|

|

Wen Zhengming 文徵明 (1470 - 1559) was a famous artist in the late Ming Dynasty in Suzhou, which was a hot spot for literary figures. He came from a family of generations of officials and grew up with another popular literary figure, Tang Yin,1 who became a high-ranking official when he was 28. Wen had a bumpy journey pursuing officialdom, as he lacked the requisite talent for essay-writing. He made numerous attempts at sitting the official national examinations that were held every three years, and failed nine times! Despite his attempts, Wen failed to obtain an official title for several decades. He eventually obtained a petty title through connections when he was 53, only to resign 3 years later, finding the world of officialdom too hostile. Nevertheless, he was popular among high society and his calligraphy and paintings were very highly sought-after.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, officials often held literary gatherings where they would drink wine, compose poems, and sometimes even paint and write calligraphy together. Although visiting learned friends and drinking wine together had been a common activity for literary figures since the dawn of civilization, the booming economy and the increasing availability of public transportation since the 15th century in China made it easier for people to travel longer distances. As a result, high-end restaurants and taverns began to emerge all over China. In addition, many high officials and aristocrats in southern China built gardens stretching hundreds of acres to receive their friends and to avoid having to mingle with the common people. One of the most prestigious gardens in Suzhou, the Humble Administrator's Garden, owned by Wang Xianchen,2 was made famous by Wen Zhengming's writing and paintings. Apparently, Wen often stayed at the poshest gardens in Suzhou as their owners' honored guest. Wen was so prudent (and probably even intolerant of alcohol) that he refused to drink more than six cups of wine at any given party. So, he preferred to go to tea-drinking literary gatherings to avoid the pressure to imbibe. In one of his poems, he said "I do not drink wine, but I do get drunk on tea." Partly because he had never held an official title before the age of 53, he had much more free time than most other gentlemen to work on his art and tea-related research. He wrote a systematic commentary on an existing work, the Record of Tea by Cai Xiang (1012 - 1067),3 which was titled Commentary on the Record of Dragon Tea Cakes.4

