|

|

Puerh tea is a part of everyday life in the Cantonese regions of southern China, so it has its own corner in the tea market. However, with today's puerh craze, there's a tendency to blindly chase after traditional sheng or "raw" puerh products, such as "un-aged" tea or "Pure Green" puerh cakes - everyone seems to have forgotten that the vast majority of puerh in the market is actually "ripened" shou puerh. In Hong Kong's puerh tea culture, shou puerh is the most widely known, and is the commonly accepted definition of puerh tea. Because of this, whenever someone lauds puerh as a rare, valuable tea, people tend to be mystified, even more so by the high prices it can fetch. This is because when most Hong Kongers think of puerh, they think of the cheap, low-grade drinking tea that is served to accompany ordinary meals in Hong Kong's restaurants. Nonetheless, shou puerh is still generally considered a good choice of drink, as long as it's not too rough in quality. In this article, I shall present an exploration of shou puerh tea culture in Hong Kong, with the hope of offering fellow tea lovers a glimpse into this unique side of shou puerh.

Forty years ago, Hong Kong was very different from the large international metropolis that it is today, founded on its financial and service industries - back then, it was still an industrial city. From the 1950s to the 1970s, Hong Kong was just developing as an industrial city, and the living conditions were poor. Many households were composed of blue-collar workers who didn't have the financial means to taste expensive teas, so the practice of drinking tea for tea's sake alone was not very common. Tea leaves were considered an everyday part of life, something that you offered your guests to show courtesy. A household would usually have a pot of tea at the ready, not only for the convenience of the family members if they were thirsty, but also so they could greet guests with a hot cup of tea, as a sign of the family's good manners and hospitality.

In the early 1950s, the Chinese government implemented land reforms, with specific policies affecting landowners and wealthier peasants. Ownership of all land, livestock, farming equipment, surplus grain supplies and buildings was transferred to the state. Land formerly rented out by the wealthier farmers was taxed and distributed among the less well-off farmers and sharecroppers. The result was that land-owning classes were basically eradicated. Because of this, many former landowners and their descendants from Chaozhou in Guangdong left their homeland, due to a dearth of work in the countryside, and migrated to Hong Kong, which, at the time, was still a British colony. They brought an aspect of their tea culture with them to Hong Kong, namely Chaozhou-style gongfu tea (潮式功夫茶).

Chaozhou people were accustomed to drinking gongfu tea after eating to "dissolve the grease" of a meal. So, Hong Kong tea merchants catered to the tastes of their customers and mainly sold teas typically used for this purpose, such as tieguanyin and Cliff Tea. Many immigrants from Chaozhou also opened tea shops of their own. So, although drinking puerh was not yet very popular in Hong Kong at the time, there was already a strong underlying foundation of tea culture.

In this new millennium, we carry around devices that allow us to make a phone call or connect to the Internet in an instant, so interpersonal communication is very convenient - all we need to do is tap out a message or press "call." But we ought to recall that in Hong Kong several decades ago, only commercial enterprises had the financial resources to install a telephone. And from the 1950s to the 1970s, telephones were the only type of communications technology available. So, if you wanted to meet with your friends for a chat, tea houses were an important part of the equation. Discussing business and socializing with friends all took place in traditional Hong Kong tea houses, which served tea and dim sum. Thanks to the importance of tea houses in the social lives of Hong Kongers at that time, the consumption of tea began to rise.

Up until the 1970s, the most common teas served in Hong Kong's tea houses were Shui Xian (水仙), a Wuyi oolong whose name translates to "Narcissus" or "Water Fairy," Tieguanyin (鐵觀音) and a white tea called "Shou Mei (壽眉)." These types of tea were brewed in a gaiwan (lidded teacup), which meant that each guest had their own personal vessel to brew and drink their tea. This way, you could brew your tea to your own liking - as soon as it had reached the desired strength, you could pour it out or drink it, with no need to over-brew. During that era, many traditional tea houses still used gaiwan; even today, some restaurants, such as the Lin Heung Tea House (蓮香茶樓) still use gaiwan. At that time, people didn't go to restaurants in a family group, as prior to the 1970s, it was still fairly uncommon for women to work outside the home or have much of a public social life. This meant that the patrons were generally men out to discuss business deals and socialize - so gaiwan were perfect for this type of scenario. In the '70s, however, the situation began to change.

From the late 1960s to the early 1970s, Hong Kong's economy was booming, and there were plenty of jobs to go around. There's a saying from the time that describes this state of economic prosperity: "Even grannies are out cutting threads." (In other words, even such small jobs as trimming threads were picked up by grandmothers who didn't even know anything about dressmaking!) So, as the saying illustrates, it was very easy to find a job and earn money.

