|

|

Understanding the importance of Yixingware is a great place to start steeping in the depth of this amazing art. No teaware has held such a long-standing and profound relationship to tea as Yixingware. There is a tremendously vast heritage of skill that goes into producing Yixingware, spanning many disciplines and centuries, and an equally rich culture on the side of Chajin. Let's explore the reasons why!

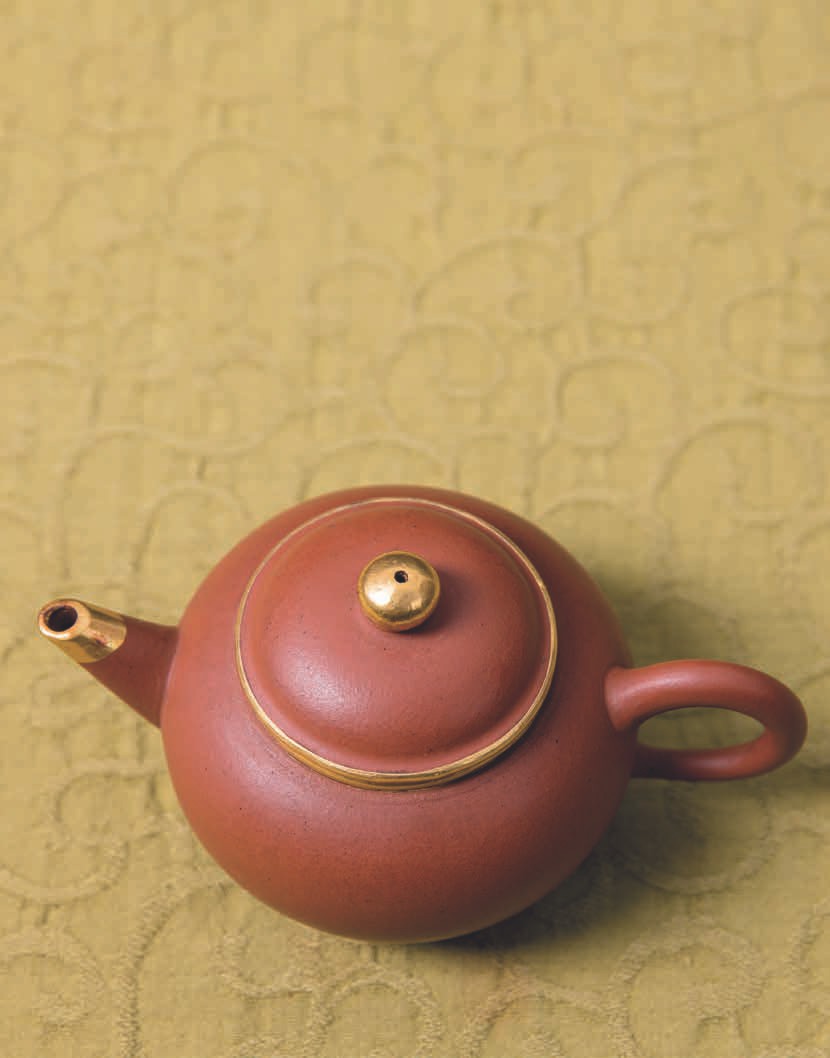

There is no other ceramic art quite like Yixing teaware. Its birth coincided with a historic change in Chinese tea culture, when brewing teas in powdered form was replaced by whole leaves. A new kind of pot was required, and the lovers of tea, even centuries ago, wanted something that would enhance their tea in flavor and beauty. Purple-sand clay pots from the now-legendary town of Yixing would find a way to satisfy tea lovers on both these levels of appreciation. In fact, finding a way to balance the elegance and utility of a teapot would become the very standard against which teapots would be weighed and valued. Few other kinds of ceramic art have perfected this juxtaposition of the practical and aesthetic; and few genres of ceramic art have reached such a profound depth and complexity of clay processing, craftsmanship, style and functional design. Furthermore, Yixing teaware has always been enjoyed by people from the whole spectrum of social classes. The court used elegant Yixing pots to brew its tribute teas; and then, like today, one could stroll down the city streets of China, Hong Kong, Taiwan or other places where Chinese live, and see groups of people sitting around, pouring tea from these small pots. The legacy of Yixing has, in many ways, become part of the story of tea itself, and their marriage is as perfect as any could be. Many Chinese tea lovers would find it hard to imagine a great tea without an Yixing pot to steep it in.