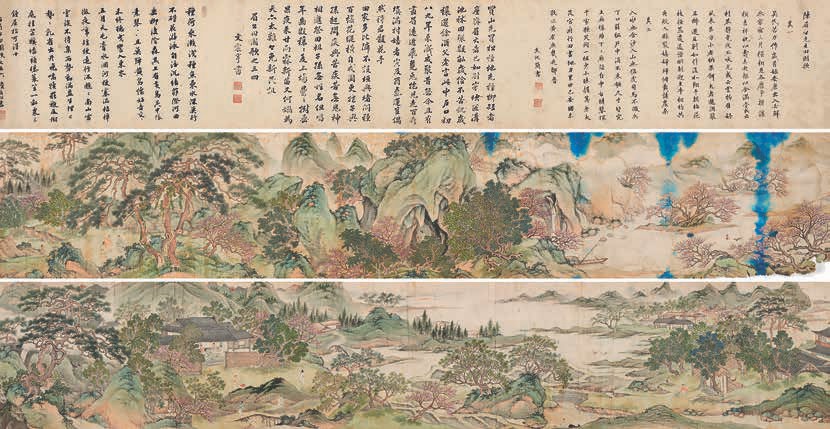

One of Wen Zhengming's works is a hand scroll depicting a trip to Mount Hui, a mountain whose water was renowned as the finest for brewing tea. In the year 1518, when Wen was 49 years old, he traveled to Mount Hui with several officials, including Wang Chong, Wang Shou,5 Cai Yu and three others. Wang Chong and Wang Shou were two brothers who often frequented the Humble Administrator's Garden, although they were of no immediate relation to the owner. Like Wen, Wang Chong had not had much luck forging a career as an official, and he also excelled in calligraphy. In fact, Wen Zhengming, Wang Chong and Zhu Yunming6 were the three most famous calligraphers in Suzhou during the 15th and 16th centuries. Wen Zhengming and Wang Chong had been planning to take a trip to Mount Hui to taste the famously pure and sweet spring water for years. Even though it was only 60 kilometers (40 miles) from Wen's home in Suzhou to Mt. Hui, it would have taken them weeks just to walk to the foothills surrounding the mountain. They arranged to visit Cai Yu's teacher, who lived near the mountain. The traveling party came prepared with their favorite tea and all the cauldrons, teapots and utensils they would need to savor the best brew of their lives. The hand scroll depicting this expedition begins with an inscription written by Cai Yu about the details of the trip: "On the day of the Qingming Festival, the seven of us stopped at a pavilion with two springs on the hills of Mt. Hui, and poured the spring water into Wang's cauldron. We made the thrice-boiled hot water and enjoyed the tea..."7 In the passage, "thrice-boiled" hot water refers to the proper boiling technique, where the water must be boiled until the bubbles roar and splash everywhere. This technique had been described in almost all articles on tea since the Tea Sutra by Lu Yu (733 - 804).

In Chinese hand scrolls, which are in a long horizontal format, there can be writing both before and after the painting section. Hand scrolls are so named because they are usually rolled up and stored away, and when they are occasionally taken out for viewing, they are unrolled and held in the hands to admire them. Hand scrolls are viewed from right to left, similar to the traditional Chinese writing system where the vertical lines of text are also read from right to left. Just as we now scroll up and down on computers, ancient Chinese "scrolled" right and left when they read calligraphy, letters and hand scrolls (flat-bound books appeared after the ninth century). In addition, most hand scrolls were kept in a box after being rolled up. It took time to open the box, take out the hand scroll, untie the silk string and then unroll the scroll itself. As a result, viewing a Chinese hand scroll painting is almost like an art installation in that a temporal element forms part of the viewing experience. A hanging scroll, on the other hand, is vertical and can be hung on the wall for public exhibition. As a rule of thumb, most Chinese hand scroll paintings are private, for personal use, while hanging scrolls are mostly for public viewing, even though they might not be hung all the time.

