|

|

Liu Bao is a town located in the Cangwu County of Guangxi. On Hekou Street of the town, there was an old camphor tree. Standing there, you can hear the river flowing gently. This tree and the river had witnessed all the changes that occurred throughout the hundreds of years in the town, and maybe they are willing to share with us all the tea stories of this tea town.

There have always been ups and downs for Liu Bao tea, and this is especially true during the last one hundred years. Many would describe these stories as tragedy. Yet, I believe you may be interested in reading such stories, which are not known by many. The following stories were either told by the elderly who live in the town, or extracted from the Records of Liu Bao, written in 1985.

In ancient times, Liu Bao was not a prosperous town. Residents in the town faced different problems, such as inconvenient transportation, and also a lack of doctors or modern medicine. Luckily, wild tea trees were not in short supply in this mountain area. One day, people in the town started cultivating tea trees, so that they could make teas for medical purposes and daily use. From what we heard from the folktale and saw from the genealogy records, we know the tea town had a population boom during the Ming Dynasty (1368 - 1644).

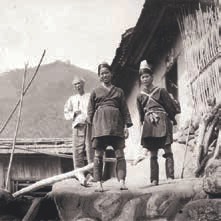

Part of the population growth was contributed by local citizens, whose heritage can be traced back to the Baiyue (百越) people. Since their ancestors had been learning the culture and knowledge of Chinese since the Qin Dynasty (221 BCE - 206 BCE), they were considered as Chinese people who had kept their local customs. Most of those citizens had been living in the Yao Village of Liu Bao. With several hundred years of experience growing teas, the Yao Village is still widely considered as a famous tea-producing village today. Another factor that contributed to the population growth during the Yuan Dynasty (1271 - 1368) and Ming Dynasty was that there had been many wars in China during the period. People were rushing to the mountains to escape from war, and many of them had been settling down in Liu Bao since then.

Yi Zhangqi, a Liu Bao resident who is also an expert in the history of Liu Bao, shared some of his findings. According to Yi, many of his ancestors were government officials in Cangwu from the late Yuan to the early Ming dynasties. The family later relocated to Liu Bao. At that time, the family relied on blacksmithing for their income. This implied that Liu Bao was already a densely populated town, likely with a well-developed agricultural sector to provide sufficient food for its residents. According to studies, the Wei and He families, two of the major families in Liu Bao, also settled down in the town during the Ming Dynasty. According to Chen Bochang, a tea expert in Liu Bao, his family was also relocated from the northern part of China during the early Ming Dynasty.

Being a mountainous area with wide valleys and pleasant climate, Liu Bao has been a producer of tea, bamboo, wood, firewood, fungus and mushrooms. Before the Yuan Dynasty, residents in Liu Bao had to produce everything they needed due to transportation barriers. Population growth created the soil for the handicraft and trading business to grow. The earliest traders in Liu Bao would use packhorses to transport the products, which were mainly necessity goods. Some markets were then naturally formed in densely populated areas during the late Ming Dynasty. Other than necessities, local products, including teas, were sold in these markets, sometimes taking the form of barter. At the same time, growth in population also boosted the agricultural sector. The handicraft industry, being an important supplement to the agricultural economy, had also been developing rapidly since then.

Teas were also being produced on a larger scale. The tea manufacturers adopted the steam-fixing method, which was used since the Tang and Song dynasties (618 - 907, 960 - 1276), to produce both tea cakes and loose-leaf teas. Even though the production of tea cakes using the steam-fixing method was no longer popular in the central parts of China during this period, tea producers in Liu Bao did not follow the trend. Instead, they insisted on using the traditional method to produce teas, mainly for locals who favored such tea. In fact, the tea-production methods and tools used in those days are still in use today.

According to Records of Liu Bao, the first trading business in the town was a grocery store established on Hekou Street by the Mo family. Teas, necessities and other local products were being sold in this store. As local demand for necessities (which were not produced in Liu Bao) kept increasing, some businessmen started trading necessities bought from other towns for the high-quality goods produced in Liu Bao. Naturally, many grocery stores also became tea dealers. Teas produced in Liu Bao at the time were mainly transported by sea and being sold in the coastal area of Guangdong. Many tea lovers in Guangdong, especially those who lived near the Xi River, were attracted by the strong taste of Liu Bao teas.

Deng Chengwen, a merchant in Guangdong, saw a great business opportunity in trading teas and other local goods produced in Liu Bao, after realizing that these products offered excellent value for money. After making a fortune through trading in firewood and tea, Deng built a large cottage in Liu Bao for his business and named it "The Wen's (文記)." Deng intensely studied the teas being produced in the town, and discovered that besides the strong taste, Liu Bao teas were also a popular medicine for indigestion and diarrhea in Yu'nan, Zhaoqing, Yunfu and other places. Since then, he purchased Liu Bao teas in large scale and sold them to the Guangdong market. The fact that Liu Bao sounded the same as "six fortunes" in Cantonese was also a reason why Liu Bao teas were beloved in the province.

Seeing the huge demand of high-quality teas in the Guangdong market, Deng decided to focus on the tea business three years later. Other than building a factory and a warehouse, he also hired local workers and experts in tea production from Guangdong. As he was not a tea grower himself, he also started purchasing freshly picked tea leaves from tea growers in Liu Bao. According to Records of Liu Bao, Deng's business had been producing Liu Bao loose-leaf tea and Lui An tea (六安茶) in the beginning. Later, tea leaves produced in the town were also used in the production of puerh teas. According to some senior Liu Bao residents, Deng's business would later classify his products into "Upper Grade," "Middle Grade" and "Lower Grade," with each product being sealed (which serves as a trademark) before selling in the market. At the same time, nei fei ("內飛," literally "inner trademark ticket") were also put into the teas produced by The Wen's. The inclusion of nei fei in tea products was considered an innovation at the time.