Some tea drinkers view teapots as nothing more than a vessel in which to steep tea, and yet, even these more practical people will find enjoyment in the world of Yixing. One of my favorite experiments is to brew the same tea, in the same amount, using the same water temperature, but in several different kinds of teapots: a polycarbonate teapot, glass teapot and an Yixing teapot, for example. On two separate occasions, I conducted this very experiment for a teahouse staff in Houston, as part of their training. More than 80% of the people found the tea brewed in the Yixing teapot to have a better flavor and aroma. Even in function alone, Yixing teaware has made a permanent mark on the history of tea culture.

Drinking tea has always been an integral part of life in China. In ancient times, before the Tang Dynasty (618 - 907), tea was predominantly thought of as a medicinal beverage. It was a part of the herbal pharmacopeia of healers. In other places, tea was simply a thirst-quenching beverage, or even a kind of dietary supplement or vegetable drink. It was sometime between the Tang and Song (960 - 1279) dynasties that tea grew into a kind of cultural art. Before then, there was no special teaware designed to enhance the consumption of tea. However, during the Tang Dynasty, tea drinking started to become popular among scholars, Buddhist monks and Daoist priests. This new spiritual and aesthetic approach to tea would lead to a refinement of the process, including the whole practice of making tea powder and its complicated brewing. New kinds of teaware, such as wheel grinders to grind the tea into powder, bamboo sieves, storage containers and tea bowls started to appear. Song Dynasty tea culture would then continue to cultivate the same tea method, improving techniques and even the artistic quality of the various accoutrements used in the tea ceremony that had started in the Tang Dynasty.

Sometime during the Ming Dynasty (1368 - 1644), tea art would, in most ways, reach its modern expression - using whole leaves steeped in ceramic teapots. Realizing that too much effort and domestic labor was being wasted on the production of powdered teas to satisfy the need of government officers and royalty, the emperor abolished the tradition of making tribute tea cakes from powder in 1391. He further forbade production of any compressed cakes and changed the powdered tea culture of the previous dynasties to whole tea leaves. Consequently, all the teaware formerly used to prepare powdered teas quickly became obsolete. This revolution in tea culture would make Chinese craftsmen and artisans reconsider teaware, focusing now on the creation of teapots in which to steep tea leaves.

The earliest record of teaware production in Yixing (formerly called Yan Xian) can be traced to the Song Dynasty. Early potters in Yixing used the skills they had learned from making household wares such as urns and vases to begin making teapots. It was not until the period of the Ming Emperor Zheng De (1505 - 1521) that Yixing teapots were elevated into an art form. Most histories relate this proliferation to the celebrated figure of Gong Chun. Gong Chun was the humble servant of a government officer, so little is known about his background. Many versions of the story tell of a business trip he took with his master. Along the way, he met an old monk in Jin Sha Temple. The monk was also a potter, crafting teapots for the tea he drank. Gong Chun was intrigued by the way the monk refined the clays and made such "admirable teapots." He used all his spare time to learn from the monk, and made teapots by hollowing out a glob of clay with a spoon, and then using his bare hands to form the shape of the pot. One day, his master saw his work and liked it so much that he asked Gong Chun to make several more. He gave them to his friends. Within a few years, his works were so famous that he finally left his master and earned a living just by producing teapots. Gong Chun's work, and financial success, inspired other local potters in Yixing. More and more teapots of different shapes, clay compositions and sizes were produced, and a fashion of collecting quickly formed among the upper class and literati.