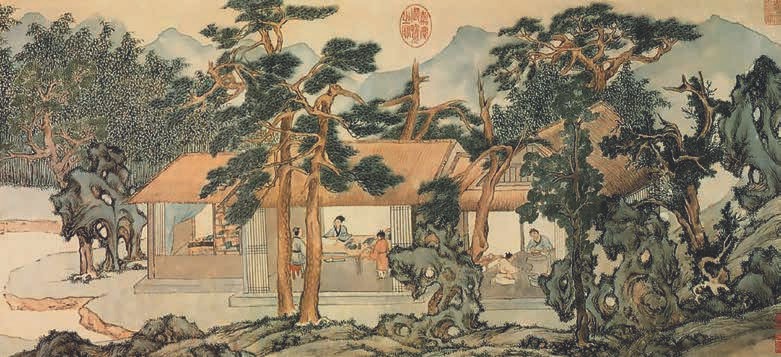

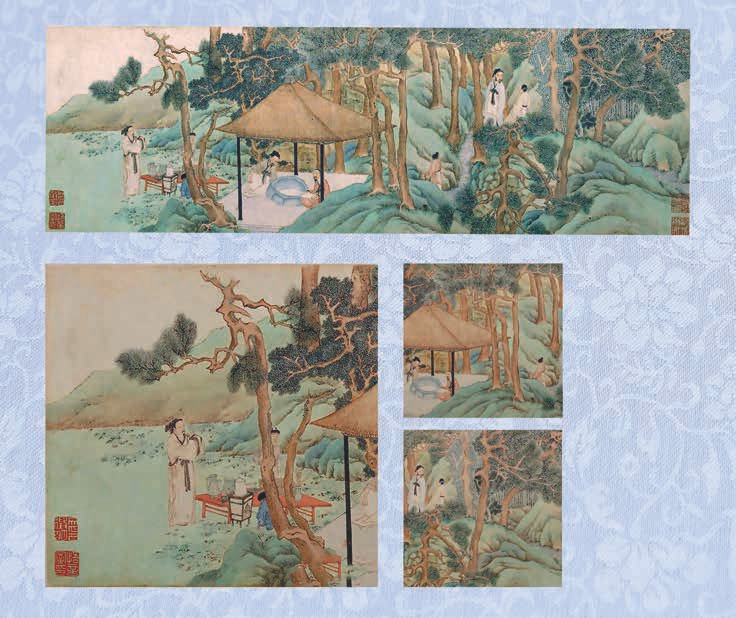

After Cai's written passage reports the factual information about the whole event, the painting is then revealed to the viewers bit by bit. We first see a big boulder at the very beginning, followed by a dense bamboo forest with several tall pine trees. Among the thick forest, two gentlemen are talking and enjoying nature. Then, two more gentlemen are sitting and chatting around a well, below a hut. To the left of the hut, two servants, mostly obscured by a pine tree, are brewing tea while another gentleman watches. In front of the crouching servant and the low orange table stands a type of portable stove, which was called a "gentleman of principle"8 at the time. It has a big teardrop-shaped opening in the front panel for coal and a water kettle on the top. There are several other objects such as water jars, a box (probably full of other smaller utensils) and several tea bowls on the table.

At this point, most modern viewers might be wondering why Wen did not portray all seven gentlemen who were on the trip, nor depict all the utensils needed for brewing tea. It may come as a surprise, then, that the ancient Chinese, especially literary figures, were not given to thinking so literally. In the eleventh century, a controversial but respected poet, essayist, painter and calligrapher, Su Shi,9 wrote a manifesto on scholarly painting, claiming that realism in paintings was over-rated, superficial and irrelevant. The only real reason for painting was to convey the painter's personal impression of the subject. In addition, he clarified that since scholars had spent decades maneuvering ink while writing poetry and calligraphy, without any colored pigments, monochrome ink alone was sufficient to convey the essence of their visions.

Shen Kuo, a statesman and contemporary of Su Shi, also made a similar yet much more specific comment. Shen Kuo was a genius - a spectacular Chinese mathematician, astronomer, physicist, meteorologist, civil engineer, hydraulic engineer, art critic, inventor, geologist, zoologist, botanist, archaeologist, pharmacologist, cartographer, agronomist, ethnographer, encyclopedist, general, diplomat, poet and musician.10 Shen thought that those who painted architecture faithfully, using rulers and accurate perspective, were artisans but not good painters. He believed that there were three different kinds of perspective in painting. A good painter will internalize the panorama and then transform the entire experience into an overall impression, which he then embodies in a coherent painting. Therefore, those who made structurally correct drawings of architecture to the point that even the mortise system under the roof was depicted faithfully might have excellent fine motor skills, but they could not be classified as good painters. Chinese literary figures who enjoyed painting were clearly conscious that they painted to express their sentiments, emotions and perceptions rather than to record what they saw with their physical eyes.

