|

|

Purple-Sand clay teapots have a history of more than five hundred years. In Chinese, they are known as Zisha Hu (紫砂壺), with the characters Zisha (紫砂) literally meaning "purple sand." Throughout this history, there have been several main waves in popularity of collecting Zisha clay pots, including the late Ming Dynasty, the reign of the Qianlong Emperor during the Qing Dynasty, the late Qing and early Republic, and the present day. The last thirty-odd years from the 1980s until now have seen a particular swell of interest in these pots, which is still going strong. The main reason for these waves, of course, was the circumstances during these periods of history; these were the "golden ages," when China was flourishing in terms of both culture and economy, resulting in the so-called "fine collections from times of peace and prosperity."

The past few decades have seen large volumes of archaeological research surface. The current body of research has come a long way since 1937, when Zhang Hong (張虹) and Li Jingkang (李景康) wrote their Illustrated Study of Yangxian Sand Teapots (陽羨 砂壺圖考), when the existing research was scarce and inaccessible (Yangxian is an old name for Yixing). Even compared to 1982, when Zhan Xunhua (詹勛華) compiled the Graphic Archive of Yixing Pottery (宜興陶器圖 譜), the material available today is much more plentiful. The abundance of information that we now benefit from is the result of ever-developing science and technology, ease of information sharing, and of course, decades of hard work by archaeologists and historians. We who are fascinated by Purple-Sand clay must be sure to honor all this research. Below is a selection of some of the more eminent research about Zisha clay pottery, collated and organized to provide a reference to the existing body of research, so that the various materials may support each other and be useful for future studies.

For a long time, the main source for archaeological research regarding Yixing Purple-Sand clay was a work published in 1984: A Report on Findings from Ancient Kiln Sites at Yangjiao Mountain, Yixing (宜興羊角山 古窑址調查簡報), in the Collected Reports on Excavations from China's Ancient Kilns (中國古代窑址調查 發掘報告集). Some years earlier in 1976, while workers from the Yixing Hongqi Pottery Factory were removing some clay from the mountainside, they discovered an ancient kiln site on Lishu Village's Yangjiao ("Sheep's Horn") Mountain. This discovery was very significant for shedding light on the origins of Yixing Purple-Sand clay pottery. According to the records, this ancient kiln was a small example of the type known as a Dragon Kiln, measuring around ten meters long and just over a meter wide. In a pile of scrapped pottery next to the kiln, they discovered a great number of rejected pieces of Purple-Sand clay pottery from the period. Most of the unearthed pieces were from various types of teapot, and included spouts, teapot bodies, handles and lids. The scholars at the time classified the pile of fragments by layers, and noticed that some of the teapot spouts were decorated by shaping them into dragons, which was consistent with the style of the Dragon and Tiger vases that were popular in the south during the Song Dynasty. They also discovered some small Song Dynasty bricks in the same spot. From this, they deduced that the earliest pieces were from the middle of the Northern Song Dynasty, with production flourishing during the Southern Song; the latest pieces were produced as recently as the early Ming Dynasty.

However, there have been differing viewpoints on this in scholarly circles over the years, with some questioning whether the pottery remnants from Yangjiao Mountain provide sufficient evidence to reach these conclusions. For example, historian Mr. Song Boyin (宋伯胤) from the Nanjing Museum writes: "One cannot rely on the similarity between such a small number of pottery shapes and some relics excavated from Northern Song tombs; or on the fact that certain shapes don't appear after the Southern Song; or that the bricks from the brick pile are relatively small, or that they resemble bricks from the Northern Song. It's simply not enough evidence." Following this reasoning, Mr. Song maintains that the only way to get real answers would be to conduct a comprehensive archaeological survey in the area surrounding Yangjiao Mountain, using the proper scientific techniques. Archaeological expert Li Guangning (李廣寧) from Anhui Province also states that "The ancient kiln site at Yangjiao Mountain has never undergone scientific archaeological excavation... it is unsuitable to be cited as archaeological evidence... it's very hard to confirm that the site dates to any earlier than the reign of the Ming Emperor Jiajing." Moreover, as Mr. Li also points out, "Throughout China, more than one thousand Song Dynasty tombs have been excavated, yet to date, none of these tombs have yielded a single Purple-Sand clay teapot!"

Despite this research, it seems that perhaps because the many dynasties' worth of relics hiding beneath China's soil are so plentiful and so ancient, China's archaeological experts haven't had much time for a newcomer such as Purple-Sand clay, with its mere few hundred years of history. It wasn't until 2005, nearly thirty years after the Yangjiao Mountain dig, that interest began to pick up. Late that year, with the support of the Taipei Chengyang Foundation, archaeological experts from the Nanjing Museum, the Wuyi City Museum and the local museology department in Yixing joined forces to excavate an area of around 700 square meters, located at two historical sites on the southwest slopes of Shu Mountain (Shu Shan), near Dingshu Village (丁蜀鎮) in Yixing. After two years of work, the archaeologists discovered ten areas with remnants of kilns from different periods. Altogether, they unearthed more than three thousand pottery fragments from various soil strata. The fragments dated from the late Ming Dynasty to the early Republic of China, and included Zisha clay, Junware and other types of everyday pottery. In September 2008, the Nanjing Museum held an exhibition showcasing fragments from the Yangjiao and Shushan digs, entitled Whispers of Purple Jade: A Collection of Purple-Sand Clay Artifacts.

The Whispers of Purple Jade exhibit also included artifacts excavated from an ancient well site at Jinsha Square in Jintan City, Jiangsu Province. The ceramic fragments excavated from this well dated to as early as the reign of the Ming Emperor Zhengde, and as late as the reign of the last Ming Emperor, Chongzhen. Also unearthed at the same site was a teapot with a hooped handle at the top and a number of pots with spouts for boiling water, all of which were similar in shape and crafting technique to the late Ming pottery found at the Shushan site. The hoop-handled teapot bore a particulary strong resemblance to a similar pot, the Hoop-handled Persimmon Stem-Patterned Pot, found on Majia Mountain in Nanjing, Jiangsu, and dating to the twelfth year of the reign of the Ming Emperor Jiajing (1533). The two pots are so similar in terms of shape, clay and crafting and firing techniques, as to provide evidence that they are from the same period.

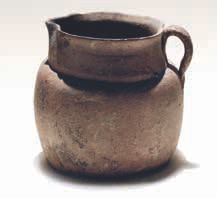

Of the Zisha implements that have been uncovered from the era of the Zhengde and Jiajing Emperors in the Ming Dynasty, a particulary fine example is the Drum-Shaped Four-handled Purple-Sand Clay Pot found in 1991 at Nanchan Temple in Wuxi, Jiangsu. This pot is heavy and thick-set (similar to the Gang style of bowl) with a purplish-brown color, and is made from a fairly coarse, gritty clay. The body of the pot is crafted in a similar fashion to that of the hoop-handled pot found in the Wujing tomb - it is formed from a top and bottom part, with a clearly visible join mark on the inside. It was fired without the use of a saggar (a protective clay case used when firing), so it displays quite a few blemishes caused by flames or debris. Experts speculate that it would have been used to boil water or tea. Along with this pot, the archaeologists also uncovered many pieces of blue-and-white porcelainware and jugs of the sort that were produced for everyday use. The Wujing tomb is a very important site for understanding the history and development of Chinese ceramics.

