|

|

Apart from a stray Marco Polo or so, very few Occidentals and Orientals had ever met face to face until Vasco da Gama of Portugal sailed around Africa's Cape of Good Hope and, guided by the Arab pilot Ahmad ibn Majid, reached India in 1498. It was almost twenty years after da Gama's voyage when, for the first time, a European vessel stood to off the coast of China. The ship was over fifteen thousand sea miles and almost two years' sail from its Portuguese home port. To return, her captain had to find his way through a maze of uncharted rocks, shoals and islands, cross the Indian Ocean, beat his way back around the Cape into the Atlantic, and then face a still-considerable voyage to Lisbon, all in a small, square-rigged ship that was hard to handle under the best of circumstances and absolutely helpless in a storm or against a headwind. Such voyages to China were to multiply with astonishing rapidity.

The appearance of the Portuguese, and later the Spanish, in Asian waters was of no great importance to the Ming authorities in China or their neighbors in Japan and elsewhere. The seas of East Asia were full of shipping, both merchant ships and the pirates who preyed on them. At home, the Ming government had restored order: cities revived, trade flourished, and silver became the national currency. China's fine arts, like her textiles, porcelain, and printing, had all attained a rare perfection and were avidly sought after. Europeans simply joined the busy commercial exchanges in this most prosperous part of the world. In return for her luxuries, China soon received from her new European customers the sweet potato and peanuts, but also more efficient firearms, missionaries and tobacco. She absorbed Spanish-American silver brought to Manila annually by a galleon from Acapulco.

Contact and commerce with Japan was officially restricted to the port of Ningbo; Fuzhou was designated the official port for the Philippines. The Portuguese carried on a sort of buccaneering trade up and down the Chinese coast for forty years until the Emperor finally granted them a legal port of entry and base of operations. This way he could collect the import-export duties he was missing otherwise and keep the "foreign devils" under the Ming thumb. The place selected was a rocky peninsula about three miles long that jutted off an island in the Pearl River Delta a good many miles downstream from the major port of Guangzhou (Canton). The Portuguese named the place Macao and received exclusive rights to trade there. China was to reclaim Macao in 1999. The poet W. H. Auden has written, "In 1557 a weed from Catholic Europe took root between the yellow mountain and the sea and grew on China imperceptibly."

Although introduced to China, Europe had yet to be introduced to tea. After the grant of Macao, it would take a little over fifty years before Amsterdam received Europe's first tiny shipment of tea, and a full century before tea could be bought in London. In China, meanwhile, tea kept steadily developing alongside the other arts and crafts. As the tea gods ordained, so it happened that the Ming Dynasty witnessed discoveries and innovations that radicalized tea processing and tea preparation alike. Loose leaf tea and the teapot for steeping it flourished in the Ming, destined to be ready and waiting for export to the other side of the planet.

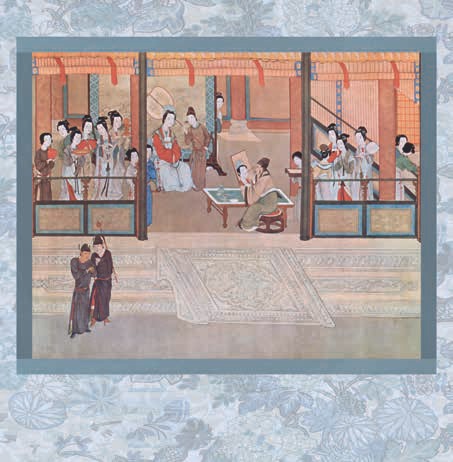

The first Ming Emperor Hongwu in 1391 decreed Tribute Tea need no longer be steamed and compressed into cakes. As loose leaf tea became the norm, tea masters produced pan-fired green tea and invented the first oolong tea, flower-scented tea and even red tea. To steep them, potters in Yixing began producing their legendary teapots. Scholars, tea lovers and potters worked together to achieve wares beautiful to hold as well as behold. Buddhist farmer monks were probably the most influential of all in tea development. Da Fang (1567 - 1672), abbot of a temple on Lao Zhu Ling Shan in Anhui, developed a tea still produced today. Monks from Songluo in Anhui took their skills with them to Mount Wuyi in Fujian and came up with oolong. The year 1541 saw publication of many great treatises on tea, like the Book of Tea, the Cha Pu (Tea Handbook) by Gu Yuanqing. He provides a description of teas of the time from manufacture to preparation and serving. These were the teas enjoyed during the Golden Age of prosperous 31/ Ming China Meets Renaissance Europe and powerful Ming China at its finest hour, the reign of Emperor Wanli (1573 - 1619), who "held the gorgeous East in fee" at the time those lost, hungry Portuguese seamen first hove to.

Portuguese royalty and rich monopolists learned to enjoy "cha," as it was called in Macao, before all the other Europeans learned to call it "tay" from the Dutch importers, who got the name from Fujian dialect-speaking traders. Dutch ships swarmed into Asian seas after 1600 and in 1610 brought back the first tea sold in Europe. Years later, "As tea begins to come into use by some of the people," observed the directors of the VOC or Dutch East India Company in 1637, "we expect some jars...with each ship." This first order for regular tea imports is a matter of historic importance. The West has imported Asian tea uninterruptedly since 1637 during the reign of Emperor Chongzhen (1627 - 1644), the last of the Ming to rule. Drinking the tea of the Ming was commonplace from Southeast Asia to Persia, while Europe was at first receiving tea only in tiny driblets, as little as thirty pounds in a six-month period, a luxury to set before William of Orange or a king or two and his noble friends. A century later around 1737, however, tea was to exceed in value all else the Dutch East India Company or the English East India Company would import. The Qing Dynasty had long since replaced the Ming by then, but it was tea as the Ming knew it that the Europeans imported and spread everywhere. As the tea gods had ordained, so it happened that the Ming radicalized tea production and preparation and so loose leaf tea and the teapot were ready and waiting in the homeland of tea to be carried around the world.