|

|

When I repeat what my teacher, Master Lin Pin Xiang, always says about teaware, "There is zisha and there is no second!" I feel how strong of a statement this is reflected in the widening, startled eyes of the listener who glares back a "Really?" Usually, Daoist and Buddhist masters don't like absolutes. Lao Tze said, "He who knows doesn't speak, while he who speaks doesn't know." The Buddha himself avoided hardline tactics, as words and concepts never hold enough weight to be absolute, though they may point the direction towards absolute. Worse, taking a strong stance invites argument and disagreement. It is drawing a line intellectual types will cross just to play devil's advocate. Whenever people came to the Buddha with argumentative questions, or questions that sought to explore definitively absolute principles, he would stay silent - avoiding controversy, and, ultimately, answering with his silence and strong presence in the moment. And yet, despite the fact that our hearts are more loose, carefree and easy-going (Master Lin's more relaxed and centered than mine), we still pronounce that zisha teaware is the undisputed heavyweight champion of the world. Actually, this isn't meant to stir controversy. We make the claim because there is truth in it. More importantly, this claim is an invitation to explore and experiment, and rather than being put off by the idea that there "is no second" after Yixing zisha clay, take it as a challenge - an opportunity to explore, learn and discover genuine Yixing clay and test it out with your favorite teas. So, once again, I throw down the gauntlet. You ask what teaware is good for tea, to which I grin in a sly way and exclaim, "There is zisha and there is no second!"

I sincerely hope that this issue inspires you to dive in and begin to explore the wonderful world of zisha, learning to appreciate the craftsmanship and aesthetic beauty that is so deeply enriched by centuries of mastery. I hope you also begin to love the simple curves and elegance of earthen colors. And as you work with zisha clay, and begin gongfu brewing, I also hope you discover the magical and wondrous effect that zisha has on tea, which is the real reason Yixing is the "Father of Tea." There is a great magic in Yixing teaware, and the further you travel on a tea road, the more you fall in love with Yixingware. Sometimes, I must confess, I choose tea I will drink that day not based on the season, occasion and other factors that usually inform such decisions, but based exclusively on which of the Center's teapots I wish to caress and love that day! The pots here have become dear friends, and I honestly do occasionally come to miss them.

In this article, I hope to address the three main topics of inquiry that always come up when one begins exploring Yixingware. (They certainly did for me.) I'm sure that many of you will also be wondering about these issues: First, how do we choose an Yixing pot? We will explore clay types and why they are important, as well as the shape and design of the pot and its influence on tea preparation. The second question most beginners have is about using which kind of pot for which teas. We will discuss how to use just one pot, and how many and which kind of Yixing pot you would need to brew any and all teas gongfu style. Finally, our Yixing journey will take us back in time, as we explore antique Yixingware and why it makes much better tea than modern pots. Now is a great time to put a kettle on, get out your favorite pot and steep up some nice Yixing gongfu red tea, and we'll start our journey with how to choose an Yixing pot while yours steeps!

Wherever a discussion of gongfu tea or Yixing comes up, tea lovers are always asking about how to choose an Yixing pot. Journeys into a subject are always from the gross to the subtle, the general to the specific. To begin moving towards choosing a teapot, from as wide and open a vantage as possible, I would like to start by saying that there is certainly a story and some destiny involved in finding your pot. To adapt the saying in our tradition about how "as the person seeks the Leaf, the Leaf seeks the person," we could also say that as the person seeks the teapot, the teapot seeks the person. The best pots are found through travel, friendship and generosity, meeting the craftsman him or herself or a story that enriches the pot, imbuing it with a charm and glow beyond its form.

As a Chajin learns to re-connect to Nature, feeling more and more within the world, she restores and regains the indigenous, wild soul - watering the dusty, soulless worldview she was raised in and allowing green life to grow again. The living world starts to come alive again; the inanimate world she was socialized to see returns to the breathing, living world of her childhood. If you let Tea into your heart, she helps you to see the Nature in things: to look at food and see the sun, rain and soil, as well as the farmer's work; to look at a glass and see the sand, the beach and the endless ocean waves that made it over centuries; and, of course, to look deeper into one's teaware and see a living friend made of ore formed over millions of years, mined and ground, shaped and sculpted into this pot. When you stand back, you realize that it actually took millions of years to make your teapot, and that it was made as much by Mother Earth as by the craftsman.