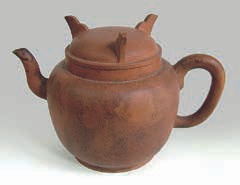

The earliest use for Zisha pots was likely for boiling water or tea. Gradually, they migrated away from the stove and began to be used for brewing tea instead, and so they became more refined. Most of the hoop-handled pots and jugs described above bear the signs of direct contact with flames, which also attests to these circumstances. In 2005 in Jiangsu Province, the site of a Ming Dynasty guard post was excavated on the south side of Datong Street in the city of Xuzhou. A type of Purple-Sand clay "pierced heart" teapot was found at this site, which was used for boiling water during the period from the reign of the Wanli Emperor to that of the Chongzhen Emperor. This type of pot resembles a sidehandle teapot in shape, but with the addition of a sort of hollow spout in the center, coming up from the base of the pot and protruding out the top, passing through the lid. This very scientific design increased the heatable surface area of the pot, thus allowing the water to boil faster. At the Shushan dig, a similar pot was also found in the late Ming to mid-Qing soil stratum. This pot had a similarly designed steam spout leading out from the side of the pot. From this, we can surmise that these Zisha "pierced heart" pots were a common household item in that period, though they are seldom seen nowadays.

You'll remember that earlier in this article we discussed the Hoop-handled Persimmon Stem-Patterned Pot found at Wujing's tomb from the Ming Jiajing period, in the city of Nanjing. Wujing (吳經) was a trusted eunuch of the Zhengde Emperor, whose temple name was Ming Wuzong (明武宗) and whose personal name was Zhu Haozhao (朱厚照). Although Wu Jing held as much power as a grand chancellor, he was also spoilt, arrogant and cruel. According to the Ming Dynasty Yanshan Tangbie Records (弇山堂別 集) by Wang Shizhen (王世貞), after the Jiajing Emperor succeeded to the throne, Wu Jing was sent before the local authorities and was sentenced to be banished to a military outpost in Xiaoling. Despite his fall from grace later in life, after his death the burial items found in his tomb were certainly nothing to be ashamed of. Numerous artifacts were uncovered in Wujing's tomb, including clay pots, porcelain plates, and more than 200 ceremonial weapons and pottery burial figurines. And, of course, there was the famous Hoop-handled Persimmon Stem-Patterned Pot.

They say that good things come in pairs - in 2002, a pair of Purple-Sand clay pots were unearthed that dated to the same era as the Wu Jing hoop-handled pot! Coincidentally, they were also found at the tomb of a eunuch. According to materials published by the Beijing Department of Cultural Relics and a report entitled The Ming Dynasty Eunuch Tombs at Beijing University of Industry and Commerce published by the Beijing Cultural Relic Research Institute, during construction work at the university, three tombs were discovered that turned out to belong to Ming Dynasty imperial eunuchs. According to the report, "A great many artifacts were discovered, including Purple-Sand clay teapots and teacups, and jade belts." One of the tombs belonged to a eunuch named Zhao Xizhang (趙西漳), who was buried in 1582, the tenth reigning year of the Wanli Emperor. An inscription found in the burial chamber tells that the owner of the tomb was an imperial eunuch by the name of Zhao Fen, with the style name Lan Gu and also called Xizhang. He was born in 1508, entered the palace at the age of seven, and served four emperors in his lifetime: the Wuzong, Shizong, Muzong and Shenzong Emperors.

The pair of Zisha pots, found in a niche in the wall on the west side of Zhao Xizhang's tomb are almost identical, with a straight mouth at the top, sloped shoulder, straight sides and a flat base with a small lip at the bottom. The lids are slightly rounded, with a knob on top. They have short, curved spouts, which are taller than the top of the pot, and tubular "ear-shaped" handles. These pots were made by fashioning the base, body, spout and handle separately, then joining them all together. The body of the pot is formed from a rectangular sheet of clay shaped into a round tube. One can observe small specks of mica throughout the pots, which suggests that the firing temperature may have been a little too low. Discovered along with the two pots were four Purple-Sand clay teacups of decreasing size, all a reddish-brown color and only 1.1 to 1.5 millimeters thick. Each teacup has a character imprinted into it using a square stamp. The four characters are, in order of biggest to smallest teacup: 礼, 乐, 射, 御, or li, yue, she, yu. They mean "rites, music, archery and charioteering" - these represent four of the Six Arts that were important to education and Confucian philosophy in ancient China. Because of their decreasing size, the four cups form a set that can be nested inside each other, with the lips all at the same height. These are the oldest Zisha implements that have been discovered to date, and the historical implications of this discovery are worthy of further exploration.

In September 2004, fourteen archaeological groups from throughout China came together to hold an academic forum at Nanjing Museum. They were also holding a large exhibition that was unprecedented for the time, and very educational. It was called "The Beauty of Clay: A joint exhibit of Purple-Sand clay pots from all around China, collected by the Chengyang and Nanjing Museum collections." The exhibition brought together 29 Zisha pots from the Ming and Qing Dynasties, found across seven provinces - Fujian, Zhejiang, Sichuan, Shaanxi, Shanxi and Hebei - and attracted a lot of attention in Purple-Sand clay scholarly circles. It was an unprecedented research opportunity to have so many exemplary Ming and Qing pots all gathered together in one place, with accurate dates and archaeological records. Of special interest were the seven Da Bin named Zisha pots - from coarse to refined, they all had a great amount of research value.

A fine example is the Shi Da Bin Three-Footed Lid Pot discovered at the tomb of Lu Weizhen (盧維禎), dating to the 38th year of the Ming Wanli Emperor's reign (1610). This pot is widely recognized as a genuine article from the workshop of teapot artisan Shi Da Bin (時大彬). The pot dates to only 28 years later than the twin pots from Zhao Xizhang's tomb. The owner of the tomb, Lu Weizhen (1543 - 1610), was the vice minister of both the Ministry of Revenue and the Ministry of Works during the Wanli Emperor's reign. This Da Bin pot was discovered filled with roasted Wuyi green tea leaves, suggesting that the tomb's occupant was a tea drinker during his lifetime. The pot is reddish-brown in color, and made of quite finely blended sand. It's covered all over with tiny, glimmering specks of naturally occurring mica, and from close up you can see a blending of maroon and yellow shades. It was fired to just the right degree, and one can tell that the pot was encased in a saggar throughout firing - apart from the occasional small black fleck from the sand, the surface of the pot is very clean, and there are no imperfections caused by flames.