In fact, the growth of Liu Bao tea was largely due to Guangdong people. Some even say that Guangdong, especially the southern part of the region, provided the necessary soil for Liu Bao tea to flourish. Before Liu Bao tea became a star product, it was only consumed by the people in neighboring cities, and later, they were sold to Hong Kong, Macao and Southeast Asia countries. Most of the tea traders at that time were from Guangdong, and most of the teahouses established in Liu Bao were also owned by Guangdong residents. Since the Ming Dynasty, drinking Liu Bao tea had become a popular pastime for people in southern China, and this was especially true for Cantonese people. The huge demand for tea in this region made possible the large-scale production and exportation of Liu Bao tea. Many Cantonese people migrated to Southeast Asia during the late 19th century to the early 20th century, and they brought the habit of tea-drinking with them to foreign countries, partly due to the climate and working conditions in Southeast Asia countries. The production level of Liu Bao tea peaked by the Second Sino-Japanese War, which remains unmatched today.

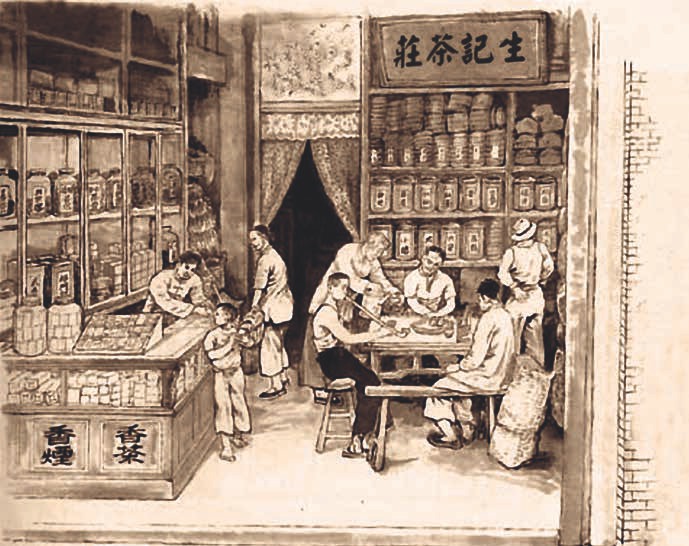

The success story of The Wen's and the increasing reputation of Liu Bao tea attracted tea traders to set up their business in the town. Shengfa (盛 發), a teahouse established by Liang, a Cangwu resident, was one of the first participants of the teahouse boom. Later, a tea trader from Heshan (a city in Guangdong) set up Sheng Kee (生 記), before many Guangdong tea traders from different cities would enter the tea business by setting up teahouses on Hekou Street. Some tea factories hired tea experts to collect tea leaves in Liu Bao during the spring, before transporting the raw materials back for production in autumn. Attracted by the potential, traders chose to establish an office in the town for convenience and to facilitate the movement of tea.

Owing to the geographical location, a foggy climate, ideal soil conditions and other factors, Liu Bao tea had a strong taste, which was beloved among tea drinkers. On the other hand, during the Qing Dynasty (1644 - 1911), the government officials had loosened its grip on tea production, and taxes were not as strictly implemented, which also contributed to the development of Liu Bao tea. Through word of mouth, drinking Liu Bao teas became increasingly popular among Guangdong people, who already had the habit of tea-drinking for more than 1,000 years.

Historical records suggest that people in Chaozhou and Shantou had been tea consumers since the Song Dynasty, and a large number of tea rooms were already in place during the Song and Ming dynasties. Facing the hot and humid climate in Guangdong, tea has long been seen as a refreshing drink among the grassroots in Guangdong. Since the Ming Dynasty, many tea houses were established in the markets for these people, and serving teas to customers had then become a must for every restaurant in the region. Since the 1850s, Guangdong people would go to the Yi Li Guan (一厘館, roughly translated as "1-Cent House"), which was a restaurant usually with only one table and four chairs, to enjoy a cup of tea and also a piece of cake. In front of the entrance of every Yi Li Guan, there would always be a wood sign with the Chinese character "茶 (tea)" written on it. In the 1860s or 1870s, Er Li Guan (二厘館, roughly translated as "2-Cent House"), a higher-end tea house, also started to appear in Guangdong, which made the trend of drinking teas in tea houses even more popular among Guangdong people.

Since the Ming Dynasty, teas were usually brewed in a large teapot. Even up until now, you can still see Guangdong people brewing teas in a large porcelain teapot, and you can still find those teapots being sold in the china-ware store. Shiwan (a town located in Foshan, Guangdong) was a teapot-producing town in which many Cantonese-style porcelain teapots were being manufactured. You can say that the huge consumption of Liu Bao tea among Cantonese people was largely attributed to the tea-drinking habit of those people. Without the ample supply of tea lovers in the region, the rise of Liu Bao tea may not have been possible. Since the 1850s, Liu Bao tea has been the standard choice of tea among many Guangdong residents. Other than having a favorable reputation, Guangdong people also like the strong taste of Liu Bao tea and its patience. In addition, many love Liu Bao tea because the brewed leaves won't turn sour when stored overnight.

From 1847 to 1880, many large tin mines were being discovered in Malaysia. Attracted by high wages, a large number of workers in Southern China, especially people in Guangdong, went to Malaysia and became miners. The climate of Malaysia was very hot and humid. Needless to say, the condition in the tin mines could only be worse. Many Chinese workers were suffering from vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal cramps before they were able to make a fortune. As it was widely believed that Liu Bao tea was effective in curing vomiting and diarrhea, many of the workers started drinking the Liu Bao teas they brought with them to Malaysia. As a result, they discovered that Liu Bao tea was not only effective in curing vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal cramps, but could also be used to relieve the symptoms of heat exhaustion. Liu Bao tea would then become a necessity for every Chinese tin miner. It was not only because of the medical use of the tea, but also due to the fact that Liu Bao tea was also an effective cure for homesickness. The popularity of the tea among miners boosted the production and exportation level of this magical medicine to Malaysia.