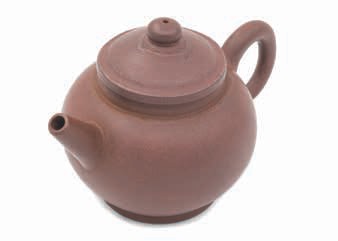

Moving from the more universal, natural aspects of teaware to the material itself, one must start the evaluative process with some aesthetics. Teapot aesthetics, however, are subjective and difficult to discuss. My favorite style of pot, for example, is Ju Lun Zhu (巨 輪珠), which, as we discussed in the March issue of this year, are very simple and rustic - intentionally so. They are often unfinished on the inside, have loose lids and craft marks, which are intentionally left in place so that the pots feel unfinished. Other pots are fancy, with elegance and grace in curvy flow that is delightful. A personal balance must be struck between form and function, beauty and usefulness.

From a very general perspective, the same aesthetic governs all of tea practice, from farming to tea processing, and chaxi to brewing: harmony. It is balance and harmony that makes a great pot. This includes the space around the button/pearl, through the handle and even around the spout. Echoing the favorite analogy of our eldest teacher, Lao Tze, the usefulness of the teapot also lies in its space - the tea flows through it, just as the Dao flows through us when we are clean and pure. And then, when we brew our teas, the improvement in aroma and flavor will help us judge our friendship with any given pot. Because of this combination of function and design, Yixing teapots have achieved a legacy of their own, finding a central place in the story of tea.

If the spout is dainty and soft, the handle will be smaller, whereas a pot with a strong, forceful spout will need a jutted, equally strong handle to create balance. Master Lin often refers to the aesthetics of a teapot as a horse: the spout is the horse's head and the handle its reigns, so if the horse is bucking wildly, chomping to gallop away, the reigns must be pulled back and away more forcibly. If the horse is trotting gently, on the other hand, the reigns can be let go of, given over to the horse. Holding a pot up, there should be balance and harmony between the spout and handle. This is actually more than aesthetics, as it will also influence the way the pot pours. The button/ pearl also needs to be the right size and shape to harmonize with the spout and handle properly, anchoring the symmetry, since it is centered right above the body. And, of course, the body itself will define the spout and handle, so it is made first. If you look at some of the classic designs in this magazine, you will see that the great masters who created these designs were brilliant at creating a moving harmony and grace.

Yixing pots are not made on wheels, but slab-built. They are tapped, pounded, shaped and sculpted by hand. This process can take days or even weeks to complete. There is a tremendous art and skill that goes into this process, and those who devote themselves to this craft are truly artists of the highest order. That said, I personally am far more interested in Yixingware as a teapot, as function, than as art. This doesn't mean that it is somehow lesser when it is pure art, or even that I am unable to appreciate the art of a beautiful pot; it means that for me the beauty of an Yixing pot is in the place where its form and function meet - when the harmony and balance of the pot results not just in something beautiful to the eyes, but something that is also a glory to touch, hold and use. And, most importantly, the greatest beauty for me comes when a pot makes fine tea.

The art and craftsmanship in Yixing has continued until the modern era, with amazingly beautiful and even new, ingenious designs being created all the time. And those who collect Yixingware as art are more than fully welcome to do so - I celebrate this art, in fact. Art doesn't have to be functional, even teapot art. A painting or sculpture doesn't have to do something other than inspire us. However, I do find it sad that since the road to success has been so strongly defined in artistic terms, Yixing craftsmanship has very much lost the relationship between Yixing pots and tea. Fine pots are judged by appearance nowadays. The relationship between the pot and gongfu tea, and worse, the clay and tea (which we will get to shortly), has, for the most part, been lost. It is harder nowadays to find a simple teapot, in other words. Though I don't collect Yixingware as art, I love it and appreciate it - I just wish Yixing craftsmanship struck a greater balance between teapot art and function, as it did back in the olden days when there were three kinds of pots: those made simple and exclusively for tea brewing without consideration for aesthetics, the pots made by masters that had an exquisite balance of form and function and, finally, the pots that were purely artistic and made to be admired rather than used.