The pot's most distinguishing characteristic is its lid, which is clearly based on the shape of a bronze three-footed cauldron called a ding (鼎). The beautifully made lid is bowl-shaped with three little "feet" in the shape of halfclouds, allowing it to stand up when removed and set upside-down. When inverted in this way, the lid serves as a teacup; although the bowl-shaped part of the lid is not deep, its vertical sides mean that it can hold a suitable amount of tea. Due to the addition of feet, the lid doesn't have a knob on top, and since it can be used as a cup, it doesn't have any holes to let the steam escape. Now, one might think this would be a problem, but this Da Bin pot is designed for enjoying tea for one in quiet solitude - so, once the lid has been removed to use as one's teacup, what need is there for steam holes? It's very clever! Ming writer Feng Kebin (馮可賓) put it thus in his Notes on Tea (茶箋): "Small teapots are the most valuable; to each person, a teapot. Let each pour and drink for himself; in this way, the greatest delight will be found. Why? Because with a small pot, the fragrance will not dissipate, and the flavor will not be diminished."

From this we can see that this Shi Da Bin pot is not only beautifully made, but also forms an innovative and practical response to the needs of individual tea drinkers. In the center of the rounded lid there is a very small bump, invisible to the eye but detectable by touch. It's in the place where a knob would usually be, and is a trace left by the potters wheel used to make the round lid. Because of the physical "memory" of the clay, this small trace has remained after firing. On the spout, one can see a slightly protruding line down the center, and by looking into the spout, this line is also visible at its base, which suggests that the whole spout was molded in two halves, and then the left and right sides were joined together. This mold line is neat and subtle, taking a flaw and turning it into a feature, and giving the spout a character of its own. It really displays the fine craftsmanship and aesthetic of Da Bin. The base is made differently than usual; it has a rounded clay lip that echoes the curve of the lid.

When I was attending the 2004 Clay Teapot Academic Forum, I saw two fragmented teapot bases displayed by Mr. Zhang Pusheng from the Nanjing Museum that were of a very similar quality and also had the Shi Da Bin name stamped into the base. In terms of shape and craftsmanship, they were very similar to the three-footed lid pot. In addition, there's a Shi Da Bin straight-necked round teapot that has been passed down as a family heirloom, which also has a very similarly shaped base. Does this, then, suggest that there is some connection between these pots? Or does it simply reflect a trend in teapot-crafting techniques in the late Ming? This is certainly worthy of further exploration.

Da Bin pots have always been the main focus of study for Zisha scholars. In addition to the pots in the Clay Teapot Academic Forum exhibition, there's also another Da Bin pot that's often overlooked: the Da Bin MelonShaped Purple-Sand Clay Pot with Chrysanthemum Decoration, housed in the Liuzhou Museum collection. This pot is purplish-brown in color, made from coarse sand, and the belly of the pot is formed into rounded chrysanthemum-petal shapes. The base and lid are both shaped like chrysanthemum flowers, with a chrysanthemum bud-shaped knob topping the lid like a jewel. On one of the sections, the Da Bin name is engraved in the clay. The National Cultural Artifact Classification Group, directed by Mr. Geng Baochang (耿寶昌), has classified this pot as a First-Class Artifact. Very early in the history of Chinese pottery, we saw Jin Wen (筋紋) pots shaped like lotus flowers begin to appear, thanks to the influence of Buddhism, and from historical documents we know that Yixing Purple-Sand clay pots in this shape were also around from the beginnings of Yixingware in the midto late Ming Dynasty. According to the first volume of the late Ming Yangxian Teapot Series (阳羡茗壶系) by Zhou Gaoqi (周高起), "Master Dong Han (董翰), also known as Hou Xi (後溪), has begun to make flower-shaped pots, which require a lot of skill to craft." Not long afterwards, masters such as Shi Da Bin and Xu Youquan (徐友 泉) also made flower-shaped pots. As recorded in Yangxian Pottery (陽羨 陶說) by Zhang Yanchang (張燕昌): "Government officials and nobles are very fond of drinking tea. I tried a little Shi Da Bin pot, shaped like a water caltrop flower with eight sections, with the maker's name on the side. One can easily lift and replace the lid, thus sealing the whole pot." Personally, I find the chrysanthemum-embellished shape of the Da Bin Melon-Shaped Purple-Sand Clay Pot to be quite unusual, and it certainly merits further research, especially the influence it had on future pots.

As well as the Da Bin pots, the Clay Teapot Academic Forum exhibition offered many other fascinating artifacts. One example is the gorgeous Chen Yongqing "Round Pot," unearthed at the tomb of Liang Weiben (梁維本) in Hebei Province's Zhengding County, and dating to 1650, the seventh reign year of the Qing Dynasty Emperor Shunzhi. The body of the pot is made from very finely worked purple clay, and the overall color of the pot is a blend of purplish-brown and yellow. It is perfectly fired with no blemishes, and the surface has a slightly granular effect, with fine yellow-brown speckles, almost like the skin of a pomegranate. This pot was made using a wide array of tools, and is so finely crafted that it is indistinguishable from modern-day Yixing pots; it, no doubt, represents the pinnacle of craftsmanship in the late Ming and early Qing. On the base, four characters are engraved that read "Made by Chen Yongqing (陳用卿制)." The neat, evenly shaped characters are laid out pleasingly in two rows; the knife-strokes are clearly defined and have a vigorous quality. In another volume of the Yangxian Teapot Series, Zhou Gaoqi mentions the master craftsman Chen Yong qing: "He makes many finely crafted shapes, like lotus seeds, round water kettles, alms bowls and round balls. They are perfectly round, without using a compass, and are very beautifully decorated. The maker's signature is in the style of Zhong Taifu's script; the master foregos the clumsiness of ink, and instead carves his mark with a knife." (Zhong Taifu, also known as Zhong Yao, is a calligrapher from the Three Kingdoms period credited with developing the "standard" style of Chinese script, known as Kaishu, which is still used today). We also have this record in the Essay on Yangxian Teapots (陽羨茗壺賦) by Wu Meiding (吳梅鼎): "Everyone says that Yong qing's decorations are richer and finer than any other." The Chen Yongqing "Round Pot" fits these descriptions very well: It is perfectly round, finely crafted and of excellent quality, with exquisite decorations; the characters in the craftsman's signature really do resemble the calligraphy of Zhong Yao, and are carved with a knife. Judging from this, we can infer that the round pot discovered in Liang Weiben's tomb is indeed a genuine Chen Yongqing piece.

From this research, it becomes clear that by the late Ming Dynasty, the craft of Purple-Sand clay teaware had already reached maturity, and master craftsmen like Shi Da Bin and Chen Yongqing had attained a level of skill and artisanship that was equal to that of today's artisans. So, when considering the development of Zisha pots from the standpoint of crafting techniques, it's true that one can see an overall increase in skill level throughout history; however, it's also worth noticing that every now and then, throughout history, a truly masterful craftsman has created a design so outstanding and ahead of its time that it breaks this pattern altogether, and forges an entirely new path in the long journey of Yixing Purple-Sand. From purely utilitarian works to functional art, Yixingware has achieved the pleasant blend of art and craft, form and function, more than any other ceramic tradition. The craft of Yixing truly does combine and harmonize the Heavenly with the Earthly realms!