As a result, many women went to work in Hong Kong's factories, which supplemented the family income (in those days, it was common for families to have six to eight children). Because of this, many families found themselves a lot more well-off than before, so they now had the spending power to go out to restaurants for dim sum. After a week of hard work, many families chose not to make breakfast on Saturdays and Sundays, instead, heading straight out to a restaurant for a dim sum "brunch" to save themselves the trouble of cooking. As a result of these societal changes, from the mid-1970s, restaurants or jiulou (酒樓) serving food and alcohol became much more common in Hong Kong, outnumbering the more traditional tea houses or chalou (茶樓).

Thus, social occasions where each person had their own gaiwan slowly transformed into large family gatherings to celebrate free time together. Many tea houses gave up on using gaiwan to brew tea, as they took up a lot more table space with the three pieces required to make up one gaiwan; on top of that, children didn't know how to use them and risked breaking them. So in the end, these restaurants changed their brewing methods to better suit large family groups. They started using big teapots, which could easily brew several cups of tea and didn't need topping up with hot water as frequently as gaiwan. So large teapots inevitably became the vessel of choice in these new restaurants. As we discussed earlier, the most common teas in Hong Kong's tea houses were Shui Xian, Tieguanyin and Shou Mei - in the days when they were still being brewed in gaiwan, this was just fine; however, this new era of large pots presented a new problem. With large teapots, it wasn't convenient to pour out all the tea straight away, and people dining out in Hong Kong were accustomed to letting their tea steep, rather than separating the liquor from the leaves. The problem, then, was that teas like Shui Xian, Tieguanyin and Shou Mei become stronger the longer you brew them, so the first two brews of a pot would be very bitter and astringent, while the next few brews would be weak and insipid. So, the restaurant owners began to purchase large quantities of Yunnan puerh, recommended by the tea merchants who had shipped it over. Puerh tea offered the following advantages:

Thanks to these benefits, once puerh appeared in tea houses, it quickly spread across Hong Kong and became well-known among ordinary people. Of course, this isn't to say that puerh was completely out of favor with tea connoisseurs, but simply that it entered the collective consciousness via Hong Kong's tea houses, and more and more Hong Kong people came to learn of its existence.

Hong Kongers have a special word for going out to have tea; as well as using the ordinary verb "drinking tea," there's also a phrase that means "enjoying tea": tancha (嘆茶). The word tan literally means "to sigh" or "to exclaim." Throughout the history of Hong Kong's dining and drinking culture, there have been various, different types of establishments, all with separate functions: "tea house" style restaurants; restaurants serving food and alcohol, literally "liquor houses," shops serving cold drinks and other restaurants. But as the lives of Hong Kong people grew busier, it became more convenient if one establishment could offer multiple types of food and drink, so traditional tea houses that served tea on its own gradually began to decline, due to all the competition and were replaced by restaurants and taverns. Many of the old-style tea houses were no longer able to stay in business, and one by one they closed their doors. But, as they say, every cloud has a silver lining: The closure of these old tea houses meant that as their storehouses were cleared out, a number of rare and precious antique puerh tea cakes once again saw the light of day. This resurgence led to the flourishing market for old puerh that we see today. So, the development of puerh is inextricably linked to these changing historical circumstances.

These traditional old tea houses placed a great importance on the quality of the leaf, as several decades ago in Hong Kong, there wasn't a great variety of drinks available to choose from: mainly just tea, alcohol and coffee. There weren't any of the soft drinks and other flavored beverages that are common today. To ensure the quality of their tea, these old-style tea houses would employ a "tea supervisor" who was responsible for overseeing the tea buyers. For a tea house, supervising the purchasing of tea leaves was extremely important, since different grades of tea leaves had different flavors, and the price of tea varied a lot. To be successful at blending the different teas, one had to understand how to use the right proportion of sheng and shou leaves, as well as how to find a balance between price and quality. To do this well required depth and breadth of knowledge. As a result of this process, tea blends from the different tea houses all tasted slightly different.

Perhaps this explains why many of Hong Kong's older tea drinkers would faithfully show up at their favorite tea house every morning for their first cup of the day! It's a pity that today's tea houses mostly forego this carefully thought-out process in favor of using leaves that are all the same grade. Traditional tea houses also had a position called the "Tea Doctor" or cha boshi (茶博士), whose job was to carry a large copper pot to refill everyone's hot water - since the tea was mostly brewed using individual gaiwans, it needed refilling often. This takes a special skill that is recognizable to those in the know. They can spot the time for refilling even from afar.