While I appreciate the art of Yixing, function is more relevant to me as a Chajin, so I would like to discuss some of the aesthetic factors that also have a functional dimension, as they are the focus of my own decisions when choosing an Yixing pot.

Firstly, plain teapots make the best tea. Any carving or dimensional decoration will influence the way the pot holds temperature and result in lower quality tea. A simple design is always better for tea. Carvings or decorations that stick out from the pot create more surface area and you lose some of the capillary action that makes Yixing pots breathe. This means that the tea won't be as stable and the temperature less consistent. Remember, consistency is the key to fine brewing in gongfu style. If the temperature stays the same and my movements are gentle and soft, the tea becomes more patient, smooth and balanced. Tea trees thrive in environments that have gentle, smooth and consistent temperature and humidity, so we prepare tea in the same way as it grows in Nature.

Personally, I agree with Lu Yu, who said in the Tea Sutra (茶經), "The spirit of tea is frugality." I think that he was paying homage to the simplicity of Chajin and of tea. Tea is very much a ceremony to celebrate the ordinary. For me, the best pots are simple. I like humble, rustic teapots like Ju Lun Zhu (巨輪珠) for this reason. I think the beauty and glory of Yixingware is expressed beautifully in the simple and ordinary pot, which makes nice tea and brings a glow to the simple and ordinary moments of our lives, which translates to more gratitude and appreciation of life in general.

A well-made teapot should feel like it is part of your hand. It should attach to you when you pick it up, as though it was made to be used. The best pots really do feel like they were made for your hand, and rise up so gently and perfectly. There is a connection that is tacit, like a magnetic attraction, when you hold the pot by the body with your off-hand and slowly bring it towards your strong hand. They snap together perfectly. This may sound too metaphysical, but there is an actual sensation of connection when you bring a fine pot to and from the strong hand in this way! The best teapots are also perfectly balanced, which results in a very smooth and gentle pour. The center of balance is harmonized between the spout and the handle, allowing for a graceful decantation of the tea liquor. There is more in the craftsmanship that lends itself to fine tea, but to separate the qualities of the pot from the aesthetic aspects, I have called these criteria "design."

The design of a pot refers to the shape, the spout design and pour, as well as other details of the construction that are less tangled up with aesthetics and more pure function. In other words, some of the features of a pot are best when crafted in an aesthetically pleasing and equally functional way. What we will discuss now as the "design" of the pot are aspects of the pot that are more strictly functional, and so only really become evident when using the pot to prepare tea.

The first aspect of design worth mentioning was already discussed above, as it is also an aspect of the aesthetics of a pot: a good pot should be balanced well. When a pot is balanced well, it will pour smoothly and more gracefully, resulting in finer tea. The second aspect of a well-designed pot is often contrary to the craftsmanship and artistic sensibility of teapot makers and collectors both. It is often assumed that well-crafted pots should have a perfect, tight-fitting lid. Teapot makers strive to achieve this, and collectors often check when they are evaluating a pot. However, I always wondered why less antique pots had such tight lids, especially considering that modern craftsmen and collectors both often say that the talent and skill of their ancestors far exceeded the modern era. Over time, I began to realize that a tight lid affects the pour. Oftentimes, the small amount of air entering through the hole in the button/pearl or lid is not enough. I even noticed some tea teachers leaning the lid open at later stages in the pour, especially with teas like sheng puerh, when you want to decant the liquor as quickly as possible. Since modern pots are often created with an ideal of a tight lid, these tea brewers had naturally found that tilting the lid at the end of the pour increased flow. I naturally started experimenting, and have since incorporated this technique with some of our pots. But it is not always needed with our antique pots, as the give in the lid allows more airflow, and therefore, greater control over the pour. One could argue that the looseness of antique lids has to do with wood-firing and less control over temperature and shrinkage, which may be true in some cases, but I feel it also has to do with this issue.

Another important design feature is a roundish body that opens in the middle, leaving room for the tea leaves to open and expand. This helps promote smooth and clear tea sessions from start to finish. The more round a pot is, fattening at the middle like an oval, the more suitable it will be for every kind of tea, from puerh to striped oolong teas. Other shapes may be better for certain kinds of tea only, which we will talk about later on.