In the middle of the Qing Dynasty, the tea industry had become extremely vigorous. State-owned tea companies, local tea traders and foreign tea businesses were all establishing their offices in the Thirteen Hongs of Canton. The area had emerged as the major tea export center for foreign markets. As the cost of sea freight shipping was relatively low, Liu Bao tea, which was known for its great value for money, sold very well in foreign markets. Hence, more and more tea companies from Guangdong and Hong Kong went to Hekou Street to purchase tea leaves.

Most of the tea-trading facilities in the town of Liu Bao no longer exist today. It was due to the reformation of the tea industry implemented by the Communist Party, "The Campaign to Destroy the Four Olds." This is, of course, also known as the "Cultural Revolution," which changed all of China through and through, including architecture and tea. Most of the teahouses in Liu Bao did not survive these catastrophes, and a large proportion of those lucky survivors were demolished during the 1960s and 1970s.

The last tea-trading facility in Liu Bao was finally demolished in 2011. Local residents used to call this house "the tea kiosk." This house was built of bricks with tile roofs, located in a place called Ma Lian Ping (馬練坪). You could tell how big the tea-trading business in Liu Bao was by seeing how large the house was. The reason that this house could survive for such a long time was that it had been renovated and changed to be a residential house.

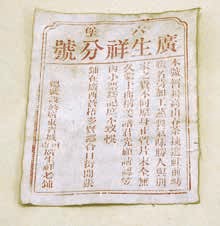

There were originally no walls when the tea kiosk was built. The roof was supported by brick pillars, making the building look like a Chinese-style kiosk. Tea growers could take a rest under the roof as they were waiting for the tea leaves to be received by the teahouses. Inside the house were the traditional drawings you would often see in a southern Chinese mansion. Even though most of the drawings were blackened by smoke, they were still recognizable before the kiosk was demolished. Like the Wen's, this kiosk was one of the earliest tea-trading facilities built in Liu Bao. The tea kiosk served as the tea-collecting station for five of the largest teahouses in the area, namely, The Wen's, Wan Sheng (萬生), Tong Sheng (同盛), Yue Sheng (悅盛) and Xing Sheng (興盛). Many tea traders from other cities and local small retail businesses were also collecting teas in the town, but these five teahouses were the first ones to set up tea-collecting stations in Hekou Street. In addition to being a tea-collecting point, the kiosk also served as the Liu Bao branch of Guang Sheng Xiang Teahouse (廣生祥茶莊), a famous tea company with a history of more than 100 years.

Chen Yongchang, a tea expert who has already passed away, was the late owner of the tea kiosk. I interviewed him for two times in 2006 and 2007, as he recalled the good old days of Liu Bao tea. According to Chen, the Guang Sheng Xiang Teahouse was established in 1669 by the Liang family in Nanhai, Guangdong. At that time, the owner of the teahouse was Liang Dingyuan, a father of five sons. The teahouse was profitable and had branches in Hong Kong and Heshan. Other than operating in the tea industry, the company was also trading other products.

At that time, Guangzhou was one of the ports opened for foreign trade, and tea was one of the products being exchanged. The Qing government set up many rules for foreign merchants, prohibiting them from entering the cities in China. Thus, foreign merchants could only purchase the tea leaves from local Chinese merchants, and it made the Thirteen Hongs of Canton, the Di Shi Pu (第十甫) and the Shi Ba Pu (十八甫) the export center of the tea trade. There was also a Guang Sheng Xiang branch in the Thirteen Hongs of Canton.

As mentioned above, many Chinese migrated to Southeast Asia during the middle of the Qing Dynasty, the sales level of Liu Bao tea in those countries, especially Malaysia, kept growing rapidly. As Liu Bao tea was becoming more and more popular in the market, its price had also increased. However, as the teas would often pass through several agents before arriving in Guangzhou, this business was not as profitable as the teahouses in Guangzhou wished. Facing this problem, Liang Tingfang, the third son of Liang Dingyuan and a clever businessman, decided to build a teahouse in Liu Bao. With the help of three employees, he finally set up Xing Sheng at Ma Lian Ping, which was actually a branch of the Guang Sheng Xiang Teahouse. According to Chen, the Liu Bao branch of the Guang Sheng Xiang Teahouse was established during the golden era of Liu Bao tea. At that time, Liu Bao teas were collected seven or eight times throughout the year. Essentially, tea leaves were almost being traded every day in the town. The turnover of the teahouse was great, and the business was highly profitable.

After living in Liu Bao for years, Liang Tingfang became a famous, well-respected person in town. Chen, a kid who often went to the teahouse to play, befriended Liang and would later be adopted as the godson of Liang. After growing up, Chen helped Liang operate the tea business, and he was mainly responsible for quality inspection. Years later, when Liang would go back to the head office during the New Year or other Chinese festivals, the tea kiosk was managed by Chen. As Chen began learning the craft of producing and reviewing teas at a very young age, he could easily tell the quality of teas by looking and smelling the dried leaves, no matter if the teas were produced in Shizhai, Xiaoshui, Daning, Wudong or Gaosuo. He could tell the value of the teas accurately, and he never made a mistake throughout his career.

As the sales of Liu Bao tea was high, Xing Sheng could no longer satisfy the market demand solely by purchasing teas from tea growers. Thus, the teahouse decided to enter the tea-production industry and started buying fresh tea leaves directly from the growers. Every morning, tea growers brought freshly-picked tea leaves to the tea kiosk. At noon, the tea kiosk was crowded with tea growers coming from different tea villages. During the peak season, part-time workers were hired for the production process. At the same time, experts in tea production were also hired, to ensure the quality of teas produced.