With this ideology in mind, we can now come back to view this painted hand scroll from the beginning again. The preface written by Cai Yu tells us clearly that this painting is about Wen and his friends' trip to Mt. Hui to enjoy the best spring water in China. This is the only clear piece of information in the hand scroll - the rest of the content can be understood as symbols or suggestions. All elements in the painting signify certain things that happened on their journey. For example, the boulder at the beginning of the painting signifies Mt. Hui, the gentlemen signify the group of seven friends, and the objects on the table signify all the necessary utensils for brewing tea. This is why the rock, trees, hut and people are not painted to scale: perspective was irrelevant in Chinese paintings where the subjects were intended as symbols, not realistic depictions. Not only was the number of gentlemen "incorrect," but all the gentlemen also look so generic that none of them are identifiable as any specific person. Since Cai wrote down the names of all seven men in the traveling party, there was no need to add any individual attributes in the painting. By the same token, Cai specified the purpose of the trip in his writing, so there was no point in displaying all the paraphernalia for tea making on that tiny table. Furthermore, since it takes time to unfold the scroll, the temporal element at the time of viewing lent a visceral quality to the narrative of the painting. At the end of the painting (toward the left end of the scroll), some of the participants wrote a series of poems on points of interest and how they felt about the trip in general. In addition to the original members of the party, some privileged viewers from later generations who lived decades or centuries afterwards could make comments, too. It was like a Medieval Chinese version of Facebook - friends, or friends of friends, could keep commenting on one "post!" Indeed, hand scrolls were like a form of social media for the officials who composed paintings and poems together at literary gatherings. After the parties had finished, the paintings could be shown to other friends who might be invited to continue adding more comments to the scrolls.

Years after the visit to Mt. Hui, Wen Zhengming composed a poem entitled Brewing Tea, reminiscing about the trip he took with the Wang brothers a decade prior. "I still remember the taste of spring water in Mt. Hui so dearly in my heart. So whenever I am free, I brew tea myself. Even when it is freezing cold after the snow, I sit on the meditation bench after dark, sipping tea. These moments remind me of Tao Gu,11 who once brewed tea with snow, out of poverty. I, however, would not mind being 'tea sick,' like the famous tea lover Lu Tong."12 Even though it was easier to travel in the 16th century than it had been before, traveling must still have been a big event in their lives for these scholars to keep talking about one trip for decades afterward.