Originally, the puerh served in Hong Kong's tea houses was made from high-quality loose-leaf tea from storehouses with good conditions. In the 1980s, however, the tea houses didn't have enough puerh to keep up with demand, so lesser quality puerh that has been stored in underground warehouses started to hit the market. This led to the widespread impression that puerh tea has a moldy flavor to it. As a result, someone had the idea of adding chrysanthemum flowers to the tea to mask this moldy taste, which started a trend for drinking chrysanthemum-flavored puerh, or jupu (菊普). Later on, however, there was a rumor that drinking chrysanthemum-flavored puerh over long periods was bad for the health, so the number of people who chose to drink this jupu tea decreased dramatically.

It's said that many of the early stamped tea cakes were made to order for the tea house owners. This is a reasonable theory, since according to the recollections of tea professionals from the older generation, a few decades ago, there wasn't much retail demand for tea cakes, and you wouldn't normally see them sold individually. They were usually bought wholesale in large batches by the tea houses that used them to blend tea. So at the time, people wouldn't usually use puerh cakes at home.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, since these disc-shaped tea cakes, or cha bing (茶餅), were mostly bought by the tea houses and didn't fetch a high price, in the eyes of retailers, they were all but worthless. They were variously described as "round tea," "troublesome tea that you have to break up before drinking," "tea that consumers don't really want to buy" and "a product that won't sell." So, before Taiwanese Chajin began arriving in Hong Kong in search of puerh, most of the tea shop owners were in the habit of breaking up the low-value sheng tea cakes and blending them with shou tea. This was quite understandable, as this extended the patience of the sheng tea. It also enhanced its sweetness, as well as reducing the odor of the shou tea, so the two complemented each other well. In fact, Hong Kong people in general have never warmed to very young sheng puerh, as it's too hard on the digestive system.

So, for the above reasons, sheng puerh cakes have never been too popular in Hong Kong. In the '80s, many Yellow Mark cakes that had been aging in storage were broken apart and blended with other teas, before being sold off cheaply for drinking. Twenty or so years ago, tea shop owners did their best to avoid sheng puerh cakes, so no one ever imagined that twenty years later they would see such a resurgence in popularity, where supply could no longer meet demand and prices practically rose by the day. The reason that so many puerh cakes were preserved in Hong Kong was due to their low price and suitability for blending to stabilize the flavor and quality of the puerh. This was why Hong Kong's tea merchants were willing to invest money and warehouse space on these unglamorous tea cakes. So those puerh cakes that were originally intended for brewing up in large pots were slowly refined by the passing years, until they rose like the proverbial phoenix from the ashes to become a precious tea that people were falling over each other to buy. This all came as a great surprise to the owners of the tea houses and shops!

Because very young sheng puerh was never widely accepted in Hong Kong, in the 1970s, when tea merchants were ordering their tea, they always specified that they wanted shou puerh. Sheng puerh cakes were so unpopular that they were almost regarded as a kind of parasite. In order to get rid of the sheng puerh cakes as quickly as possible, wholesalers would feign ignorance and surreptitiously stick a couple of tubes of sheng puerh cakes into each shipment of shou puerh (the tea cakes were usually packed in bamboo tubes, or tong, 筒). Although, at that time, the retail tea merchants' concept of sheng and shou puerh was still somewhat murky, each time they unpacked a shipment to sell the individual cakes, they would notice that some of the cakes were hard as stone and unpleasant to drink. They didn't really know what to do with these hard cakes, so they would either return them to the wholesaler or ask them not to send any of these hard cakes in the future! As a result, 1970s wholesalers still didn't have a good way of dealing with their sheng puerh cakes.

But tea merchants need to make a living, too - who on earth would be willing to store tea for more than a decade before they were able to recoup their costs? What's more, no one could guarantee that the tea would actually sell in more than a decade's time! Some tea merchants at the time knew that some of the early loose-leaf puerh sold to restaurants and tea houses had been "soaked" in Changzhou, that is to say, that some sort of fermentation technique had been used to "ripen" sheng puerh into shou puerh - this seems to refer to the process of piling, or wo dui (渥堆), to oxidize the tea. But of course, the technique for this "soaking" process was a trade secret, so the merchants, not understanding tea production methods, could only think of recklessly exposing the tea cakes to humid storage conditions, without properly considering the degree of humidity, in the hopes of maturing the tea more quickly. The merchants referred to this process as "underground storage," since these humid warehouses were often underground.