During this period, there was a famous tea-producing master called "Guo" working for the teahouse. He was able to create more than 20 variations of tea products that would taste differently, using the same batch of tea leaves! In addition to producing teas, Guo was also responsible for grading the tea leaves, and also packaging the final products before they were transported to Guangzhou. Other than loose-leaf teas, Xing Sheng was also producing so-called "Luopan tea cakes" (a Luopan is a kind of compass widely used in Daoist geomancy, called "feng shui"; the tea cake was called this because its shape looked like a Luopan) and "tea pillars." After completing the production process, a tea pillar would look like Hunan "Qian Liang" tea.

For tea pillars, bamboo strips were used to roll the tea leaves, in order to shape the tea cake. During production, several strong workers would step on the tea pillar and tighten the bamboo strips at the same time, in order to properly shape the pillar. After the tea was shaped, all the pillars were neatly organized in the factory, and Chen described this as a very beautiful picture. This whole procedure was very similar to that of Hunan Qian Liang tea - another kind of black tea.

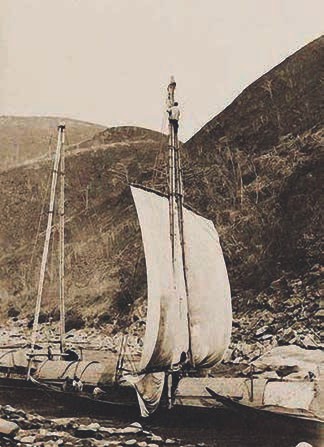

In Liu Bao, most of the products were imported and exported by sea. Products exported through sea freight would firstly be transported to Li Bao on a small bamboo boat, and the goods would then be exported to other cities through a larger wood boat. As more and more goods were being transported from and to Jiangkou, Ducheng and Guangzhou, the demand for wood boats also increased. Thus, there were finally 13 large wood boats used for transporting goods in Liu Bao. This route was often called the "Tea Boat Road."

In fact, there was also a "Tea Horse Road" in Liu Bao. The packhorses and porters, usually carrying tea leaves or local products of Liu Bao, would start their journey from the town, going to Xia Ying through the Du Village. The mountain road was steep and narrow, making it an extremely dangerous route. An old tea expert told me that the total distance of the "Tea Horse Road" was more than 130 li (里, or 65 kilometers). As the road was really steep, merchants had to rely on packhorses and porters if they were looking to transport their goods through the "Tea Horse Road." Besides this problem, there were sometimes robbers waiting for the porters! After arriving to Xia Ying, the goods would then be transported to Wuzhou by sea, and this was the easiest part of the journey.

Due to the increasing demand for necessities in Liu Bao, sea freight shipping, which was less efficient, did not have the capacity to transport all the goods. In addition to this factor, there was a large and active trading market in Wuzhou. All kinds of goods were being traded at reasonable prices in the market. Thus, many daily goods, including kerosene, salt, candy, biscuits, cigarettes and alcohol, were being transported by packhorses and porters from Wuzhou to Hekou Street. On the other hand, teas were also being transported from Liu Bao to Wuzhou through the "Tea Horse Road," in order to satisfy the demand for restaurants, tea houses and tea drinkers in the Wuzhou area.

The tea-drinking habits of the people in Wuzhou and Guangdong were essentially the same. Studies suggest that there were more than ten tea restaurants in Wuzhou during the Ming Dynasty, and this number doubled in the late Qing Dynasty. There were both high-end and low-end tea restaurants in the city, making both rich businessmen and grassroots able to enjoy a delicious meal with a cup of tea. Those low-end tea restaurants, serving lower-quality tea with dim sum, such as buns, were highly popular among Wuzhou residents. Along with supplying the tea restaurants, Liu Bao teas were also sold in teahouses and grocery stores.

My father, Peng Yaoguang, told me that my grandfather, Peng Qirong, opened a grocery store called "The Rong's (榮記)" outside the pier of Wu Fang Street. Aside from the store, my grandfather also operated a grocery boat. The boat would travel around the Guijiang River every day, supplying groceries, food and cooking oil, to people who lived their lives on boats. My grandfather's grocery business focused on selling the most popular teas: Liu Bao tea and Hengzhou fine tea. Hengzhou fine tea was rolled up in paper into a tube with a diameter of 5.5 cm and a length of 18 cm. Each tube would weigh about 0.25 kilograms. Unlike Hengzhou fine tea, Liu Bao tea was sold as loose-leaf tea. Customers would tell my grandfather the amount of tea they were looking to buy, and my grandfather would then wrap the tea leaves using paper. My father told me that some dishonest businesses would use some heavier papers to wrap the tea, so that the tea sold would appear to weigh more than it actually did. In contrast to those grocery stores, my grandfather operated his business honestly. He would only use light bamboo paper to wrap tea for his customers. As people found him trustworthy, his business easily attracted customers.

At that time, Liu Bao tea was affordable even for the grassroots. Even an average household would buy some lower-grade Liu Bao teas to drink. Drinking teas were so popular that teas were more often consumed than water in the town. Before the Second Sino-Japanese War, most tea lovers would only choose between Liu Bao tea and Hengzhou fine tea. The tea industry became much more interesting after the wartime. For example, oolong tea or Lu'an tea were also served in the tea restaurants after the war ended.

Liu Bao tea and other necessities sold in my grandfather's store were usually purchased from Sha Street, a place in Wuzhou where the wholesalers of grocery products gathered. Sometimes, people from the villages would directly carry rice, Liu Bao tea or firewood to my grandfather's store, and the goods sold directly by the villagers would usually be cheaper. It was likely that the Liu Bao teas sold by these villagers were transported to Wuzhou through the "Tea Horse Road." In order to avoid being robbed, merchants would usually pass through the "Tea Horse Road" together, along with the security guards hired from the martial arts center in Wuzhou.

In the Records of Cangwu County, it says, "There is good tea being produced in Liu Bao. The tea has a rich taste, and the brewed tea does not turn sour overnight. There is a tea called "Xiadou" tea ("蝦鬥茶," literally "shrimp fights with tea"), which has great color, aroma and also taste. The only defect is that its taste is a little bit thin."