Much of what makes Yixing teaware so special lies in the constitution of the unique clay ore that is mined there. Many kinds of ore are found in Yixing, and all of them have the unique characteristic of being completely lead-free, which allows potters to make unglazed pots that can be used for daily consumption. Unglazed clay offers a porous surface that can absorb the flavor of tea over time, a process collectors call "seasoning" the teapot. The spectrum of colors and composition available in Yixing ore is amazing. Yixing is truly blessed to have these various types of clay, all of which are nonpareil in their superb workability, refined texture and naturally beautiful colors. Clays with a low shrinkage rate, such as zisha and duanni, allow the potters' imagination to run wild, crafting teapots of different sizes, shapes and styles, but with the same precision that generations of skill have honed. Clays with a very high shrinkage rate, such as zhuni, produce teapots of relatively small size and simple shape, but with such ravishingly soft and jade-like texture that they are often the most valuable. Without these special clays, Yixing teaware would never have reached such a noble and distinctive status. In Yixing, "clay master" and "master potter" have always been different professions. Although a master potter may enjoy more fame and wealth, a clay master is always regarded with the highest esteem. A well-known collector once said that his love for Yixing started with the appreciation of Yixing clays grew with the exploration of Yixing clays and was ultimately fulfilled with an understanding of Yixing clays.

There has always been an intimacy between Yixing teapots and collectors that few other forms of ceramic art can even approach. Its function as a teaware invites the collector to visit his or her favorite pieces regularly, handling and using them to enhance the tea he or she also loves. Since the time of Gong Chun, collectors have not only paid top-dollar in the pursuit of high-quality Yixing teapots, many have, in fact, participated in the design and creation of Yixing teaware. This fashion reached its peak in the middle of the Qing Dynasty, and the most significant and influential Yixing lover at that time was Chen Meng Shen (1768 - 1822). Chen was not a potter. He was a local government officer, famous for his works of calligraphy and seal carving. He had befriended several famous Yixing potters, not the least of whom were Yang Pong Nian and Shao Er Chun. Chen designed and drew many different styles of teapots, letting Yang and Shao use his drawings to make new kinds of teapots. Chen himself would then often engrave calligraphy on them. Their joint efforts promoted the art of Yixing teaware to a higher shelf. Their designs have been reproduced countless times throughout all the years since, and their majestic achievements have been the study of generations of Yixing potters and collectors.

Chinese ceramics, calligraphy, seal carving and painting are all very sophisticated art forms. Yixing teaware provides a medium that condenses all these arts into pieces that capture aspects of all of them - focused so inspiringly into beautiful and functional pieces. Tea itself, its production and appreciation, could also be on that list of sophisticated Chinese arts, and it's therefore no surprise that Yixing teaware has enjoyed such intimacy and status in Chinese tea culture. This age-old marriage between tea art and teaware reciprocally encourages the refinement and elevation of both.

China's political and economic centers started to diverge after the Ming Dynasty, during the Qing Dynasty (1644 - 1911): The northern cities remained the home of the emperor, royal family and central government, while the economic powerhouse gradually moved to southern cities along the Yangtze River and the coast. This separation gradually forced the styles of Yixing teaware to evolve and expand, suiting the different tea drinking habits of the northern and southern cities. Tea lovers from the northern cities tended to be government officials, and they liked green teas or flowered teas better. They often shared tea with more people and liked to show off the craftsmanship of their teapots. Therefore, the teapots crafted for that market were of bigger sizes and were often engraved by famous calligraphers or painted by

renowned artists of the day. On the other hand, tea lovers in the southern cities were either commoners or affluent businessmen. They appreciated finely crafted and roasted teas, such as oolongs from Wuyi and Anxi, and had developed the tradition of "gongfu" brewing, primarily using smaller teapots. Yixing potters, with their talent and variety of superb clays, quickly adapted to these market changes and produced a vast array of teapots - from the most stately and luxurious looking to the miniature and delicate. Again, one can see how the changes in Chinese tea culture and the evolution of Yixing teaware have mutually enriched one other.