Hence, a great volume of unsaleable sheng puerh cakes were taken to these underground storehouses, in the hopes of finally being rid of them and making a quick profit. However, it's some of these stamped puerh cakes that were stored by tea houses that have been preserved the best, since the tea was only being kept for the tea house's own use, and there was no pressing need to sell it. This also explains why many of the surviving tea cakes, such as Zhongcha Jianti (中茶簡體), "China Tea" cakes with simplified characters, or Xiao Huang Yin (小黃印), "Small Yellow Mark" Seven Sons cakes, have suffered some serious damage due to humid storage conditions. Although compressed tea cakes were not generally well known in the '70s, there were a few high-level tea connoisseurs who sought them out expressly. Since selling tea cakes made a healthy profit - higher than for loose-leaf tea - and since the merchants knew that they could increase the price with the right fermentation techniques, they began to import tea cakes in large quantities. Since their aim was to make a profit, they also chose relatively cheap sheng puerh cakes to put in storage, because the cost of shou tea cakes was usually around 20% higher. To their surprise, after a few years of storage, the tea still had the same young, green flavor - it didn't seem to have changed at all. On top of that, it wasn't popular to drink puerh from compressed tea cakes in the '70s - there was almost no market for it. So these sheng tea cakes just kept on piling up in the storehouses of small tea merchants.

Although tea dealers at the time didn't have a clear concept of sheng and shou puerh, they did understand that storing those round tea cakes in underground warehouses would make them marketable, so this kind of storage became more and more popular. This led to the development of so-called "Hong Kong-stored" puerh, with its distinct flavor. In the early days, the merchants importing the tea were really going through a process of experimentation. Some smaller-scale merchants took the hard, sturdy sheng puerh cakes that were threatening to swamp their warehouses and, as a last resort, tried using high humidity to oxidize the cakes, in the hope of selling them more quickly (these were most likely China Tea and Yellow Mark cakes). So, as time went on, Hong Kong's tea merchants developed a more defined concept of puerh tea: Namely, that it needed to be aged in storage to achieve a sufficiently smooth, rich flavor and mouthfeel. And of course, the most important factor was that only with this kind of aging could puerh tea fetch a good price.

Now, don't be fooled into thinking that there are many ordinary households in Hong Kong that mainly drink their puerh in the form of tea cakes. I myself, as a puerh lover from Hong Kong, can tell you that most families still mainly consume inexpensive loose-leaf puerh. I would even say that, aside from those well-versed in the art of tea who have a special interest in puerh, most puerh drinkers in Hong Kong don't even really know about puerh cakes in any of their various shapes, be they disc-shaped bing (餅), bowl-shaped tuo (沱) or brickshaped zhuan (磚). Most people only know of loose-leaf puerh and don't buy cakes for everyday drinking, as they're inconvenient to break up, and people don't know how to do it. Cakes also tend to be more expensive than looseleaf puerh.

The loose-leaf shou puerh found in Hong Kong has two different origins: There is puerh made from genuine Yunnan leaf, and another type made from Vietnamese tea leaves. Vietnamese leaf is generally cheaper, and the tea that results from it is not very patient, and has a very subtle sour taste to it; who knows, perhaps this is a distinguishing characteristic of tea from across the border!

In the '70s, some merchants were already wise to the fact that aged puerh could appreciate, because during the buying process, they noticed that when they bought tea from the same batch two years apart, the price had gone up the second time - even though it was from exactly the same batch of tea! So, they started to look ahead and view the tea like money in a savings account - if it stayed in the wholesaler's warehouse, it would sell for more in a couple of years' time anyway; from the merchants' point of view, it made more sense to buy it now and store it themselves, so they could be the ones to collect the "interest" after the tea was sold. So, some of the smaller merchants started aging the tea in their own storehouses. Tea sellers of that era were very pragmatic; they had long been in competition with each other to do business in their local neighborhoods. Now, they needed to be able to sell puerh for an extended period of time. Although in the '70s the retail market for puerh tea wasn't exactly red-hot, a part of the population still drank it, so every two years, a merchant would need to buy around ten large sacks of loose-leaf puerh. In the first year, they would sell the first five sacks, keeping the other five until the following year so they could collect the extra profit from the rising prices. At the end of the two years, they would buy another batch of young, low-priced tea to replenish their stocks for another two years, and so on. Over time, a tea-storage cycle was formed.