According to Chen Yongchang, Xiadou tea produced by Xing Sheng was one of tea drinkers' favorites, even though Xing Sheng did not produce teas in large scale. The business earned its reputation through producing the best products among tea factories. In fact, the tea was not originally called Xiadou tea. Instead, it was called "Xia Tou" tea ("下頭茶," the words "Xia Tou" are a description of the location of Liu Bao). The mistake was made due to language barriers between Liu Bao people and Cantonese people, as their accents were much different. Anyway, Xiadou tea produced by Xing Sheng and Guang Yuan Tai, another teahouse in Liu Bao, quickly became famous.

The tea expert went on to tell me that Ludi, Gongzhou and Heishi were among the best tea production regions in Liu Bao. While high-quality teas were also produced in Lichong, Gongping and Shanping, teas produced in these areas were not as famous. In the northeast of Siliu, there is a mountain called Shuangji Mountain, which has an altitude of 750 meters. The teas produced in the valley of this mountain were highly appreciated by tea lovers. Chen told me that this tea had a strong yet mellow taste, and it had perfect color, aroma and taste.

In Liu Bao, there were even idioms praising how good the Liu Bao tea was. The teahouses in Guangdong and Hong Kong were almost looking to buy Heishi tea and Xiadou tea at any price, as these teas had already become very famous. Liang Tingfang of Guang Sheng Xiang investigated where the beloved Xiadou tea was produced. After realizing that it originated on Shuangji Mountain, he started purchasing the fresh tea leaves collected there. As Cantonese people were already used to the name of Xiadou tea, Liang did not correct this mistake even though it was incorrect and hilarious. At the same time, Guang Sheng Xiang was also producing Heishi tea with the fresh tea leaves collected in Heishi. The upper class in Guangdong loved the teas so much that there was always a shortage in supply. Since then, Xiadou tea and Heishi tea have become two household names in Guangdong.

The tea leaves used to produce Xiadou teas were carefully chosen. The leaves must be small, the stem must not be too slim or too short, and the teas must be collected at high altitude. The season and time in which the teas were collected were also important. In addition to these factors in choosing tea leaves, Chen also shared with me the production process of the tea, which is often considered top secret at a tea factory. At that time, all Xiadou teas were produced by Guo, who had his own way of baking, sha qing (殺青) and steaming. No one in the factory was allowed to see how he performed these procedures. Without knowing the tricks of Guo, it would almost be impossible to make a tea that would taste like Xiadou tea. Later, Guo had an apprentice, who would end up becoming his son-in-law. In the town of Liu Bao, there were only four people who knew how to make Xiadou tea. Besides Chen, Guo and also his sonin-law, there was also a tea master who worked at Guang Yuan Tai who knew the tricks of making Xiadou tea, although it was unclear how this man learned the craft.

Chen honestly told me that due to the increasing demand for the tea, there was a shortage in the supply of tea leaves. Thus, leaves from Siliu, Lichong and Buyi were later used to make Xiadou tea, and Guo would monitor closely the collection of the tea leaves and the whole production process. However, the procedures of processing the tea leaves remained secret, as the profitability of the tea factory heavily depended on it! The secrets to making Xiadou tea were kept for a long time. There was a tea factory that tried to bribe Guo with a couple of gold bracelets, and it was refused by Guo. Years later, Guang Yuan Tai, another tea house that operated in Hekou, was able to make a Xiadou tea that was very similar to those made by Xing Sheng. It was never known why Guang Yuan Tai was able to make Xiadou tea, but the fact was that their teas also sold very well in Guangzhou.

During 1944, Guo's son-in-law left Liu Bao with his family, as the Japanese army was attacking southern China, and he never returned to Liu Bao. In the 1980s, it was known that Guo went to Guangzhou, before finally settling in Hong Kong, and he never leaked the secrets of Xiadou tea. On the other hand, the tea master in Guang Yuan Tai, who knew the craft of making Xiadou tea, was killed by a bomb.

Chen also told me that Xing Sheng would place tea certificates in each tea basket, which was the standard procedure of Guang Sheng Xiang. In order to avoid counterfeit products, the production of tea certificates was closely monitored, especially for the certificate of Xiadou tea. The teahouse would try not to produce more certificates than its actual production level. In the case that too many tea certificates were printed, the teahouse would count the number of residual certificates, to ensure that no certificate was stolen by the workers.

The tea certificates, and also the seal, were no longer in use after the teahouse ceased operations. In the 1980s, they were all burnt by Chen, since he believed that they had no use other than occupying space. Almost 1,000 kilograms of tea leaves were burnt together, and it took a whole night for Chen to burn everything to ashes!

Chen also shared another colorful story related to Xiadou tea. In the late autumn of 1936, Chen Lianzhong, a senior manager of HSBC, sent a person to Liu Bao for Xiadou tea. He was looking to buy 50 catties (or 25 kilograms) of the tea for 60 dollars per catty, which was way higher than the market value. It was later known that Chen Lianzhong was looking to give the teas to some senior government officials in Guangzhou and Hong Kong, thus he was willing to pay a high price for genuine products. Upon receiving the order, Guo was puzzled, because there was not a single gram of Xiadou tea in stock! As Liang, the owner of the Xing Sheng, went back to Guangzhou at that time, he had no one to ask for help. After calming down, Guo came up with the solution.

On the one hand, he asked the workers to bring the person sent by Chen Lianzhong to the casino and also to the brothel. At the same time, he bought Xiadou teas from Guang Yuan Tai at a high price, and he asked the workers to change the packaging of the teas bought. After working overnight, Xing Sheng was able to complete this profitable transaction! The news of someone buying teas for 3,000 dollars was soon heard by everyone, making the tea more famous than ever before. According to the Records of Liu Bao, the town flourished through tea and local product trading activities, and there was a total of ten rich families living in the town. Thirteen mansions were built by these families.