The biggest event in the field of Zisha in recent years was the excavation of the old kiln site at Shushan. It was the largest excavation of Purple-Sand clay in history, and the soil strata uncovered in the dig spanned more than 300 years, from the late Ming Dynasty until 1966. It has provided an important foundation for determining the time period of Yixing clay ware for scholars both present and future.

The unique nature of the finds at Shushan deserve a special mention; most of the artifacts unearthed there were fragments of pots rejected by the kiln workers over the years and cast aside into piles of "seconds" beside each dragon kiln. These layers of failed pots give us an insight into the habits of the ancient potters - they were careful and fastidious workers; since the pots had quite a high market value, the craftspeople upheld high standards of quality during firing. In Zhou Gaoqi's late Ming Yangxian Teapot Series, the author writes: "For the finished piece to become elegant, it must be fired for a long time. Five or six pieces of pottery are put in the kiln and sealed up tightly. At the beginning, the pots may crack and damage the glaze; if the pot is fired too long, it will become too 'old' and will lose its aesthetic; if it's under-fired, it will be too 'young,' and the sand will remain coarse and unrefined." Because the potters were so careful, the rate of failure in firing the pots was quite low. If a pot was rejected, it would be thrown into a convenient pile beside the kiln, to avoid the possibility of the pot being copied. Here's an example of Li Dou (李鬥) talking about master potter Shi Da Bin, excerpted from the Yangzhou Pleasure Boat Journals (揚州畫舫錄): "While the pot was in the flames, he would wait attentively to take it out. If it turned out fine and elegant, he would crow with pride; but if he was not satisfied with it, he would smash it at once. Sometimes he would only keep one pot for every ten he broke. Every pot that was deemed unsatisfactory was smashed." According to this account, then, among the tens of thousands of pottery fragments excavated at the Shushan kiln site, it may be possible to identify some pieces of works by the great masters - but it would certainly require a generous dose of serendipity!

Even so, the piles of fragments unearthed at Shushan have a wealth of information to divulge, and are worthy of further investigation. A couple of interesting examples are the Damaged Sprinkled-sand Pot found in the early to mid-Qing stratum at the Shushan excavation site, which is identical to a surviving pot that has been passed down as a family heirloom, the Large Sprinkled-Sand Double Hoophandled Pot. In addition, another damaged cylindrical pot was discovered, whose shape and crafting techniques are strikingly similar to those of the Cylindrical Purple-Sand Clay Pot from the Chengyang Foundation collection that was imported to Sweden prior to 1785. The inlaid metal ornamentation that can be seen on this double hoop-handled pot was added after it arrived in Sweden; from the inscription on the metal handle, we learn that the metal ornamentation was added in 1785 in Stockholm, by a silversmith named Peter Johan Ljungstedt.

From the end of 1997 to the early spring of 1998, the Tangcheng Archaeological Group carried out two excavations in the old part of Xuzhou city, on the south side of Da Dongmen Street. During the excavation, they cleared out six ancient wells from the Qing Dynasty soil strata, unearthing a significant number of blue-and-white porcelain cups and plates, along with several dozen Zisha pots, soup spoons and other implements. Of these, around ten of the Purple-Sand clay pots were discovered more or less intact. According to Li Jiuhai (李久海), the director of the Yangzhou Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, an analysis of the blue-and-white porcelain indicates that the artifacts found there span a long period during the Qing Dynasty, from the reign of the Kangxi Emperor to that of the Jiaqing Emperor. The evidence suggests that the site is probably the remnants of a Qing Dynasty tea house.

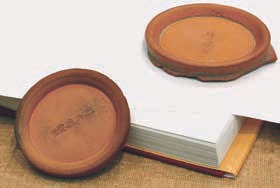

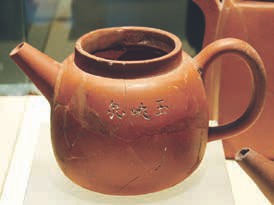

This group of pots are mostly quite practical in shape: round, with straight spouts. The bodies of the pots mostly have sand mixed into the clay, and display a variety of colors, including reddish-brown, vermilion red, dark brown, and even black or the pale yellow of osmanthus flowers. Several of the pots carry inscriptions in standard Kaishu (楷書) script, reading "Yu Xia (玉峽)" or "Jade Gorge," and "Yu Xia Quan (玉峽泉)," "Jade Gorge Spring." Because most of the pots have lost their lids, only one remains with a square seal stamped onto the bottom in relief, with characters of the Zhuanshu (篆書) seal script style. The seal reads "Yuan Zhang (元章)," "Original Seal." There's another spherical short-handled pot that also shows traces of the square maker's seal, but the characters are hard to distinguish. There are also two four-sided pots that bear the words "Made by Jing Xi (荊溪所制)." It's worth noting that a number of Zisha pots bearing this same inscription on the lids were found on the wreck of the Tek Sing, which sank in the twelfth month of the first year of the Daoguang Emperor's reign. Although the seal on the two sets of pots was not imprinted using exactly the same wooden stamp, the style of the Zhuanshu characters is similar enough to verify the authenticity of the two pots.

The Yangzhou Archaeological team also made a noteworthy discovery on a construction site at the Yangzhou Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital. It was a lidded Purple-Sand clay bowl that bears a round and a square seal beneath the lid, reading "Jing Xi (荊溪)" and "Made by Zhang Junde (張君德制)." It is finely crafted, with an elegant round shape. Coincidentally, an identical lidded Zisha bowl with the same seal was displayed at the San Francisco Asian Art Museum in late 1977. It came from the collection of Laurence Sickman and appeared in an exhibition entitled "I-Hsing Ware," curated by Ms. Terse Tse Bartholomew (謝瑞華). There are a few scattered records of Zhang Junde, which indicate that he was a Qing Dynasty potter who worked with Purple-Sand clay during the reigns of the Yongzheng and Qianlong Emperors. Among the red clay or zhuni (朱泥) pots, there's a pot bearing the mark "Junde," with a wide belly and a curved spout, that is commonly known as the "Junde Pot." The Illustrated Study of Yangxian Sand Teapots (陽羨砂壺圖考), written by Zhang Hong (張虹) and Li Jingkang (李景康) after the establishment of the Republic of China, contains the following passage: "There is a teapot with very fine craftsmanship, which is inscribed with just two characters in standard Kaishu script: 'Jun De.' The Bishan Teapot Museum collection also contains a small red clay Junde pot. It has a double layer of glaze, and is stamped on the bottom with four characters meaning 'Made during the years of Yongzheng (雍正年制),' also in Kaishu script." Could this mean, then, that this Junde is in fact Zhang Junde, and that the vessel came to be used for gongfu tea due to the fame of the artisan who made it? This has yet to be verified with more research.

