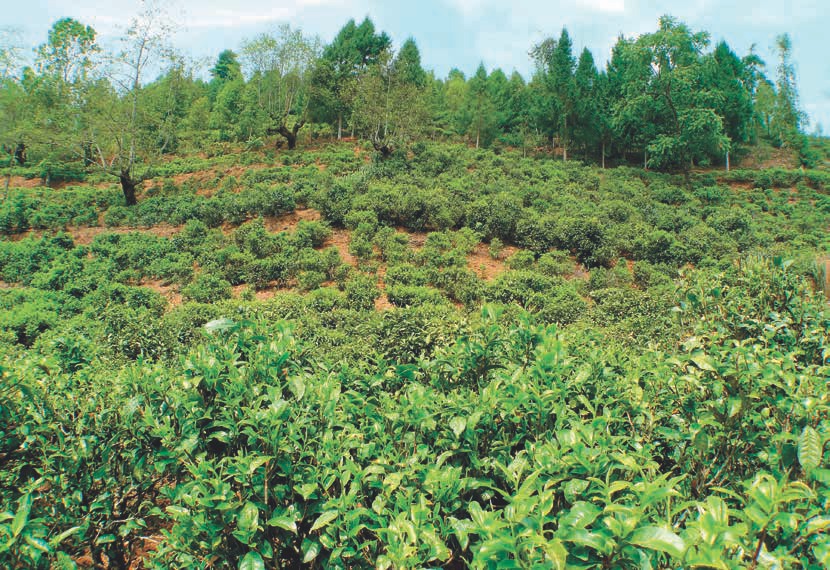

Ancient tree tea and wild tea are grown in biodiverse forests. Tea trees in first- and second-generation tea gardens (which are called "eco-arboreal" in this magazine) are planted in low density, with several feet of separation between the trees. This provides the trees with excellent growing space, and the several types of tea gardens/plantations described above provide Dehong tea producers with excellent leaves for puerh tea production. However, the third-generation plantations, if created in a way that strips the natural contour of the mountain and accompanied by agrochemicals, does not result in quality tea. The quality of puerh and dian hong is defined almost exclusivly by its terroir, so if the environment is not biodiverse and rich, the resulting tea will also lack depth and character.

The Dehong tea industry development did not escape the effects of China's Cultural Revolution. This period's slogan was "Take grain as the key link to ensure all-around development." Tea trees were destroyed to make way for farming of food grains. Between 1968 and 1975, tea plantations experienced negative growth for the first time since the Communist Revolution in 1949.

As we mentioned earlier, after 1977, tea production in Dehong entered its second wave of rapid growth. The government intensively promoted tea production by providing subsidies and creating model tea plantations, establishing standardized tea plantations in more than 400 locations. Tea production once again entered a period of rapid development, and, by 1990, tea plantations in Dehong covered an area greater than 160,000 mu. Tea growing had become an important aspect of the agricultural economy and a means for rural residents to escape from poverty. By using new cultivation techniques and selecting Yunnan largeleaf tea varieties, economic prosperity came to villages of Dehong, such as Luxi's Hetou and Daopo, Longchuan's Wangzishu Xiaoniu lower village and Mangshi's Huaqiao farm.

Tea cultivation during this period was based on "level strips and close bush planting," which is characteristic of Yunnan's third-generation tea plantations. These plantations are characterized by planting perpendicular to the slope with level arrangement of trees, and the tea varieties are dominated by seedling families of Yunnan large-leaf teas. Third-generation tea plantations formed the mainstay of Yunnan's tea industry and were extensively promoted throughout the tea-growing regions of the province. Operation of these tea plantations is characterized by intensive use of land, technology and capital. Because the tea trees are primarily between 30 and 40 years old, they are in their prime growing years and satisfy the objectives of early investment, early yield and early profit - all of which are quality-killers.

On this trip to Dehong, we continuously passed these third-generation tea plantations growing in the lowlands and as a green carpet covering the hillsides as we drove through the outskirts of Mangshi.

The environment of a place gives rise to its industry. Yunnan is the birthplace of tea. Yunnanese red tea (dian hong, 滇紅) made its way throughout the world beginning in the 1930s. Specifically, in 1938 the first batch of Yunnan red tea was shipped through Hong Kong to London and achieved instant fame, selling for high prices. Fengqing, Mengku, Menghai and other Yunnan tea-growing areas began producing large quantities of red tea. Crushed red tea sold in teabags is the highest-selling tea in the world, making up approximately 90% of tea sales worldwide. Yunnan large-leaf tea varieties also provide tea for this market.

Red tea production came to Dehong in 1974 and is primarily focused on gongfu red tea, which is also known as "congou" tea in the West (see this year's June issue of Global Tea Hut, which is all about gongfu red tea); crushed teabag tea; and red pearl tea. Because the international market for crushed red tea is so large and Dehong's third-generation tea plantations are focused on high yield and high profit, most tea plantations produce tea for mass-market red tea sales. Unfortunately, this type of agriculture decreases the quality of tea, and, worse yet, harms the environment and health of the farmers. Ending unsustainable agriculture is a goal that all tea lovers worldwide should be striving to achieve together!

After the 1990s, Dehong's tea industry entered an era of stable growth. With the dawn of the 21st century, the trend in agriculture toward production of environmentally friendly natural food products has become clear. This has led to a rise in natural tea growing techniques and organic tea plantations. According to statistics, in 2004, Dehong contained 889 mu of tea-growing areas that were certified as organic by the Organic Tea Research and Development Center (China). By 2005, the tea plantations in Dehong with China Green Food Development Centre (CGFDC) "Green Food" certification covered an area of 18,000 mu. Recently, these number have grown, with more than 1,000 mu of organic tea flourishing in Dehong.