Of course, the spout is also important in tea brewing. While it is nice to have a built-in filter, we have found that a single hole makes for a smoother pour and brighter tea. The filter separates the tea, breaking its structure. Also, you can learn and then practice how to add the leaves in a way that the bits will stay in the pot (the bits are important as they add consistency, especially in the early steepings when the larger leaves haven't yet opened). You simply sandwich the bits between the larger leaves. The spout shape is also important, as it will affect the range of distance the pot pours as well as the speed of the flow. Our favorite spouts are the cannon spouts of Ju Lun Zhu, as they afford the greatest control over the distance and flow of tea liquor. Other spouts have a much more limited distance and speed.

These are some of the design features we look for in a good pot. Add some water to a pot you are considering and feel the balance, observe the pour - its distance and speed. Taste the water from it as well. It should be smooth, and better than the water not in the pot in all the ways we have so often discussed in the Ten Qualities of a Fine Tea. Much of the smooth, soft roundness of the water or tea liquor has to do with the clay, though.

The clay plays a huge role in the quality of a pot, perhaps more than any other factor. Many times when choosing an antique pot, we have to excuse design flaws, and often forgive aesthetic issues (maybe even chips or cracks), but we do so because the clay of these pots is so much better. This demonstrates how important the clay of a pot is. It is the clay more than anything else that affects the structure and quality of tea liquor.

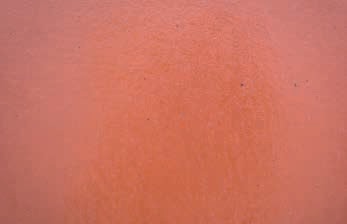

There are three large families of Yixing clay: zisha (紫泥, purple-sand), hongni (紅泥, red clays) and duanni (段泥, yellow, gray and green clays). It is zisha clay that was married to tea all those centuries ago, and zisha clay that makes Yixing the "Teapot City" (sometimes also referred to as the "Zisha City"). Sometimes, Chinese people even refer to all Yixingware as "Zisha." Much more than the two other families, zisha makes smooth, bright tea. A nice duanni pot can be good to have for green, white or yellow teas. Hongni pots are often nice for lightly-oxidized oolong, due to the high iron content. However, for most teas, in most situations, it is zisha that makes the best tea.

Originally, only zisha was used to make teapots. In the Ming Dynasty (1368 - 1644), all teapots were very large and hongni cannot be used to make such large pots, as the shape would warp in the kiln. Therefore, only zisha was mined for teapots. Zisha is a much richer clay, and hongni/ duanni are both missing or deficient in several of the minerals and compounds found in zisha ore.

Clay is the most difficult aspect of teapot purchasing and evaluation these days, though. In the late 1990s, the mines of Yixing were all closed. Most of the ore used to produce Yixing clay comes from the Yellow Dragon or Blue-Green Dragon mountains. All of these mines were closed, and they remain walled in, and locked with a giant wooden door, even to this day. As a result, genuine Yixing ore and the clay that is processed from it have become scarcer and more expensive. When you put this together with the issue of craftspeople in Yixing maintaining the art of teapot creation while losing the relationship pots have to tea, you have a problem for the tea lover. You see, as potters have focused more and more on form, and less and less on tea brewing, they have begun to seek alternative ore and clay from other regions of Jiangsu and even Anhui to create their pots. To them, Yixingware is much more about the technique than it is about the ore. What makes a teapot Yixingware, they think, is the method used to make it, as well as the style and shape. As long as the pots are similar in color to traditional Yixing ore, they don't mind where it is from. And much of the coloration can be achieved these days by adding iron oxide, for example. This is a serious issue for the Chajin who is seeking a pot to make fine tea, which is as much or more about the clay composition as it is about the design and craftsmanship.

Almost all of what is sold in the market as "Yixingware" contains no actual Yixing ore. We don't have a statistic, but experts in Yixing have suggested that it is higher than ninety percent. If, as we suggest, and as you should experiment, much of what has made Yixingware famous these five centuries, marrying it to Tea, is the effect this clay has on tea liquor - if that is true, then using alternative ores/clays to produce pots in Yixingware shapes will result in teaware that doesn't have the desired effect, which is happening. Very often, we meet tea lovers who ask us if Yixing is all hype. They start out with a porcelain pot, or perhaps another ceramicist's work, and then get an "Yixing" teapot online or on a trip to China. After returning home, they try the new pot out and find it really is not that different from their other pot. (Some even tell us it is worse!) And this may be true: maybe clays from random places in Jiangsu or Anhui, often blended with powders from all over, aren't as good for tea as porcelain, purion or other kinds of ceramics. But genuine Zisha is! It has been for five hundred years.