There are a few surviving Zisha pots and tea-leaf canisters that are decorated with colorful scenic paintings. This style of decoration can be seen on pots from the Qianlong and Jiaqing periods of the Qing Dynasty, such as the Wang Lun Pot with Scenic Paintings that was discovered in a tomb from the Qianlong period. Another example is the Jingmei Qingxiang Pot with Scenic Paintings, discovered in Shanxi Province in a tomb dating to the fifth reign year of the Jiaqing Emperor. The Wang Lun pot was discovered in 1959, in a tomb from the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, in Banshan, Hangzhou. The body of the pot is red-brown in color and is shaped into four petal-like segments, with a short, flat-topped spout. The sides are decorated with paintings, and the knob on top of the lid takes the form of two painted peaches. The maker's stamp appears on the underside of both pot and lid, and features the name Wang Lun (王倫) in Caoshu (草書) cursive script. There is also an oval-shaped stamp featuring some indecipherable characters in the Zhuanshu seal script. Although the Zhejiang Museum has identified the Caoshu characters on the bottom of the pot and lid as reading "Wang Lun," I believe it's very likely that these characters were simply an identifying mark commonly used by the artisans who painted the pots, as this mark is very commonly seen on surviving painted Zisha pots. So there probably wasn't an actual person named Wang Lun.

Among the items unearthed in the same tomb were two Purple-Sand clay water pots (used for calligraphy). One of them was the Purple-Sand Clay Many Fruits Pot. Similar "Many Fruits" pots can be seen in various collections, such as the Chinese University of Hong Kong's Art Museum and the Suzhou Museum. Most of them are signed "Ming Yuan (鳴 遠)." From this, we can tell that these water pots featuring fruit and nuts, such as walnuts, peanuts and water chestnuts, had already appeared in the late Qianlong period. Another interesting piece from the Hangzhou tomb is the Purple-Sand Clay River Snail Water Pot. Another pot of this same shape is housed at the Musée National des Arts Asiatiques Guimet in France, and bears the inscription "Made in the ninth year of Kangxi's reign, at the Maoyuan guesthouse," as well as a small, teapot maker's stamp with only the character "Yuan (遠)." Another of these pots resides at the Hong Kong Teaware Museum, again marked with the name "Ming Yuan," while yet another one is housed at the Nanjing Museum, this time stamped with the characters "Shi Min (石民)." Pei Shimin was a potter working in Shanghai in the 1920s and 1930s, who produced many copies of Chen Ming yuan's pieces with exquisite care and craftsmanship, and was widely reputed as "the second Chen Mingyuan." Evidently, when Master Pei made his Purple-Sand Clay River Snail Pot, he had a solid foundation on which to model his work.

As for the Jingmei Qingxiang Pot with Scenic Paintings that we mentioned earlier, this was discovered in December of 1975, in Shanxi's Xiangfen County. Scholars believe that the tomb it was found in belonged to Liu Wenhu (劉文虎), who, during his lifetime, served as the prefectural magistrate and was buried in the fifth reign year of the Jiaqing Emperor. It shows no traces of use and was likely a new pot made especially for the burial. The Jingmei Qingxiang name is often seen on red clay gongfu teapots, and the discovery of this pot gives credence to the theory that several known maker's marks found on these red clay pots date to the late 18th century. As well as Jingmei Qingxiang (競媚清 香), these include Jingxi Meiyu (荊溪 美玉), Siyan Shexi (肆筵設席), Gaopeng Manzuo (高朋滿坐) and Yuzan Huangliu (玉瓚黃流). These names tend toward the poetic, and roughly mean: "Charming Fragrance," "Jing Creek Fine Jade," "Four Bamboo Mats Set for a Tea Ceremony," "Surrounded by Honorable Friends" and "Liquor From a Jade Libation Cup."

In the history of Zisha-ware in the Qing Dynasty, two potters stand out as the most renowned in the field: the Two Chens, namely Chen Mingyuan (陳鳴遠) and Chen Mansheng (陳曼生). Many teapots by the Two Chens survive today, though small misfortunes befell some of the excavated pots. Firstly, let's take a look at the Chen Mingyuan pots. One example, the Mingyuan Forty-third Year MidSummer Ancient-style Pot, was unearthed at the tomb of Lan Guowei (藍 國威) at Chiling township in Zhangpu County, Fujian Province. The tomb dates to 1756, the twenty-third year of the Qing Qianlong Emperor. Lan Guowei (birth date unknown) sat the Imperial Examination in the sixtieth year of the Kangxi Emperor's reign and went on to hold a military position in the light cavalry. Also unearthed at his tomb were several other pieces, including a porcelain tea tray decorated with ink paintings of scenery and people, four small white-glazed blueand-white porcelain teacups decorated with flowers and marked with the name "Ruochen Zhencang (若琛珍 藏)" or "Precious Collection," and a hexagonal tea leaf tin - inside the tin were tea leaves and a slip of paper with the brand name, "Su Xin (素心)," written in ink. Together with the red clay teapot, these items form a full set of implements for a gongfu tea session, which suggests that the occupant of the tomb was a gongfu tea enthusiast. The pot was discovered completely intact, but unfortunately, due to the inattention of the villagers who discovered it, the spout was broken off and lost during the excavation process, which is a pity indeed.

Because this pot is the only one of Chen Mingyuan's Zisha pots to be discovered in a tomb with a definitive date, researchers are quite certain of its age. Because of the inscription on the pot that refers to the "Forty-Third Year Midsummer," scholars have determined that it was made in 1726, the fourth year of the Yongzheng Emperor's reign (this was the forty-third year of the sixty-year Chinese calendar cycle). I had the fortune to examine this pot up close during the 2004 Clay Teapot Academic Forum exhibition at the Nanjing Museum. I observed that it was crafted with great skill and care, even and precise, using very fine clay with a silky-smooth texture. When picked up, it felt solid and steady in one's hand. It was remarkably different from ordinary finely made red clay pots; it truly is a masterpiece worthy of the famed Ming Yuan name. On the other hand, the shape of the pot and style of the maker's mark are indeed quite a typical example of what one usually sees with red clay gongfu teapots, and Chen Mingyuan was, after all, praised in the annals of Purple-Sand clay as a master craftsman whose pieces were sought at home and abroad. Until more examples of Chen Mingyuan's work are discovered, we should perhaps leave some room for consideration as to the pot's identity.

As for the other of the Two Chens, Chen Mansheng, one of his pots was collected by the Shanghai Museum in Jinshan County in 1977. This is the Purple-Sand Clay Bamboo Joint Pot, which bears the mark "Wan Quan (萬泉)," "Ten Thousand Springs" and is signed with Mansheng's name. This pot is significantly different from other surviving Mansheng pots, and there are many opinions, both positive and negative, about this pot, all of which contain a kernel of wisdom - so we won't go further into that here. Another noteworthy teapot was discovered in January of 1986, in Hexia Village, in the Chuzhou District of Huai'an city, Jiangsu. This was the Peng Nian Three-Footed Cauldron Pot, discovered in the tomb of Wang Guangxi (王光熙). The identity of Wang Guangxi is unknown, but from all the other artifacts uncovered in his tomb - a Da Bin brand Zisha pot, some white-glazed floral teacups from the kilns at Dehua, cloisonné water pots for calligraphy, and thirty-one different seal stamps, including some made from valuable bloodstone and larderite and decorated with carved lions - we can tell that Mr. Wang was a scholar and a lover of tea.