These are fourth-generation tea plantations. Organic tea plantations are based on the following ideas: conformance to organic agricultural requirements, cultivation based on organic farming techniques and coordination with the natural ecology, and allowing the growing environment to maintain stability and long-term health. Farmers do not use chemical fertilizers, pesticides or genetically modified plant varieties. Certified organic tea plantations form the primary direction and objective of tea plantation growth today and into the future. This example should inform all tea production, and not just in Dehong, or even Yunnan, but throughout the world. There is no need for unsustainable agriculture that is profit driven and without long-term scope or a perspective that includes the health of the local environment, the farmers who cultivate the land and the long-term health adversities of those who consume such tea. Hopefully, Dehong wil continue changing!

Famous Historical Teas

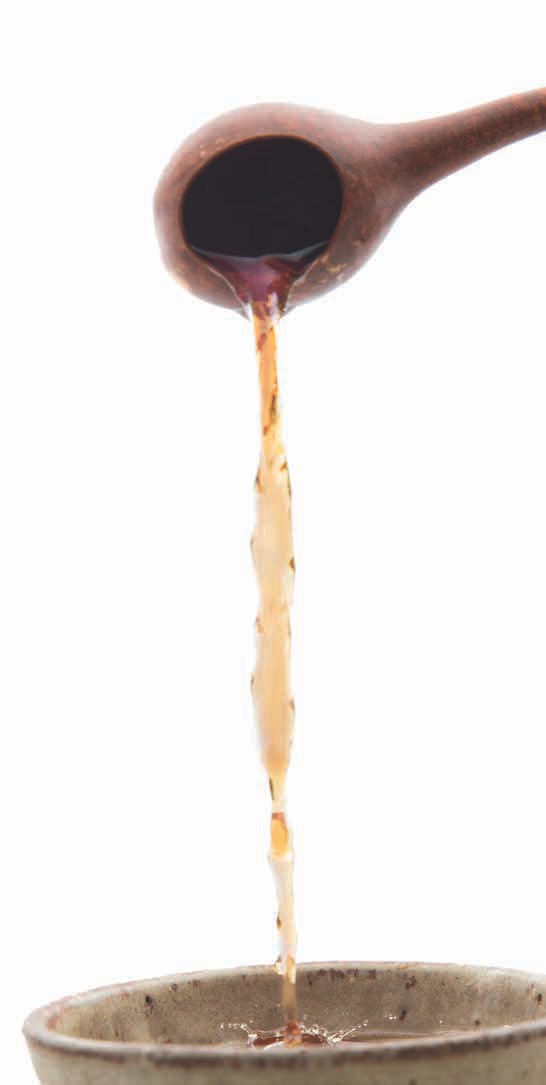

Nandian tea (南甸茶) from the Yuan Dynasty (1279 - 1368): Historical records describe this tea. It was produced through heat processing using boiling water, and then sealed, pressed and fermented.

Gu tea (沽茶): This tea was used by various ethnic groups of Dehong when entertaining guests. According to the Baiyi Zhuan (百夷傳, literally, the "Account of One Hundred Barbarians"), Gu tea was produced as follows: "In the spring and summer, they pick and then boil the leaves of mountain tea trees. They then seal the leaves in tubes of bamboo. After one or two years, they remove and prepare the leaves."

Jinchi tea (金齒茶): During the nineteenth year of the Wanli Era (ca. 1591), of the Ming Dynasty (1368 - 1644), Huang Yizheng's Shiwu Ganzhu (事物紺珠) listed this as a type of tea. It is named for its origin during the Yuan Dynasty (1271 - 1368) in areas under the control of the "Jinchi Guard," a region that includes today's Baoshan and Dehong. Jinchi tea processing includes both shai qing (曬青, sun-drying) and bamboo tea. It was produced by boiling freshly picked tea leaves, rubbing them in the hands, and then either sun-roasting or packing and roasting the tea in bamboo.

Yan tea (醃茶): This ancient edible tea was produced by the De'ang people. Because of its slightly sour flavor, it is also known as "sour tea." It is produced by picking young tea buds, which, after boiling and air-drying, are packed in palm tree leaves and placed in a pit located somewhere high and dry. The hole is filled in with soil to a level higher than the surrounding ground and then covered with palm tree leaves. The leaves are then covered with rocks to prevent water from seeping into the hole and ruining the tea. After a certain period of time, the tea is dug up and eaten. It can be eaten with seasoning, such as salt, nuts, chilies and ginger or chewed by itself.

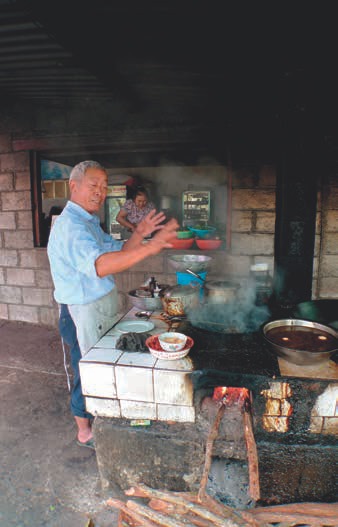

As the season turns to Spring, the buds on the tea trees flutter in the wind, beckoning tea lovers such as ourselves to step into the mountains and taste their flavor and drink in the spirit of this season and place. Traveling through these mountains to seek out tea was the primary purpose of our trip. Yunnan is a place of many ethnic groups and even more cultures. Beyond the mountains lie even more mountains. We observed various everyday activities in their pure and natural surroundings. Although amateurs, we took photographs whenever the opportunity presented itself, hoping to preserve these fleeting, precious moments.