Looking back from a modern perspective, it is interesting to wonder about the fact that when the Ming Dynasty emperor abolished the making of powdered teas, he didn't he realize he had actually been the spark that triggered a volcanic revolution in Chinese tea culture. A vast array of teaware and whole-leaf tea would follow that one small event. The creation of Yixing teaware may just have been a matter of course, meeting a demand for vessels to steep the new teas in, but they have since become so much more. They are in many ways the pinnacle of teaware, both in terms of aesthetics and utility. The extraordinary artistic and functional accomplishments of Yixing teaware can only be explained if we consider these three factors together: the unique and precious Yixing ores/ clays, the highly talented and skilled artisans and the passion of tea lovers, which supports the transmission of this tradition, generation after generation to the present day.

They say the great Emperor Qianlong treasured tea enough that he brewed it in secret with his own august hands, though the son of the gods was forbidden such mundane activities. He also loved to leave the Forbidden City in secret, basking in the glory of ordinariness. He enjoyed the mystery and danger of being amongst his people. He would often disguise himself to walk the streets, visit teahouses and watch shows, admiring the everyday lives of his subjects. One evening, he was strolling home from a show, his bodyguards walking several paces behind to remain anonymous. The emperor suddenly stopped dead in his tracks, uplifted to Heaven by the deep and lasting fragrance of a very fine tea, as fine as the tribute teas shared only with the palace. It smelled of nutty, fruity plums and the best of Chinese herbs, filling the whole of his mind with nostalgia. "What wonderful tea!" he thought. And yet, the only dwelling nearby belonged to a simple farmer. The emperor was curious beyond containment, walking to the open door and with courtesy exclaiming, "Excuse me?" into the dark, lamplit interior, which was so simply adorned with a small shrine to the local land god, a table and two chairs, one of which was occupied by a very old man, whose wrinkles were as telling as the crags of distant Yellow Mountain. "Hello, old friend," the emperor began. "Might I come in?"

"Sure. 'Tis a fine night for a guest," the old man replied with a sweet smile. "Have a seat and share some tea, if you will."

The emperor went inside, signaling to his guards to wait for him, full of joy that he lived in a world so civilized and prosperous that even a simple farmer understood the Way of Tea. The two drank cup after cup of one of the darkest, most delectable aged teas the emperor had ever tasted. Each cup transported him further and further into the mountains, like discovering a partially hidden path leading up - the kind so seldom used that it is covered with brush, and only discernible to the true mountain man. He lost himself in its splendor, and lost touch with time as well. After some indeterminate number of cups, he looked into the old man's eyes and realized that there was a great and deep wisdom twinkling through the years of life they had observed, many more passing seasons than he. "What is this magical tea?" wondered the emperor. To which the old man giggled in an embarrassed way, "Oh no, noble sir, though I usually do trade for some leaves as I can each year, this year the drought made that impossible. Fortunately, the gods and the wisdom of my ancestors left me this amazing teapot from Jiangsu, used by my father and his father before him, back more than a hundred years. It has seen so much tea, friend, that it brews such liquor with a bit of boiled spring water poured through it."

The emperor was awestruck. He spent half an hour admiring the old pot, holding it up to the light with precious grace and gentle strokes befitting imperial jade. The old man answered all his questions, telling him all he knew of the pot and its origins. A man of tea is changed by such encounters, and the emperor was as pure a Chajin as any. He knew that he had made a lifelong friend tonight, both in the old man and his pot.

Very soon after, the emperor arranged for the old man to come into some fortunate circumstances that increased his family's holdings greatly, without revealing that the newfound abundance was a gift from anyone, let alone the throne. As far as the old man knew, his family was blessed. He also sent envoys to Yixing to bring back the best pots they could find, like the old man's. The craftsmen there were also to be honored. Over the years, the emperor and the old man shared many more wonderful tea sessions together, and more than a few exciting adventures as well, though those are other tea tales for other times...