Another reason why the tea merchants needed to store the tea themselves was that this loose-leaf tea had all been stored in damp, "underground warehouse" conditions. Buying it in large quantities meant that the merchants could then store it in their own clean and less humid warehouses to "recover." As time passed, they realized that this tea that had been taken out of "wet" storage in this way would become richer and more mature over time. Eventually, it became clear that the longer puerh was aged, the higher a price it would fetch. The looseleaf puerh sold in Hong Kong is also known for its naming conventions: The merchants in Hong Kong would sell the tea under product names that they created themselves, rather than using the original factory numbers from Yunnan. Although each tea merchant had a different method for choosing the names, certain names would only show up among very high-grade aged puerh. For example, more valuable puerh would be called things like Zhen Cang (珍藏), "Collector's Treasure," or Bu Zhi Nian (不知年), "Year Unknown," to indicate that they had been aged for a very long time, improving with the years.

I have personally compared several loose-leaf shou puerh teas, which you can find in the accompanying table. Throughout this process, I noticed that those teas which have undergone "underground storage" are more pleasant to drink, and more closely resemble the aged Yunnan puerh that most people are familiar with from Hong Kong's tea houses. Although the leftover leaves from brewing teas number five through eight contain some dark chestnut, almost black tea leaves, in my opinion, the teas that have been through underground storage have more of an aged flavor to them and are nicer to drink. Shou tea needs to have a long enough "recovery" time after being taken out of wet storage, in order to achieve a rich, harmonious flavor.

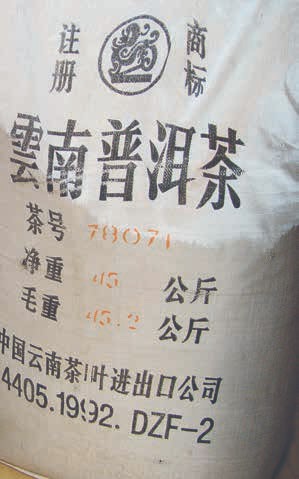

Although most Hong Kong households mainly consume loose-leaf tea over the years, there has also been a small group of tea enthusiasts who seek out puerh tea cakes. So Hong Kong's tea sellers still needed to have some shou puerh bing on hand to keep their customers happy. One excellent example of a classic Hong Kong puerh cake is the 1988 vintage 7432 tea, which comes wrapped in thick brown paper. This tea's full code number is 7432 - 804. The first four digits denote the year the recipe was first invented, followed by the leaf grade and factory code. The second set represents the production year and batch number - 804 means that this was the fourth batch produced in 1988. It's an excellent tea that exhibits all the characteristics that a good shou puerh should: It's pure, aged, sweet, smooth and rich. It also displays a hint of sheng puerh character, namely a subtle sweet aftertaste.

According to the tea shop owner, this is because it contains a relatively high proportion of sheng tea and was not made entirely from shou tea, so when it was first produced, it wasn't overly pleasant to drink. So the original tea merchant had to put it into underground storage, in order to sell it more quickly. But because it was left to age for an unexpectedly long time, the sheng component in the tea was influenced by the storage conditions, and ended up producing a flavor close to that of shou puerh. This was how the tea shop owner put it, at least. In any case, whether it is completely shou tea or half sheng and half shou, this batch of 7432 - 804 tea is very worth drinking by today's tasting standards.

Whether because of the weather or some other factor, 1992 was an excellent year for shou puerh. Whether it be '92 vintage 7542 tea, '92 small tea bricks or '92 Xiaguan First Grade tuocha, all display a great flavor. Any shou puerh from 1992 that has come out of underground storage produces a ginseng fragrance when brewed, and an astonishing flavor that encompasses the five classic characteristics: pure, aged, sweet, smooth and rich. The only thing it lacks is the bright liveliness of sheng tea, but as a shou tea, it exceeds expectations. For someone who mostly drinks aged sheng puerh cakes, this tea was a pleasant surprise; it's easy to drink and is an excellent tea for those who are starting out in their puerh tasting journey. These cakes are handwrapped in tissue paper, and the whole batch is notable for the absence of large nei piao (內票) or identifying tickets, usually included inside the packaging.

Another quite well-known variety of shou puerh cakes are Purple Sky cakes. Apparently, there are quite a lot of imitations of this tea on the market. I acquired this tea quite by chance, and I haven't been able to uncover any definite information about its background. However, judging by the original paper wrapping and nei fei (內飛), the small identifying ticket embedded in the cake, I believe it probably dates to the early 1990s.

Puerh tea has developed to such heights today, not just due to its memorable taste, but also thanks to the gentle and patient nature of shou puerh; it acted as the perfect teacher to guide early puerh students in their journey of discovery. If it weren't for shou puerh, sheng puerh cakes may have never become what they are today. So, while we go on tasting fine aged sheng puerh cakes, there's no reason not to include some shou tea, too. What's more, a good shou puerh has its own lovable qualities, and will certainly be more affordable than a sheng puerh cake of the same vintage. Shou puerh is a type of tea that is well worth appreciating and exploring.