We hope this highlights how important it is to get a genuine zisha pot, made from real ore, mined before the mines were closed. It is this that will change your tea. When it comes to clay, aside from the importance of provenance and choosing zisha (for most teas), the longer the ore ferments, the better, and the older the clay is, the better it is for tea. Some potters have asked us why this is the case and we genuinely do not know. It may seem to make no sense, as the organics in clay are all wiped out in the firing. These skeptics suggest that the greater the fermentation of the ore or clay, the easier it is for the potters to work with, since Yixingware is hand-built, and this is definitely true. More than one potter in Yixing has told us that the older the ore and/or clay, the smoother and more refined it is. This means it will respond to their hands better, resulting in subtle refinement. The mystery we cannot explain is why these pots make better tea clay-wise? We have done experiments with various ages of clay and their effects on tea liquor and found age to be a very prominent factor. In fact, there was some Qing Dynasty (1644 - 1911) clay offered at auction in the late 1980s. The batch was purchased by a Malaysian teapot collector and several pots were commissioned from it. And these pots make amazing tea, commanding very high prices amongst tea lovers. The clay was forgotten and found more than a hundred years later. While it is genuinely assumed that the abundance of ore and clay meant that potters of yesteryear fermented theirs much longer than modern times, it is unlikely they did so for that long. And yet, it did affect the tea. It seems clear to us that past masters fermented their clay longer not just because of an abundance, but because doing so made for better clay to work with and also had a pleasant influence on the tea prepared in such pots, which was a far more relevant factor in a pot's overall quality than it is today.

We have also found that the best Zisha clays nowadays are unblended, which is called "Qing Shui Ni (清水 泥)." Using just one ore, from one vein, fermented to produce a single clay results in better tea. There are many kinds of ore in each family (zisha, hongni and duanni). Long ago, masters were much better at blending ore, not just for aesthetics, but for the effect on tea liquor. Sadly, such secrets are lost now, making pure clay the best option (all things equal).

I have been studying Yixing for many years and am still very much a beginner. It is a deep and vast art, with centuries of history, traditions passed on from master to disciple, and incorporates geology, mining, clay production, teapot making, firing, decoration and appreciation of pots - much more than anyone could learn in a lifetime. There is, therefore, a lot more to choosing a pot than our introduction has covered, but I want to move on to one of the most asked questions, about which pot one should use for which tea and why.

When discussing which pot to use for each kind of tea, we should first discuss a slightly misleading idea that many people who are new to gongfu tea have, which is that you must have one teapot for each kind of tea. Yixingware is unglazed, and has a double-pore structure, which means the pores of the pot absorb the oils of a tea and "season" over time, becoming shinier, more beautiful and filled with tea spirit. It also means that after a long time, and many tea sessions, the pot will be able to transform plain water into smooth, bright and flavorful life - much like drinking tea, without the flavors and aromas. This process is wonderful and joyous; it is one of the great joys of a tea lover, in fact. And this means that you will need one pot for each of the kinds of tea you drink. But it is not necessary. Also, they say that when you put the right tea in the right pot and shower the outside the teapot will glow.

If you have only one pot, it is not necessary to designate it for just one tea. You can use your only pot for all teas. In order to do so, you should follow two guidelines: First, you should be strict about never leaving tea leaves in the pot for any amount of time at all. Clean the pot out immediately after a session. (If you have one pot for each kind of tea, you can leave the tea leaves in the pot and return for a second session later. This helps season the pot, in fact). Secondly, you will not be able to season the pot, but should scour it every six months or so (depending on how much tea you drink). You can follow the scouring guidelines in this issue. Then, as you accumulate pots, you can start to segregate them according to type of tea. After you get a second one, for example, you could have one for light teas (like lightlyoxidized oolong or young sheng puerh) and one for dark teas (like traditionallyprocessed oolong or shou puerh).