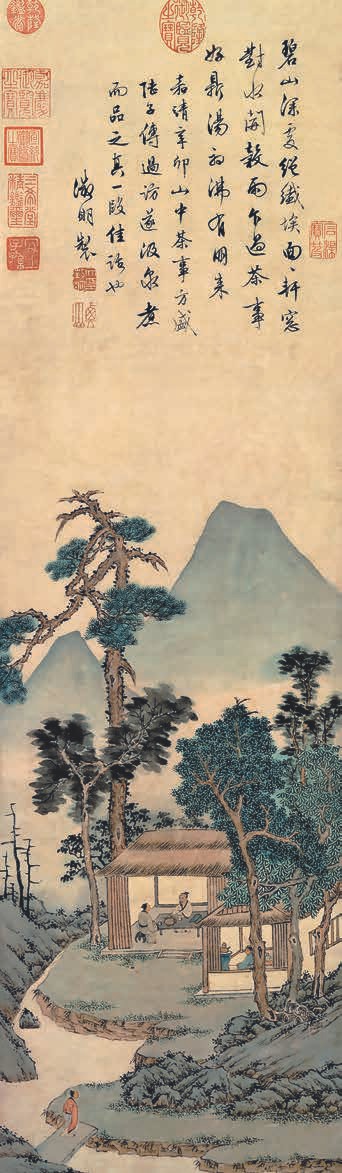

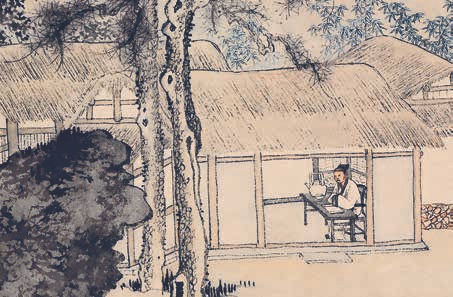

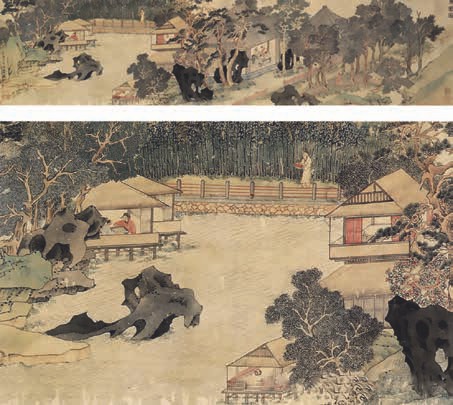

As much as Wen enjoyed tea, not many of Wen's paintings on the subject of tea survived. Years after he went to Mt. Hui, Wen finally obtained a position as a petty official, yet he had to resign only three years later due to constant bullying from younger and higher-ranking officials. About a decade later, when he was 61 years old, he painted a hanging scroll titled Tasting Tea. The inscription on the scroll reads: "The deepest forest on the jade-colored mountain is so clean and refreshing that it is devoid of even the most minute speck of dust. All the windows in the house face the beautiful waterfall. Right after the solar term guyu,13 tea business has good prospects. I just boiled my first cauldron of water and a friend came to visit me!"14 Then, he wrote "In the year 1531, tea farmers are busy in the mountains. Lu Shidao came to visit me, so I got some spring water and brewed some tea for us. What a lovely visit!"15 The painting is minimalistic to the point that it is almost devoid of any specificity. There are two huts under some trees. Two gentlemen are sitting inside of the bigger hut while a servant is brewing tea in the adjacent smaller hut. Again, the servant, who is almost blocked by the tree trunk, is tending the kettle on the stove. The layout of the tea huts is in accordance with Gao Lian's description in his Eight Notes on Healthy Living.16 Gao said that "the smaller hut for brewing tea should be built right next to the study. Inside the brewing room, there should be one tea stove... The young servant should only take care of this room, in case guests stay for the entire day or the master decides to stay up late during cold winter nights." In the lower left corner, above the stone bridge, another gentleman is arriving. The style of painting reflects Wen's personality: plain, without much embellishment, and straight to the point. No wonder Wen loved tea rather than wine: tea is such a cultured, acquired taste, whereas wine is much more imposing, pungent and overwhelming.

Three years later, when Wen was 64, (the same age that a young Paul McCartney sang of wondering if his darling would still love him by then!), he was so content with tea that he composed another painting on tea with a long inscription: Ten Odes of Tea Utensils (see cover of this issue). In the passage he tells how, due to an unfortunate aliment, he had to miss the yearly tea tastings at the neighboring tea farms. But then, he was blessed by his great friends who shared three new teas of the year with him. He was so exhilarated that he composed his ten poems in response to the existing Ten Odes of Tea Utensils by two famous ninth century poets and tea aficionados, Pi Rixiu and Lu Guimeng.17 The ten tea-related subjects are as follows: shallow valleys for planting tea, tea people,18 bamboo shoot tea, baskets for picking tea leaves, tea huts, tea stoves, roasting pits, tea cauldrons, tea bowls, and brewing tea. By now, I think viewers may not be too surprised to learn that this painting is virtually a direct copy of the one he did three years prior. It is true that Wen's tea hut was not likely to have changed much within three years, and it was certainly not unusual to copy one's own painting. Interestingly, ancient Chinese artists did not have a problem with employing other people's painting styles. The act of "copying" was considered an emulation of the other artist, as well as an exhibition of one's own penmanship. The more styles an artist mastered, and the wider his repertoire, the better an artist he was considered. In ancient China, the concept of plagiarism did not really apply to paintings. Of course, it would have been a huge scandal if one were to plagiarize any serious writing, such as to claim an entire political essay written by someone else as your own, or to hire someone to write your political examination essay for you. As early as the sixth century BCE, Confucius himself, arguably the most influential philosopher, educator, historian and statesman, told his students that he never said anything original - he merely retold what he had read before.19 For Chinese literary figures, embedding allusions in obscure ways is the art in all genres and forms. Again, this concept is very different from the modern concept of copyright - the belief that one must give proper credit to the original creator. It is not unlike the way things operated in Western classical music circles for several centuries (and even now): no one was criticized for performing music written by composers rather than by the player him or herself.20