The casino that I mentioned above was operated by Wei Zhuochen, the head of the Liu Bao organization. There were two branches of the casino in the east and west of Hekou Street. Traditional Chinese casino games like Pai Gow, Fan Tan and Sic Bo were offered in the casino. Many tea merchants and tea growers would test their luck at the tables. There was also an opium den inside the casino. Along with the opium smokers, there were also young ladies massaging customers.

Wei was a man of wealth who owned a large mansion in the town. Before opening the casinos, he operated three stores on Hekou Street. Later, he started the Yuji Bank. Along with offering money exchange services, the bank would also purchase gold minerals from miners, as there were such minerals under the Liu Bao River. Years later, the government instructed the Yuji Bank to issue silver certificates, with the nominal value of 10 cents or 20 cents. The silver certificates were widely used in Liu Bao and also in its neighboring cities, essentially giving Wei the ability to control the economy of Liu Bao.

As the town became prosperous through the rapidly growing tea trade, Wei opened two casinos on Hekou Street, and also a brothel. The brothel was extremely profitable, as it successfully attracted big spenders, such as tea merchants and other wealthy businessmen. The name and the location of the brothel are not known by us, and the Records of Liu Bao euphemistically call it a "club." According to the Records of Liu Bao, the banking, timber and gambling businesses were all making money for Wei. He invested part of the money he earned to build a ferry, which would then travel between Wuzhou and Hong Kong. It was estimated that he made 50,000 dollars every year from this new business.

As a mountainous area, the production level of rice in Liu Bao was not sufficient to feed all the residents, especially with the large inflow of workers on Hekou Street. Chen told me that more than 200 buckets of rice and other foods would be transported from Dongan Village to Hekou Street every day. Dozens of buckets of cooking oil and rice would also be imported to Liu Bao from Shuikou and Gonghui of He County. At that time, there were six food retailers with offices in the town, namely Ritai, Heli, Youxin, Zhongji, Yingji and Lisheng. Adding the many other retailers who did not establish an office in the town, you may imagine how active the trade was.

As Liu Bao tea and other local products (such as bamboo, wood and charcoal) became more and more popular in other cities, farmers' and tea growers' living conditions improved. Along with living a better life, they also had the resources to attract workers from neighboring regions (including Xiaying, Wangfu, Zhangfa, Shizhai, Shiqiao, Libu and other villages near He County) to Liu Bao. Most of those workers would either work in the tea industry (as tea growers or tea collectors) or the timber industry. At that time, all businesses in the town was going very well.

In the bamboo-producing villages neighboring Liu Bao, women would make bamboo baskets and then sell them to teahouses in Liu Bao. Sometimes, these craftsmen would also take orders from teahouses to make tailor-made baskets for them. There were also merchants from Hunan selling iron woks, iron pots, slashers, sickles and hoes. At the same time, these merchants would purchase salt, kerosene and other necessities from Liu Bao back to Hunan. Some traders would also buy resins in Hekou. The resins would need to be further processed before being sold in Guangdong. Many outsiders, especially the merchants from Guangdong, decided to open an office in Liu Bao as they were attracted by the business opportunities. Finally, there were merchants from Seiyap, Heshan, Yu'nan, Sanshui, Gaoming and Xinhui setting up offices in Liu Bao.

Besides the tea business, these merchants were also trading in bamboo and other local products. These offices were located in Hekou, Ma Lian Ping and Sanjie Zhou. An aged man from Jiu Cheng (a town in Liu Bao) told me that Jiu Cheng was also prosperous during this same period, not only because it was located on the Tea Boat Road, but also due to the fact that it was the starting point of bamboo and charcoal traffic. There were dozens of businesses operating there, including piece goods stores, candy stores and garment stores. Meanwhile, many people would take wood and bamboo to Jiu Cheng for further processing. For example, wood would be processed to make boats or charcoal, while bamboo would be used to make baskets, brooms, bags or other household items.

In addition to being a business center, Liu Bao had well-developed communication and business facilities, including a bank and also a post office. Goods were also being imported through the Tea Boat Road without hindrances. Chen Bochang, a tea expert, told me that his grandfather also opened a garment store in Jiu Cheng. Using a sewing machine imported from Germany, Chen's grandfather made and repaired clothes for the villagers. Different sources show that even though the Communist Party started ruling China in 1949, there was still a total of 27 garment stores, blacksmith shops, barber shops, shoemakers and other handicraft businesses in the town at that time. Also, there were 35 grocery stores, teahouses, medicine stores, restaurants, and hostels in the town during the same period.

As the competition between teahouses and merchants was fierce, tea merchants adopted different strategies, in order to ensure that they could buy the best possible Liu Bao teas. Some merchants would hire a "sub-owner" (essentially an agent) from Liu Bao, and they would rely on those agents to buy teas directly from the tea growers. According to Deng Zhaoming, the then-village head of Liu Bao, some of the tea growers would directly carry the teas with them and trade with the teahouses at Hekou. On the other hand, some teahouses and tea merchants chose not to establish a tea-collecting station. Instead, they would hire agents to buy teas for them from different villages. Of course, the agents would make a commission, both from the tea growers and the teahouses. There were also other teahouses that did not hire these agents. They would hire tea experts from Guangdong to value the teas collected by different tea growers. After agreeing on the price, tea growers would then deliver the teas to the teahouse in Hekou. Later, there would be some businessmen in Liu Bao, who were not originally tea merchants, who would buy teas from the tea growers. After that, they would rent a boat and ship the teas to Yunan, Ducheng or other cities in Guangdong for sale.