In our tradition, we practice not being hoarders, collecting too many pots that one will never use. Many of the pots that are just sitting on your shelf collecting dust could be a treasure to a beginning tea lover - one they will honor by caring for it with deep respect and using it every day. A fine teapot is meant to be used. Just as tea trees (even wild ones) do not thrive as well when people don't visit them, offer prayers and prune their leaves, in the same way, a pot won't glow without the love of a friend and beautiful tea flowing through it. For this reason, we practice only using a maximum of fifteen pots, as shown in the chart. Most people will really only need around ten, as the extra five are more for those serving lots of tea in many different situations.

If you stick to the "fifteen pot" principle, you will not only stop yourself from unnecessary spending or from collecting pots you yourself will never use, you will also improve your collection over time, because every time you go teapot shopping, you will have to ask yourself, "Which of my fifteen pots will this one replace?" Then, if it doesn't perform one of the fifteen roles better than the pot you already have, you will leave it in the store for another Chajin. If it does perform better in some way, then you can bring it home, and either give the old one away to a friend or sell it to help pay for the new one. In this way, your entire collection will slowly improve, developing into a better and more refined Yixing tea gathering!

What were the untold riches he spoke of? Does the old rascal watch us now? Perhaps escaping time Offered the old codger A glimpse of all the cups shared, Friendships toasted, And loves vowed true. Maybe he watches us now, From just past the fuzzy rim Of an upturned pot, Grinning ear to ear With the satisfaction Of the last few drops.

Earth-polished gems Bestowed upon the Queen of Trees In an offering of love beyond time A Tribute paid in Clay and Leaf from the same source Heaven, Earth and the Heart

The spirit sought a home, A body to hold the sacred waters: An earthen home, Made of the same elements From which She grew, To Shine in Her glory. Just as She called to the shamans, Long before there was a pot, Offering to guide the human soul home, So did She appear before these, In the guise of an old immortal, Offering untold riches in the hills, Creating the way for the Earthen sand to become A teapot-shaped altar, Beginning an unending stream of joy That leads over the horizon And back to this very cup.

The shape does play a role in which pot is useful for which kind of tea. This is, however, a very deep topic that extends beyond the scope of this introductory article. There are a lot of nuances when it comes to shape, and we feel that the clay type and purity have a much greater bearing on tea liquor than the shape (which is not to say that shape is not important). As we mentioned above, a round body that opens up a bit in the middle is always the ideal shape for all kinds of tea, so if you are looking for a general pot to use with all teas, or aren't sure about what shape to use, always look for a nice round body that expands slightly in the middle, as it will produce the best tea.

In general, young sheng puerh is very nice in pots that are wide with a flat lid. It is nice to use a bigger pot for all compressed teas, leaving extra room for the leaves to open more. The spout should also not be restricted, as puerh needs to be decanted quickly - moments more can make the tea too bitter and/or astringent.

Ball-shaped oolongs do best in a perfectly round pot. They also need lots of room to open up, and need to be nursed for the first few steepings so that they don't roll over the spout side and open unevenly. We want all the balls to open simultaneously in a symphony of fragrance and Qi. Gentle and round pots can help facilitate this.

Striped oolongs, like Wuyi Cliff Tea, are best in flat, wide pots with huge openings. These leaves are large and brittle, so a large opening makes it easy to get them in the pot without breaking them. The wide, flat shape means the leaves can open uniformly and will not move too much.

Red teas do best in thick-walled, tall pots. Red tea is often best brewed for long periods, and these tall, thick pots conserve heat and allow the leaves to float, opening uniformly and providing a smooth liquor that is bright and sweet.

When brewing light teas gongfu, like white, green or yellow, we like a small duanni pot that is flatter. These teas are more about fragrance, and are often served at lower temperature, so the heat preservation and smoothness of good zisha is less important. A delicate, thin hongni pot from good clay can be used to brew very nice lightlyoxidized oolong as well. For this, a round pot would, of course, be ideal for ball-shaped examples, and a wide, flat pot with a large opening would be good for Baozhong.

Our favorite shape is Ju Lun Zhu, as we have often repeated. It is perfect for all kinds of tea, with a round body, thick walls and a cannon spout for maximum control of pouring speed and distance. These pots work well with every kind of tea, and we love the simple, humble and rustic aesthetic of them as well.

If you read the "Styles of Yixing Teapots" article beginning on page 61, we offer some more guidance for shape and tea. We love using a Si Ting pot, for example, for delicate Taiwanese oolong, especially when it is lightly oxidized; or a Meng Chen Pear pot for Wuyi Cliff Tea, since it is flat, with a large mouth.

