|

|

The Ming Dynasty (1368 - 1644) was a time of great change for Chajin. As we will read later, the emperor banned the production of powdered tea cakes as an extravagance. Overtly, he did so for economic reasons, as the production of such tea costs more in terms of labor, and ultimately yields less tea. But many scholars say that the ban also had to do with his humble upbringing and a disregard for the pretentious arts of nobles and aristocrats, suggesting that he wanted others to drink the kind of tea his family would have had access to. Either way, these changes created a swirling tea world of bowls and cups, whisked and steeped tea that continued in combination for at least fifty years as people continued brewing the cakes they had, maybe secretly producing more, and meanwhile also started celebrating the new steeped tea with evolving brewing methods and new kinds of teaware, some of which continue today.

Many Western authors mislead the budding tea historian with the idea that tea was "boiled in the Tang Dynasty (618 - 907), whisked in the Song (960 - 1279) and steeped beginning in the Ming (1368 - 1644)." There is truth in this statement, but it is akin to saying "Americans wore bell-bottom jeans in the 1960s." The fact is that many Americans never wore bell-bottoms, though it was popular at that time amongst certain segments of the American population. In the same way, these brewing methods were trends. China has always been a vast empire, with many ethnicities, cultures and lifeways. These brewing methods were popular at those times among the aristocracy, who, of course, did most of the writing. Just as it is today around the globe, all throughout the amazing, massive empire of China, there were many ways to brew tea, from very simple, unprocessed leaves boiled in a medicine pot or steeped in a bowl to the very complicated rituals popularized by the scholars, artists and nobles of the Tang and Song dynasties.

The problem with using historical records to understand our past is that the rate of literacy goes down with each generation as you move back in time. Less than half the world was literate just a couple centuries ago. The result is that the perspective of historical records doesn't just narrow the further back you go, but worse, it narrows specifically along class lines, for it was only the wealthy who could read and write. This problem has led some tea scholars in the West to promote the idea that tea began in the Tang Dynasty with Lu Yu, even though Master Lu himself mentions much older books, some of them mentioning tea, and others devoted entirely to tea (though none still exist). Tea is very ancient. And though it did become popular amongst the mainstream of China in the early Tang Dynasty or thereabouts, it was used by many aboriginal tribes for thousands of years before that.

There is also a growing trend of tea lovers who want to intentionally ignore the fact that the commoditization and recreationalization of tea is rather modern, arguing that these ancient manuals were mundane how-to essays, which is simply not true. One of the biggest challenges we have faced in translating the Cha Jing, the emperor's Treatise on Tea and these Ming Dynasty works is that they are all written in a mystical prose that suggests all kinds of Buddhist, and more often Daoist philosophy, symbolism and poetry - all of which is very difficult to convey. No doubt, as more and more translations are brought to light, brushed by hands more skilled than ours, the essence of this old, beautiful language will be conveyed more clearly to English-speaking tea lovers. As with our previous works in this Classics of Tea series, we have tried our best to translate these works into a working, modern vernacular, mostly because that is easier to do.

Sadly, modern people ignore the wisdom and heritage of indigenous people, including our own ancestors, who were all indigenous - be it Asiatic, African, Germanic, Celtic or Native American, all of us come from indigenous, tribal peoples. Many scholars ignore the millennia of tea wisdom indigenous people cultivated, choosing instead to date tea's origin to its popularity in mainstream Han Chinese culture. To us, this is belittling of Tea.