The production and sales volume of Liu Bao tea peaked by the Second Sino-Japanese War. Reputable teahouses that set up an office in a factory in Liu Bao included Hong Kong Tian Shun Xiang Teahouse, Guang Yuan Tai, The Ying's, Wan Sheng, The Wen's, Xing Sheng of Guang Sheng Xiang, Tong Sheng, Guang Fu Tai, The Xin's, Gong Sheng, The Sheng's, Yuan Sheng, The Yong's, Sheng Fa, etc. In addition, there were many small teahouses, sole traders and merchants who did not establish an office in the town. Statistics showed that between 1900 and 1940, goods exported from Wuzhou were mainly aniseed, pigs, tin, wood, pine and tung oil. It proves that most of the Liu Bao teas were not exported through Wuzhou. Instead, teas were transported to Guangzhou through sea freight, before being delivered to Hong Kong, the re-export center.

Shen Chang Zhan, a tea factory in Southeast Asia (which produced the famous Four Gold Coins Tea and Double Gold Coins Tea), also claimed that it had set up a tea-collecting station in Hekou in 1912. However, I was not able to confirm this through asking the tea experts in Liu Bao, or through studying the Records of Liu Bao. It was possibly due to the fact that Shen Chang Zhan formed a joint venture with another teahouse, and the business did not run under its own name in Liu Bao. Another tea expert suggested that Shen Chang Zhan set up a factory in Chen Cun, a town near Guangzhou, and Liu Bao teas were produced there and then exported to Southeast Asia countries.

In the late Qing Dynasty, Liu Bao tea was becoming more and more famous in Hong Kong, Macao and Southeast Asia. Surely, the demand of this tea was huge in these regions. According to Li Xuqiu, a tea expert who was already in his nineties, his grandmother told him that Hong Kong Tian Shun Xiang Teahouse, Guang Yuan Tai and other famous teahouses had already set up offices in Liu Bao during this period. Li told me that he could still remember that the name of each teahouse would be written on the pillar outside its building. He also confirmed that the logo of the teahouse would be drawn on each of the baskets used to transport teas.

At that time, Hong Kong Tian Shun Xiang and Guang Yuan Tai were two of the most famous and largest teahouses. Both of the teahouses had branches in Guangzhou and Hong Kong. Guang Yuan Tai even opened a branch in Ipoh, a city located in Southeast Asia. Guang Yuan Tai was established in the Qing Dynasty, during the Qianlong Emperor (1736 - 1795). The business originated in Quanzhou of Fujian Province. There is a colorful story about the establisher of this teahouse.

The father of Guang Yuan Tai's establisher was selected to be a government official through the imperial examination system. After working in the government for a few years, his career path was not smooth, and he finally resigned from his post. Afterwards, he ordered his offspring to be businessmen and not to walk the path that he walked. Obeying the order of his father, the man set up Guang Yuan Tai in Quanzhou. In 1757, after the export ports in Fujian were closed down by the Qing government, the teahouse was relocated to the Thirteen Hongs of Canton in Guangzhou. Since then, Guang Yuan Tai focused on the tea business. The business was welloperated, and in the late Qing Dynasty, the teahouse was already famous for its excellent product quality. Branches were opened in Hong Kong and in Southeast Asia. The Liu Bao teas produced by the teahouse sold very well, and the products were popular in Guangzhou, Hong Kong, Macao and other regions.

Later, the teahouse would classify its products into four grades, namely Saicha (細茶), Yuandu (元度 or 原度), Cucha (粗茶) and Xingdeng (行等). The teahouse also created a unique nei fei for its products. On the nei fei, there was a Chinese slogan printed to promote its products ("天 寶物華名茶世家省港聯號百年製 茶廣選精作元度細茶泰和順雅品 質尤嘉爰憑印鑑謹識無差毋致偽 假," which roughly means "A famous teahouse that operates in Guangzhou and Hong Kong, with more than 100 years of experience in tea-making, carefully producing precious products with excellent skills. The tea is great quality, and it has a mellow, smooth and elegant taste. Please distinguish between the real and fake products by looking at the company seal"). The name of the teahouse was also printed in the middle of the nei fei. In addition, each of the nei fei would also be sealed, so that the consumers could distinguish between the genuine and counterfeit products. The packaging was innovative, leading other teahouses to copy this idea.

In Liu Bao, Guang Yuan Tai set up a large office. It was known that Guang Yuan Tai was often willing to purchase teas at a price higher than others, and would always purchase large amounts. Due to its craft in the tea production process, Liu Bao teas produced by the teahouse was unique. As the teahouse described it, it had a "mellow, smooth and elegant taste," which attracted tea lovers in China and overseas.

The hot-selling Liu Bao tea undoubtedly improved the living conditions of the local tea growers. Official statistics suggest that a stellar amount of more than 700,000 catties (or 350,000 kilograms) of Liu Bao teas were sold in 1935, which is amazing for such a small area compared to other tea-growing regions of China. Li Xuqiu, an experienced tea expert, told me that as the tea traded by merchants and sole proprietors who did not establish an office were not counted by the government, the official statistics would tend to underestimate the actual volume of Liu Bao teas being produced and sold. He estimated that 800,000 catties (or 400,000 kilograms) of tea leaves were exported from Liu Bao during that year. As a comparison, Guangxi, as a whole, had exported 2,250,000 catties (or 1,125,000 kilograms) of tea leaves during this same period.

In 1931, the civil defense corps was organized by Li Zongren and Bai Chongxi, and many villagers in Guangxi joined the corps. The objective of the corps was to recruit members, ideally volunteers, and train them to be soldiers and commanders. They hoped that through organizing the corps, local defense forces could be set up, which was also a means to achieving political autonomy and, ideally, a self-sufficient economy.

In the summer of 1936, Shao Zhiqiang, the village head of Liu Bao, started to think about ways to take the money away from the tea growers who were becoming rich. As a result, he set up a military conscription policy in the town. Many teenagers in Liu Bao were then drafted to the civil defense corps through drawing lots, and those who were drafted could be exempted from military service by donating 1,000 or 2,000 kilograms of grain. In order to avoid serving in the corps, most of the villagers chose the option of donating grain. Many tea growers then became poor once again.