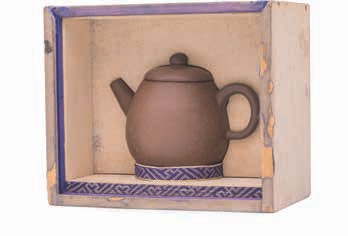

In the June issue of this year, I discussed several reasons why we love antique teaware. Back when I first started drinking tea, we didn't know any modern teapot makers who loved drinking tea and were interested in the relationship between clay and tea liquor. This meant we had to buy antique pots, which are more expensive, you cannot choose the shape and style and there is always the danger of buying a fake one. It takes time to learn which pot is authentic and which isn't - you have to touch lots of pots. I was fortunate to have a great teacher to show me how to identify authentic pots and who even gave me my first Qing Dynasty pot to use as a comparison when shopping (I often took it out with me, just in case). Nowadays, we are lucky to have Masters Zhou and Chen in our lives, making pots in any shape we want for affordable prices, and, most importantly, using good, authentic clay that makes great tea. (And for teaching us!)

Still, there is a magic in antique pots. The producers of them devoted their whole lives to the creation of Yixingware, living much simpler and more concentrated lives without all of the distractions of modern living. I wrote about how the craft has not been lost, but the relationship to tea has. In the June article, I also mentioned how the clean living and lifelong devotion of past masters improved their work. A couple of you asked me if maybe the quality of pots back then was as varied as now and then only the good ones survived to the present. Are the antique pots we seek the best of their time? Actually, this is not true. The best pots, made by masters, are very expensive, as they are desired by Yixing collectors. Chajin like myself much prefer the everyday, ordinary wares from that time - the simple, rustic pots that have been used ever since. We like the wares that the potters took home because they were too flawed to sell or the pots that ordinary people used day in and day out, not the nice pots commissioned for wealthy people, or at least collected by wealthy businessmen today. Simple antique pots, often with slight chips in the lid, that were made for ordinary people to use every day are cheaper than other antiques and make better tea. There is also the magic of owning a pot that has been held by many Chajin - generations of adoration and leaves and water meeting over and again in these gorgeous friends. A pot that has been loved and used, cared for enough to survive the journey through time, glows with a magic all its own. You feel honored to be a part of this sacred lineage of stewards of the pot!

Teaware is the earth element in the alchemy of tea. When it is fired, though, it turns completely to fire - all the atoms moving and rolling around in the extreme heat of the kiln. Therefore, the older the pot is, the further it gets from its firing, the more it returns to earth element, settling back down into the configuration of metals and minerals it held when it was in the ground. Since Yixingware is handbuilt, instead of thrown on a wheel, one could say that the overall structure of the pot is closer to the original make-up of the ore than clay which is spun around a wheel.

The final reason why antique pots are so much better is due to the most important factor of a pot, as we have discussed repeatedly: the clay. As Yixing craftsmanship has drifted further and further into art, and away from the original ore/clay and its relationship to tea, many arts have been lost. Since the mines closed and most potters have switched to using clay from other regions, the ore-selecting and mining skills have died. Also, the fermentation of the ore and clay-processing secrets that had been cultivated by families for hundreds of years have also been lost. Master Zhou is trying to experiment with ore fermentation and clay processing to create better clay for tea, but he is doing so alone and without guidance. (It took around five years of trial and error to get to a level of clay that Henry and Master Lin approved of.) The techniques of refining the clay are mostly lost, especially the inner secrets held by lineages, which weren't written down or shared publicly. Finally, the same thing is true of the wood-firing masters who controlled the dragon kilns for centuries. As craftspeople have switched to gas or electric firing, these powerful and elemental kilns have become a tourist destination. They are being fired more and more as wood-firing once again becomes popular, and we hope these techniques will also be further refined in the future.

For all these reasons and more, antique pots are almost always better than modern ones. There are exceptions in both directions, however. If you are interested in finding an antique Yixing pot, we would recommend treading with great care, as there are a lot of fake pots and you may wind up paying some "tuition" without the guidance of a knowledgeable collector or teacher. But when you do find an authentic pot, you will be rewarded for your efforts!