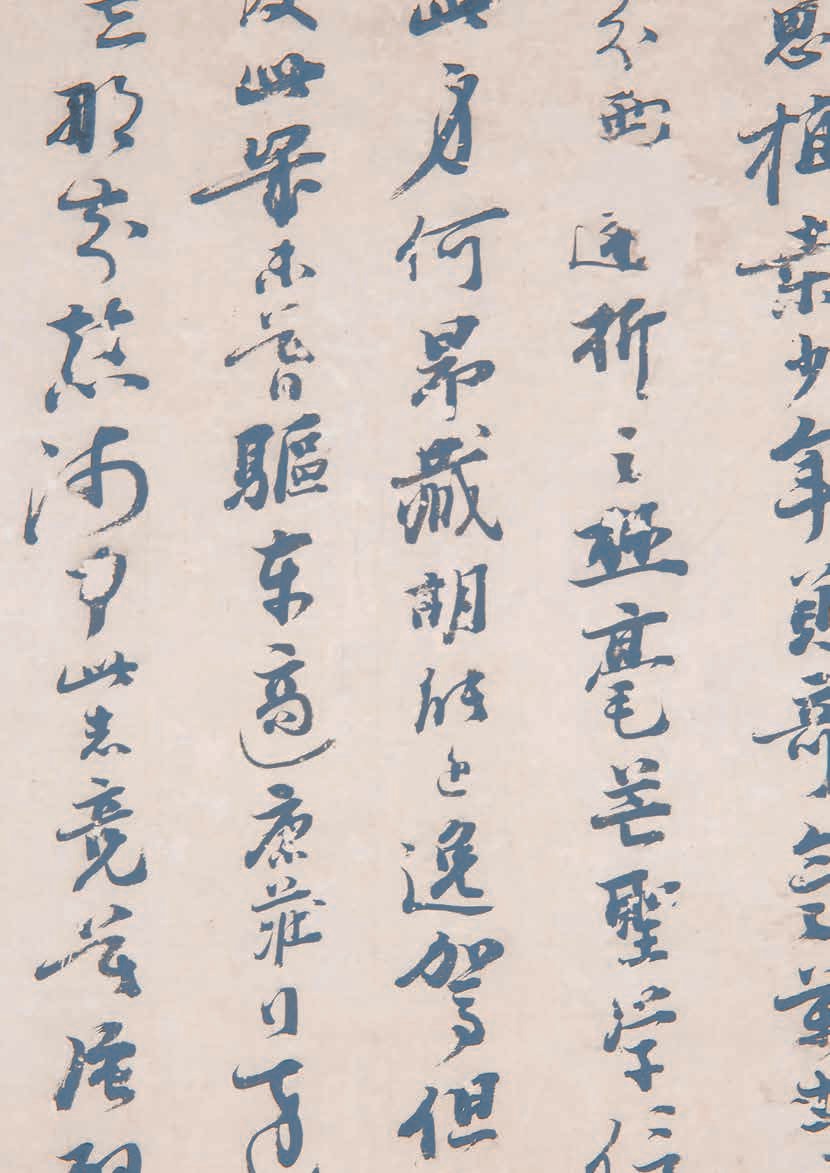

These classic works are very difficult to translate. Ancient people valued words much more than we do, for their power and grace, and therefore used them more sparingly. Carving on bamboo or stone, or brushing ink to paper all cost more to an author - in terms of time, energy and money. The old ones, therefore, left a lot unsaid. This, of course, wasn't just economically motivated. They wanted the reader to be left with mystery and gaps, spaces that point off the page like calligraphic twirls at the edges of Chinese characters. These old tea masters knew that most of Cha Dao is in the bowl, not on the page; and that the words could, at best, but point towards that spirit flowing from Nature into the Leaf, into us. Daoist sages are renowned for hiding their meanings so that only the earnest seeker who truly practiced and explored the work would find its essence. It's as if it was all written in the sloppy, "grass script" calligraphy - the kind even a Chinese scholar has difficulty reading.

In Kakuzo Okakura's amazing Book of Tea, he says that "Translation is always a treason, and as a Ming author observes, can at its best be only the reverse side of a brocade." Indeed, this translation is but the coarse underside of a glorious and intricately beaded brocade that depicts splendid scenes of Nature, water, fire and tea - and we can see but a faint and upside-down reflection of it by looking through.

We hope that these translations will add to a growing body of tea work in English, and inspire authors to try translating and commenting on these old works, so that we may better understand and appreciate the history and heritage of this Leaf we adore. In this issue, as with our previous translations in this series, we have taken a more literal approach to translation, while trying our best to preserve the essence of the original. However, any and all misleading information, mistakes or awkward phrasings are ours and ours alone. May these translations benefit tea lovers now and those to come!