Even though most of the tea growers were not well educated, they were relatively well-informed, since they had been conducting business with Guangdong people in the cities for quite a long time. They knew that they were being treated unfairly, and they decided to organize a protest against the village head. Around 300 villagers gathered in Hekou, with Chen Xiongjie and Wei Jingping as the leaders. The village office was surrounded by the protesters the next night. Holding torches, the protesters were planning to break into the village office and catch Shao, the village head.

Many teachers and students were living in the village office, as the office building was also used as a school. Hiding his face behind a rice bucket, Shao successfully escaped from the village office, as the protesters thought he was a teacher or a student. Failing to see Shao after waiting for a long time, the protesters finally realized that he had already left. The angry protesters burned the village office with kerosene, and this incident has been called the "Village Office Fire" since then.

Li Xuqiu told me another story. In 1937, China was being invaded by Japan. Due to the lack of information flow, people failed to realize how bad the situation was. Two of the tea masters of Guang Yuan Tai, who were responsible for purchasing teas, were in Liu Bao at that time. In October 1938, Guangzhou fell to Japan, and it became impossible for ships to leave Xijiang.

Failing to communicate with their families and company, the two tea masters had no choice but to stay in Liu Bao. But they were not alone. Many tea masters from other teahouses were also forced to stay in Liu Bao, along with the large volume of teas that they purchased. During this period, they were often blackmailed by the local gangsters who were not only targeting their money, but also looking to rob them of their tea leaves. In 1945, the tea masters in Guang Yuan Tai left Liu Bao and sold the tea leaves that they had been keeping for seven years. Unexpectedly, these aged tea leaves sold extremely well in the market, and the market price for this batch of tea was four times higher than usual. This story, which was verified by several Liu Bao tea experts, shows that tea drinkers at that time had already realized that aged Liu Bao tea is better.

There was a legend among the tea growers in Liu Bao: On the mountaintop of Heishi Mountain, there was an old, old tea tree, which was called the "King of Tea Trees," as it was the ancestor of all other tea trees in Liu Bao. According to one legend, the Queen Mother of Heaven visited Earth with her fairies. During the trip, a heavenly seed was planted, which would grow into the King of Tea Trees in Liu Bao. Aside from this beautiful story, there was another legend related to the God of Tea, which is, perhaps, not as colorful as the previous one. It is said that the King of Tea Trees is the embodiment of the God of Tea, who has protected the well-being of people in Liu Bao since ancient times. And, of course, the fate of the town is also in the hands of the God of Tea. Liu Bao people believed that the tea leaves collected from this tree did not only have a unique flavor, but also had the power to cure any otherwise incurable diseases.

In the past, there was no such thing as a clinic or hospital in Liu Bao. People could only rely on prayer and the magical tea tree to cure their diseases. People from the tea town would sometimes leave their home to go to the Heishi Mountain late at night. After drinking the teas brewed by the leaves collected from the King of Tea Trees, many patients recovered. Such cases were wide-spread by word-of-mouth, and surely, the stories soon became more colorful than the facts. Whether it was a coincidence or the power of God was not really important, as the fact was that most of the elderly in Liu Bao believed that the King of Tea Trees was the embodiment of the God of Tea, who was responsible for managing everything related to teas on Earth. It was also believed that the God of Tea was protecting their welfare.

In the 1930s, a temple was built in Tongping, a town near the Heishi Mountain, to worship the God of Tea. Two rituals, during spring and autumn, were held every year to give thanks to the God of Tea. Deng Zhaoming, the then-village head of Liu Bao, confirmed that such a tree had actually existed, as he saw it himself. He said that the tree was located near the mountaintop, and it was growing from cracks in the rocks. According to Deng, the diameter of the tree was about 30 centimeters, and the location of the tree made it extremely difficult and dangerous to collect its leaves. People who climbed down the cliff to collect the leaves from this magical tree were tied with a rope.

Led by tea experts in Heishi Village, I visited the Heishi Mountain several times, attempting to search for the location where the King of Tea Trees was. One of the experts told me that the tree had been there since ancient times, growing strong stems from cracks in the rocks. Its leaves had a unique and great taste, and the leaves could be brewed for many times. It was believed that many of the tea trees grown around the region were the offspring of this tea tree. He added that the teas leaves collected from the King of Tea Trees were great, as Lu Yu, who was respected as the Sage of Tea, also suggested that good tea trees were grown in loose, rocky soil in the Tea Sutra.

I also interviewed Chen Zhendong, who was the manager of the tea export organization in Liu Bao. While he had never seen the King of Tea Trees himself, he recalled that many villagers would go to the Heishi Mountain to collect the leaves from the tree, regardless of how dangerous it was, as people deeply believed in the magical healing power of the tree.

In 1959, the period when the Great Leap Forward was happening, Chen was the secretary to the People's Commune in Liu Bao. During a committee meeting, Yi Xiecheng, one of the committee members, announced that he had already chopped down the old tea tree of the Heishi Mountain. Yi claimed that not only would the villagers go to collect the tea leaves on the cliff without considering their own safety, but they would also spread the superstition about how the tea leaves could cure diseases after they came back. He believed that in order to stop the superstitious villagers, and also to protect their well-being, he had no choice but to chop down the tree.

Many were possibly shocked and saddened, both by his actions and by the sudden death of the tea tree, though no one said anything about this incident, as it would possibly be considered as politically incorrect at that time. Except for those who attended the meeting, almost no one knew what happened. People would only realize later that the King of Tea Trees was "gone." Deng Zhaoming said that it would be extremely difficult, if possible, to chop the tree down. Still, Yi did it, and the tree was forever gone. Deng believed that if the 1,000-year-old tea tree was still living now, it would be heavily protected instead of being chopped down. However, "destroying superstition" and "protecting the public" were very strong reasons in 1959. What a pity!