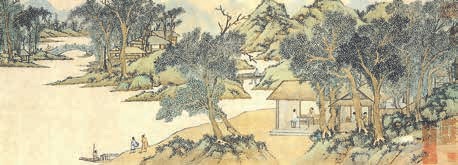

Two years later, Wen painted his Hu River Thatch-Roofed Hut for Shen Tianmin.21 In the inscription, Wen compliments Shen for being such a true gentleman. Even though Shen had already moved to the city, he still used the style name "Hu River" to remind himself where he was from. In the passage, Wen gives a short account of the history of Hu River, in which he traces the name back to the first century. He then pays homage to the villa, and to Shen, with a poem. Apparently, Shen was not from a well-respected family and did not hold any titles. So, Wen needed to do a little research about Shen's ancestry in order to compose the poem in a way that honored him. Even though the title of this painting is not directly related to tea per se, we can see the exact same twin huts at the beginning of the painting: a smaller one for brewing tea next to a bigger one where the master would receive his guests. To the left of the main hut, two gentlemen have just disembarked from a boat and are walking toward Shen's villa. This implies that Shen lived beside a lake with his own private dock. There are other houses scattered around the lake with bridges for easy access. In Wen's mind, the best attribute of a grandiose chateau was its simple thatch-roofed hut where unlimited fine tea was served upon request. That is why Wen did not paint a grand estate, even though this scroll was meant to be a flattering painting of Shen's mansion. Instead, Wen chose to paint two simple huts in one quarter of the scroll to exemplify Shen's loftiness and humble nature and elaborate the spectacular, almost fantastical environment in the remaining three-quarters of the painting. In this way, Shen's wealth was alluded to by the stunningly beautiful lake and the impeccable location of his abode. This pattern, with some minor variations, can also be seen in two of Wen's other paintings. East Garden22 was painted when Wen was 57 years old, shortly after he quit his petty official post, while The True Connoisseur's Studio was painted for his friend Hua Xia,23 an influential connoisseur and antique collector, when Wen was 87 years old. Even though these three paintings are in hand scroll format, they might well have been hung on the wall for display, especially the one of Shen Tianmin's estate.

Since the illiterate first emperor of the Ming Dynasty issued a decree to abolish sumptuous pressed tea cakes in 1391, loose leaf tea became ever more popular, and the gap between the elite and the common people started to diminish. In the 15th century, with the rise of the merchant class, the ease of long-distance travel and the popularization of mass-produced printed materials, news traveled faster, demand for tea increased and people could easily travel to tea plantations to taste famous teas for themselves. Lu Yu pointed out in his Classic of Tea that tea grows naturally in the south. So southern Chinese had already enjoyed the privilege of drinking fine teas for over a millennium. In addition, the fertile land of the south provided local people with a huge variety of seafood, vegetables and fruits. Hence, it is not surprising that the southern Chinese literati had a long tradition of luxurious and leisurely lifestyles. Among the rich and famous, simply showing off one's wealth was not viewed favorably - so some aristocrats and tycoons would befriend officials and literary figures, in the hope that some of their culture and elegance would "rub off." Wen's paintings and writings on the subject of tea, whether depicting his travels to Mt. Hui with friends in search of the perfect spring water, drinking tea with his student at his own house, tasting the newest teas of the year while he was ill, or painting tea huts as a gift in return for long stays in splendid villas on vast estates, provide us with a fascinating window into 16th century tea culture in Chinese high society.

"正德十三年二月十九,是 日清明,衡山偕九逵,履約,履吉,潘和甫,湯 子重及其徒子朋游惠山,舉王氏鼎立二泉 亭下,七人者環亭坐,注泉于鼎,三沸而三 啜之..."

"碧 山深處絕纖埃,面面軒窗對水開。穀雨 乍過茶事好,鼎湯初沸有朋來."