This Three-Footed Cauldron Pot is a classic example of a Mansheng piece. A fourteen-character inscription is carved into the shoulder of the pot in a free, vigorous script, reading: "With the light of the Tai Ding constellation, one may live to be as old as Zhangcang; this three-footed pot was made by Mansheng." Tai Ding (台鼎) was the old name of a constellation named after a Ding (three-footed cauldron), and is thus a metaphor for the three-footed teapot, and Zhangcang was a historical figure known for living a long life; so in other words, the gist of the poem is that making one's tea in a good Purple-Sand pot can aid one to live a long life! The bottom of the pot bears two seals, Peng Nian (彭年) and Xiang Heng (香蘅); both sets of Zhuanshu seal script characters are stamped in relief. Xiang Heng is Mansheng's eldest son Baoshan (寶善), also known as Xiao Man (小曼), "Little Man." According to research by Mr. Huang Zhenhui (黃振輝), the location where this pot was excavated is the same as the station in Liyang where Mansheng was appointed to oversee river conservancy works; plus, the seals on the pot are in Mansheng's handwriting; from this Mr. Huang infers that this pot dates to the 25th year of the Jiaqing Emperor's reign, at the latest. The Peng Nian indicated on the pot is Yang Pengnian (楊彭年), who was one of the main teapot craftsmen at Mansheng's workshop. He was also considered one of the masters of his generation and many Peng Nian Zisha teaware pieces survive today. According to Qian Yong's (錢 泳) Lu Yuan Collection, as well as being famed for the skill of his family-run workshop in his own era, Peng Nian's works were imitated far and wide for generations to follow. In my opinion, the Peng Nian signature on this Peng Nian Milk Cauldron Pot does indeed appear to be the standard seal of Yang Pengnian, and can verify the pot's identity. To borrow the words of Zhou Gaoqi, it's "sufficient to settle conflicting opinions." Also worth mentioning here is a pot that was included in The Elegance of Purple, which was recently published in Taiwan: the Xiang Heng brand Mansheng "Hundred Patchwork Robes" Pot. This pot was originally from the collection of Qing Dynasty diplomat Gong Xinzhao (龔心釗); it is accompanied by a burl wood box, which Mr. Gong has carefully labeled by hand on the outside. The lining of the box also bears many stamped collector's seals and a note written on a piece of paper; together they form a very precious set of artifacts. The pot is small and delicate in shape, and its surface is decorated with a subtle blend of yellow-, red- and brown-colored clays, as splendid as the sunrise. The body of the pot is inscribed with these words: "Do not look down upon rough clothing, for beneath it there is wisdom; which pours out with a lively sound. Signed, Mansheng." The particular garment referred to in the inscription is a shuhe (裋褐), a type of short jacket made of coarse material, which is a metaphor for the pot; so the sentiment advises us not to judge people (nor teapots!) for their appearance, as wisdom may be found in both tea and the words of others. The underside of the handle is stamped with the Peng Nian seal. The bottom of the pot bears a long Xiang Heng seal, which is identical to the one on the Peng Nian Three-Footed Pot that was found in Wang Guangxi's tomb, so these two pots serve to confirm each other's authenticity and to accurately date the find and all the pieces therein.

In Taiwan, too, some Purple-Sand clay pots have been discovered. In 1999, the National Museum of Natural Sciences undertook an excavation of some ruins at Bantou village (板頭村) in the Hsinkang township in Taiwan's Chiayi County. This area used to be called Bengang (笨港), and was one of the earliest areas established by the Han Chinese, and one of Taiwan's most important and bustling ports during the Qing Dynasty. The ruins at the excavation site were the remnants of the Qing Dynasty local administrative offices of Zhuluo County and Bengang County. Because the nearby Beigang Creek was prone to serious flooding, parts of the town were often submerged or damaged over the years by the changing waters, resulting in a great number of Qing Dynasty artifacts being buried underground in the area. Scholars have determined that "Although we cannot rule out the possibility that some of the pieces may trace back to as early as the Yongzheng Emperor's era, the newer pieces certainly date to no later than the reign of the Jiaqing Emperor."

Among the items excavated were twelve Purple-Sand clay fragments, which are believed to come from four separate teapots. Among these is a bamboo joint pot which, after being restored using surviving pots as a reference, bears a striking resemblance to another bamboo joint pot that was excavated from the wreck of the Geldermalsen. The first pot is almost perfectly round in shape; the lid has been lost, but we can speculate based on similar pots that the knob on top may have been shaped like the mythical three-legged golden toad, or like a curved piece of bamboo that is similar to the handle and spout. The second pot is shaped into an elongated, slightly rectangular shape, with curved sides and rounded corners. Another of the broken pieces looks to come from a pomelo-shaped pot, and has part of a line of poetry inscribed on the bottom with the maker's mark (with some blanks where the characters are missing):

"A pavilion in the moonlight ___ ___ person; Meng Chen (亭月□□人, 孟臣)." This mark is commonly seen on pots that have been excavated or passed down through the generations in southern Fujian. Other pottery pieces were found with the inscriptions "Made during the years of Qianlong (乾隆年制)" and "Made by Pan Zi___ (潘子□制)." I believe that the Zisha pots unearthed at the Bantou village ruins likely date to before the period of the Qianlong Emperor.

Underwater excavation techniques have allowed archaeologists to expand their reach from land to sea; to uncover traces of human civilization from deep beneath the oceans. Over the centuries, these underwater museums have silently guarded their records of human exploits from all sorts of places and time periods: sea transportation, trade missions, cultural exchange, even wars and plundering.

According to the estimates of archaeologists from around the world, there are currently more than 16,000 known shipwrecks with cultural and historical significance scattered throughout the world's oceans, with the majority located in Europe. In the Asian region, the majority of shipwrecks can be found in the oceans of Southeast Asia; according to the research of U.S. historian Dr. Roxanna M. Brown, between 1974 and the present, more than 120 shipwrecks have been discovered in the seas of Southeast Asia. This area is commonly known as the South China Sea, and has had close political and trade ties to China since ancient times. It has also acted as the main thoroughfare for travel between the East and the West, and as a strategic hub for international trade and shipping. Of course, the myriad relics buried in shipwrecks beneath this maritime section of the Silk Road have become precious resources for those who study the history of trade, culture, art and crafts. They form a fascinating microcosm of the economic development of seafaring societies.

Unsurprisingly, the relics discovered in these waters have included a large amount of pottery. This is, of course, partly due to China's famed skill in producing beautiful ceramics, with international demand resulting in a flourishing pottery trade over many generations. However, the other reason is that the physical properties of pottery allow it to weather the conditions of the sea floor for long periods of time and still largely retain its original condition. By studying the pottery contained in shipwrecks, researchers can not only determine things like cargo stacking methods, the vessel's route and the nature of the merchandise, but also make inferences about other cultural and economic circumstances, such as the skill level of the artisans wherever the pottery was produced and the tastes of the overseas market where it was headed.

In recent years, academic circles have achieved some fruitful results in the field of maritime archaeology, with findings proving significant to the study and dating of cultural artifacts. Findings from archaeological excavations in the South China Sea have garnered particular attention and are generally met with great anticipation. As for the pottery discovered in the seas of Southeast Asia in the last few years, there is no shortage of Purple-Sand clay implements; however, since we only have the space of one article, I shall outline some of the finds from several noteworthy shipwrecks in the passages that follow.

From 2004 to 2005, a company by the name of Nanhai Marine Archaeology Sdn. Bhd., founded by Swedish underwater archaeology expert Sten Sjöstrand, undertook an important excavation in partnership with the Malaysian government. The project was located six nautical miles offshore from the Tanjong Jara Resort, in the province of Terenganu on Malaysia's west coast. They salvaged the wreck of what is believed to be a Portuguese cargo ship dating to the reign of the Ming Emperor Tianqi (around 1625). The ship most likely sank due to an accident en route from Guangzhou to the Malaysian state of Melaka (Malacca). The majority of the recovered artifacts were ceramics destined for overseas sale and dating to the reign of the Ming Emperor Wanli; because of this, Sjöstrand named the ship "The Wanli." There were very few Purple-Sand clay pots found aboard - the only pieces recovered were three teapot lids and two broken pottery fragments, all from round pots. One of the lids features a "pearl" style knob, set like a gem in the middle of a twelve-pointed star shape, which is decorated with a ring of spiral patterns stamped into the clay. These pieces are the earliest known Purple-Sand clay pots to ever be discovered on an underwater excavation site.

In 1991, a team assembled by the University of Cape Town, South Africa, began to dredge the wreck of the Oosterland in Cape Town's Table Bay. The Oosterland belonged to the Dutch East India Company and sank in 1697, the 36th year of the Emperor Kangxi's reign. The artifacts uncovered include six entire Purple-Sand clay teapots destined for the overseas market and several dozen fragments. This group of teapots has two distinguishing characteristics. The first is that the six intact teapots all bear seals identical in style to those found on pots intended for the local Chinese market; however, some of the pots are decorated with auspicious patterns molded onto the surface, which was obviously intended to cater especially to Western markets.

In 1985 United Sub Sea Services, headed by British-born Australian resident Michael Hatcher, discovered and dredged the wreck of this Dutch East India Company ship, which sank in January 1752 (the twelfth month of the Qianlong Emperor's sixteenth reign year). The artifacts uncovered from the Geldermalsen included more than 150,000 pieces of blue-and-white porcelain, 125 gold ingots weighing 750 grams apiece and about ten Yixing Purple-Sand clay teapots. Some of these teapots went to the collection of Hong Kong's Flagstaff House Museum of Tea Ware; those pots are likely familiar to Purple-Sand clay enthusiasts in Taiwan and mainland China. Among them is a six-sided pot, whose lid is ornamented with a lion holding a ball, a shape that was also noticed among the damaged pots found at the Shushan excavation in Yixing discussed earlier in this article. So it seems that this style of pot was popular both in China and abroad during the Qianlong era.

The lion-shaped knobs on these pots were usually formed by using a wooden mold to create the basic shape, then adding carved details afterwards. On the finer examples, the artists have really captured the details of the little lion's musculature and shaggy coat, right down to the delicately patterned ball that jingles when shaken. There's a charming innocence about them, and they were very popular on the market, with a great number being transported to Europe. The spout of the six-sided pot from the Geldermalsen is a "triple-bend spout (三灣流)" formed from four adjoined pieces. The surface of the handle is also four-sided, and features a small knob on the upper edge. The reason for the knob is that this shape of pot is very heavy - the lid, in particular, uses more clay than usual and is prone to toppling off when the tea is poured, which is why one sees quite a few pots where the lion has lost its ball. So, the addition of this small knob on the handle helps the pourer to hold the pot steady. This design feature has been noted on silver and gold pots dating back as early as the Tang Dynasty.

Another of the finds was a pearshaped red clay pot, which is the only gongfu teapot discovered on the Geldermalsen. However, the lid is a little small and is suspected not to be this pot's original lid, which implies that there were other pots of this shape on board. The maker's mark on the bottom is carved rather than stamped, and reads "Yu Xiang Zhai (玉香齋)," or "House of Fragrant Jade." There is no other record of this mark, but there is another known pear-shaped pot which bears a similar mark in the same carved handwriting, namely "Yu Zhen Zhai (玉珍齋)" or "House of Precious Jade," so it appears likely that these two pots are related.

In 1999, Hatcher discovered another wreck, this time in the waters off the northern coast of Java: The Tek Sing, which sank in the twelfth month of the Daoguang Emperor's first year in power (January 1822 on the Gregorian calendar). Discovered on the ship were tens of thousands of ceramics and gongfu teaware pieces, among which were two to three hundred Purple-Sand clay teapots, mostly red clay or zhuni (朱泥) gongfu teapots, obviously intended to be sold to the Chinese community in Southeast Asia. There are as many as ten different shapes of pot, spanning all the main types of gongfu teapot. In terms of shape, they all belong to the basic category of round pots; the spouts are mainly of the "single-bend (一灣流)" and straight variety, which are the most efficient for pouring tea. Only a few of them, such as the Si Ting (思亭) pot, feature the traditional "double-bend (二灣流)" shape of spout. The handles are mostly thick at the top and thinner near the bottom, round both inside and out, with a visible joint where they meet the body of the pot. The majority of the lids are of the "placed lid" or yagai (壓蓋) shape, where the lid has a slight outer lip of the same diameter as the lip of the opening, so that the lip sits directly on top of the teapot mouth when placed there. Second most common is the "cut-off lid," or jiegai (截 蓋), which has a curve that smoothly follows the curve of the rest of the pot, so that it looks like the teapot and lid were originally one sphere with a line cut around to remove the lid. Finally, the least common is the "inlaid" style qian'gai lid (嵌蓋), where the lid is inset to be completely level with the top of the opening. The knobs on top tend to be shaped like a miniature version of the pot itself, the top echoing the bottom; this is a traditional design concept of Yixing pots. The teapot bases are mainly of the "circular foot (quanzu, 圈足)" and "false circular foot (jia quanzu, 假圈足)" styles, with just one pomelo-shaped pot that has a concave base, or yina di (一捺底). From the inside, one can see that these pots were fashioned according to the traditional "cylindrical body" or "da shentong (打身筒)" technique, where the clay is first formed into a tube. Although the pots have been worked using pottery tools, there are no obvious tool marks; there is a single steam hole in the knob of each lid, which forms an internal trumpet shape, narrow on the outside and wide toward the center of the pot.

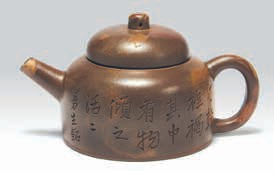

The pots are largely made from red zhuni (朱泥) clay, with the occasional zini (紫泥) purple clay pot (these colors of clay all belong to the general category of "Zisha," Purple-Sand clay - as mentioned earlier in this article, despite its name, Zisha clay can display several different colors, ranging from reds and purples to dark brown, black and pale yellow-green). Overall, the crafting techniques are completely consistent with those of the red clay teapots found in Qing Dynasty tombs across southern Fujian in the last twenty years. They are all from Yixing and are typical examples of classic gongfu teapots. Most of the teapot bases are inscribed with lines of poetry, using a bamboo or metal knife, and are stamped with a seal bearing the raised characters "Made by Meng Chen (孟臣制) in Xingshu (行書)" in running script. Some of the pots bear a seal consisting of seal-script characters with no border, imprinted using a wooden stamp, such as the one pictured here, which reads "Moonlight shines among the pine trees; made by Meng Chen (明月松間照; 孟臣制)." This same mark has also been found on pots unearthed in Minnan, southern Fujian.

Unique among the pots found on the Tek Sing was an unusually large Zisha pot measuring 18.5 centimeters high and 32 centimeters wide; it was probably a personal possession of one of the passengers or crew members. Despite the ocean deposits that have built up on the surface, one can still observe that this pot is made from fine purple clay, and the overall shape has a natural sense of elegance. Although the relevant records do not specify the brand name of this pot, from what we know of similar surviving pots, we can infer that this one very likely has the maker's name stamped on the bottom, and we even have a good idea of whose name it is: one of the potters from the Shao (邵) clan, of whom there were several in Yixing, including Shao Hengyu (邵亨裕), Shao Daheng (邵大亨), Shao Xumao (邵 旭茂) and Shao Youlan (邵友蘭), all masters working from the Ming to Qing period. Most known pots of this design are large ones with a capacity of two to three liters, and generally bear the name "Jing Xi" ("Jing Creek") along with the potter's name, most commonly "Jing Xi, Shao Yuanxiang (荊溪 邵元祥)," "Jing Xi, Shao Yumi (荊溪 邵旭茂)" and "Jing Xi, Shao Xinglong (荊溪 邵形龍)." Though they vary in quality, these teapots are largely similar in shape; they are mostly sidehandle pots, though there is an occasional hoop-handled pot, too. The main characteristics of these pots are their wide, thin handles, rounded on the outside and flat on the inside; as well as their spouts, which are especially big and wide in the middle, like a crab's claw. Of the thousands of shapes of Yixing pots, this is one of the rarest styles ever found.

The Zisha pots found on the Desaru bear around thirty different maker's marks. Aside from a few that have the traditional Meng Chen mark, there are also the following: "Made by You Yumi (有餘秘制)"; "Made by You Lanjian (友蘭監製)"; "Zhouchun Huitang (周春輝堂)"; "You Yi (友 義)"; "Wen Yuan (文元)"; "Tang Po (湯婆)"; "Made by Shao Yuanqi (邵 元麒制)"; "Made by Yi Yijian (宜邑 蔣制)"; "chashu xiangwen (茶熟香 溫)," meaning "the gentle fragrance of mature tea"; "shou (壽)," meaning "Longevity"; and "buke sheng duiji xin (不可生妒忌心)," meaning "One must not have a jealous heart." There are also several maker's marks in the form of decorative auspicious patterns or pictures - this was a common style in the Jiangnan region. In summary, we can surmise that this group of pots are a synthesis of Jiangnan-style Purple-Sand clay teapots and gongfu teapots from Fujian and Guangdong: they combine elements of teapot styles from both regions.

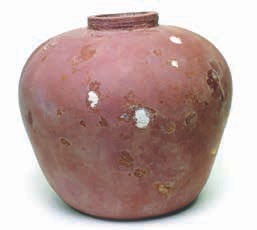

Of particular note is the fact that the teapots found aboard the Desaru were stored in several dozen Yixing clay jars of varying sizes; the space between the teapots was packed with rice husks and other similar grains to protect the pots. The industry around manufacturing everyday Yixing pottery items has been well-developed since ancient times; there are over 3000 different variations of pots, jars and urns, which were produced in large numbers. It's not really surprising that the crew of the Desaru would use Yixing pottery urns to pack Yixing Purple-Sand teapots; however, this teapot packing method has apparently not been seen on any other shipwrecks. Among the many different pottery jars, there is a batch of Yixing pottery "dragon urns (龍缸)" with raised decorations on the surface. Dragon urns are also known as "four-dan dragons (龍四石)," which refers to their capacity - a dan (石) was a measure of grain equal to ten dou (鬥). Pottery jars were classified according to their capacity, for example a "seven-dan jar" or an "eight-dan jar."

The appliqué style of decoration on these urns is literally called "sticking on flowers, (tie hua, 貼花)," or "piling on flowers, (dui hua, 堆花)." This method uses multi-colored clay produced in Yixing as "ink," allowing the artist to decorate the surface with flowers, birds, scenery, people and animals. Once the clay is stuck onto the surface of the unfinished pot, it is worked with the thumbs, using five main techniques: pushing, rolling, "walking," pressing and tearing (拓, 搓, 行, 撳, 撕). On the appliqué dragon urns discovered on the Desaru, we see auspicious decorations, such as lions playing with balls, bats and trees, including pine, bamboo and plum blossom. The same subject matter and decoration can also be seen on the Qing Dynasty appliqué dragon urns that people like to collect today. These Yixing dragon urns are an embodiment of cultural values during the Ming and Qing dynasties; all sorts of auspicious motifs appeared again and again in art from all over China, with artists doing their utmost to include symbols of good fortune and happiness. There's a saying that encapsulates this ethos: "Art must have meaning, and meaning lies in the auspicious."

The materials presented in this three-part article on the archaeology of Purple-Sand clay are, of course, limited to these pages and to my own experience; there are many areas where it would be possible to go into much greater detail. There are many other Purple-Sand clay pots of beauty and significance housed in museums and public and private collections in China and abroad that are also worthy of study; alas, it is not possible to list them all here. Nonetheless, I hope that the information I have been able to include will be of some benefit to readers interested in Zisha ware.

As we conclude this article, special thanks are due to the Taipei Chengyang Arts and Culture Foundation (臺北成陽藝術文化基金會), whose help contributed to the discovery and research of some of the archaeological finds mentioned in this article. The Chengyang Foundation's close collaboration with many museums and cultural history organizations in recent years has contributed significantly to expanding the depth and breadth of research in the field of Purple-Sand clay. In the future, there are plans for this type of collaboration to extend beyond China to the rest of the world; I'm sure that this will come as happy news to fellow enthusiasts of Purple-Sand clay art around the world.